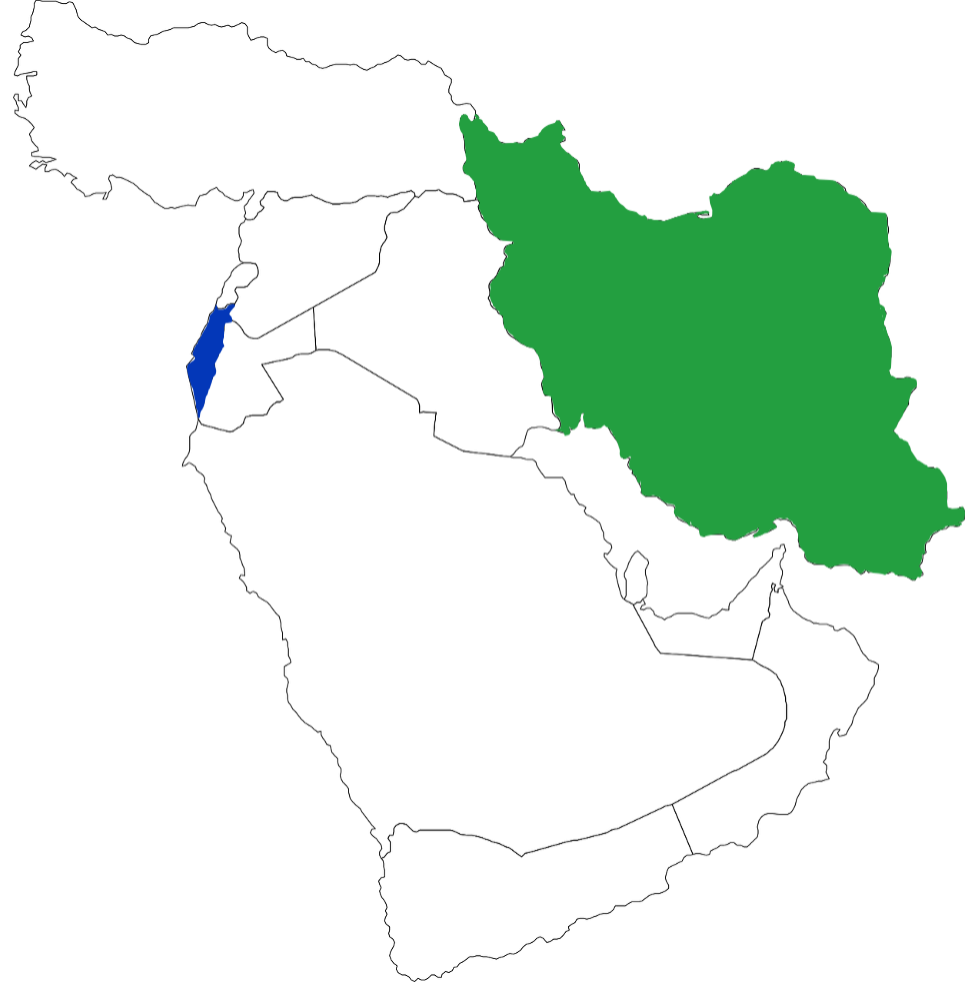

Reported Iranian intrusions against Israeli critical infrastructure networks and alleged Israeli actions against Iranian proliferation-associated targets pose substantial new challenges to understanding ongoing competition and conflict in the Middle East. These cyber exchanges may be interpreted through two distinct lenses: as the struggle to achieve deterrence using the instrument of cyber operations, or as the contest for initiative in order to establish conditions for relative security advantage in a cyber-persistent environment. Either way, these ongoing incidents are best understood not as “bolt out of the blue” attacks, but rather fleeting glimpses of continuing cyber campaigns leveraging previously disclosed and newly developed capabilities as each side grapples to anticipate cyber vulnerability and shape the conditions of exploitation. The opaque nature of these interactions is further complicated by potential bureaucratic politics and interservice rivalries, as well as unknown dynamics of a counter-proliferation campaign to slow, disrupt and potentially destroy Iranian nuclear capacity. In the end, observed cyber actions may not represent reflections of accurate strategic calculation, and even if aligned to the operational environment they may not lead to intended outcomes. Continuous failure to deter, or inability to manage persistent interactions, may lead to greater dangers.

Table of contents

Iran and Israel are allegedly engaged in cyber operations against each other. 1 Two key questions emerge. The core question is whether these operations have a deliberately pursued end state that reasonably follows from their actions. The secondary question is: if pursued, can this end state be achieved? There are two prominent end states that might explain these cyber interactions: 1. Each side is attempting to establish and re-establish credible deterrent red lines to persuade the other side to cease and desist; 2. Each side is trying to gain initiative within and through cyberspace to establish the conditions for relative security advantage—to gain some modicum of control in a fluid environment of cyber persistence. The analysis presented in this issue brief suggests that efforts to establish red lines are likely to fail and potentially lead to a spiral escalation. Gaining initiative through cyber operations for security advantage is a relatively uncharted form of militarized competition that could stabilize, but if handled poorly, also escalate a conflict.

Iran and Israel are allegedly engaged in cyber operations against each other. 1 Two key questions emerge. The core question is whether these operations have a deliberately pursued end state that reasonably follows from their actions. The secondary question is: if pursued, can this end state be achieved? There are two prominent end states that might explain these cyber interactions: 1. Each side is attempting to establish and re-establish credible deterrent red lines to persuade the other side to cease and desist; 2. Each side is trying to gain initiative within and through cyberspace to establish the conditions for relative security advantage—to gain some modicum of control in a fluid environment of cyber persistence. The analysis presented in this issue brief suggests that efforts to establish red lines are likely to fail and potentially lead to a spiral escalation. Gaining initiative through cyber operations for security advantage is a relatively uncharted form of militarized competition that could stabilize, but if handled poorly, also escalate a conflict.

Gaining initiative through cyber operations for security advantage is a relatively uncharted form of militarized competition that could stabilize, but if handled poorly, also escalate a conflict.”

At a macro level, these cyber interactions sit within the larger statecraft conducted by both countries as regional rivals. It is not clear, however, that what we are glimpsing is the simple introduction of an additional means (cyber) to that statecraft. It is important to consider how the operational interplay in, from, and through cyberspace may take a life unto itself. Importantly, this issue brief introduces the analytical lens that suggests that there is strategic value in contesting each other in cyberspace that itself becomes a new form of and context for competing statecraft. Cyberspace may be vital enough that what Israel and Iran are engaged in is advancing their broad rivalry with cyber means, while simultaneously contesting “control” over this vital new terrain itself. Thus, there are both new means and new ends driving behavior.

Alleged disruptive cyber attack at Bandar Abbas

In early May 2020, networks supporting shipping and cargo handling operations within the Iranian port of Shahid Rajaei at Bandar Abbas allegedly suffered disruptions following a cyber intrusion. 2 No technical reporting regarding the incident has been disclosed to date. The state-owned Rajaei facility has remained one of the country’s key logistics hubs, handling over 85 percent of Iranian import-export cargos. 3 Although downplayed by the Iranian Ports and Maritime Organization, satellite imagery showed continued disruption suggesting extensive delays at the container terminals’ eight vehicle entry and exit lanes. 4

The port of Shahid Rajaei handles over 85% of Iranian import-export cargos.

In early May 2020, networks supporting shipping and cargo handling operations within the Iranian port of Shahid Rajaei at Bandar Abbas allegedly suffered disruptions following a cyber intrusion. Although downplayed by the Iranian Ports and Maritime Organization, satellite imagery showed continued disruption suggesting extensive delays at the container terminals’ eight vehicle entry and exit lanes.

https://www.seanews.com.tr/iran-plans-to-bring-its-shahid-rajaee-port-to-state-of-art-status/183880/

Western and Israeli media reporting has linked this incident to offensive action by the government of Israel, allegedly in direct response to an attempted Iranian intrusion in late April 2020 against multiple Israeli water utility networks. These alleged Iranian attacks sought to alter industrial control systems in a manner that may have been intended to create lethal effects. 5 The alleged water treatment attack could also have been operational preparation of the environment for action timed as part of annual campaigns associated with Qods Day. While this date typically sees attempted intrusions and disruptive attacks from multiple ideologically motivated actors, in prior years these attempts have usually had only limited or merely symbolic impact. 6 This year’s effort likely assumed greater importance due to multiple pressures on the Iranian regime, including effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and earlier inconclusive regional conflict events—like the targeted killing of Qassem Soleimani—in which the Islamic Republic’s cyber forces were unable to effectively deliver operational results. 7 Commercial intelligence services noted indications of substantial efforts toward multiple intrusions—including intention to target Israeli national telecommunications infrastructure, missile defense warning systems and Iron Dome interceptors, and maritime navigation networks. 8

While full details of the Israeli response are not clear, the strike on the port may be considered:

an offensive cyber effects operation with a counter-value targeting objective or

an operational-level countering effort intended to unbalance, deny, or degrade Iranian intrusion capabilities 9

It is significant that public reporting on the port attack emerged less than a day after the incident was discussed in a meeting of Israel’s Ministerial Committee on National Security Affairs. 10Whether the security cabinet intended to overtly acknowledge this operation or not, its utility as a means of communicating with Iranian leadership was reinforced by subsequent statements by senior Israeli intelligence and cyber leadership.

Deterrence lens

Deterrence works by shifting an opponent’s mindset, through cost-benefit calculation, to convince them to not do something you have told them not to do. Deterrence requires several basic elements to succeed: 1. Your opponent must know what action is to be avoided; 2. Your opponent must calculate that the costs involved in taking the proscribed action credibly outweigh the benefits of inaction. The credibility of these costs rests on the opponent’s conviction that you have capability to inflict those costs and a willingness to do so.

Is deterrence of cyberattacks the end state being sought through these Iranian-Israeli interactions? First consider Israel’s purported action through a deterrence lens:

It should be assumed Israeli targeting of the port was based on prior operational planning—sophisticated cyber operations require significant preparation. Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines (IRISL) and other regime-controlled shell companies operating in the port have been at the center of ongoing ballistic missile and nuclear proliferation activities. Involved organizations and their leadership have previously been targeted as part of economic sanctions for nearly a decade. 11 As a result, it is almost certain that earlier intelligence and reconnaissance actions could have provided insights to enable new disruptive cyber effects.

Viewed through a deterrence lens, targeting the port could be intended to produce a demonstrative effect, showing the capability to hold similar targets at risk, that signals to adversary leadership (and its population) that if Iran continues to engage in cyber operations, Israel will respond with costly retaliation. Given how difficult it can be to judge the effect and severity of a cyber-attack, some have argued their demonstration is necessary to convince target audiences of the gravity of the deterrent threat. 12 Jason Healey has termed such demonstrative offensive employment a “loud shout,” distinguished from more subtle signaling mechanisms. 13 Some have argued use of an offensive capability tips the attacker’s hand, allowing the defender to react, fix the revealed vulnerabilities, and design around the imposition of future costs from the same capability. 14 For this reason, it has long been considered difficult to deter through the brandishing of offensive cyber options. 15 Even where offensive cyber options are employed as a “loud shout,” adversaries may not receive the message that planners might have intended, believing their knowledge of the attack prepares them to neutralize its use in the future. 16

It is possible that action against the Bandar Abbas port facility presented a unique opportunity for demonstrative attack without disclosing an exquisite (highly effective and hard to reproduce) capability unknown to the adversary. At least one prior campaign was reportedly conducted between spring 2010 and fall 2012 to degrade proliferation-related targets, likely including Iranian shipping operations. 17 A destructive malware variant was also observed in connection with attacks on multiple oil terminal facilities during the same 2010-2012 period. While eventually detected by Iranian defenders and attributed by foreign researchers to then ongoing Duqu and Flame campaigns allegedly conducted by Israel against Iran, the operation was never acknowledged and substantial unknowns about the incidents still persist. 18 Despite these unknowns, the precedent of earlier actions meant that while specific instances of given vulnerabilities that offered continuing options for disruption of the port networks might be highlighted in the new operation, the class of offensive capabilities employed were already understood by the adversary and therefore did not risk other more novel options.

Such action would further be consistent with the Israeli services’ thinking regarding proportionate response options as articulated around kinetic actions. In these cases, strikes intended to have deterrent value as part of efforts to sustain regional stability are delivered against targets previously identified through intelligence, and serve specific strategic objectives in addition to their signaling value. 19 This rationale underlies arguments that recent cyber operations were intended as retaliatory actions—demonstrating that any attacks on Israeli networks would be met by proportionate actions against the aggressor. 20

However, it is not clear that an Israeli cyber operation against the port was necessary for deterrence. Does Iran really doubt that causing Israeli deaths would lead to Israeli retaliatory action? If so (and thus precipitated a cyber operation), disrupting port services is quite an indirect way to draw such a red line and it is certainly not proportional to the loss of life that could have followed a successful Iranian attack on the water treatment facility. Since it was not proportional, in fact taking such action might create the opposite outcome–deterrence credibility would be undermined in the eyes of the Iranians who would see the Israelis responding mildly to their action. The salient deterrent point is that past Israeli kinetic action has likely established the red line against killing Israelis and has established credibility around both the Israeli capability and will to inflict costs. It is unclear if Iranian calculations view kinetic exchange or conventional war as cost prohibitive. If they do not then deterrence has failed, and cyber operations at this level are unlikely to reestablish it.

Cyber persistence lens

An alternative explanation is that Israel and Iran understand that cyberspace itself has an interconnected structure that creates a distinct strategic environment. Rather than security ultimately resting on the absence of some proscribed action (deterrent threat), each recognizes that security, in a highly fluid environment of constant contact, flows from being able to sustain initiative in anticipating and exploiting vulnerabilities inherent in networked computing (and the systems and interfaces that constitute the network). Thus, the non-acknowledged public glimpse into cyber operations between the two states reveals a competition through a continuous set of cyber operations across multiple campaigns that amounts to a grappling over who can more effectively anticipate the other. When effective defensively, vulnerabilities are not exploited as the actual conditions of each other’s insecurity are set and reset. Security requires persistence in cyber operations and perhaps Israel and Iran are learning this through a set of managed cyber interactions.

The Iranian attributed intrusion against Israeli water sector targets was not a “bolt out of the blue” attack, but rather part of recurring hostile competition over security. The incident is linked to ongoing campaigns and related capabilities development since at least late 2017. Initial access likely developed from Iranian and Iranian proxy efforts to target electric power distribution networks in Israel which have been ongoing since at least early 2016. Earlier phases of this cyber campaign were detected and publicly disclosed as ELECTRIC POWDER, leading the adversary to shift to new intrusions using modified tooling and new infrastructure. Fresh intrusions were observed in spring 2019, including apparent compromise of a technology start-up firm providing automation device management solutions for Israeli utilities. 21 While these intrusions do not appear to have resulted in the same potential for disruption in the energy sector, they may have provided insight supporting later action against water sector targets in Israel.

Iranian targeting of the water sector was likely further informed by planners’ awareness of an entirely separate incident in Ukraine. Here, a Russian origin intrusion was detected by Ukrainian security services after compromising the network at a water treatment facility near Dnipropetrovsk – prompting a public warning widely discussed within the information security community. 22This incident was almost certainly tracked by an Iranian offensive cyber acquisition program, ongoing since at least 2014, that seeks to identify new capabilities and mimic them through reverse engineering and/or parallel re-development. 23 This parallel development program is conceptually similar to Russian and other Western programs, and likely later evolved based on public disclosures around capture and replay acquisition techniques. 24 Subsequently, intrusions against water sector targets in the Gulf region, attributed to an Iranian-linked activity group—commonly known as APT34, HELIX KITTEN, COBALT GYPSY, or OILRIG—were observed in November 2018. 25 Critically, APT34 capabilities would be degraded in spring and early summer 2019 following a series of third-party leaks from a hacktivist group that exposed the activity group’s tools and active intrusions. 26 While APT34 and other associated activity groups responded by retooling and rebuilding supporting infrastructure, the higher profile of the operations and loss of deniability (however implausible), likely led to emphasis on other capabilities for planned action against the Israeli targets.

The alternative capabilities leveraged by successor campaigns to ELECTRIC POWDER were also less technically mature, having originally been aimed to imitate, and thus be confused with, a previously identified Palestinian origin threat activity group known as Molerats or EXTREME JACKAL. 27 EXTREME JACKAL has reportedly operated from the Gaza area since at least 2012 and was well known to Israeli intelligence. 28 EXTREME JACKAL hackers had previously been targeted in Israeli response actions that included kinetic airstrikes in 2019 against the group’s HAMAS-linked facilities. 29 Iranian operators are known to have previously leveraged hacktivist personas as a means of muddling attribution since at least 2009, and pursuing operations under a similar front would be consistent with this history. While commercial cyber intelligence services have not definitively confirmed the link, threats issued via social media from the “Jerusalem Electronic Army” (JEA) in April 2020, as response to Israeli computer emergency response team (CERT) warnings regarding water sector operations, may have been intended to continue this deception. 30 These threats included a claim to have compromised energy sector networks consistent with prior ELECTRIC POWDER targeting. 31

The JEA-front persona would also claim to have successfully compromised military surveillance systems and other targets associated with Israeli “settlements” in May and June 2020, providing imagery as purported proof. Jerusalem Electronic Army, “Penetration of an Israeli military surveillance 32 A second affiliated hacktivist group persona would subsequently claim further actions against industrial control systems targets in specific kibbutz communities in June 2020—implicitly crediting these intrusions to the HAMAS military wing, Izz Al-Din Al-Qassam Brigades, in a likely attempt to support the theme of widespread resistance. 33 Additional, as yet technically unattributed cyber attacks would reportedly compromise Israeli agricultural water systems in mid-July 2020. 34 These attacks would be claimed by the JEA attribution front as part of what it suggests are ongoing operations. 35 Concurrently, the JEA would also claim to have suffered degradation of its infrastructure by Israeli counter-cyber operations. 36 None of these cyber operations should be fully understood outside the context of ongoing campaigns to anticipate each other’s exploitation of vulnerabilities; they are all part of continuing competition between Iran and Israel.

So, from a cyber persistence perspective what should analysts make of the specific purported Israeli action against Shahid Rajaei port at Bandar Abbas? Here what appears tactically to be an offensive action may from an operational and campaign level be better understood as unbalancing an opponent, opening a different vector for Iran to defend, thus shifting the initiative back to Israel as Iran must be on guard for exploitation of vulnerabilities it had not effectively anticipated. Rather than sending signals in the hope of deterrence, Israel is actively resetting relative security and insecurity in and through cyberspace.

Implications and outlook: Double vision, through both lenses

The empirical record, despite its opaque nature, suggests that Iran and Israel are engaged in cyber operations of a continuous nature. This could be resulting from the failure of both sides to set sufficiently credible deterrent threats and, despite this failure, both sides are struggling to find a specific deterrent line each can hold. If so, this is a dangerous period as the nature of cyberspace suggests this attack-retaliate model of deterrence will likely lead to ever-increasing exchanges in which each side expects its escalation in intensity to finally adjust the thinking of the other side. Without mutual loss clearly understood by each party, such continued escalation may lead to a cyber operation that spurs a cross-domain kinetic exchange or, worse, war.

The empirical record might be understood differently. Both states might understand that they need to continuously grapple in cyberspace to anticipate what the other side might seek to exploit. Rather than trying to lock in inaction (cease and desist), the objective is to sustain relative security through initiative that allows one to establish conditions for security for themselves and insecurity for the other side. Without the roadmap of experience, these interactions could also lead to error, and a level of conflict that neither side is actually seeking.

However, if both sides desire to manage the challenge of cyber persistence, a more hopeful interpretation is possible. Then, these operations would align with the strategic realities of cyberspace and leave open the possibility for learning through action. Israel and Iran may, through their continuous cyber operations, become adept at understanding operations that have value short of war (produce relative security in reducing cyber exploitation) as opposed to those risking dangerous cross-domain action (if understood as conventional war).

Further distorted vision

The above analysis rests on the assumption that the observed behavior between Iran and Israel is driven through strategic calculation—that the two states are assessing their national interests, the strategic environment of cyberspace, and aligning their operations to achieve a better cyber strategic outcome, along with advancing their interests within their broader regional rivalry statecraft. Two alternative possibilities must also be acknowledged which further distorts the explanation of what we are seeing.

First, it is possible that the Iranian incursion into water treatment facilities is a result not of deterrence or cyber initiative, but bureaucratic politics. Iranian reliance on the ELECTRIC POWDER activity group at the forefront of the Qods Day thrust may have emerged as a result of internal service rivalries. Following setbacks to other Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) and Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS) capabilities, planners possibly sought to employ what they believed to be undetected capabilities in a “spectacular” event. This event was likely timed to coincide with other propaganda activities—including what may have been intended as new ballistic missile testing at the culmination of ongoing naval exercises—a highly desirable comparative milestone for a previously under-regarded offensive program. The alleged “joint” nature of the Jerusalem Electronic Army front—purported to be cooperating with the Syrian Electronic Army, and multiple other entities including acknowledged Iranian nationalist hackers—likely also reinforces these dynamics. The IRGC has reportedly invested heavily in training Palestinian, Syrian, and Lebanese hackers for many years. 37 This operation would likely have demonstrated return on these investments. As it turned out however, both naval and cyber engagements resulted in disaster for the Islamic Republic. 38 So it is possible that domestic pressures reflected through bureaucratic competition to please central leaders might have led to a riskier, more adventurist, cyber operation.

The alleged Israeli cyber strike on the port facility might have had little to do with cyber deterrence or persistence, but rather been part of a larger effort to undermine Iran’s nuclear proliferation.”

Alternatively, the alleged Israeli cyber strike on the port facility might have had little to do with cyber deterrence or persistence, but rather been part of a larger effort to undermine Iran’s nuclear proliferation. It is possible that Israel is using cyber means in a counter-proliferation campaign to slow, disrupt, and potentially destroy Iranian nuclear capacity. The broad nature of disruption caused by reported action against the Bandar Abbas network is not as clearly consistent with this objective. However, subsequent additional kinetic disruption was reported at multiple facilities in Iran in late June and early July 2020, including explosions at the Shahid Bakeri Industrial Group ballistic missile manufacturing facility, and most critically the Natanz Pilot Fuel Enrichment Facility centrifuge assembly hall. There are few details on these events at present and the Iranian government has been less than forthcoming, no doubt in part to conceal both the existence of the illicit programs at these locations as well as the degree of damage inflicted upon the regime’s aspirations. However, unconfirmed allegations—including reported statements by Iranian government officials—have surfaced suggesting offensive cyber operations may have played a role in these incidents. 39 Other regional intelligence sources point toward more classic sabotage scenarios, including covert emplacement of explosives at the target facility through insider access. Israeli officials have avoided addressing questions of involvement. 40 Yet commercial overhead imagery has identified specific features of the explosion that may indicate an apparent locus of damage traced along a specific gas delivery pipeline leading into the facility—in some scenarios potentially consistent with cyber-enabled effects, although analysis remains deeply inconclusive. 41

Additional incidents, including an industrial chlorine leak at the Karun petrochemical plant in Mahshahr, have also raised tensions; without any evidence to yet link these events. 42 Despite this, industrial failures in key Iranian infrastructure remain under intense scrutiny where they appear potentially consistent with previously disclosed contingency planning for large-scale counter-proliferation focused cyber operations, allegedly abandoned in favour of the negotiations process that resulted in the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). The prospect of such a campaign continues to loom large in Iranian official thinking. 43 With the failure of JCPOA, cyber options to deny and degrade Iranian progress toward an operational nuclear warhead and associated delivery capability presumably remain on the table—alongside other measures short of full-scale conventional military strikes. 44 However, it is far from clear that any specific counter-proliferation focused covert action that may, or may not, be ongoing is linked to continuing contests over control of networks for more conventional objectives. It is difficult to isolate threads of strategic thrust within opaque exchanges between antagonists acting in and through cyberspace. Inappropriately conflating separate campaigns including those pursued by differing actors, using different mechanisms of action and effect, and toward different national interests—remains a substantial challenge to accurately evaluating key components of state interactions in cyberspace. While it can be assumed cyber operations sit within the context of broader statecraft, we may be missing the full picture by assuming they are simply additional means to that statecraft, rather than seeing them as evidence of a contest over a new strategic domain itself with its own dynamics and ends in play—cyber statecraft in action.

Clearer vision

For those focused on cyber operations and the potential for strategic cyber-enabled campaigns, what can be generalized about the cyber interactions between Israel and Iran requires more scrutiny, but some basic analytical principles seem important to adopt:

Observers should not assume that the actions seen are necessarily reflections of accurate strategic calculation. It is possible that both states think they can deter despite all evidence to the contrary and thus the prospect exists that continuous failure to deter will lead to greater danger;

Observers should not assume that the actions seen are working even if aligned to the operational environment. It is possible that both sides are engaged in trying to manage an operational environment that rewards persistence, but given the lack of sophisticated experience this may lead not to relative security but the greater danger of relative insecurity;

Observers should not assume that the narratives that build up around specific cyber operations (and sometimes allowed intentionally to propagate by the actors themselves) are necessarily reflective of an episodic operation. It is possible that the operation itself is not what it seems to be. It is possible that it is a false narrative or, alternatively, not an isolated act at all but rather a part of a much larger campaign of which we are catching only a fleeting glimpse.

The unsatisfactory conclusion, thus, is that cyber security studies, analysts, and policymakers alike must work hard to perfect the lens through which greater clarity concerning cyber operations, campaigns, competition, and conflict will be obtained. This goal, at times, (such as in this analysis) may be forwarded by raising more questions than delivering answers, but such is the nature of the challenge faced in understanding where cyberspace fits in the relations of states.

Understanding these three analytical points moving forward is important as it should be assumed that cyber interactions between Iran and Israel will continue within the larger context of their regional hostility. How policymakers, planners, and operators understand specific actions and intended objectives therefore becomes increasingly vital as each side continues to grapple with the new dimensions of cyber operations as mechanisms of competition and conflict. Longstanding conceptual frameworks have offered great utility over the decades in helping to provide insight into these behaviors, but where unique features of the new domain may change the underlying determinants of key interactions it becomes critical to pursue new lenses that may offer greater clarity. Such clarity is much needed where the potential errors of observation, interpretation, and action may risk wider crisis. Therefore, one would hope that, minimally, allies of Israel are creating opportunities to learn from these operations to enhance thinking in both directions.

About the authors

* JD Work serves as the Bren Chair for Cyber Conflict and Security at Marine Corps University, and as a non-resident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative. He holds additional affiliations with the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University, the Elliot School of International Affairs at George Washington University, and as a senior adviser to the Cyberspace Solarium Commission. He can be found on Twitter @HostileSpectrum.

Dr. Richard J. Harknett is Professor and Head of the Department of Political Science at the University of Cincinnati (UC) and co-director of the Ohio Cyber Range Institute and center for Cyber Strategy and Policy. In 2017, he served as the inaugural US-UK Fulbright Scholar in Cybersecurity, University of Oxford, United Kingdom and in 2016 as the first scholar-in-residence at US Cyber Command and National Security Agency. He provides analysis to government agencies, including the US Defense and State Departments, US Senate testimony, and to US Congressional members and staffs as well as to US allies and served as red team member to the Cyberspace Solarium Commission.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any agency of the US government or other organization.

No comments:

Post a Comment