By Antonia Colibasanu

After 10 years of negotiation, the European Council earlier this week authorized the EU to sign a trade agreement with China. The deal will protect geographical indications, a type of intellectual property for products like Camembert cheese from Lower Normandy and Prosecco from Veneto that possess certain qualities unique to their place of origin. The agreement will prevent these kinds of products from being produced elsewhere and sold using expressions such as “kind,” “type,” “style” and “imitation.” The deal may not sound like much; it covers just 100 products from each side, and some EU members are more represented than others on the list of products. (French goods, for example, represent a quarter of the protected products.) But it is notable that the EU, at this critical time, is laying the groundwork for a broader trade agreement with China.

Indeed, the timing of the deal is interesting. It had been under negotiation for a decade, a long time even by EU standards, and it still needs approval from the European Parliament (which is mostly a formality at this point) before it can take effect. Moreover, the European Commission called China a “strategic competitor” as recently as 2019, and opinion polls indicate an increase in unfavorable views of the country among the European public.

The COVID-19 pandemic only added to these negative perceptions. Beijing made several efforts to control the narrative about the pandemic in the early days of the European outbreak, including by offering medical assistance to Italy, one of the countries most affected. But it seems these efforts didn’t help. According to the European Council on Foreign Relations, perceptions of China have worsened since the beginning of the outbreak. So, why did EU member states decide that now – during a European Council meeting in which the long-awaited coronavirus recovery plan was also being negotiated – was the right time to reach consensus on an agreement with China considering the economic challenges ahead?

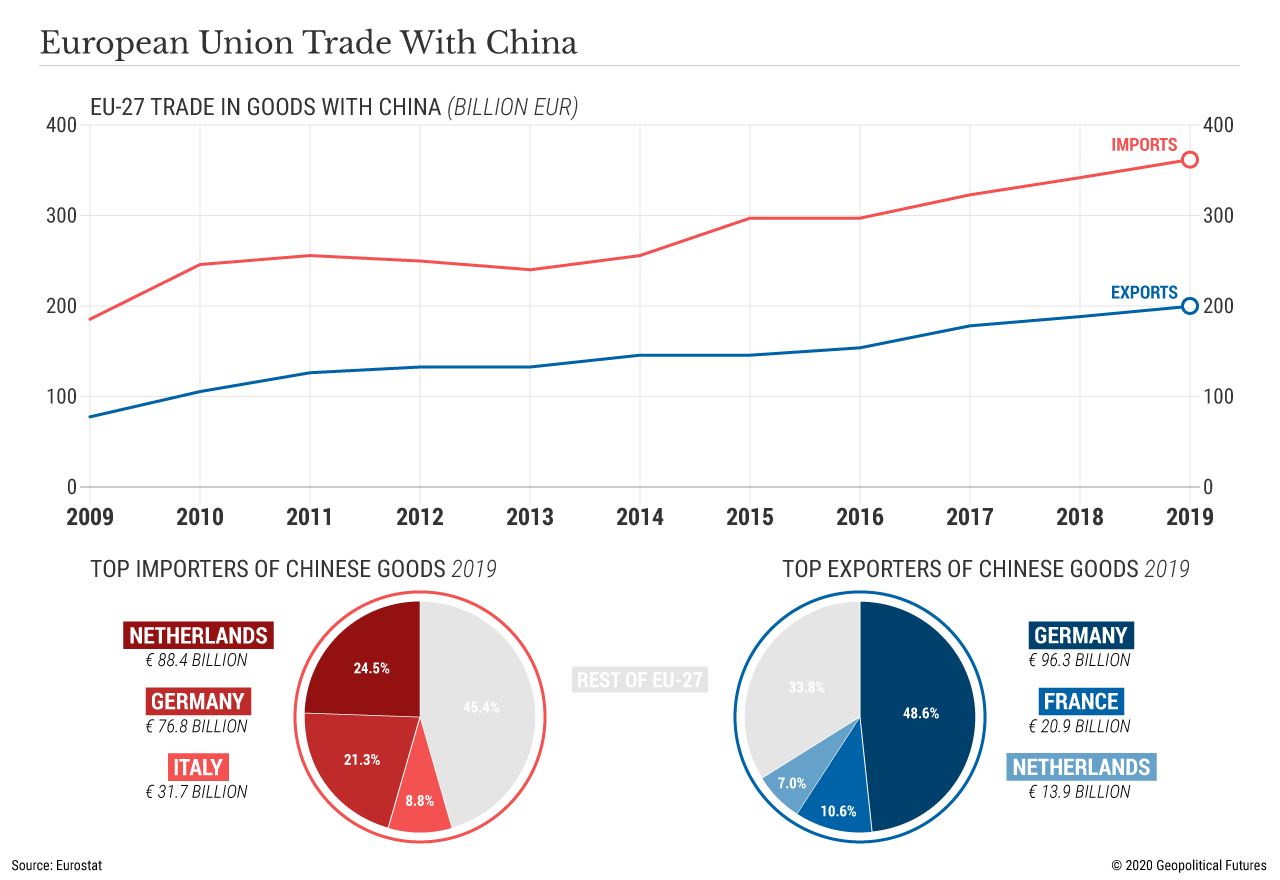

The answer lies in what China has to offer the EU, economically but also strategically, during a critical moment for the bloc. In 2019, China was among the EU’s largest export destinations, second only to the U.S., and top source of imports. In the past decade, European exports to China have more than doubled – from 77 billion euros ($88 billion) in 2009 to 198 billion euros in 2019 – and imports from China have also increased. China’s top trade partner in the EU is Germany, followed by the Netherlands and France. These three countries’ trade with China accounted for more than half (58 percent) of the EU’s total.

Germany alone accounts for a third of EU-China trade and is the only country out of the top three that has a positive trade balance in goods with China. This is not by chance; it’s part of Germany’s long-standing strategy toward China. After the Cold War ended, and especially after the 1997 Asian crisis, Germany realized the value not just of the Chinese market but also of low-cost Chinese manufacturing products that would make the German supply chain more efficient. Although France too saw Beijing as a potential strategic partner at the time, it was Germany that managed to establish itself as China’s top European ally, holding the spot as its largest trade partner since 1998. The two countries also shared common views on certain global affairs, notably both opposing the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 and NATO’s military intervention in the Libyan civil war.

As Germany grew into an export powerhouse, finding and growing new markets for trade was key. Between 1998 and 2005, the volume of trade between Germany and China tripled, and since 2005, German exports to China have increased fivefold to just under 100 billion euros last year. The benefits of this relationship were most apparent following the 2008 financial crisis, when U.S. demand for German goods collapsed. To offset the losses, Germany relied on China, which was largely unharmed by the economic turmoil at the time. While most of its exports still went to the rest of the EU, Germany increased its trade share with China, while also continuing to export to the United States. In 2019, exports to the U.S. accounted for 18.9 percent of total German exports, while exports to China accounted for 15.3 percent.

Over time, there has also been increasing convergence between the two countries’ economies. In the early 2000s, most of the manufactured goods that China exported to Europe were information and communication technology products, which include anything from personal computers to audio-video equipment, and industrial components. As China grew, it needed expertise in producing industrial technology, and Germany seemed to fit the bill. Now, China also exports machinery, in addition to ICT products, to the EU, and Germany in particular. As for German exports to China, they are similar in both quantity and quality to those destined for the U.S. and include automobiles, industrial equipment and machinery, as well as pharmaceuticals.

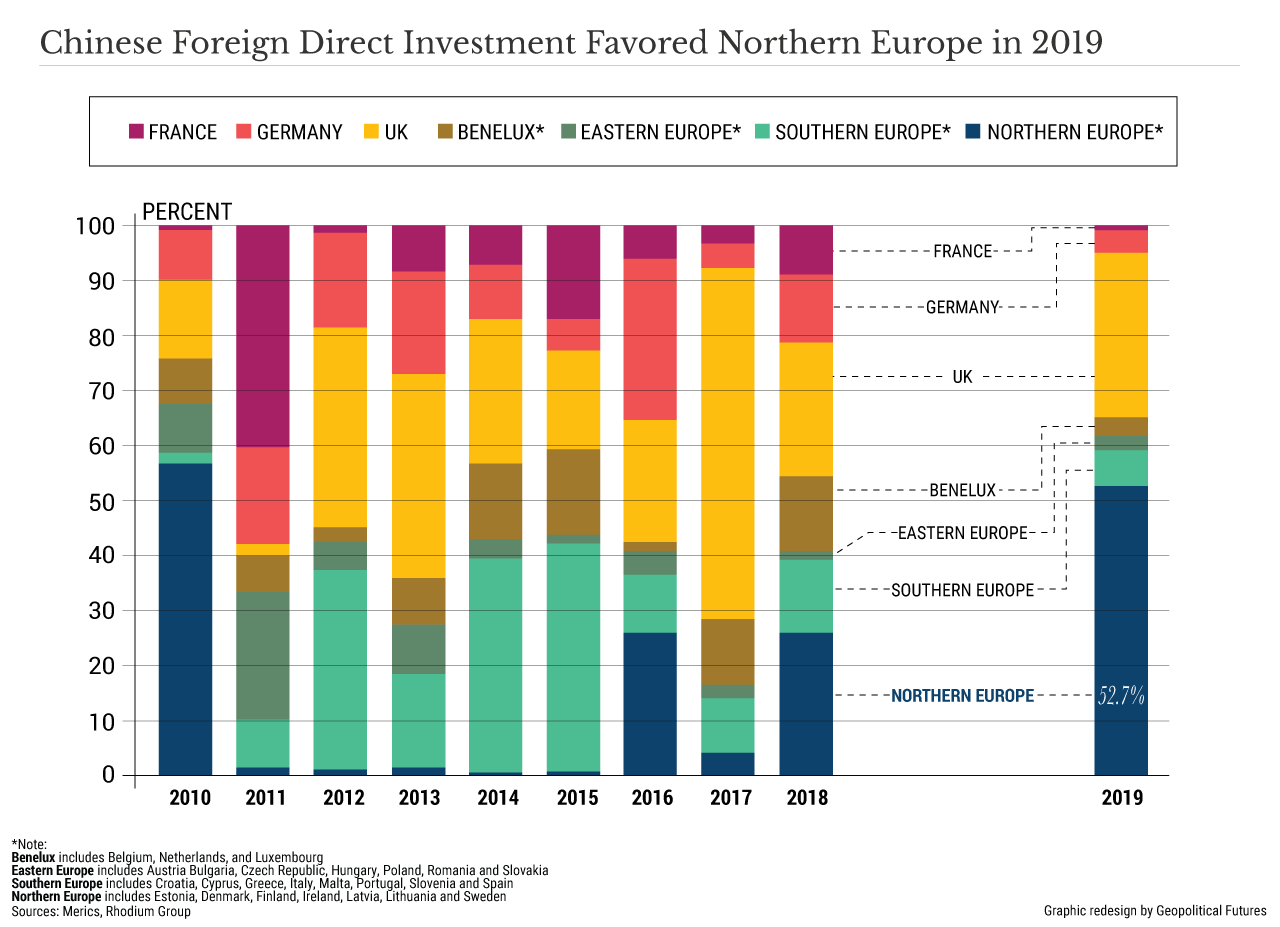

In 2009, China overtook the U.S. to become the largest buyer of new cars in the world, making it a critical market for the all-important German auto industry. Between 2005 and 2011, the Chinese auto sector grew by 24 percent annually. And since 2010, economic ties between Germany and China have strengthened. In fact, while Chinese spending in Central and Eastern Europe has grabbed the most headlines, it is in Germany and France that Chinese investments have really grown over the past decade. And Germany has, in turn, invested in China, with more than 500 German firms taking advantage of China’s low-cost production over the past five years.

This is why China plays such an important role in ensuring that the German economy doesn’t collapse during the current global downturn. While China is no replacement for the EU market, it can certainly mitigate the effects of shrinking U.S. demand. As the U.S. struggles to get the coronavirus outbreak under control, China seems to be gradually returning to business as usual. In June, for example, car sales grew by 11 percent, the third consecutive monthly increase, after months of decline. And unlike the U.S., which is becoming increasingly protectionist, China has actually been encouraging bilateral and multilateral partnerships.

In the long run, developing stronger ties with Beijing may get complicated, particularly because of human rights and security concerns, which are often high on the list of topics discussed during EU-China talks. In addition, while Germany and France, along with other Western countries, benefit from increasing economic links with China, Eastern European member states can’t say the same. Not only do they see limited economic advantages, but they also have an imperative to maintain a close strategic relationship with the U.S., on which they depend for their defense needs. And considering Beijing and Washington are currently embroiled in a trade war, it is unlikely that countries like Romania and Poland on Europe’s eastern frontier will accept a Brussels-backed shift to China that could put their relationship with the U.S. in danger.

But for the EU, reaching an agreement on geographical indications is a sign that it may be closer to signing a larger trade deal with China than with the United States. After all, Washington and Brussels failed to reach a similar agreement during talks on the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. Either way, the GI agreement seems relatively harmless. It secures the strategic German export relationship with China, promises more French sales in China and has gone virtually unnoticed by the Eastern Europeans. Along with hoping that the EU recovery plan works, it is the best Germany can do, for now.

No comments:

Post a Comment