By George Friedman

Belarus, whose recent elections are making waves throughout the media, has been a pending flashpoint in Europe for some time. The reasons for this are history and geography.

Since the 18th century, Russia’s national security has depended on buffer zones to the west and south. During that time, it has faced four major invasions: by Sweden, allied with Poland and Turkey, to the south; by France, through the North European Plain; and by Germany, twice, through Poland and Ukraine.

Three things saved Russia in all four invasions. One was the distance that each invader had to pass to reach the Russian heartland, a distance created by Russia’s vital buffer zone. The second was the long, hard winters, which made supply, movement and survival difficult. The third was the massive if poorly trained forces Russia could mount as it retreated eastward.

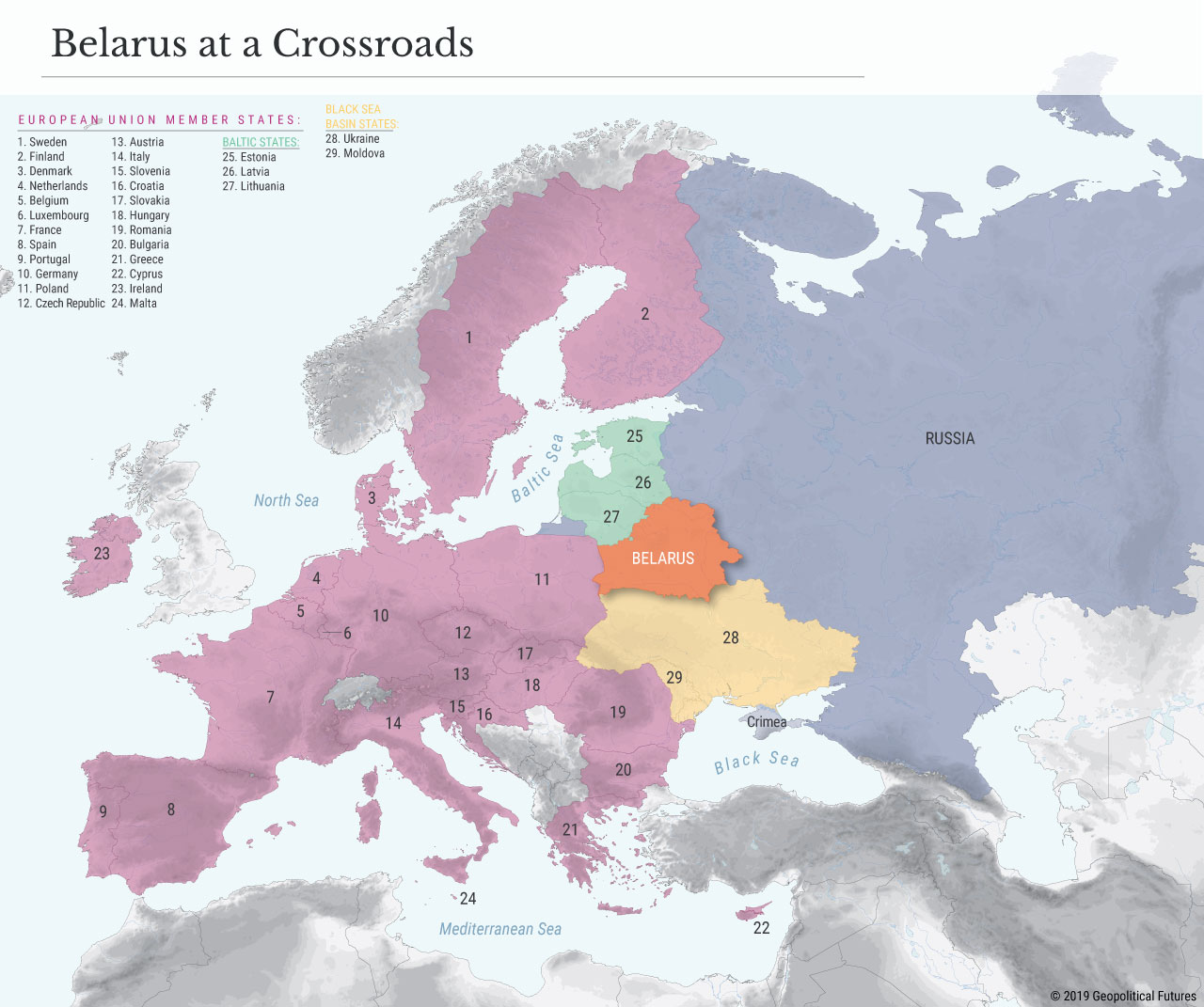

Russian President Vladimir Putin has called the fall of the Soviet Union the greatest geopolitical disaster in history. It is certainly true of Russian history, for it deprived the Russian Federation of its buffers. The Baltics were integrated into NATO, and in Ukraine, a political rising Moscow said was organized by the United States established a pro-Western government. To give these changes a sense of measurability, during the Cold War, the closest NATO member was nearly 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) from Leningrad (now St. Petersburg). Now, the closest is just 100 miles from the city.

The issue is not whether NATO or the U.S. intends to attack. It’s that over time intentions change. Russia, like any country, does not condone courses of action that could eventually be used against it. Indeed, the eastward movement of NATO, and particularly the Americans, created threats to Russia from the Baltics and Ukraine. If Ukraine were integrated into a U.S.-led coalition and fully armed, hostile forces would be less than 700 miles from Moscow. Russia could not tolerate this, so it seized Crimea, putting itself in a position to threaten the Ukrainian mainland and block Ukrainian ports, and dispatched special operations forces into eastern Ukraine to trigger a pro-Russian uprising. The uprising failed, but it has nonetheless effectively partitioned Ukraine enough to force the central government in Kyiv to back away from its border with Russia.

Moscow knew that losing Ukraine would leave it vulnerable to future attacks, but it also knew that the U.S. had no desire for all-out conflict. So they came to an unwritten understanding whereby the Russians would contain the rising in eastern Ukraine, and the United States would not give Ukraine offensive weapons. Essentially, the buffer zone was no longer under Russian control but still gave Russia the strategic depth it would need to respond if the agreement were breached.

And so we come to Belarus, around which all the Cold War drama unfolded but which remained relatively intact. Had U.S. forces ever occupied Belarus, they would have been able to threaten the Russian heartland directly. (Smolensk, a city that had been deep inside Soviet territory, would have become a border town.) On the other hand, had Russian forces taken control of Belarus and deployed on the western border, they would have been in a position to threaten Poland, and thus the rest of Europe, directly. After all, limited U.S. forces had already deployed in Poland, something that might deter Russia or lead to a major war.

The neutrality of Belarus has therefore always been extremely important to NATO. But it’s more complicated for Russia. On the one hand, eliminating a potential threat in Belarus is an extremely high priority for Moscow. On the other hand, engaging the United States in direct combat, and occupying NATO territory, is not.

Russia has resisted the temptation to undermine Belarusian neutrality, even as it has used Minsk’s economic needs to serve its own interests. Wanting neither to be subsumed by Russia or the West, President Alexander Lukashenko has carefully balanced between the two, which he has done by tightly controlling internal politics and intimidating his political enemies. Hence why he has been in power since 1994. The idea that Belarusians are upset at his continuous electoral success is unclear. Many are, others are not, and others still likely felt no urgent need to speak out on the issues. For the most part, Lukashenko has been accepted, and life has moved on.

This weekend’s elections are different. There is substantial opposition to the incumbent, so much so in fact that he had a rival candidate arrested. It was clear that Lukashenko was nervous about the election. He was particularly angry toward the Russians, saying that they had sent paramilitaries into the country, and implying that the Russians were trying their own Maidan Square rising.

It’s interesting that he is pinning the blame on Russia. Maybe that’s because he assumed the opposition was liberal and would balk at the idea of Russian assistance. Maybe Russia is trying to warn Belarus that the West is not a balance to Russia. Or maybe he’s right, and Russia is trying to reclaim an otherwise neutral buffer zone.

In any case, Lukashenko won an overwhelming victory, to no surprise. The issue now is not whether this will trigger an uprising, but whether outside powers, particularly Russia, might be working to redefine regional politics. From Russia’s perspective, this is rational, and now is a good opportunity. U.S. elections always distract Americans, and the EU is battling itself over coronavirus economics. Poland would be appalled, but Poland lacks the ability to act.

Leaders change, but geography doesn’t. Elections are frequently less interesting than the aftermath.

No comments:

Post a Comment