By Hilal Khashan

On Aug. 13, U.S. President Donald Trump announced a historic peace treaty between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, two countries that do not share borders and have never gone to war against each other. The agreement formalizes relations that have been improving since 2004, when Mohammed bin Zayed – the architect of the UAE’s interventionist foreign policy – became crown prince of Abu Dhabi, the deputy supreme commander of the Emirati armed forces, and, thanks to the poor health of his half-brother, the de facto leader of the country.

Under his rule, relations with Israel went from good to better. (Not even the assassination of a Hamas military commander by Mossad in Dubai in 2010 could shake them.) In 2018, the UAE invited Israeli athletes to participate in Abu Dhabi’s Judo Grand Slam and allowed them to display their flag and sing their national anthem. The Israeli minister of sports and culture accompanied the athletes and was invited by Emirati authorities to visit Abu Dhabi’s Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque. Last year, news emerged about a secret deal by which Israel would supply the Emirati air force with two sophisticated surveillance planes. The UAE allowed Israel to have its pavilion at the Expo 2020 Dubai (now postponed to 2021 because of COVID-19). MBZ persuaded Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, the chair of Sudan’s ruling Transitional Council, to meet with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in Uganda last February. The meeting allowed Israeli jetliners to fly over Sudanese airspace. As a gesture of goodwill, Abu Dhabi supplied Israel with 100,000 virus test kits last June.

Considering the excellent working relations between the two countries, did the UAE need to sign a controversial peace treaty with Israel? The answer to that question lies in the understanding that MBZ is a staunch anti-Islamist, a role that has made him a dedicated warrior against Islamists and a champion of the counterrevolutions of the Arab Spring. Put simply, his search for reliable allies is what prompted him to formalize his relations with Israel.

Selling the Deal

MBZ’s decision to officially recognize the state of Israel violates the conventional Arab wisdom that agreement to establish a Palestinian state must precede full normalization of relations. Emirati officials claim that they succeeded in averting West Bank annexation and put the Palestinians on the road to state formation. They add that normalizing ties was necessary to prevent Israel from annexing 30 percent of the West Bank and to revive peace talks for the two-state solution. Many Israelis do not see the UAE as changing the geopolitical reality of the Middle East since it does not obligate them to make concessions to the Palestinians. They approve of formalizing relations with the UAE because it costs Israel nothing and does not require them to change anything.

Netanyahu insists that the deal with the UAE postpones annexation and does not cancel it. Israel never unequivocally accepted the principle of statehood for the Palestinians, and its remarks on this matter have not exceeded vague lip service. The 1978 Camp David Accords mentioned Palestinian autonomy. Israeli perception of Palestinian self-determination is limited to self-rule in disjointed semi-autonomous enclaves. In 2019, Netanyahu spoke his mind about this issue: “A Palestinian state will not be created, not like the one people are talking about. It won’t happen.”

The best that Trump could say about suspending annexation was that “right now it is off the table.” The U.S. ambassador to Israel was more explicit: “It is not off the table permanently.” Emirati diplomat Omar Ghobash admitted that his country’s deal with Israel does not guarantee that it won’t annex parts of the West Bank. He said, “nothing is written in stone.” He seems to have accepted that the treaty does not give the Palestinians more than “breathing space” to resume the peace talks with Israel.

The Palestinian Authority reacted promptly by recalling its ambassador in Abu Dhabi. It characterized the agreement as treasonous to the Palestinian people. Hamas described it as a stab in the back. Palestinians of different affiliations now consider the UAE’s pretense of solidarity with them insincere and fraudulent. Arab skeptics took issue with the deal too. Western countries welcomed it despite outright Palestinian anger, sweeping condemnation among the Arab public and, except for support by the governments of Oman, Bahrain and Egypt, eerie Arab official silence.

The True Motives Behind the Deal

The fact is that the agreement is neither strategic nor historic. The UAE claims the deal comports with the 2002 Arab Peace Initiative that proposed full recognition of and normalization with Israel in exchange for establishing a Palestinian state with a capital in East Jerusalem. The initiative made normalization contingent on Palestinian statehood; the text of the recent deal blatantly neglected to address it.

The principals of the deal – the U.S., Israel, Saudi Arabia and the UAE – had plenty of reasons to move forward. All of them have problems at home, and all can use a political victory, however superficial: Trump is facing a tough reelection, Netanyahu is facing substantial financial corruption charges, Mohammed bin Salman worries that Joe Biden might question him on Jamal Khashoggi’s murder and other human rights violations, and MBZ’s staunch support for Trump could complicate relations with Biden if he wins the contest. (MBZ also has legal issues; a French court is deliberating whether the UAE should be charged with war crimes in Yemen.) Emirati officials believe that normalizing relations with Israel will give them a security blanket if Trump loses the election and Biden changes course on U.S. foreign policy. MBS and MBZ think the Jewish lobbies in the West are capable of shielding them from prosecution.

More strategically, the peace agreement is a response to the spread of Turkish influence in the region. Ankara’s ambitious regional policy and pan-Islamic disposition butts against MBZ’s interventionism – and his desire to turn his country into a leading power in the Middle East.

The timing is also notable. MBZ authorized the agreement one week after a rare virtual meeting between the foreign ministers of the UAE and Iran to exchange good wishes on one of Islam’s major festivals. It is unlikely that the Emiratis had not tipped the Iranians about their peace plans with Israel. Relations between the UAE and Iran have improved markedly in the past 18 months. Unlike many, the UAE did not accuse Iran of being behind the Fujairah oil tanker attacks in 2019. Abu Dhabi provided Iran with much needed COVID-19 testing kits and refrained from intervening in Yemen’s Houthi activities.

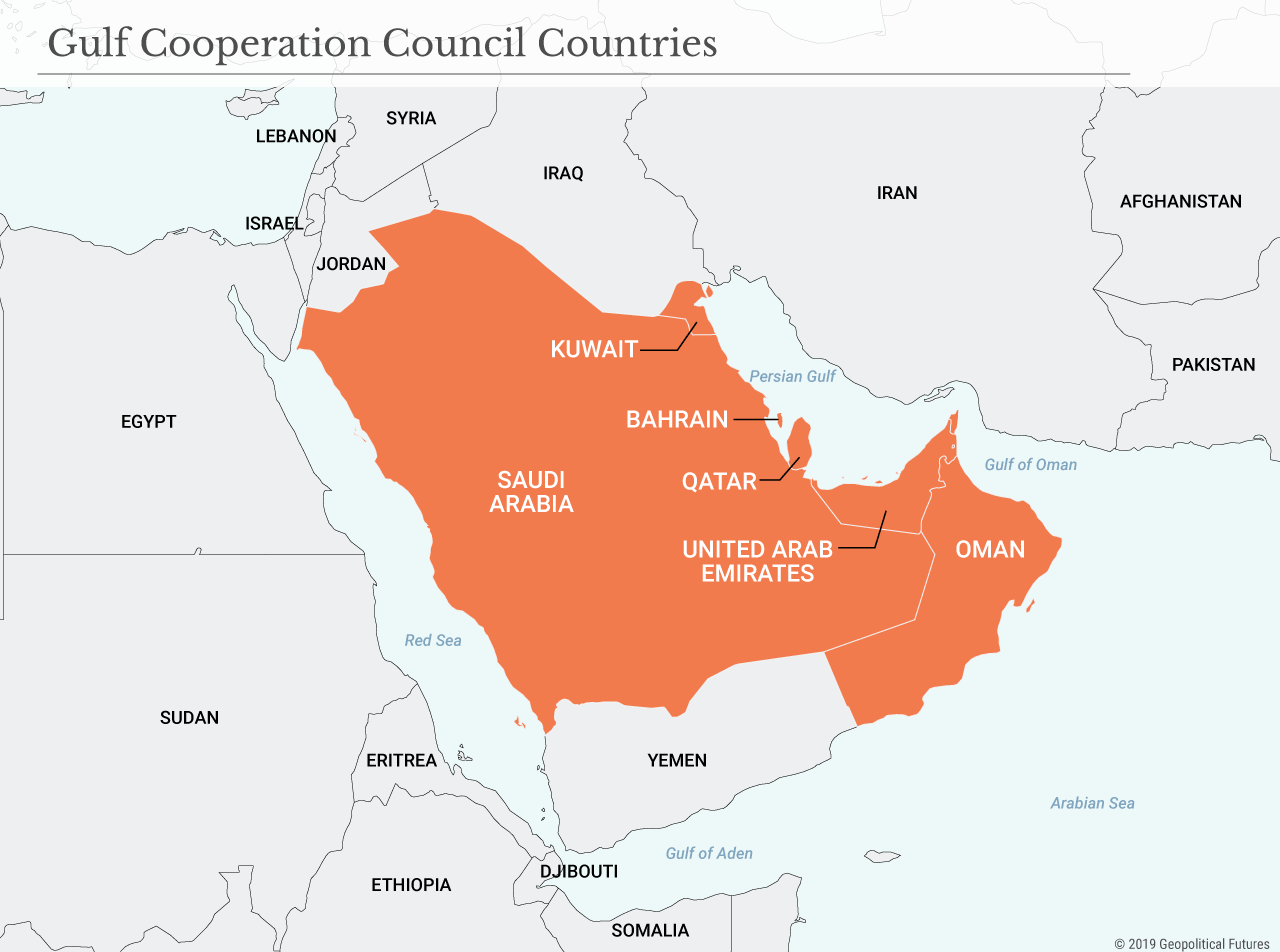

Ultimately, it’s all about the UAE protecting itself. Indeed, the search for security guarantors is a legacy for the Gulf Cooperation Council countries. The emirates that came together to form the UAE in 1971 all had protection agreements with Great Britain until 1971. Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait and Oman signed similar treaties with the British during the 19th century and early 20th century. In 1915, Ibn Saud signed the Treaty of Darin that effectively rendered his nascent state a British protectorate. The Quincy Pact in 1945 made Saudi Arabia a virtual U.S. protectorate. Yet they failed to create a unifying political vision and build a capable military force to protect their independence. They engage in centuries-old rivalries and feuds. It isn’t easy to imagine that the UAE, which cannot work transparently and constructively with fellow GCC member states, can work with Israel except as a junior partner. The UAE has succeeded in carving a niche in the international economic system as a dependent country with a flourishing services sector. One must not read into the Israel-UAE peace treaty outside this context.

No comments:

Post a Comment