Rameez Raja and Zahoor Ahmad Dar

The tilt in the geography of power from a “unipolar moment”, characterised by American dominance in the global distribution of power, to the waning of American supremacy is not a unipolar illusion, but rather a reality. The United States (US) as a dominant actor has shaped and mapped global politics without being balanced by other great powers since the collapse of the erstwhile Soviet Union. Kenneth Waltz, the neo-realist thinker, argued that the balance of power will recur. However, this factor concerning the non-cognizance of temporality in relation to balancing strategies has been discounted by realist scholarship. The hegemonic positionality of the US, by virtue of its superiority in Command of Commons as well as its offshore balancing strategies, has been quite successful in deterring rising powers. While contextualising this in China’s case, Washington’s policies seem to be less effective.

The tilt in the geography of power from a “unipolar moment”, characterised by American dominance in the global distribution of power, to the waning of American supremacy is not a unipolar illusion, but rather a reality. The United States (US) as a dominant actor has shaped and mapped global politics without being balanced by other great powers since the collapse of the erstwhile Soviet Union. Kenneth Waltz, the neo-realist thinker, argued that the balance of power will recur. However, this factor concerning the non-cognizance of temporality in relation to balancing strategies has been discounted by realist scholarship. The hegemonic positionality of the US, by virtue of its superiority in Command of Commons as well as its offshore balancing strategies, has been quite successful in deterring rising powers. While contextualising this in China’s case, Washington’s policies seem to be less effective.

Why and how is the American position of pre-eminence challenged and extended deterrence restrained by growing Chinese assertions? Equally, how is the American agenda of taming and containing China in the Asian Hemisphere through the use of India as a buck-passer falling short of India’s own burgeoning challenges? Why is India not an effective balancer vis-a-vis China is also a critical question to pose. This discussion will seek to address these questions in light of the changing geography of global power that we are bearing witness to today.

Theorising China within Power Transition Theory

With the rise of ‘the rest’, the West is losing its dominance, argues Charles A. Kupchan (2012). Kupchan (2002) postulates the waning of US primacy and the onset of a multipolar world. However, the question arises: will the multipolar world ensure durable peace and security? Offensive Realists, such as John Mearsheimer (2014), argues that an unbalanced and multipolar world is dangerous for global peace and security. An unbalanced multipolar world order without a strong dominant power intensifies vulnerability. During the Second World War, revisionist powers like Japan and Germany attacked other strong powers like the US to regain status and power, but were defeated. During the 1930s and 40s, the world was unbalanced and its structure of power one of multipolarity, increasing the bandwidth of antagonism between competing states. The ensuing security dilemma made every region increasingly dangerous and vulnerable to the threat of war. However, we can apply the instances of the Second World War as a solution to the emergent crisis.

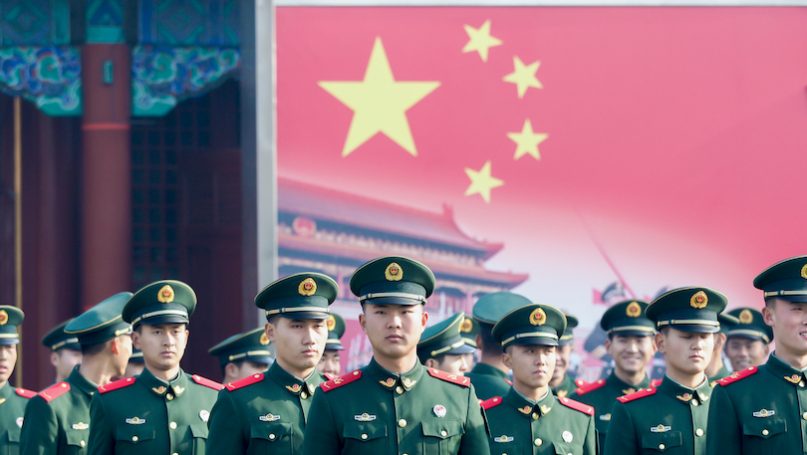

Defensive Realists such as Stephen Walt triangulates the genesis of a New Cold War between the US and China with the dispute over the South China Sea (The Economic Times, 2020). China has gained strong foothold within the international political structure as a result of its impeccable growth and development. The power projection by China with moral realism as its philosophical tenant has helped it to shape global narratives. Thus, China is rising but rising at the cost of American over-stretching and unilateral aggressiveness.

A question that has been much debated theoretically as well as politically in both academic and policy discourse is: can China rise peacefully? In this regard, A. F. K. Organski’s (1958) Power Transition Theory can unsettle the causation behind the issue of China as a rising power and US efforts to restrain it. Many significant voices in the US accused China of the Covid-19 pandemic and urged other states, especially the United Kingdom, to ban the Chinese private telecoms giant Huawei. What contributes to the exacerbation for Washington is the growth of China’s visibility and dominance in the Asian Hemisphere. These states, particularly Pakistan, Iran, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, collaborate with China out of a rationale based upon security and economic interest, reaping a number of benefits.

Power Transition Theory posits that an international arena has hierarchical power structure with a dominant power at the top and lesser powers following its lead, per the thought of Organski (1958). Contextualising this in China’s contemporary scenario, we can infer that China has massively extended its dominance in Asia, which puts it at the top in hierarchy. Thus, Pakistan, Iran, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh are informed of the pay-off structure that the dominant power forms under such conditions. India has been reluctant to accept China as the regional/dominant power, and it rather considers China as a potential peer competitor concerning security, especially since the 1962 Indo-China war. The economic prowess of China and India has also contributed to their advancing of military assets to establish their respective superiority in Asian Hemisphere.

Through complex interdependence, bilateral trade and commerce has prospered between China and India. However, intractable border issues have created an enduring thaw in their relations. Close geographical proximity escalates a dynamics of vulnerability. What complicates the problem further is the Indian bilateral and strategic closeness with the US. This can be seen as the extension of the US in India as an offshore balancer in the backyard of China in Asian Hemisphere. China’s intrusion in Ladakh is a strategic reaction to the growing closeness between India and the US regarding the South China sea. China’s rise is problematic for the US as this endangers its control and status as an effective Offshore Balancer in the Asian Hemisphere. Such a predicament becomes obvious in light of the argument made by Mearsheimer (2014), who argues that Asia will witness big troubles if China becomes increasingly more powerful. Logically, to tame China, the US has passed the buck to India.

China’s policies like the “Western Development Strategy” and “Look West” vision have increasingly penetrated South Asia (Palit, 2017) and are endorsed by weaker states. The promotion of its “Soft-Power” in non-military policies like public goods support, education and disaster management has attracted weaker states in Asia. However, India is yet to command a similar global pull, especially concerning the One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative where India has shown reluctance.

There is the possibility of an alliance building among China, Pakistan, Russia, Iran and Turkey. The US imposition of strict economic sanctions on Russia and Iran has forced them to knock at the door of Beijing. Also, Iran, Turkey and Pakistan as victims of the issues of Islamophobia have manoeuvred their options to bandwagon with China, in order to gain support. Pakistan is accused of harbouring UN-designated terrorists where China is seen as an option to mitigate the effects of this characterisation. In the case that the US, the United Kingdom, France and other US allies look for counter alliances, the world may indeed witness a deadly new cold-war with the potential for nuclear warfare. Currently, the world seems to be an unbalanced and multipolar, and as such the chance of war is more likely.

Provincializing India: Domestic Conditions Versus Foreign Imperatives

Elizabeth Hanson (2012) argues that the image of India as a poor country is sharp and clear, whereas its image as a democratic country is far more blurred. With the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) led government coming into power, institutional credibility reached its lowest ebb with excessive political intervention and politicisation. Mob-lynching’s, attacks on civil society activists and academic spaces, and the politicisation of the judiciary has led to greater systemic apathy towards the people. Criminalising minorities has become a new standard template.

Fiddling with the federal character, especially with regard to the sensitive region of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), is manifesting into the erosion of a democratic ecosystem through populist means. The state of J&K was unconstitutionally bifurcated into two new Union Territories and scrapping its status as an autonomous region dealt another blow to Indian democracy, which is purely exclusive in nature. The Indian Supreme Court is even silent on ensuring public goods such as the internet after New Delhi failed to restore 4G internet services in Kashmir. Also, the controversial Citizen Amendment Act (CAA) triggered widespread protests from Muslims across India and, consequently, in other parts of the world. However, the new government seems more concerned with its Hindutva project than with protecting minorities in India. This project requires some unpacking.

The Hindutva Project

The BJP led government has come to power with an absolute majority. Their politics is predicated on a Hindutva ideology, a cultural project. Their popularity was hinged on the dilution and abrogation of articles 370 and 35A. Sanjay Chaturvedi (2014) argues that Hindutva, as a security discourse, is underpinned by a distinction of ‘us against them’, dictated by a logic of threat. Similarly, the “Green Books” in Pakistan considered India as a Hindu nation, and thus a grave threat to Pakistan and Islam (Paul, 2014). Religion as an ideological tool is shaping the overarching political narrative in South Asia, especially where India and Pakistan are battling for superiority of their religions, adding certainly to the non-resolution of the Kashmir issue. The noted thinker on the topic Stephen P. Cohen (2013) grounds his argument on similar lines, claiming that religion is the primary cause for those prolonged and unsettled disputes between New Delhi and Islamabad.

The Historian Romila Thapar (2008) argues that the Hindu version of Muslim raids on Somanatha temple in India is a ‘memory’ that at the same time annuls the memory of Hindu Kings raiding Hindu temples. Currently, the BJP’s mission is to exclude the Muslims from Indian Territory, or rather, to declare them as second class citizens through the controversial CAA, simply because these are the progenies of Mahmud’s who raided India. What about the Hindus who equally raided Hindus temples? The human rights violations of Muslims in India (particularly in Kashmir) is a reflection of the hatred of hard-line Hindus against Muslims (othering) who are considered a threat to Hindutva.

The extremism of Hindutva forces is becoming discernible with the witch-hunting of minorities, criminalising the civil society activists, media censorship, institutional attacks and fake propaganda. Conceivably, India might follow Pakistan’s trajectory where theocracy is the dominant force in the public sphere. With Pakistani leaders lauding religion for their success, it invited extremism, militancy, terrorism, rampant corruption, ethnic violence and sectarianism. Pakistan is struggling to rescue itself form the tag of harbouring UN designated terrorists after Jihadi forces were praised for securing Islam and Pakistan. Similarly, the BJP’s communal agenda, based on exclusion and othering has unleashed a terror on the marginalised communities. The construction of Ram temple by demolishing a Babri mosque is tantamount to the murder of democracy. The Hindutva’s Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) is a militant organisation that promotes organised attacks on the minorities. The BJP led government, with its exclusivist agenda, is stifling democratic pluralism, consequently ostracising the survival of the “other”.

With this in mind, a state predicated on such majority tyranny may go on to fail if it continues to harbour and glamorise Hindutva projects. This has damaged the social cohesion that is pivotal for any diversity to flourish. Indeed, the external strength of any state is correlated and contingent upon its internal conditions.

Why do nations fail? Economists Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson (2013) have rejected the cultural hypothesis, the geography hypothesis, and the ignorance hypothesis for the economic prosperity of states. Here, they argued that extractive political and economic institutions are the primary factors that lead to the failure of states. Also, they argue that inclusive political and economic institutions are the chief qualities that help states to gain economic prosperity and political stability of the many states which are currently the developed states of the world. Growing economic and political instability in India indicates that the BJP led government is more concerned with turning the country into a Hindutva state, rather than assimilating the goodwill of the people. On the basis of this argument, the failure of institutions with excessive political intervention has led to both a credibility crisis as well as an acute lack of checks and balances, both resulting in further domestic instability. The space of the public sphere is diminishing in India, further marginalising the democratic space.

Bharat Karnad (2015) argued that despite India having achieved an emerging power status, due to soft power determinism, India’s weak hard power capability, including the absence of political vision, will have restricted India from achieving the global/great power status. Similarly, Karnad (2018) criticized the foreign and security policies of the Modi government. Here, Karnad argues that in the case that Modi will return to power with the next parliamentary elections, India’s capability to achieve the status of a global power would be setback as a result of Modi’s flawed foreign and security policies over the last four years. Additionally, the Indian economy has faced a chronic downturn since demonetisation. The economic indicators are quite dismal in fact. Indeed, an inept economy cannot become or support military power, since economic power is a great contributor to military might.

Externally, China’s offensive attitude towards India is the testimony of the Modi government’s flawed foreign and security policies. Engaging with Beijing is beneficial for New Delhi, as opposed to alternatively collaborating with the US to tame China. Beijing will not accept the US as an Offshore Balancer in Asia where China has grasped its power and position to dominate it. Therefore, with this in mind, US dominance is facing challenges with the growth of Chinese relative power positions.

China’s Strategic Behaviour

The US impression of China as an aggressor has helped the West to disengage with it. Strategically, the United States wants to tame China, however, Beijing is aware of its strategic interests too. Beijing’s rigid stance regarding Hong Kong in imposing the National Security Law (Carter and Wasserstrom, 2020) also reflects its strategic behaviour. Simply, it is the sign of a dominant power or the rising of a regional hegemon. Any state can behave aggressively if its strategic interests will be challenged by an Offshore Balancer. Despite this, China wants to rise peacefully, it is focusing on its military power by reinforcing both its nuclear and conventional forces to secure its strategic interests. Although China accepts its disparity with the US concerning the Command of Commons, Beijing is still powerful enough to protect itself from any mighty attack and simultaneously attack a strong state like the US. In comparison, although India is militarily strong, it would be naive to compare it with China.

India’s foreign and domestic policies are weak since the BJP came to power. China takes advantage of India’s flawed policies concerning the scrapping of the autonomy of J&K. An intrusion of Chinese troops in Ladakh has been linked with the unconstitutional bifurcation of J&K. China gave clear evidence that it is also a stakeholder in the unsettled Kashmir dispute. Though India claimed Kashmir as an internal matter, the international community is totally dissimilar in this regard. Pakistan, and now China, are part of the prolonged Kashmir dispute, but nowadays are unacceptable to India under the BJP led government.

Kashmir is at the centre of American policy too, that is why Donald Trump sought to meditate in order to resolve the core issue between India and Pakistan. Daniel Markey argues that many American Presidents thought that solving the Kashmir issue was a sure road to a Nobel Peace Prize (Cohen, 2013). Also, this change in US behaviour to resolving the Kashmir issue indicates that the US still designates itself as a dominant power in the Asian Hemisphere. This demonstrates how Washington wants to exclude Beijing as an arbitrating actor for resolving the core issues in South Asia. However, China’s fungibility of power with issues like Kashmir, Ladakh and the South China Sea depends entirely on its military and economic power, with its perceived strategic setting to dominate the Asian Hemisphere.

The rise and fall of nations has been a feature of both nation states and civilisations. China’s relative power is growing day by day. The ultimate aim of every great power is to maximize its share of world power and eventually dominate the system. Dominating Asia or the South China Sea is not only beneficial for the survival of China, but it will demonstrate Beijing’s foreign policy capability. In preserving its strategic interests China cannot be regarded as acting irrationally, it is simply the strategic behaviour of a rising power. Similarly, the US’ stand against China is strategically rational behaviour too. It is plausible for the US to accommodate China peacefully, rather than to challenge it globally. Endangering China’s strategic interests in Asia might be risky. India too will endanger itself by collaborating with the US for taming China. Both China and India should collaborate with each other for the betterment of the region. However, China will not allow India to stand against its rising prominence. Regional hegemony is not enough to control the Hemisphere, dominance is important (Mearsheimer, 2014). China is trying to dominate the Asian hemisphere the way the US dominates the Western Hemisphere. For survival, dominance offers the way under international anarchy, as Mearsheimer (2014) has claimed. China is now powerful and it is logical for it to settle disputes on its own terms.

Conclusion

Beijing’s aggressiveness may escalate in the case that the US becomes increasingly provocative, or in its passing of the buck to India in order to tame China at the extreme level. Beijing is pushing Washington out of the Asia-Pacific region as the US pushed the European great powers out of the Western Hemisphere in the 19th century with the Monroe Doctrine. Logically, for China, the US has no right to interfere in disputes over the maritime boundaries of the South China sea. Thus, the American century is coming to its end and China is ready to dominate the Asian Hemisphere. A corollary to this, India (as a lesser power) might ally with other states to balance against China. However, to reduce the chances of war, Beijing’s rise should not be identified as a threat. China’s labelling as a threat to world peace and security is contested. To cite Douglas Gibler (2007), in order to end the incidences of war in the Asian Hemisphere, territorial settlement treaties, not alliances, might be effective.

No comments:

Post a Comment