For more than two millennia, Chinese leaders saw their country as one of the dominant actors in the world. The concept of zhongguo—the Middle Kingdom, as China calls itself—is not simply geographic. It implies that China is the cultural, political, and economic center of the world. This Sino-centrist worldview has in many ways shaped China’s outlook on global governance—the rules, norms, and institutions that regulate international cooperation. The decline and collapse of imperial China in the 1800s and early 1900s, however, diminished Chinese influence on the global stage for more than a century.

In the past two decades, China has reemerged as a major power, with the world’s second largest economy and a world-class military. It increasingly asserts itself, seeking to regain its centrality in the international system and over global governance institutions.

These institutions, created mostly by Western powers after World War II, include the World Bank, which provides loans and grants to developing states; the International Monetary Fund, which works to secure the stability of the global monetary system; and the United Nations, among others. President Xi Jinping, the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao Zedong, has called for China to “lead the reform of the global governance system,” transforming institutions and norms in ways that will reflect Beijing’s values and priorities.

Journalists watch an image of Chinese President Xi Jinping speaking at the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing in April 2019. Greg Baker/AFP/Getty Images

Crew members of a Chinese container ship wave Chinese and Panamanian flags during an official visit by Chinese President Xi Jinping to the country in December 2018.

Luis Acosta/AFP/Getty Images

Crew members of a Chinese container ship wave Chinese and Panamanian flags during an official visit by Chinese President Xi Jinping to the country in December 2018. Luis Acosta/AFP/Getty Images

China is pursuing a multipronged strategy toward global governance. It supports international institutions and agreements aligned with its goals and norms, such as the World Bank and the Paris Agreement on climate change. Yet, on issues in which Beijing diverges from the norms of the current system, such as human rights, it seeks to undermine those values and create alternative institutions and models. In areas where norms and institutions are still being established, such as internet governance, China works with other authoritarian powers such as Russia to create standards that reflect their interests.

China has become a powerful force in global governance. Increasingly, its efforts appear to be deepening divides with other countries, particularly democracies that are committed to existing norms and institutions. Ultimately, this divide could make it harder for states to collaboratively address major international challenges. The divide could even create two distinct systems of global governance, badly undermining multilateral cooperation.

Imperial China

(Third Century BCE to 1900s)

For over two thousand years, beginning with the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE) and ending with the collapse of the Qing (1644–1911 CE), imperial Chinese leaders perceived themselves as rulers of the world, even though Beijing had never built a global empire. Even when China’s influence collapsed in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Chinese leaders dreamed of regaining global influence.

Han dynasty, extent at around 100 BCE

Imperial China’s Views on International Order

Imperial Chinese leaders did not think of global governance as it is defined today but maintained views on regional order. Chinese emperors made territories and kingdoms in the imperial orbit dispatch envoys to perform ritualistic submissions. This regional order was a predecessor of global governance.

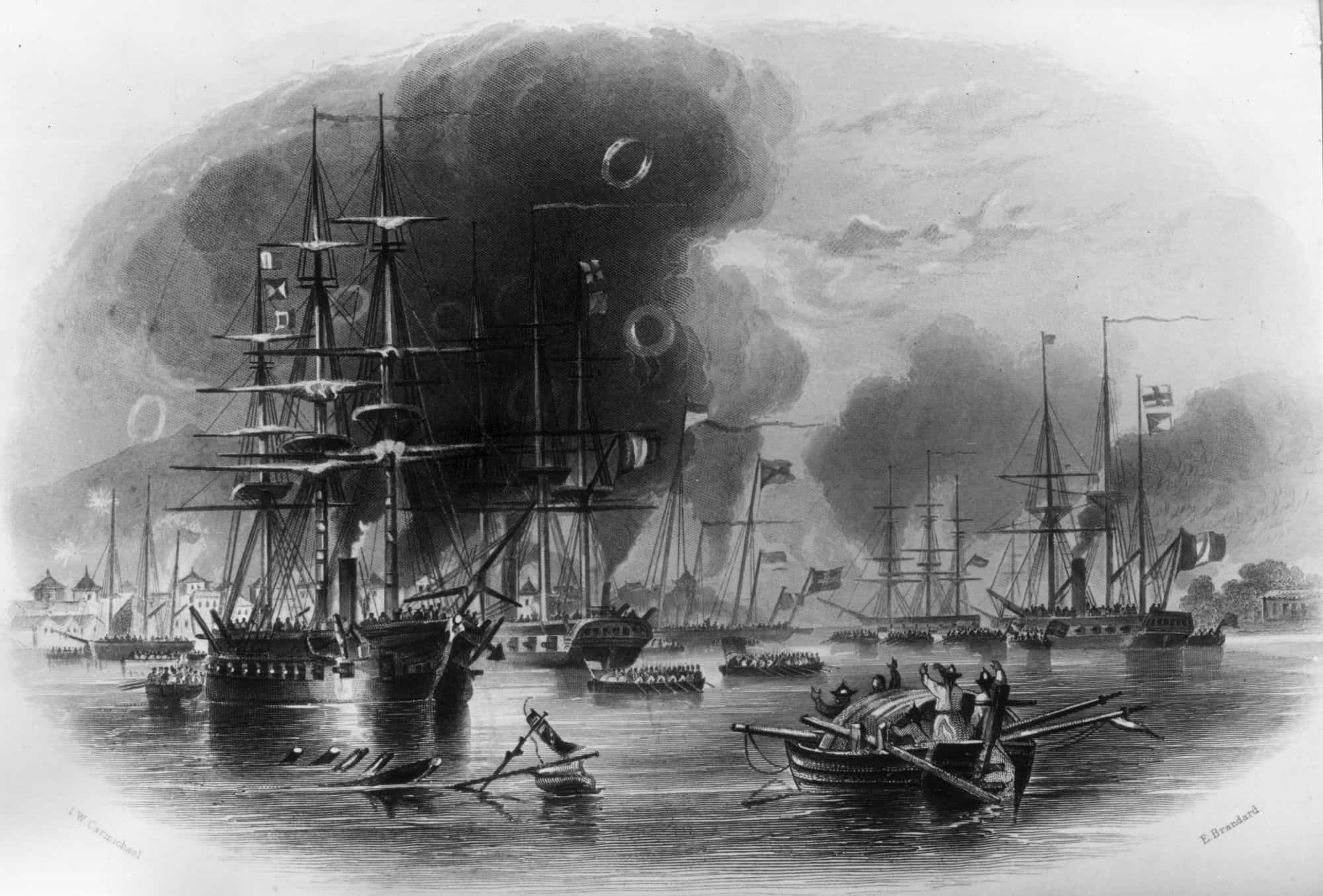

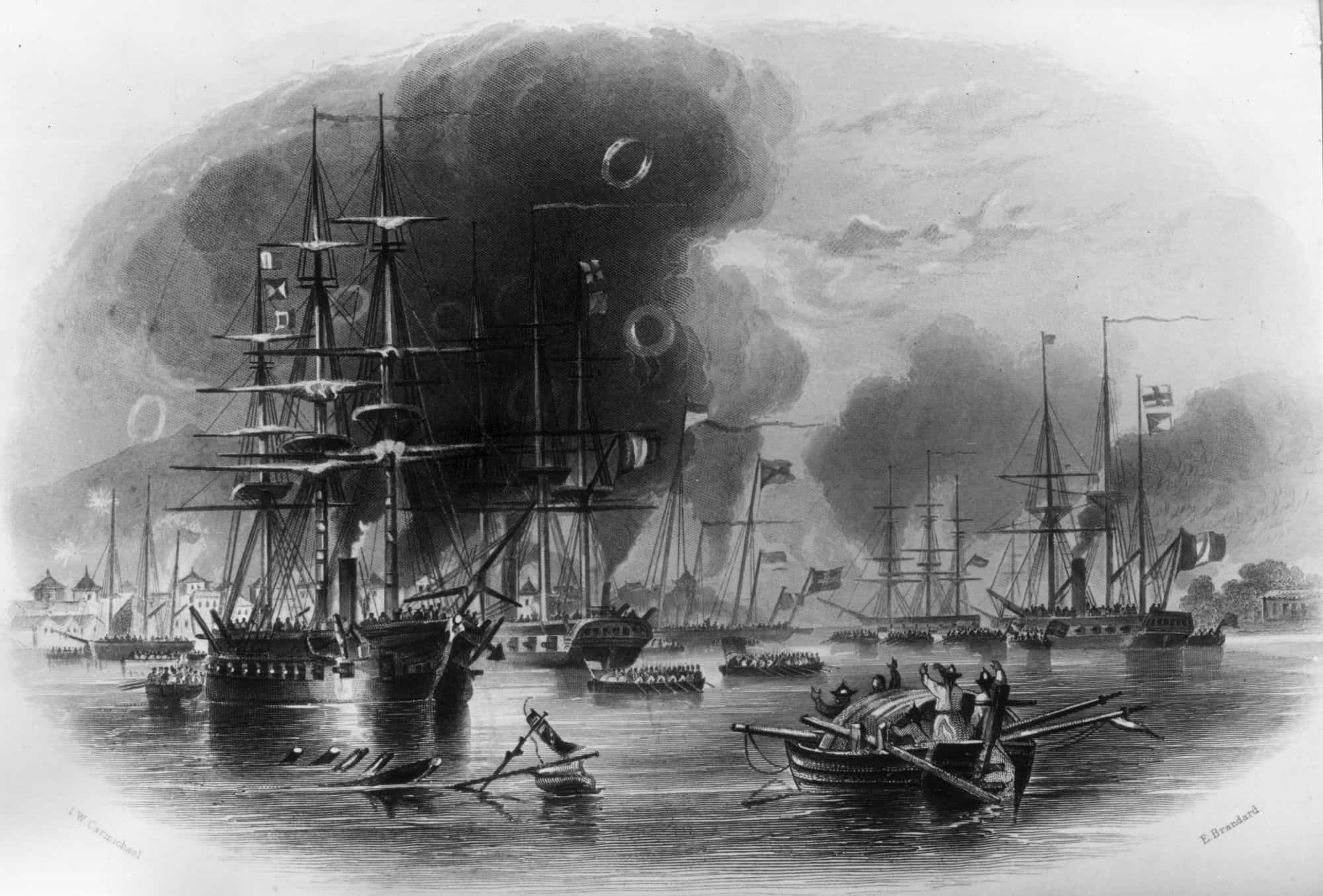

The bombardment of Canton (Guangzhou) during the first Opium War, in 1839.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The bombardment of Canton (Guangzhou) during the first Opium War, in 1839. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The Collapse of Imperial China

Until the 1840s, China remained a major power. But China’s regional dominance was destroyed in the late 1800s and early 1900s as Britain defeated it in the Opium Wars and as other major powers carved out territories in the country. The last dynasty collapsed in 1911.

Sun Yat-sen, pictured here at the Ming Tombs, was the father of modern China and pushed for reforms in the post-imperial period.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Sun Yat-sen, pictured here at the Ming Tombs, was the father of modern China and pushed for reforms in the post-imperial period. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Aspirations to Power

Despite defeat, China’s leaders maintained the idea that one day the country would again be the center of the world. Sun Yat-sen, known as the father of modern China, was one of the first to advocate for “revitalizing the Chinese nation”. But the Republic of China (founded in 1912) was a weak state, unable to play a role in global governance. A long civil war in the 1930s and 1940s between Communist and Nationalist forces weakened China further.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

STAGE 2

Revolutionary China

(1949–1976)

At the end of World War II, China became an initial member of the United Nations and seemed poised to play a larger role in the new international order. But after the Communist Party won the civil war and took power in 1949, China rejected the international system and tried to help create an alternative global governance order.

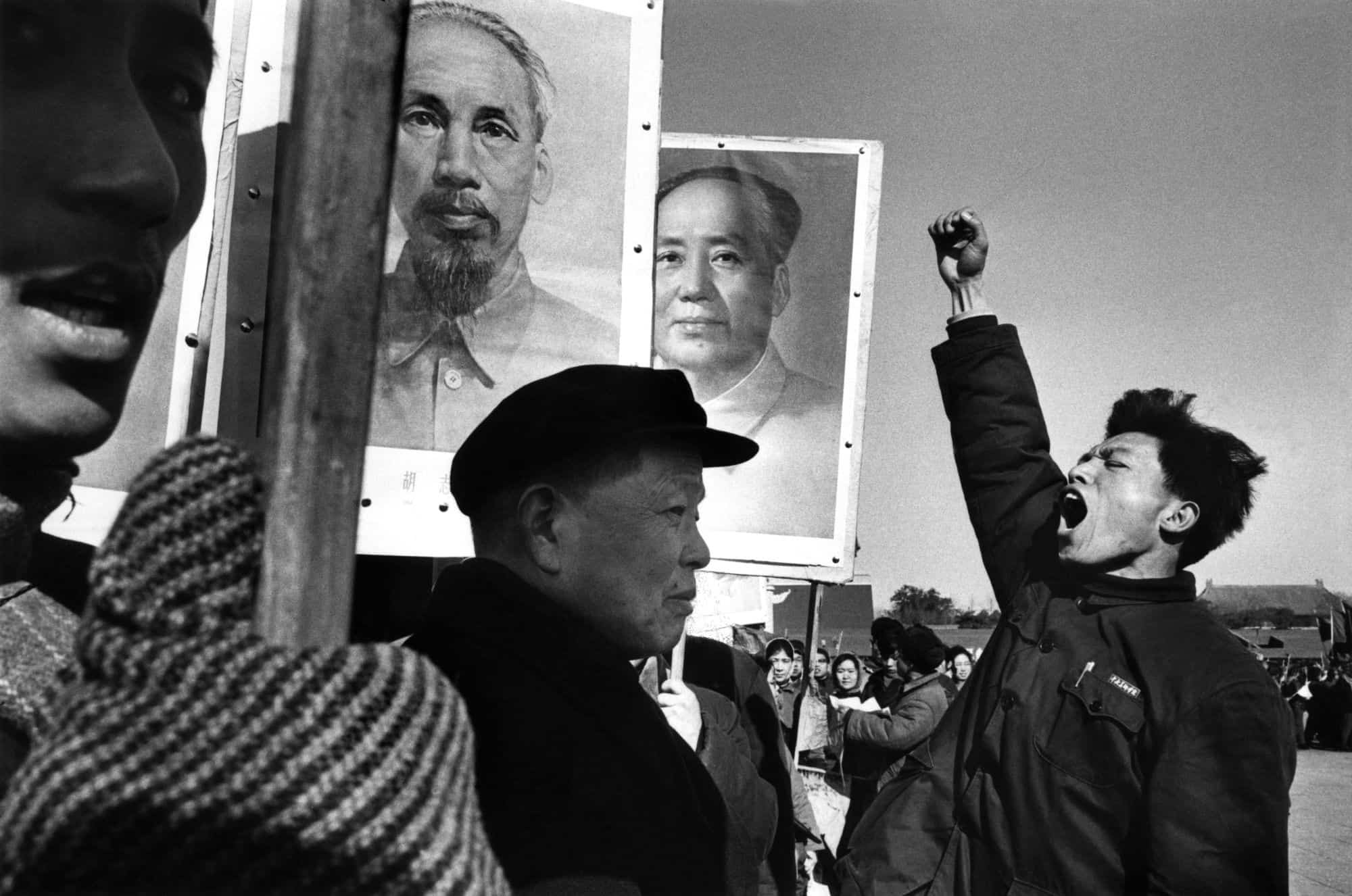

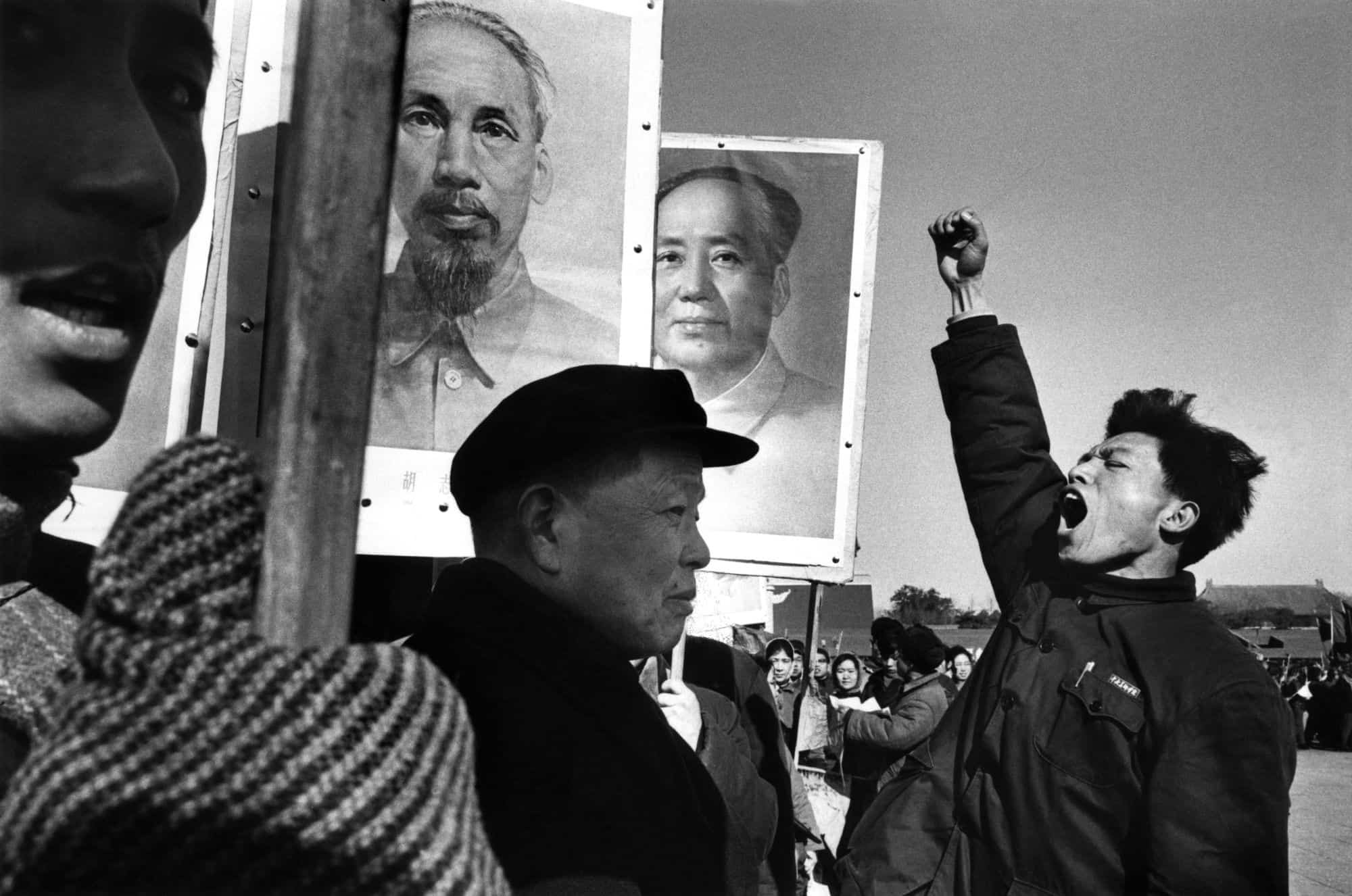

Demonstrators in China protest against U.S. intervention in Vietnam, a close Chinese partner, in 1965.

Marc Riboud/Fonds Marc Riboud au MNAAG/Magnum Photos

Demonstrators in China protest against U.S. intervention in Vietnam, a close Chinese partner, in 1965. Marc Riboud/Fonds Marc Riboud au MNAAG/Magnum Photos

Mao Challenges Global Institutions

Frustrated with the existing international system—the Republic of China (Taiwan) remained seated on the UN Security Council, instead of the People’s Republic of China—Beijing promoted alternative values and institutions. In 1953, Premier Zhou Enlai enunciated “The Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence”—mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual nonaggression, noninterference in each other’s internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence. Endorsed by leaders of many newly independent former colonies, these principles formed a basis for the nonaligned movement (NAM) of the 1960s. NAM became a counterweight to Western-dominated global governance.

Under Mao Zedong, Beijing trained guerrilla fighters in many parts of the world, such as these guerrillas in the Democratic Republic of Congo, in May 1968.

Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone/Getty Images

Under Mao Zedong, Beijing trained guerrilla fighters in many parts of the world, such as these guerrillas in the Democratic Republic of Congo, in May 1968. Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone/Getty Images

China Supports a More Radical Approach

By the 1960s, Beijing tried more directly to subvert the existing international order, often by exporting revolution. China trained and armed antigovernment guerrilla forces in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia.

UN Ambassadors converse as the United Nations prepares to welcome China back into the body, in October 1971.

Bettmann/Getty Images

UN Ambassadors converse as the United Nations prepares to welcome China back into the body, in October 1971. Bettmann/Getty Images

China Returns to the International System

China returned to the international system in the early 1970s and rebuilt its ties with the United States. In the 1970s, it accepted a weaker international role and sought to participate in the institutions and rules set up after World War II. In October 1971, the UN General Assembly voted to admit the People’s Republic of China as a member and as one of the five permanent members of the Security Council.

David Hume Kennerly/ Getty Images

STAGE 3

Reforming China

(1977–2000)

After the end of the Mao era, China opened up in the 1980s and 1990s, reformed its economy, and increased its role in global governance, including by cooperating with international institutions. During this time, China adapted many domestic laws to conform to those of other countries.

Deng Xiaoping, Nancy Reagan, and Ronald Reagan stand together at the Great Hall of the People as China builds closer ties to the rest of the world, in April 1984.

Bettmann/Getty Images

Deng Xiaoping, Nancy Reagan, and Ronald Reagan stand together at the Great Hall of the People as China builds closer ties to the rest of the world, in April 1984. Bettmann/Getty Images

After Mao’s Death, China Rejoins the World

No comments:

Post a Comment