by Eleanor Albert and Lindsay Maizland

Hong Kong is a special administrative region of the People’s Republic of China that, unlike the mainland’s provinces, has certain political and economic freedoms. The former British colony is a global financial capital that has historically thrived off its proximity to China.

Hong Kong is a special administrative region of the People’s Republic of China that, unlike the mainland’s provinces, has certain political and economic freedoms. The former British colony is a global financial capital that has historically thrived off its proximity to China.

But in recent years, many in Hong Kong have become concerned with intensifying economic inequality and Beijing’s efforts to encroach on the city’s political system, which sparked massive protests in 2019. As China’s economic and military might grow, some fear that Hong Kong’s significant autonomy could erode. Beijing’s passage of a new national security law in June 2020 heightened fears of its tightening grip over Hong Kong.

What is Hong Kong’s political status?

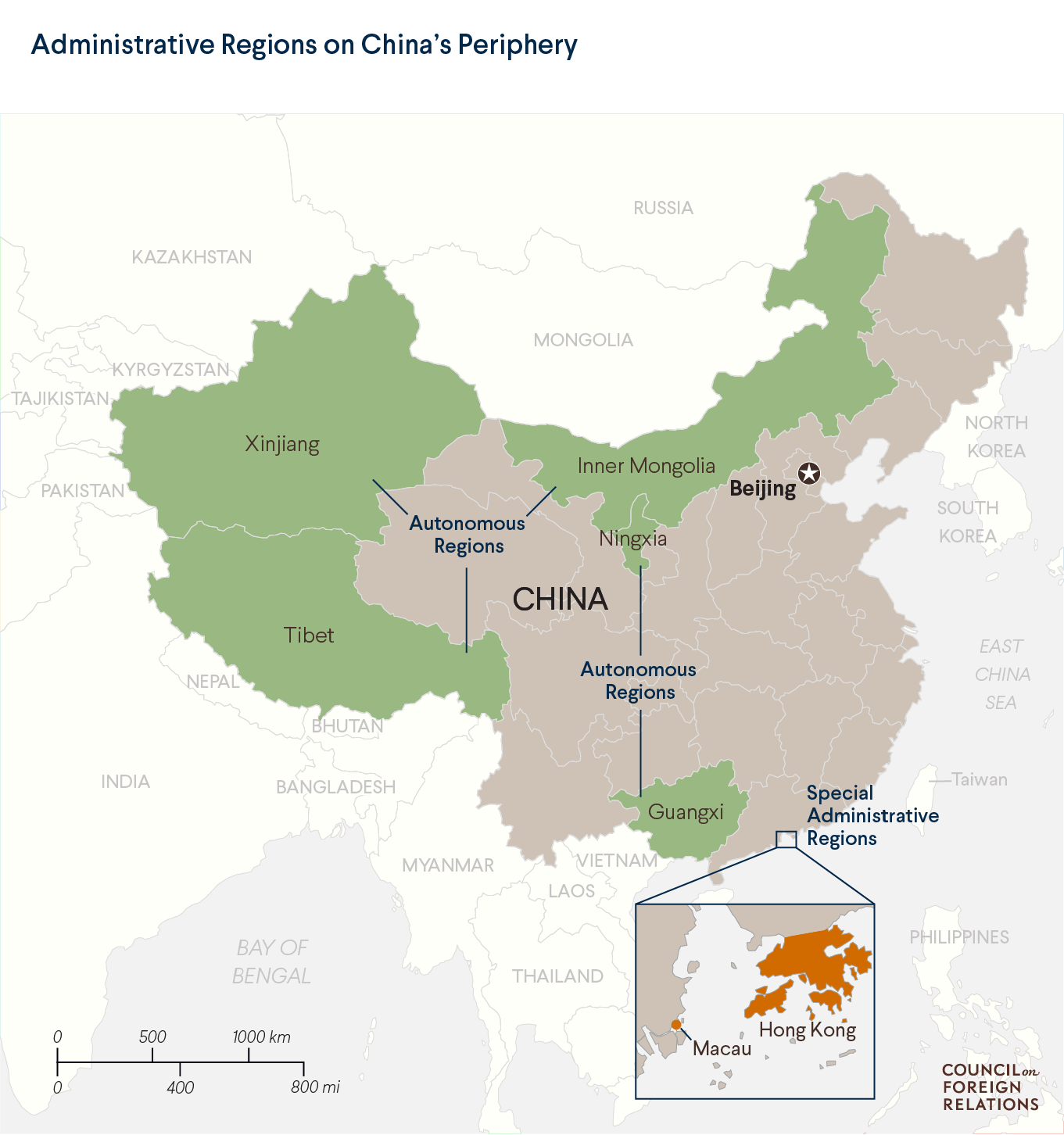

In recent decades, Hong Kong has been largely free to manage its own affairs based on “one country, two systems,” a national unification policy developed by Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s. The concept was intended to help reintegrate Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau with sovereign China while preserving their unique political and economic systems. After more than a century and a half of colonial rule, the British government returned Hong Kong in 1997. (Qing Dynasty leaders ceded Hong Kong Island to the British Crown in 1842 after China’s defeat in the First Opium War.) Portugal returned Macau in 1999, and Taiwan remains independent.

The Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984 dictated the terms under which Hong Kong was returned to China. The declaration and Hong Kong’s Basic Law, the city’s constitutional document, enshrine the city’s “capitalist system and way of life” and grant it “a high degree of autonomy,” including executive, legislative, and independent judicial powers for fifty years (until 2047). Chinese Communist Party officials do not preside over Hong Kong as they do over mainland provinces and municipalities, but Beijing still exerts considerable influence through loyalists who dominate the region’s political sphere. Beijing also maintains the authority to interpret Hong Kong’s Basic Law, a power that it has only used a handful of times since the handover. Under the law, Hong Kongers are also guaranteed freedoms of the press, expression, assembly, and religion, but in practice Beijing has grown less tolerant of criticism. Hong Kong is allowed to forge external relations in certain areas—including trade, communications, tourism, and culture—but Beijing maintains control over the region’s diplomacy and defense.

Beijing moved to rework the “one country, two systems” framework and undermine Hong Kong’s freedoms in 2020. The National People’s Congress Standing Committee, an arm of the PRC’s legislative body, passed a national security law in June that would effectively criminalize any dissent in Hong Kong. The full text of the law, only released the day it went into effect, defines crimes such as terrorism, subversion, secession, and collusion with foreign powers extremely broadly, which critics say could help crack down on protesters. It also allows Beijing to establish a security force in Hong Kong and appoint judges to hear national security cases. In a break from usual legal processes, the law bypassed the Hong Kong legislature. Pro-democracy activists and lawmakers decried the move and expressed fears that it could be “the end of Hong Kong.”

Several countries, such as Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, and the European Union criticized the move and warned of potential measures in response. The Donald J. Trump administration said it would impose visa restrictions on Chinese officials undermining Hong Kong’s autonomy, restrict exports of defense equipment to Hong Kong, and start revoking its favorable trading status.

What is Hong Kong’s economic connection to the mainland?

A metropolis of more than seven million people, Hong Kong is a global financial and shipping center that has prospered from its proximity to the world’s second-largest economy. It ranks second in the world in trade as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), with services accounting for more than 90 percent of its economy. Relatively low taxes, a highly developed financial system, light regulation, and other capitalist features make Hong Kong one of the world’s most attractive markets and set it apart from mainland financial hubs such as Shanghai and Shenzhen. Hong Kong continues to rank highly in economic competitiveness reports, placing third in the World Bank’s annual Doing Business rankings and second in the world on the Heritage Foundation’s 2020 Index of Economic Freedom. Most of the world’s major banks and multinational firms maintain regional headquarters in the city.

But Hong Kong’s economic power has diminished significantly relative to the mainland—its GDP fell from 16 percent of China’s after the handover in 1997 to less than 3 percent in 2017. Commercial ties between the two neighbors remain tight. Hong Kong is China’s third-largest trading partner (after the United States and Japan), accounting for about 6 percent of China’s total trade in 2019. The city is also China’s largest source of foreign direct investment (FDI) and a place where Chinese firms raise vast amounts of offshore capital.

At the same time, Hong Kong relies heavily on the mainland. China, the top destination for Hong Kong exports, accounted for more than half of the city’s total trade in 2019. More than half of the mainland’s outward FDI stock is destined for Hong Kong, though much of this investment is later channeled overseas.

What are the political tensions between Hong Kong and Beijing?

As a one-party state, China is reluctant to allow Hong Kong to develop into a full-fledged democracy with free and fair elections. Experts say that ambiguity in the Basic Law heightens this fundamental tension. The document states that the “ultimate aim” is to have Hong Kong’s leader elected by a popular vote, but it does not give a deadline for these reforms to occur.

Since the handover, an election committee composed of representatives from Hong Kong’s main professional sectors [PDF] has selected chief executives. Today, these 1,200 members come from a range of societal groupings: the industrial, commercial, and financial sectors; other professional sectors, including higher education and engineering; labor, social service, and religious groups; and Hong Kong political bodies. All changes to political processes have to be approved by the Hong Kong government and China’s National People’s Congress.

Some analysts say China’s repeated decision to put off further political reforms, including a national vote for chief executive, indicate that Beijing will drag its feet indefinitely. In the most recent election, only candidates vetted by a nominating committee chosen by Beijing were allowed to run. Carrie Lam, viewed as an establishment candidate, won the 2017 race, becoming Hong Kong’s first female chief executive.

Beijing increased its efforts to rein in political dissent following massive protests in 2014, known as the Umbrella Movement, and the electoral victories of pro-democracy factions in 2016. Later that year, a controversy erupted when several new legislators modified their oaths of office while being sworn in, prompting Beijing to intervene in local court proceedings and pass a new interpretation of Hong Kong’s Basic Law that outlined consequences for legislators who deviated from the oath. Ultimately, six legislators were disqualified.

View Slideshow

In recent years, mainland officials have also used Hong Kong media to push Beijing’s narrative and clamp down on critical voices. Sino United Publishing, a company reportedly owned by the Chinese government, controls as much as 70 percent of the local market. Mysterious disappearances of a handful of Hong Kong booksellers, media executives, and a Chinese billionaire have heightened concerns about Beijing’s creeping control over Hong Kong.

Tensions with Beijing came to the fore again in the summer of 2019, when hundreds of thousands of people protested against a legislative proposal that would have allowed extraditions to mainland China. The protests continued for months, with demonstrators storming the Legislative Council building in July and occupying Hong Kong International Airport the following month, as they morphed into a battle over Beijing’s deepening control of the city. Reports of police brutality, including excessive use of tear gas and rubber bullets, exacerbated tensions. Lam withdrew the Beijing-endorsed bill in September, but protesters continued to demand electoral reforms and an independent investigation into police violence.

As the protests stalled amid the coronavirus pandemic in early 2020, the Hong Kong government moved to clamp down on the pro-democracy movement. It banned gatherings of more than four people, saying anyone who held such gatherings could be jailed for up to six months. In April, it arrested fifteen activists and former lawmakers, which reignited protests despite the extension of coronavirus restrictions. The passage of the national security law in June, which Chinese officials and pro-Beijing lawmakers said was necessary to restore stability following the massive protests, silenced many Hong Kong residents who had fought for democracy.

What do Hong Kongers want?

The majority of Hong Kongers support the maintenance of “one country, two systems.” Public opinion polling has found that a minority—just 11 percent of people in 2017—supported or strongly supported the idea of an independent Hong Kong [PDF] after 2047.

The widening generational gap and mounting economic inequality have intensified political divisions.

However, their confidence in the arrangement may be waning. Other public opinion surveys indicate that Hong Kong residents are increasingly dissatisfied with the Hong Kong government and the state of politics. Amid the extradition bill protests, dissatisfaction with the Hong Kong government skyrocketed, with 81 percent of respondents to a University of Hong Kong poll expressing negative opinions in June 2019, up from around half earlier in the year. A widening generational gap and mounting economic inequality—Hong Kong has one of the world’s highest levels of income inequality—have deepened political divisions. Younger generations feel they are not reaping the benefits of their city’s wealth and face stiff competition from an influx of mainlanders. The influence of mainland money also widens the divide between socioeconomic classes.

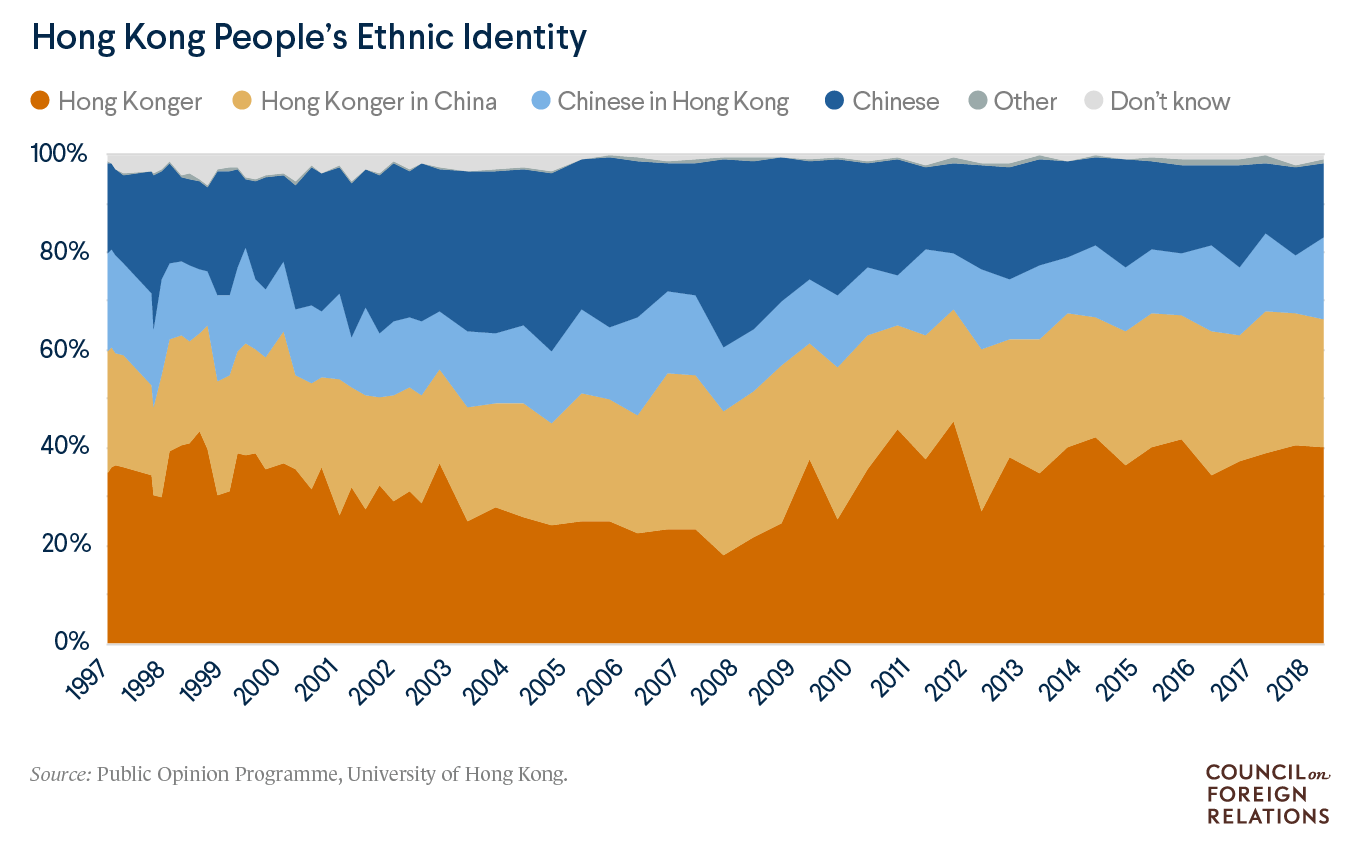

The ethnic identity of the city has also evolved since its handover to China. Though many still describe themselves as having a mixed identity, more and more people see themselves as Hong Kongers or Hong Kongers in China, while the number of those who identify as Chinese or Chinese in Hong Kong has dropped.

What’s the political balance in Hong Kong?

The political scene has traditionally been split between two factions: pan-democrats, who call for incremental democratic reforms, and pro-establishment groups, who are by and large pro-business supporters of Beijing. The pro-establishment forces have typically been more dominant in Hong Kong politics. Pan-democrats recognize that Hong Kong cannot force Beijing into reforms that could jeopardize its central authority and that reforms are more likely to succeed when they are mutually beneficial.

At the same time, there is a rising movement of student protesters demanding a more democratic system. After the 2014 protests, young activists formed new political groups and parties embracing a more overtly local, Hong Kong identity. These parties include more radical, anti-Beijing parties, such as Youngspiration and Hong Kong Indigenous, and Demosisto, a party advocating for greater autonomy and self-determination. However, following Beijing’s passage of the national security law in 2020, Demosisto and several other opposition groups disbanded.

What are Beijing’s plans for Hong Kong?

It’s unclear what China’s plans are for Hong Kong after 2047. For now, Beijing wants to maintain its territorial integrity and therefore views all protests and pro-democracy political voices as potential challenges to its one-party rule. It perceives Hong Kong’s calls for democracy as particularly threatening because of the city’s international prominence and the dangerous precedent that any compromise on political reform could set for China’s other regions, including Tibet, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, Macau, and Taiwan.

Beijing views all protests and pro-democracy political voices as potential challenges to China’s one-party rule.

In recent years, Beijing has sharpened its rhetoric. On a trip to Hong Kong in 2017 to commemorate the twentieth anniversary of the British handover, President Xi Jinping issued a stark warning that “any attempt to endanger China’s sovereignty and security” or to challenge Beijing’s power would cross a red line.

In 2017, Beijing announced the Greater Bay Area project, an ambitious plan to integrate Hong Kong and cities in neighboring Guangdong Province into a more cohesive region, one that could rival the San Francisco Bay or Tokyo Bay areas and drive future innovation and development. Echoing the connectivity narrative of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the Greater Bay would constitute a population of more than seventy million people and a $1.5 trillion economy.

Over the past few years, China has moved to connect Hong Kong more to the mainland with the opening of a high-speed rail station and a thirty-six-kilometer (twenty-two-mile) bridge linking Hong Kong and Macau to the mainland city of Zhuhai. Some critics say the efforts may diminish Hong Kong’s special standing. “‘Connectivity’ might be one of the keywords of China’s discourse, but all the infrastructure built over the past few years in neighboring cities has only helped to dilute Hong Kong further into a vast economic zone where it is no longer the center,” writes Philippe le Corre of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

* A previous version of the above map mislabeled Hong Kong and Macau as autonomous regions and Guangxi, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Tibet, and Xinjiang as special administrative regions.

No comments:

Post a Comment