India has become an important trading partner for the United States over the past two decades, but the relationship has been marred by long-standing disagreements on everything from dairy products to intellectual property rights protections.

India has become an important trading partner for the United States over the past two decades, but the relationship has been marred by long-standing disagreements on everything from dairy products to intellectual property rights protections.

Trade between the United States and India has grown steadily ever since India’s economy began to take off in the mid-1990s and its information technology sector shot to prominence in the early 2000s. From 1999 to 2018, trade in goods and services between the two countries surged from $16 billion to $142 billion. India is now the United States’ eighth-largest trading partner in goods and services and is among the world’s largest economies. India’s trade with the United States now resembles, in terms of volume, U.S. trade with South Korea ($167 billion in 2018) or France ($129 billion).

But as trade between Washington and New Delhi has increased, so too have tensions. U.S. and Indian officials have disagreed for years on tariffs and foreign investment limitations, but also on other complicated issues, particularly within agricultural trade. Concern for intellectual property rights has preoccupied the United States for thirty years, while issues concerning medical devices and the fast-growing digital economy have more recently emerged. On top of this, the Donald J. Trump administration has exacerbated tensions by creating new dilemmas, including a focus on bilateral trade deficits and the application of fresh tariffs, prompting retaliation from Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government.

This guide highlights eight ongoing trade issues between the United States and India that will be worth watching as diplomacy intensifies.

The Trump administration’s approach to trade resulted in three new areas of friction that had not previously been on the already extensive menu of economic tensions with India.

The World This Week

A weekly digest of the latest from CFR on the biggest foreign policy stories of the week, featuring briefs, opinions, and explainers. Every Friday.

Bilateral trade deficits. Previously not a top U.S. trade concern, these became a major focus when Trump issued an executive order in 2017 requiring a study of the United States’ most significant trade deficits. India has slightly narrowed the trade deficit in goods with the United States, which went from $24.3 billion in 2016, the tenth-largest that year, to $23.3 billion in 2019, the eleventh-largest. Indian negotiators have proposed reducing the deficit via major purchases of products including liquefied natural gas and aircraft.

Tariffs. The Trump administration began applying new tariffs in 2018 on steel and aluminum imports from dozens of countries, including India, using a national security exemption in U.S. trade law. In response, New Delhi drew up a list of retaliatory tariffs and filed it with the World Trade Organization (WTO), but held off on applying them.

Generalized System of Preferences (GSP). Following a public review process, the Trump administration removed India from the GSP program, a special trade treatment for developing countries. One qualification of the program is “equitable and reasonable” access to that country’s markets for U.S. goods and services, and the administration noted still-significant trade barriers in India. Shortly after the Trump administration pulled India from the GSP, India pulled the trigger on its retaliatory tariffs, after which the United States filed a dispute at the WTO. These retaliatory tariffs remain in place.

Agricultural Products

Although agricultural products are not the largest component of U.S.-India trade, tensions over them are long-standing and remain among the most difficult to resolve. The United States exported around $1.5 billion worth of agricultural products to India in 2018 and imported $2.7 billion. Exports to India include fruit, nuts, legumes, cotton, and dairy products, which are important to the economies of California, Montana, and Washington. Spices, rice, and essential oils are the top agricultural items imported from India to the United States.

A farmer holds chickpeas on a farm near Choteau, Montana. Todd Klassy

India’s 2019 retaliatory tariffs included U.S. almonds, walnuts, cashews, apples, chickpeas, wheat, and peas—and came on top of globally applied tariff hikes by New Delhi. India imposed a retaliatory tariff of 20 percent on in-shell walnuts, added to a 2018 global duty hike to 100 percent. U.S. in-shell walnuts now carry a duty of more than 120 percent in India, according to the California Walnut Board and Commission. Apples, an iconic product of Washington State, were hit with a 20 percent tariff, on top of an existing 50 percent duty for all countries. Tariffs on in-shell almonds went from 35 rupees per kilogram to 41 rupees (from about 50 to 60 cents), with the tariff determined by weight rather than value. India is the largest market for California almonds, accounting for about $600 million in 2018 exports according to the California Almond Board. Chickpeas, of which India is one of the world’s largest buyers, were hit with [PDF] a 10 percent tariff on top of a 2017 globally applied tariff of 60 percent. The USA Dry Pea & Lentil Council described pulse exports as “devastated” by trade wars underway since 2017.

Negotiations over U.S. dairy products have gone on for years. It is difficult for U.S. dairy farmers to sell their products in India, according to the International Dairy Foods Association [PDF], because India requires that dairy products are “derived from a dairy cow that has been fed a vegetarian diet for its entire life.” India defends its position on religious and cultural grounds, whereas the association calls these requirements “scientifically unwarranted.”

India rejected U.S. proposals [PDF] (p. 241) in 2015 and 2018 for consumer labels indicating the diet of dairy animals. Frustrated, the National Milk Producers Federation and the U.S. Dairy Export Council sought India’s removal from the GSP program.

Intellectual Property Rights

Intellectual property rights in India have been a chief U.S. concern since at least 1989, the year of the first “Special 301 report” mandated by Congress to identify intellectual property issues in trade. Concerns include piracy of software, film, and music and weak patent protections, among others. In that first report, India was one of eight countries placed on a priority watch list [PDF].

India has remained on the watch list, despite some progress. To comply with its obligations as part of the WTO’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, India amended its patent act [PDF] to recognize product rather than process patents, meaning that replicating a product using a different process would qualify as an infringement. This came into force in 2005. However, the United States has sought further improvements. By 2018, Washington still cited [PDF] insufficient patent protections, restrictive standards for patents, and threats of compulsory licensing. Other U.S. concerns include India’s copyright regime and whether current approaches can deliver “pro-innovation and -creativity growth policies.”

Investment Barriers

India has limited foreign investment in sectors such as insurance and banking for decades. While India has substantially liberalized [PDF] foreign direct investment (FDI) procedures, issues remain [PDF]. The insurance industry has an FDI limit of 49 percent and a requirement that companies be Indian-controlled. In banking, foreign ownership is capped at 74 percent. Media also face foreign investment limits: 49 percent for cable television, 26 percent for FM radio, 74 percent for direct-to-home satellite broadcasting, 49 percent for television news, and 26 percent for print newspapers and periodicals.

In single-brand retail, which comprises companies such as Nike that sell only their own goods, Indian rules permit 100 percent FDI but have some local sourcing requirements. Multi-brand retail is permitted up to 51 percent FDI, however Indian states can opt in or opt out of allowing this type of foreign investment; currently, only around nine of India’s twenty-nine states permit it (plus a small union territory). Additional requirements for multi-brand include at least $100 million in infrastructure investment, as well as local sourcing conditions.

These are just a few sectors that illustrate the complexity and density of the limitations to foreign services operating in India. Reflecting the continued importance of investment, the U.S.-India Strategic Policy Forum [PDF] and the U.S.-India Business Council have prioritized the removal of investment limits as a chief policy issue.

Harley-Davidson Motorcycles

President Trump has often bemoaned India’s high tariffs on motorcycles—they stand at 50 percent for some Harley-Davidson models. However, Trump is not the first U.S. president to focus on market access for America’s iconic bike. In 2007, during the George W. Bush administration, trade negotiators agreed to a deal under which Harley-Davidsons would be able to enter India in exchange for Indian mangoes gaining access to the U.S. market.

An Indian owner of a Harley Davidson motorcycle takes part in a bike rally in Bangalore. Manjunath Kiran/Getty Images

However, the mangoes-for-motorcycles deal wasn’t about tariffs, and instead worked through issues over emissions regulations and a pest-control irradiation process for mangoes in India to open up new trade.

It turned out that high Indian duties on large-engine motorcycles made Harleys too expensive for Indian consumers. To make the bikes more affordable, Harley-Davidson built an assembly plant in India for less expensive models, which were imported unassembled and subject to much lower duties. The managing director for Harley-Davidson India told CNN at the time that assembly in India would bring down duties by around 40 percent.

When Trump raised the issue of India’s motorcycle duties in 2017, tariffs were at 75 percent for the largest engine imports. Harley-Davidson sold fewer than 3,700 units in India that year, and most were cheaper models assembled in India. The tariffs on these more expensive, larger motorcycles fell to 50 percent after Trump discussed the issue with Modi in 2018, but Trump has said that 50 percent is “still unacceptable.”

Medical Devices

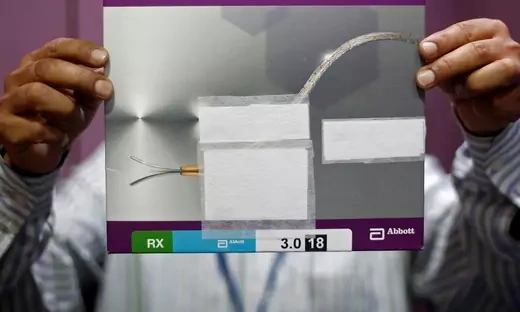

The Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) expressed concern for years about customs duties on medical equipment and devices, and tensions were exacerbated in 2017 when the Indian government applied new price controls on coronary stents and knee implants.

A staff member shows a heart stent inside a store at a New Delhi hospital. Adnan Abidi/Reuters

The following year, USTR explained the impact of the price controls in its National Trade Estimate report [PDF] (p.235). U.S. manufacturers sought permission from the Indian regulatory authority to pull these devices from the market but were denied, forcing U.S. suppliers to “sell their products at a loss in the Indian market for up to eighteen months.”

AdvaMed, a trade association of medical device manufacturers, petitioned for the United States to review India’s eligibility for the GSP program and testified at the public hearing on the matter, like the dairy groups.

Digital Economy

With the rise of the digital economy, and with India’s growing heft as a hub for information technology services and for digital businesses, new frictions have emerged over data localization, data privacy, and e-commerce. Unlike China, which largely operates on its own digital systems, India uses many U.S. platforms, and many U.S. companies have back-office operations in India. These platforms, enjoyed by India’s half a billion internet users, generate enormous data flows, and Indian leaders are well aware of the tremendous value of this data. Prime Minister Modi has called it the “new oil” and “new gold.”

But the United States is concerned about how India has handled this new resource. In 2018, India’s central bank ordered companies “that operate a payment system in India”—meaning credit card companies and digital payment platforms such as PayPal—to store all data on local servers. This at first led to confusion about jurisdiction for cross-border transactions, and then a clarification that such data could be processed abroad but must ultimately be stored in India.

A vendor weighs vegetables next to an ad for Paytm, a digital payments firm, at a roadside market in Mumbai. Francis Mascarenhas/Reuters

In the e-commerce sector, long-standing rules prohibit foreign investment in platforms that sell directly to consumers, so foreign e-commerce operators in India use a marketplace model. That means they provide the technology platform to connect buyers with sellers. A midstream change in December 2018 to e-commerce rules about subsidiaries of foreign-owned platforms earned mention in the 2019 U.S. National Trade Estimate about limiting access to India’s market.

Finally, India is developing a comprehensive data protection policy. Digital economy experts say a new bill introduced in Parliament in December 2019 is similar to the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation. The current draft offers provisions for individual data protections, provides carve-outs for specific government requests for data, and creates a new identity verification proposal for social media. Much could change as legislators review and debate the bill, but given the size of India’s digital economy, these issues will only become more central to U.S.-India trade relations.

Visas in Services Trade

Most of the above flash points center on U.S. concerns about the Indian economy, mostly because the U.S. economy presents fewer barriers. Yet, the Indian government has continued to highlight services trade and the “movement of natural persons,” or procedures typically involving a visa regime by which a citizen of one country can perform services work in another country. For India, this falls squarely in the world of trade, but for the United States, these are immigration matters that cannot be negotiated in trade deliberations. In the United States, H1B and L1 visas permit highly skilled workers from other countries to be employed, with an annual limit of sixty-five thousand regular applications and another twenty thousand for those who have earned an advanced degree in the United States.

Due to its large pool of highly skilled workers, India is extremely competitive in services, and its professionals work around the world. Of the top ten companies [PDF] with H1B-approved petitions in 2018, four are Indian firms, three of which are at the very top. Over the past fifteen years, the proportion of approved H1B petitions from India went from just under 40 percent to more than 70 percent. India’s negotiating posture has long prioritized further opening other countries’ visa regimes for services workers; this was an unmet ambition, for example, of India’s in talks on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, a trade pact of fifteen countries, including China, that India opted out of after years of negotiations.

The Indian government continues to object to U.S. laws passed in 2010 and 2015 that apply higher fees on companies with more than fifty employees if more than half of those employees are in the United States as nonimmigrants. In 2016, India filed a trade dispute at the WTO over these visa fees, arguing that the higher fees “raised the overall barriers for service suppliers from India.” The WTO dispute is ongoing. India has also expressed concerns over visa processing delays, including more requests for evidence, which prolong review times, and increased rejection rates under the Trump administration.

No comments:

Post a Comment