In hopes of winning reelection, President Donald Trump is launching a new Cold War against the People’s Republic of China. Still focused on trade, however, his heart does not appear to be in his campaign—in contrast to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, who obviously enjoys launching rhetorical broadsides against Beijing. Pompeo also has been seeking allies willing to join a veritable economic war against China.

So far Pompeo has met with only indifferent success. The PRC’s economic reach makes countries reluctant to risk their relationship with China. Nations in East Asia, including allies such as Australia and South Korea, worry about security as well as economic ties. And no one has any confidence in a Washington administration that has leavened arbitrary incompetence with arrogant hypocrisy. If there is one U.S. president no one is inclined to follow, it is Donald Trump.

However, Washington has found an unexpected ally of extraordinary importance. This government could end up providing essential services in winning adherents to America’s cause. It is Beijing, which has been acting like, well, the Trump administration, maladroitly offending even those who should be China’s friends. The PRC seems to have decided to heed Machiavelli’s advice that it is better to be feared than loved. But China, also rather like the Trump administration, has pushed too hard, ending up loathed more than feared.

Although conspiratorial claims that COVID-19 was a nefarious Chinese plot to hobble America and defeat Trump rank alongside the fake moon landing and Bush administration responsibility for 9/11, the PRC disastrously mishandled the pandemic. Beijing’s increasingly brutal censorship which it insists is its “internal” concern had costly international consequences. Sending infected Wuhan residents overseas while controlling their movements at home was shockingly irresponsible.

Having done so much to turn a local infection into a global pandemic, China then compounded its offense by seeking to use its prodigious production of medical products to burnish its image. That set off an intense debate in the West about the downside of depending on a potential adversary for critical medical goods. Japan, long a target of Chinese nationalists, announced plans to spend $2.2 billion to help move industrial production out of the PRC.

Beijing compounded the damage to its reputation by sending defective medical materials, such as face masks, to countries desperately seeking assistance. After thereby hampering efforts to fight the disease, the Xi government derided other nations’ policies. For instance, China essentially accused the French government of killing nursing home patients, earning a swift rebuke from Paris. Chinese officials also pressed other nations to praise its performance.

When criticized, the PRC responded with vitriolic rhetoric and economic retaliation. “Wolf warrior diplomacy” became all the rage in China. But WWD, named after a favorite nationalist film hero, mimicked Trump administration behavior, which is not diplomacy at all. It is a fevered mix of insult, demand, threat, pressure, anger, and hostility. China’s ambassador to normally inoffensive Sweden, which had been angered by the kidnapping of a Chinese-born Swedish bookseller, announced that “We treat our friend with fine wine, but for our enemies we have shotguns.”

Another victim of Beijing’s rage was Australia, which proposed an international investigation of the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic. The PRC imposed tariffs on Australian goods and threatened to impose additional commercial penalties, causing Canberra to reiterate its demand and move closer to America. The Xi government warned the United Kingdom that the latter would “bear the consequences” of dropping Huawei from its 5G networks. PRC diplomats attacked Brazilian officials, including the president’s son, a congressman who referred to the “China virus.”

Beijing even targeted normally innocuous Canada, improbably warning against travel there because of “frequent violent actions” by the police. Bilateral relations deteriorated dramatically after Canada arrested a Huawei executive for whom the U.S. sought extradition. Days later China ostentatiously seized hostages, arresting two Canadians for allegedly stealing state secrets. They remain in custody.

The PRC’s iron-fisted behavior is not new. Although much fear has been expressed of late regarding the fabled Belt and Road initiative, poor nations long have found China’s embrace to be tight, even suffocating. Burma’s military junta began moving toward democracy in 2010 in part to bring back the West to balance Beijing. The readiness of Chinese mine supervisors to fire on striking workers made the PRC an issue in Zambia’s 2011 presidential campaign, in which the incumbent was defeated for reelection. Last year Malaysia’s new government suspended BRI projects, as the premier called China a “new colonizer” exhibiting “predatory” behavior. The two governments subsequently renegotiated the deal’s terms. Many countries have found the BRI to be a dubious benefit, unsurprisingly designed for Beijing’s rather than their benefit.

Worse, though, was China’s decision to repeatedly highlight brutal repression at home. The PRC has engaged in shocking misconduct: reeducation camps for Uighurs, closure of independent NGOs, intense persecution of all religious faiths, arrest of the human rights bar, tighter censorship, return to unlimited one-man rule. However, none of these had more impact than the decision to do a “Full Monty” with repression in Hong Kong, an international city whose autonomy had been guaranteed by Beijing through 2047. In full view of the world, China dumped its international commitments and brought the “one country, two systems” model to a dramatic end 27 years early.

Already countries are reacting against the PRC. Canada, Germany, Great Britain, Australia, and New Zealand all suspended their extradition treaties with Hong Kong. The territory argued that everyone was misinterpreting innocuous legislation of the sort used by all governments. It urged other states to wait to assess its implementation. Yet that process merely confirmed the fears of Hong Kong residents: last week a professor was fired and several students were arrested for past democracy activities. Legislative elections were delayed and democratic-minded activists were barred from running. A half dozen overseas residents, including an American citizen, were charged under the new law. The local authorities, who were not even shown the legislation before it was passed, have been reduced to puppets.

As if intent on tanking its reputation further, the PRC turned a border altercation with India into a bloody battle in which 20 Indian soldiers were killed. Although the details of the incident, along with the substance of the territorial dispute, remain complicated and obscure, Beijing is widely seen as the aggressor whose troops responded to initially peaceful contact with violence. Indians responded with a consumer boycott and the Modi government banned Chinese smartphone apps. New Delhi also is likely to move closer to America politically and militarily.

The incident offered a powerful reminder to China’s island neighbors of how the PRC could respond with its increasingly powerful navy in their many territorial disputes. Indeed, Japan reported that Chinese vessels regularly sail near the contested Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, which Tokyo administers. In May a Chinese ship sank a Vietnamese fishing boat near disputed islands; last year a Chinese vessel sank a Filipino fishing boat in contested waters.

Perhaps most dramatic has been the PRC’s loss of public and especially business favor in the U.S. Constant pounding from the administration, and the decision of presumptive Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden to match Trump in demonizing China, no doubt helped drive down the PRC’s ratings. However, Beijing has provided its critics with abundant fodder. A new Pew Research Center poll found that China’s unfavorable rating jumped from 47 percent to 73 percent over the last two years.

Even more significant has been the collapse in corporate backing for the U.S.-China relationship. Beijing long has been under fire from economic nationalists, national security hawks, and human rights activists. But over the last quarter century business stood behind expanded commercial ties. Some firms still do. And major exporters, such as the agriculture sector, continue to value the Chinese market. However, many exporters, and especially investors in the PRC, tired of regulatory discrimination, legal warfare, technology transfer, and IP theft, have backed the Trump administration’s trade war.

The loss of business backing undermined the foundation of the two nations’ bilateral relationship, especially since Trump was an economic nationalist open to protectionist arguments. Then came COVID-19 and attempts to blame the U.S. for creating and spreading the virus. The PRC helped create the fertile field for the president’s desperate reelection bid.

There is much speculation as to the cause of China’s compulsive PR self-immolation. Perhaps Beijing decided that the geopolitical environment, with the West on the defensive due to COVID-19, was an opportune moment to assert itself. Or the increased belligerency could reflect a more fundamental Chinese shift in policy to aggressive self-assertion. In either case, the PRC has helped stoke opposition.

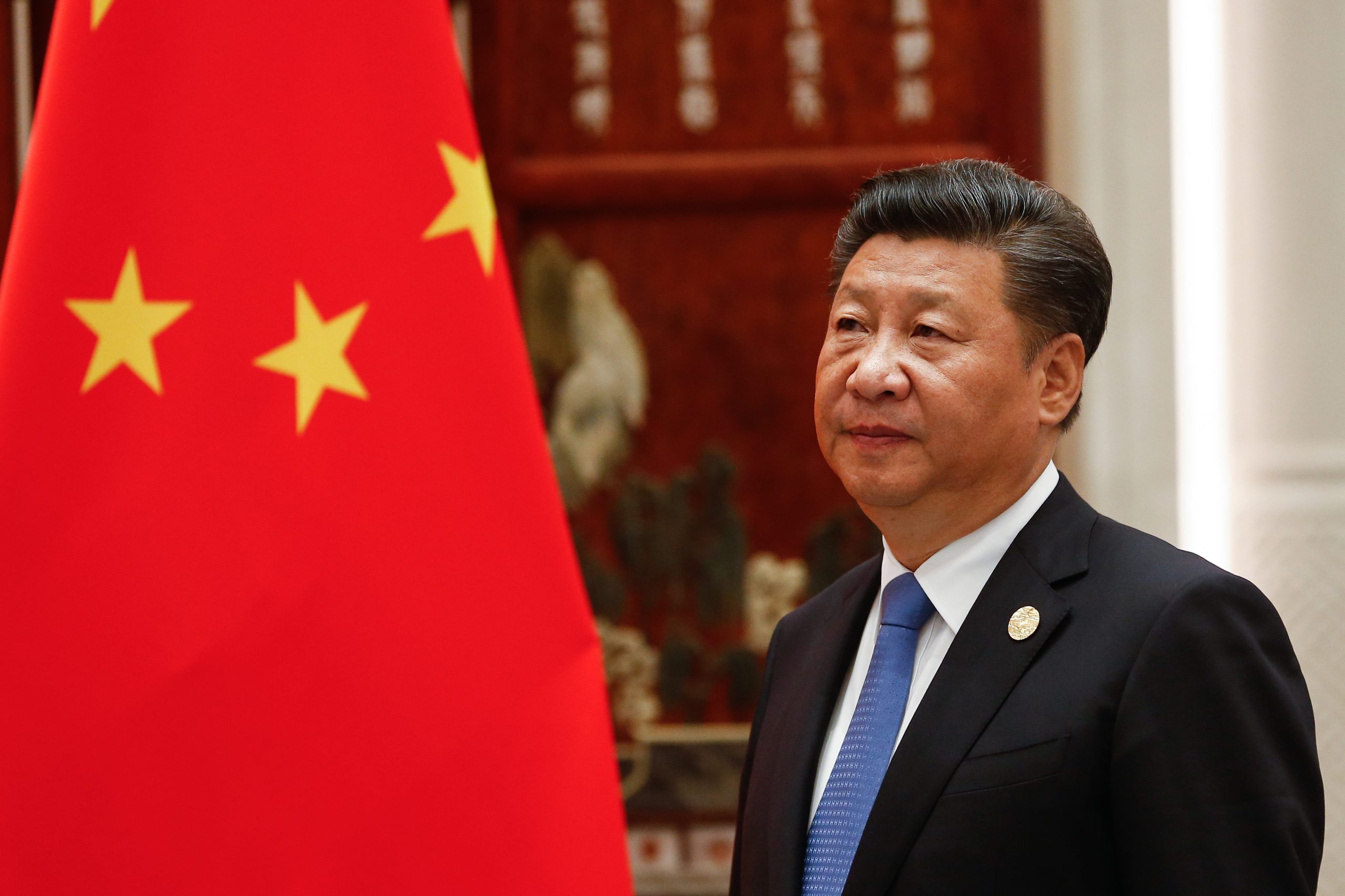

President Xi Jinping may stand upon the political summit at home. Abroad, however, he has degraded China’s reputation. The PRC has no close allies or friends. Instead, it has accumulated a gaggle of clients of dubious loyalty. North Korea has defended China’s behavior. Pakistan is uncomfortably dependent on Beijing’s largesse. Cambodia has routinely taken China’s position within ASEAN. Italy and Serbia profess gratitude for the PRC’s medical assistance. Russia continues an awkward, loveless embrace. A few developing states appear grateful for BRI projects, while remaining wary of debt dangers. This “coalition” will scatter in any serious showdown with America and the West.

None of this diminishes the serious challenge posed by Beijing to American values and interests. However, the U.S. should plan responsibly rather than react carelessly. If either country faces a crisis, it is China—bedeviled by economic weakness, catastrophic demography, geographic division, uncertain politics, and international blowback. So far the PRC has proved to be its own worst enemy.

Washington should rediscover the art of diplomacy, address its weaknesses, and enhance its attractiveness to others. If there is to be a contest, the way for America to win is to emphasize its strengths and rally its friends.

Doug Bandow is a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute. A former Special Assistant to President Ronald Reagan, he is author of Foreign Follies: America’s New Global Empire.

No comments:

Post a Comment