By: Willy Wo-Lap Lam

Introduction

The central government of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has imposed sweeping new national security legislation on Hong Kong, which carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment for the crimes of secession, subversion of state power, terrorism, and “collusion” with foreign forces to jeopardize state security. The “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Safeguarding National Security in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region” (中华人民共和国香港特别行政区维护国家安全法, Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Xianggang Tebie Xingzhengqu Weihu Guojia Anquan Fa) was unanimously passed by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC), China’s parliament, on June 30 (NPC, June 30).

New PRC Institutions to Operate in Hong Kong

The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) legislature was not involved, and the bill was passed less than 30 days after it was first introduced at the full session of the NPC in late May (China Brief, May 26). There was no consultation by Beijing except with pro-establishment elements in the former British territory. While the majority of criminal cases under the new law will be handled by special courts set up by the HKSAR Government, a minority of particularly complex and sensitive ones will be dealt with by mainland judicial authorities. A new body to be set up in Hong Kong, called the Central People’s Government (CPG) Office for Safeguarding National Security in the HKSAR (中央人民政府駐香港特別行政區維護國家安全公署, Zhongyang Renmin Zhengfu Zhu Xianggang Tebie Xingzhengqu Weihu Guojia Anquan Gongshu) (henceforward “CPG Office”), will handle “complicated situations” of interference by foreign forces; cases that the HKSAR government could not handle effectively; and cases in which national security would be under “serious and realistic threats.” Such cases would be prosecuted by the PRC Supreme People’s Procuratorate and put on trial in mainland courts, where the full force of PRC law will apply (China.org.cn, July 1; Xinhua, June 30). The CPG Office will be in charge of investigations and intelligence gathering, and its activities will be beyond the control of the HKSAR city administration (China News Service, July 1; Southcn.com, July 1).

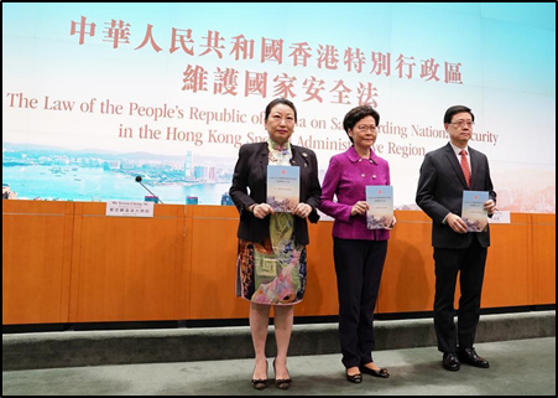

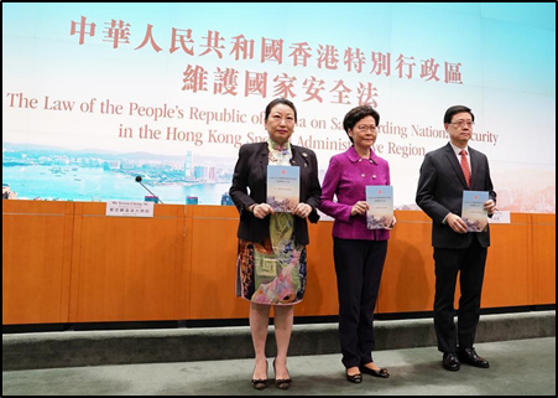

The majority of the national security-related cases will be handled by another newly established organ called the Committee for Safeguarding National Security in the HKSAR (香港特別行政區維護國家安全委員會, Xianggang Tebie Xingzhengqu Weihu Guojia Anquan Weiyuanhui) (henceforward “HKSAR Committee”). The Committee will be chaired by HKSAR Chief Executive (CE) Carrie Lam, and will put into place national security-related units in the Hong Kong police, the Department of Justice, and the judiciary. CE Lam will appoint a body of judges with specific responsibility for handling national security cases. Where “state secrets” or other matters of particular sensitivity are involved, there will be no trial by jury. Mainland authorities will appoint an advisor from Beijing to sit on the commission. Further, citizens cannot challenge the decisions of the commission by launching a judicial review. The CE can authorize phone tapping and other types of surveillance of suspects. Another disturbing thing about the new statute is that Beijing is empowered to station police and state security agents in Hong Kong, who will report to the CPG Office—and who will not be subject to most restrictions of Hong Kong laws. Image: HKSAR Chief Executive Carrie Lam (center), flanked by HKSAR Secretary for Justice Teresa Cheng (left) and HKSAR Secretary for Security John Lee Ka-chiu (right), attends a July 1 press conference to promote the new Hong Kong National Security Law. (Image source: Xinhua, July 1)

Image: HKSAR Chief Executive Carrie Lam (center), flanked by HKSAR Secretary for Justice Teresa Cheng (left) and HKSAR Secretary for Security John Lee Ka-chiu (right), attends a July 1 press conference to promote the new Hong Kong National Security Law. (Image source: Xinhua, July 1)

Image: HKSAR Chief Executive Carrie Lam (center), flanked by HKSAR Secretary for Justice Teresa Cheng (left) and HKSAR Secretary for Security John Lee Ka-chiu (right), attends a July 1 press conference to promote the new Hong Kong National Security Law. (Image source: Xinhua, July 1)

Image: HKSAR Chief Executive Carrie Lam (center), flanked by HKSAR Secretary for Justice Teresa Cheng (left) and HKSAR Secretary for Security John Lee Ka-chiu (right), attends a July 1 press conference to promote the new Hong Kong National Security Law. (Image source: Xinhua, July 1)

The most eye-catching appointment to the HKSAR Committee is its advisor Luo Huining (骆惠宁), who is sometimes deemed even more powerful than CE Lam. Luo, a Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Central Committee member and former party secretary of Qinghai and Shanxi Provinces, was earlier this year appointed as Director of the Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in the HKSAR (henceforward Central Liaison Office), as well as a Deputy Director of the State Council’s ministerial-level Hong Kong Macau Affairs Office (HKMAO). (Xinhua, July 3; HK01.com, July 3; BBC Chinese Edition, July 3). Given that Luo is in charge of the underground CCP in Hong Kong, he is also the de facto Party Secretary of Hong Kong.

Also in early July, Beijing authorities appointed the senior officials of the CPG Office, who will be stationed in Hong Kong. The office head is Zheng Yanxiong (郑雁雄), a former secretary-general of the CCP Committee running Guangdong Province. Zheng, who speaks Cantonese (the main dialect used in Hong Kong) is noted as a tough enforcer—particularly in suppressing riots and demonstrations in Guangdong. Although Zheng is only vice-ministerial in rank, he will be instrumental in promoting synergy between the police and state-security personnel in Guangdong and those in the SAR. Zheng’s first deputy, Li Jiangzhou (李江舟), earned his spurs in the Ministry of State Security, China’s spy agency. Since 2016, he has been based in the Central Liaison Office in Hong Kong; his role is to promote liaison between mainland security and police forces and their counterparts in the SAR. Little is known about Sun Qingye (孙青野), the second deputy head of the PRC Office, except that he, too, built his career in the Ministry of State Security (Apple Daily [Hong Kong], July 3; Radio France International, July 3).

Overriding the Hong Kong Legal System

The NPC Standing Committee has ultimate powers over the interpretation of the new law, which will override all existing legislation in the HKSAR. Article 62 of the National Security Law says: “This Law shall prevail where provisions of the local laws of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region are inconsistent with this Law.” Questions of interpretation are important because the mainland does not follow Hong Kong’s British common law system. Take the issue of “collusion,” for which there is no definition in the existing Hong Kong legal system. Under Article 29 of the National Security Law, “a person who steals, spies, obtains with payment, or unlawfully provides State secrets or intelligence concerning national security for a foreign country or an institution, organization or individual outside the mainland, Hong Kong and Macao of the People’s Republic of China shall be guilty of an offence [under collusion]” (Xinhua, June 30).

Similarly, a Hong Kong resident will be found guilty of collusion if he or she conspires with a foreign entity for the purpose of “provoking by unlawful means hatred among Hong Kong residents towards the Central People’s Government or the Government of the Region, which is likely to cause serious consequences.” Such concepts not only are alien to the Hong Kong tradition, but effectively set severe limits on interactions between Hong Kong residents and foreign organizations and NGOs. Article 54 also states that the CPG Office, alongside the Office of the Commissioner of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Hong Kong and the HKSAR government, must adopt measures to “strengthen the management” of Hong Kong-based foreign NGOs and media agencies. In a striking assertion of the law’s international reach, the NSL goes so far as to say that foreigners living outside Hong Kong might be implicated: Article 38 states that “this law shall apply to offences… committed against the HKSAR from outside the Region by a person who is not a permanent resident of the Region” (Xinhua, June 30).

Changes to the Way That Hong Kong Is Ruled

Apart from legal issues, the passage of the legislation reflects subtle changes in the way that Beijing will be running Hong Kong. Members of the Hong Kong elite—business tycoons and senior civil servants, who were highly respected by Deng Xiaoping—have been kept out of the loop. The drafting of, and deliberations over, the law have been tightly controlled by the newly-established Central Leading Group on Hong Kong and Macau Affairs (中央港澳工作领导小组, Zhongyang Gang-Ao Gongzuo Lingdao Xiaozu) (hereafter, “Leading Group”) (Ta Kung Pao, June 4; Caixin, June 4). The Leading Group is headed by Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Politburo Standing Committee member Han Zheng (韩正)—and ultimately responsible to the supreme leader, CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping. The two sub-heads are Xia Baolong (夏宝龙)—the recently appointed Director of the Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office (HKMAO), and a Xi protégé—and Minister of Public Security Zhao Kezhi (赵克志) (China Brief, February 21). In an internal speech in late May, Zhao caused a stir when he called on the mainland police to give “support and guidance” to their counterparts in the HKSAR (Radio French International, May 29; rthk.hk, May 29).

In post-National Security Law Hong Kong, HKSAR-based mainland cadres could be calling the shots above the heads of CE Lam and her ministers. Of particular importance is the Director of the CPG Office, Zheng Yanxiong (郑雁雄). Even more pivotal will be the role of Luo Huining, the mainland advisor sitting on the HKSAR Commission. “Since the National Security Legislation overrides all other laws in Hong Kong, the office overseeing its implementation will naturally assume a lot of authority,” said veteran Sinologist and author Ching Cheong. “As for Carrie Lam’s advisor on the HKSAR Commission, he will function as political commissar to ensure that everything is being done to the CCP’s satisfaction” (HKC News, June 20). Image: Demonstrators arrested by police at the Times Square Mall in Hong Kong, July 1. Hong Kong police moved immediately following the announcement of the National Security Law to crack down on protests in the territory. (Image source: SCMP, July 1)

Image: Demonstrators arrested by police at the Times Square Mall in Hong Kong, July 1. Hong Kong police moved immediately following the announcement of the National Security Law to crack down on protests in the territory. (Image source: SCMP, July 1)

Image: Demonstrators arrested by police at the Times Square Mall in Hong Kong, July 1. Hong Kong police moved immediately following the announcement of the National Security Law to crack down on protests in the territory. (Image source: SCMP, July 1)

Image: Demonstrators arrested by police at the Times Square Mall in Hong Kong, July 1. Hong Kong police moved immediately following the announcement of the National Security Law to crack down on protests in the territory. (Image source: SCMP, July 1)

Reactions in Beijing, Hong Kong, and Abroad

Mainland offices and cadres have praised the National Security Law for setting “one country, two systems” on the right path: “This law will be a sharp sword hanging over a minority of people who endanger national security,” said the ministerial-level Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office. For most HKSAR residents, it said, the law will be a “guardian angel that safeguards their rights, freedom and peaceful way of living” (South China Morning Post, June 30). Serious misgivings, however, have been expressed by Hong Kong’s pro-democracy politicians, and members of the legal community. “The National Security Legislation has signed the death certificate for ‘one country two systems’,” said Civic Party legislator Tanya Chan. “It’s now one country, one system.” Eric Cheung Tat-ming, principal lecturer at the Hong Kong University Law School, spoke for many when he said that the legislation reflected the spirit and practice of the mainland legal system. “The role of Hong Kong courts in interpreting the law may be severely limited,” he said (Ming Pao [Hong Kong], June 30; rthk.hk, June 30). The Hong Kong Bar Association has pointed out the conflict of interest involved in Chief Executive Lam appointing judges in her capacity as Chairman of the HKSAR Commission, and further lamented the lack of trial by jury in specific cases (BBC Chinese Service, July 1; Hong Kong Bar Association, June 23).

Internationally, the passage of the controversial legislation has had the effect of exacerbating China’s differences with Western countries, particularly the United States. The reaction from the United States has been predictably strong. Both the House of Representatives and the Senate unanimously passed the Hong Kong Autonomy Act, which President Trump signed into law on July 14. The Act, together with an executive order issued by the U.S. president on the same day, essentially removed all the trade and other privileges accorded to Hong Kong as a special customs zone distinct from mainland China (White House, July 14).

Furthermore, unnamed PRC officials responsible for the NSL may be subject to sanctions: for example, multinational banks and other companies that do business with these mainland officials may be penalized. President Trump went so far as to assert that “actions taken by the PRC to fundamentally undermine Hong Kong’s autonomy…. constitute an unusual and extraordinary threat” to American national security (Hong Kong Free Press, July 15; U.S. Consulate in Hong Kong, July 14). At this stage, however, it is unlikely that Washington would do anything to the Hong Kong dollar-U.S. dollar peg. However, a certain number of Chinese enterprises may be barred from the U.S. stock exchange, as well as the U.S. banking system.

In fact, what the CCP fears most—a united front among Western countries against China—seems to have formed due to the Hong Kong issue. The United States, United Kingdom, and Canada have suspended extradition treaties with Hong Kong. The British, Australian, and Canadian authorities have indicated they might consider accepting more immigrants from the HKSAR. The United Kingdom, Germany and France have decided to stop selling police equipment to the SAR Government. The German Federal President Frank-Walter Steinmeier has further stated that the NSL would cause a “lasting, negative” change to Western perceptions of China. (Taiwan News, July 13; Ming Pao [Hong Kong], July 9; Radio France International, July 2).

Earlier, both the leaders of the Group of Seven (G7) countries and the European Union issued statements condemning the diminution of the HKSAR’s high degree of autonomy. The European Parliament has requested that EU authorities take the Hong Kong case to the International Court of Justice in the Hague (Channel News Asia, June 20; Deutche Welle Chinese, June 20). In Japan, Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga said on June 30 that the NSL was “regrettable;” and Foreign Minister Toshimitsu Motegi indicated he shared the “deep concern” of the international community and the Hong Kong people over the legislation (News Now [Hong Kong], June 30).

Conclusion

For the moment, PRC authorities seem satisfied with the intimidating effects of the draconian new law. Several radical groups advocating Hong Kong self-determination—including Demosisto, which is led by famous democracy advocate Joshua Wong—disbanded on June 30. While thousands of Hong Kong residents staged protests on July 1 (a HKSAR holiday marking the reversion of Hong Kong’s sovereignty to China), the numbers were lower than expected. Three hundred seventy demonstrators were arrested, including 10 on charges relating to the National Security Law (Ming Pao, July 2; Hong Kong Free Press, June 30). Although HKSAR residents might be forced into acquiescence in the near term, a new and potentially deadly front of confrontation has been opened between Beijing and the 7 million HKSAR residents. Twenty-three years after Hong Kong became Chinese territory, the vaunted “Chinese model” has turned away more residents—even as the hardline authoritarian regime of Xi Jinping resorts to brute force to cow Hongkongers into subservience.

Dr. Willy Wo-Lap Lam is a Senior Fellow at The Jamestown Foundation and a regular contributor to China Brief. He is an Adjunct Professor at the Center for China Studies, the History Department, and the Master’s Program in Global Political Economy at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He is the author of five books on China, including Chinese Politics in the Era of Xi Jinping (2015). His latest book, The Fight for China’s Future, was released by Routledge Publishing in July 2019.

No comments:

Post a Comment