By Ankit Panda

Researchers at the Center for Strategic and International Studies recently published a survey of Southeast Asian “strategic elites” (PDF) on their views on a range of geopolitical questions pertaining to the future of the Indo-Pacific. The exercise is a helpful source of insight into how Southeast Asia, long seen as one of Asia’s most economically dynamic and geopolitically significant sub-regions, sees competition between the United States and China, among other questions.

Researchers at the Center for Strategic and International Studies recently published a survey of Southeast Asian “strategic elites” (PDF) on their views on a range of geopolitical questions pertaining to the future of the Indo-Pacific. The exercise is a helpful source of insight into how Southeast Asia, long seen as one of Asia’s most economically dynamic and geopolitically significant sub-regions, sees competition between the United States and China, among other questions.

The CSIS results make for interesting side-by-side reading with previous efforts in this area — most notably the most recent survey report published by the Singapore-based ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute (PDF) surveying Southeast Asian elites on similar issues.

The CSIS report’s findings are largely in line with what the ISEAS survey found: China is gaining ground in the region and the United States is losing it. The CSIS team, as its top finding, notes that “China is seen as holding slightly more political power and influence than the United States in Southeast Asia today and considerably more power relative to the United States in 10 years.”

Separately, in economic terms, “the region views China as much more influential than the United States today, and this gap is expected to grow in the next 10 years.” Analysts will likely spend much time debating how much of this shift was inevitable and and how much of it — and to what degree — was accelerated by the policies and diplomatic style of the Trump administration.

It’s clear from the CSIS effort — and from speaking to many of these same strategic elites in the region — that the defining geopolitical question for each and every Southeast Asian capital is how competition between the United States and China may shake out. Interestingly, with the exception of elites in Vietnam and the Philippines, who cited the possibility of conflict in the South China Sea as their top concern, all others worried about the direct and indirect effects of U.S.-China strategic competition.

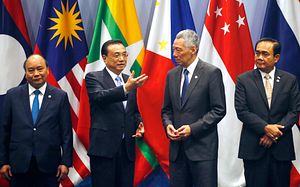

In this latter category, perhaps the view expressed recently by Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong in Foreign Affairs most aptly captures how many Southeast Asian states will look to cope. With the exception of Cambodia and Laos, which are much closer to China than the United States, the rest of Southeast Asia has insisted that it’s content to sit on the fence as competition plays out.

As Lee writes, “Asian countries do not want to be forced to choose between the two”—a common refrain in the region. While his essay makes a considerable case for a return by the United States to its pre-Trump role as the guarantor of Asia’s regional status quo rather than a revisionist in its own right (on trade, especially), Lee does not similarly outline a clear vision for what China might do.

Another finding here from surveys is that there remains considerable disagreement within Southeast Asia on the right mode of engagement with Beijing. As the CSIS researchers observe, a regional “consensus” on whether China is benign or revisionist does not yet exist; a “slight majority” of respondents to the CSIS survey expressed a benign view of China, by contrast.

All of this presents a challenging environment for the United States as it seeks to persuade regional states that China is deeply revisionist and that it is the United States that will uphold a “free and open” Indo-Pacific region.

Perhaps one bright area for Washington emerging from this and other surveys is that swing-powers with an affinity for the U.S. vision of Asia—including countries like Japan, India, and South Korea—are viewed positively in Southeast Asia as well. If the United States might succeed in its strategic goals in this region, it likely won’t do so alone.

No comments:

Post a Comment