By Ronald U. Mendoza and Dion L. Romano

In a move that surprised many, in early June 2020 amid the Philippines’ COVID-19 pandemic challenges, President Rodrigo Duterte certified as “urgent” the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020. In just a matter of days, the House of Representatives dispensed with any further review process and accepted the Senate version of the bill, then promptly sent it to the president for signature. On July 3, Duterte signed this bill into law, notwithstanding calls for him to veto it.

In a move that surprised many, in early June 2020 amid the Philippines’ COVID-19 pandemic challenges, President Rodrigo Duterte certified as “urgent” the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020. In just a matter of days, the House of Representatives dispensed with any further review process and accepted the Senate version of the bill, then promptly sent it to the president for signature. On July 3, Duterte signed this bill into law, notwithstanding calls for him to veto it.

Early on, the bill generated extensive backlash and critique from different sectors across youth groups, academia, church, business, and civil society. Critics had a number of objections: ill timing; credibility issues among the implementing agencies; the risk of abuse; and potentially unconstitutional provisions. The law created division when it should have unified the country against the rising threat of terrorism. This article provides a sober review of terrorism issues in the Philippines, and hopefully helps promote a better understanding toward a unified way forward.

Terrorism Risk in the Philippines Is Real and Increasing

In the Philippines, the terrorist threat has taken a bloody evolution — from killings, kidnappings, and armed attacks in the past, to increased use of improvised explosive devices in the last decade, and more recently in the last few years a deadly ramp up of suicide bombings. Between July 2018 and November 2019, there were six suicide bombings in the country, with evidence that further waves of bombings were set to take place but were foiled. Attacks include:

July 2018: A suicide bomber, believe to be a Moroccan, detonated his explosives inside his vehicle at a government checkpoint in Basilan, killing 10.

January 2019: An Indonesian couple, who had tried to enter Syria but were deported by Turkish authorities, blew themselves up at a cathedral in the southern Philippine town of Jolo, killing 23 and wounding more than 100 during a Sunday Mass.

June 2019: Two men – the first Filipino bombers – detonated their explosives outside an army camp in Sulu, killing five, including themselves, and wounding 22 others.

September 2019: A woman, believed to be an Egyptian, blew herself up at the gate of a military base in Jolo, though causing no further casualties.

November 2019: Suspected suicide bombers were foiled by government forces. Two of the three suspected would-be bombers are believed to be the Egyptian bomber’s husband and their son.

The suicide attacks were all in the Sulu archipelago, Abu Sayyaf’s stronghold, and were all claimed by the Islamic State. Home-grown terrorists in the Philippines seeking to align with IS, attempted to take Marawi city in May 2017, provoking a five-month siege, and inspired foreign fighters to join the fight. Delays in rebuilding Marawi city and returning residents to their properties and homes have raised concerns that terror groups are using this to recruit among highly disgruntled residents.

Based on reports by both the media and the Armed Forces of the Philippines, the first Filipino suicide bombing took place in June 2019. This is a watershed moment in the country, since it signals an extreme form of radicalizing home-grown terrorists.

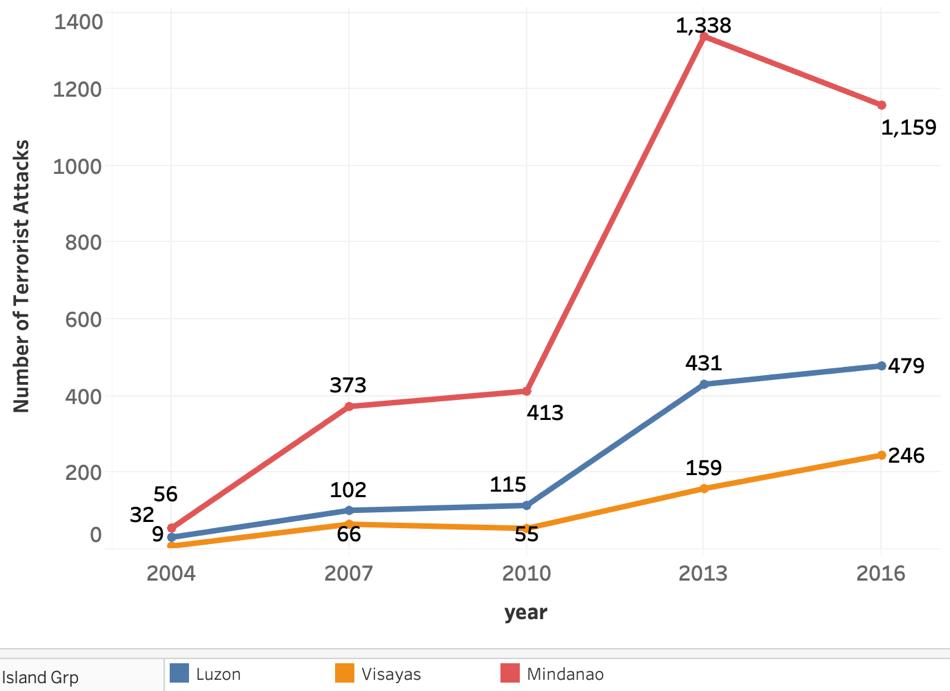

Drawing on data compiled by the University of Maryland, an analysis of trends in terror attacks in the Philippines reveals a large spike particularly in Mindanao between 2010 and 2016. The Global Terrorism Database of the University of Maryland compiles information for each attack event; the database logs different variables such as location, success of the attack, involvement of weapons or explosives, and number of casualties. Figure 1 reveals how the number of terror attacks in the Philippines has increased over the past five election terms, especially in Mindanao. Weak border control, bad governance, and historic injustices and festering inequality are some of the factors security analysts and scholars emphasize in terms of exacerbating conditions for terrorism.

Figure 1: Number of terrorist attacks per election term per major island group. Data from the UM Global Terrorism Database.

Counterterrorism Legislation Is Only Part of the Problem; Reforming National Security Institutions Will Be Key

It bears stressing that the Philippines has already enacted a law precisely intended to curb and prevent acts of terrorism. Republic Act No. 9731, also known as the Human Security Act (HSA) of 2007, came into force in July 2007 to help the government and law enforcement agencies address the threat of terrorism. Nevertheless, security analysts note that the HSA of 2007 has never been fully utilized, having been implemented only twice since its enactment — the first time was to proscribe the Abu Sayyaf Group as a terrorist organization, while the second was against a person who was involved in the Marawi siege (the case was eventually settled out of court). Some analysts claim that the HAS of 2007 contains many safeguards that effectively tie the hands of counterterrorism officers (including high penalties for mistaken arrests). These same safeguards appear to have been removed in the present anti-terrorism bill, in an effort to give authorities more leash to pursue terror suspects.

In addition, the definition of terrorism has been seemingly expanded, providing for an ambiguous and overbroad definition of what qualifies as terrorism, making it susceptible to various interpretations, and to government’s abuse of authority. As retired Associate Justice Vicente V. Mendoza puts it, “A statute whose terms are so vague that persons of common understanding must necessarily guess at its meaning or differ as to its application offends due process. And a statute that sweeps unnecessarily broadly both and protected conduct is overbroad and likewise offends due process.”

The balance of power and the discretion on its use has been enhanced by the present anti-terrorism act. Will it be used with a high degree of discipline and accountability? The country’s national security agencies still face lingering credibility and trust issues, underscoring the need to support reformists in these organizations to ramp up professionalization and capacity-building and advanced training. The proponents of the anti-terrorism act are working on the presumption that the current institutions – the whole gamut of the security, executive, and judicial institutions – would give high regard to human rights and would exercise a robust degree of accountability. However, the public reaction against the proposed law could be inferred as a manifestation of diminished trust in key government institutions tasked with anti-terrorism efforts.

The abuses committed by some police during the bloody war against illegal drugs, the serious records of extrajudicial killings permeating some parts of the country, the controversial red-tagging practiced by some government agents, even of legitimate organizations, and the lingering concerns over human rights violations across various administrations are some of the serious factors that affect people’s trust toward the government. More recently, the killing of four intelligence officers of the Armed Forces of the Philippines at a Philippine National Police checkpoint in Jolo, Sulu by PNP personnel raises the specter of abuse even more. These issues are rather fundamental, and an already doubtful public has only been rewarded with even more cause for concern over the government’s readiness for this amount of power and discretion.

Inequality, Injustice, and Impunity Could Increase the Risk of Terrorism; Hence Real Solutions Go Well Beyond Police and Military Ones

As a final note, international and some domestic research on the roots of terrorism emphasize the need to understand its deep roots in society and what exactly contributes to radicalization of this degree. Researchers from the University of Freiburg examined data on terrorist attacks in 113 industrial and developing countries during the period from 1984-2012. They find strong empirical evidence that the level of income inequality is associated with more domestic terrorism. They analyzed the underlying transmission channels, arguing that this link could be due to the ill effects of income inequality on institutional outcomes (e.g. corruption). The latter, in turn, motivates domestic terrorism. Rapid and inclusive economic development coupled with strong redistribution are seen to lower terrorism risks, while also providing an environment which is much more resilient to terrorist influence.

A clear and holistic strategy against terrorism clearly requires far more than any law focused on police and military action. Australian National University counterterrorism scholar Professor Jacinta Carroll probably framed it best: “Terrorists of all types use propaganda as their main weapon, but their words and actions can only take root in fertile soil.”

Ronald U. Mendoza is Dean at Ateneo de Manila University’s School of Government.

Dion L. Romano is Project Manager of Ateneo Policy Center, Ateneo School of Government.

This article draws from a recent paper reviewing counterterrorism issues in the Philippines. Mendoza, Ronald U. and Ong, Rommel Jude and Romano, Dion Lorenz, “Counter-Terrorism in the Philippines: Review of Key Issues” (July 3, 2020).

No comments:

Post a Comment