By SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR.

WASHINGTON: Despite some very public blow-ups, “we have had overwhelming support and interest from tech industry in working with the JAIC and the DoD,” the new acting director of the Joint Artificial Intelligence Center, Nand Mulchandani, said Wednesday in his first-ever Pentagon press conference. Speaking two years after Google very publicly pulled out of the AI-driven Project Maven, Mulchandani said that, today, “[we] have commercial contracts and work going on with all of the major tech and AI companies — including Google — and many others.”

Nand Mulchandani

Mulchandani is probably better positioned to sell this message than his predecessor, Lt. Gen. Jack Shanahan, an Air Force three-star who ran Project Maven and then founded the Joint AI Center in 2018. While highly respected in the Pentagon, Shanahan’s time on Maven and his decades in uniform created some static in Silicon Valley. Mulchandani, by contrast, has spent his life in the tech sector, joining JAIC just last year after a quarter-century in business and academe.

But relations with the tech world are still tricky at a time when the two-year-old JAIC is moving from relatively uncontroversial uses of artificial intelligence such as AI-driven predictive maintenance, disaster relief and COVID response, to battlefield uses. In June, it awarded consulting firm Booz Allen Hamilton a multi-year contract to support its Joint Warfighting National Mission Initiative, with a maximum value of $800 million, several times the JAIC’s annual budget. For the current fiscal year, Mulchandani said, “spending on joint warfighting is roughly greater than the combined spending on all the of other JAIC mission initiatives” combined.

Lt. Gen. Jack Shanahan

But tech firms should not have a problem with that, Mulchandani said, and most of them don’t, because AI in the US military is governed far more strictly by rivals like China or Russia. “Warfighting” doesn’t mean Terminators, SkyNet, or other scifi-style killer robots. It means algorithmically sorting through masses of data to help human warfighters make better decisions faster.

But tech firms should not have a problem with that, Mulchandani said, and most of them don’t, because AI in the US military is governed far more strictly by rivals like China or Russia. “Warfighting” doesn’t mean Terminators, SkyNet, or other scifi-style killer robots. It means algorithmically sorting through masses of data to help human warfighters make better decisions faster.

Wait, one reporter asked, didn’t Shanahan say shortly before his retirement that the military was about to field-test its first “lethal” AI?

“Many of the products we work on will go into weapons systems,” Mulchandani said. “None of them right now are going to be autonomous weapons systems.”

“Now, we do have products going on under joint warfighting which are actually going into testing,” he went on. “As we pivot [to] joint warfighting, that is probably the flagship product … but it will involve operators, human in the loop, human control.”

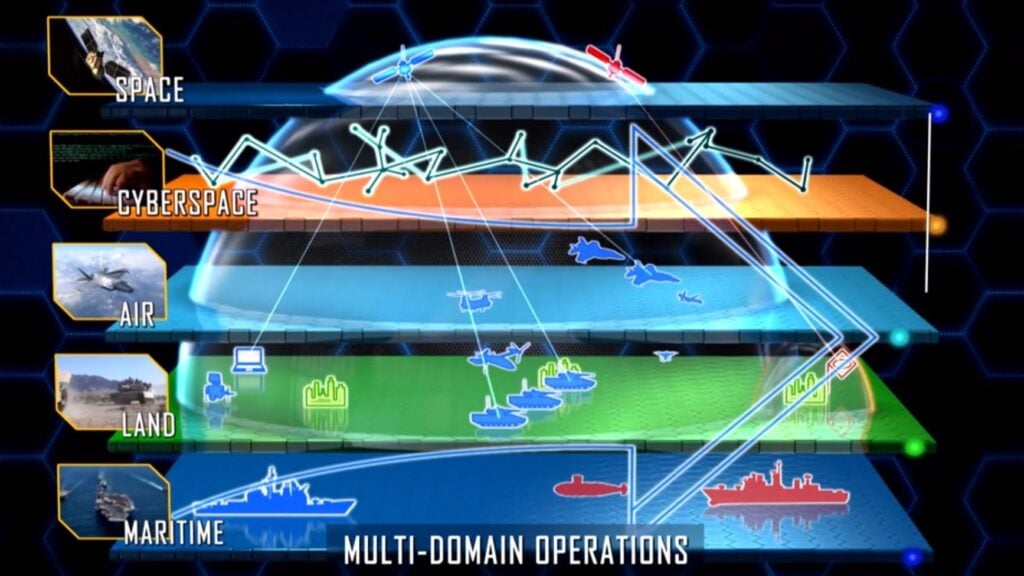

For example, JAIC is working with the Army’s PEO-C3T (Command, Control, & Communications – Tactical) and the Marine Corps Warfighting Lab (MCWL) on a Fire Support Cognitive Assistant, software to sort through incoming communications such as calls for artillery or air support. It’s part of a much wider push, led by the Air Force, to create a Joint All-Domain Command & Control (JADC2) mega-network that can coordinate operations by all five armed services across land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace.

Multi-Domain Operations, or All Domain Operations, envisions a new collaboration across land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace (Army graphic)

“Since the Department has repeatedly demonstrated its willingness to disregard congressionally mandated reprogramming procedures, the Committee cannot agree to provide the additional budget flexibility the Air Force requested,” the 2021 spending bill says.

That’s “lethal” in the buzzwordy way the modern Pentagon uses the term, since it contributes to combat effectiveness. But the AI isn’t pulling the trigger, Mulchandani emphasized. The whole point of a “cognitive assistant,” he said, is “there’s still a human sitting in front of a screen who’s actually being assisted.”

True, this kind of AI can help commanders pick targets for lethal strikes. That was an aspect of Project Maven that particularly upset some at Google and elsewhere.

But there’s a crucial difference. Maven used AI to analyze surveillance feeds and track potential targets, pushing the limits of object-recognition technology that Mulchandani said is still not ready for use on a large scale. For much of the current crop of warfighting AI, by contrast, the central technology is Natural Language Processing: in essence, teaching algorithms – whose native tongue is 1s and 0s – how to make sense of normal, unstructured writing, Online advertisers have invested heavily in NLP, driving rapid progress.

“With the Cognitive Fires Assistant, the core technology there is NLP,” Mulchandani said. While modern command posts do use computers to coordinate calls for artillery and air support, it’s not an automated process. If you look over a targeteer’s shoulder at their screen, “there’s literally 10 to 15 different chat windows all moving at the same time,” he said. “So we’re applying NLP technology to a lot of that information” to help condense it, structure it and highlight the most important items.

In fact, Mulchandani said, the military is full of complex, rigidly structured and exhaustively documented processes that are a natural fit for automation. The armed forces long ago figured out how to train young humans to do things the same way every time. Instead of making humans act like robots, why not train machine-learning algorithms to do the grunt work instead? After all, modern weapons systems and command posts already rely on large amounts of software – it’s just not particularly smart software.

“All of these systems are running on software and hardware systems today,” Mulchandani said. “What we’re doing with AI is either making them more efficient, making them faster …making them more accurate … reducing overload.

“There’s nothing magic that we’re really doing here, other than applying AI to already existing processes or systems,” he said.

Campaign to Stop Killer Robots graphic

Of course, the military’s existing processes and systems tend to involve coercion and deadly force, which makes privacy advocates and peace activists skeptical of much the Pentagon does, AI-enabled or not. But Mulchandani argues that the US Department of Defense operates under strict ethical guidelines. For example, DoD can’t touch surveillance data on US citizens, and the JAIC is not investing in any kind of facial recognition technology.

The longstanding regulation here is DoD 3000.09, which sets up an elaborate review process for any automated system that might lead to loss of human life – although, contrary to conventional wisdom, Pentagon policy doesn’t outright ban automated killing machines. This year, Defense Secretary Mark Esper formally adopted a set of ethical principles for military AI, which the JAIC is already writing into contracts, including the $800 million one for joint warfighting – although the principles are not yet legally binding. The JAIC itself has an in-house ethics team headed by a professional ethicist, and, just as important, a testing team to make sure the software actually performs as intended.

China and Russia are not taking those precautions, Mulchandani warned. That doesn’t mean they’re getting ahead of the US in AI writ large, he argued. “There are some areas where China’s military and police authorities undeniably have the world’s advanced capabilities, such as unregulated facial recognition for universal surveillance… and Chinese language text analysis for internet and media censorship,” Mulchandani said. “We simply don’t invest in building such universal surveillance and censorship systems.”

However, “for the specific national security applications where we believe AI will make a significant impact,” he said, “I believe the United States is not only leading the world, but is taking many of the steps needed to preserve US military advantage over the long term – as evidenced.. by what we’re doing here at JAIC.”

No comments:

Post a Comment