By Yanzhong Huang and Joshua Kurlantzick

For more than two millennia, Chinese leaders saw their country as one of the dominant actors in the world. This Sino-centrist worldview has in many ways shaped China’s outlook on global governance — the rules, norms, and institutions that regulate international cooperation. The decline and collapse of imperial China in the 1800s and early 1900s, however, diminished Chinese influence on the global stage for more than a century.

For more than two millennia, Chinese leaders saw their country as one of the dominant actors in the world. This Sino-centrist worldview has in many ways shaped China’s outlook on global governance — the rules, norms, and institutions that regulate international cooperation. The decline and collapse of imperial China in the 1800s and early 1900s, however, diminished Chinese influence on the global stage for more than a century.

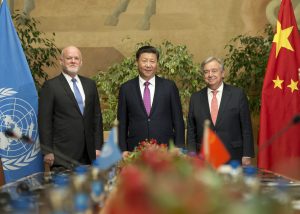

But in the past two decades, China has reemerged as a major power, with the world’s second largest economy and a world-class military. It increasingly asserts itself, seeking to regain its centrality in the international system and over global governance institutions. President Xi Jinping, the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao Zedong, has called for China to “lead the reform of the global governance system,” transforming institutions and norms to reflect Beijing’s values and priorities.

China is pursuing a multipronged strategy toward global governance. It supports international institutions and agreements aligned with its goals and norms, such as the World Bank and the Paris Agreement on climate change. Yet, on issues in which Beijing diverges from the norms of the current system, such as human rights, it seeks to undermine those values and create alternative institutions and models. In areas where norms and institutions are still being established, such as internet governance, China works with other authoritarian powers to create standards that reflect their interests.

China has become a powerful force in global governance. Increasingly, its efforts appear to be deepening divides with other countries, particularly democracies that are committed to existing norms and institutions. Ultimately, this divide could make it harder for states to collaboratively address major international challenges, such as global health and development finance.

For over 2,000 years, beginning with the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE) and ending with the collapse of the Qing (1644–1911 CE), Chinese emperors perceived themselves as rulers of the world, even though Beijing had never built a global empire. Even when China’s influence collapsed in the 19th and 20th centuries, Chinese leaders dreamed of regaining global influence.

At the end of World War II, China became an initial member of the United Nations and seemed poised to play a larger role in the new international order. But after the Communist Party won the civil war and took power in 1949, China rejected the international system and tried to help create an alternative global governance order, through the Non-Aligned Movement, and by fomenting revolution in some Asian and African countries.

China returned to the international system in the early 1970s and 1980s and rebuilt its ties with the United States. It accepted a weaker international role and sought to participate in the institutions and rules set up after World War II. Then, after the Tiananmen crackdown, and China’s subsequent isolation in international affairs, to help rebuild its reputation and ties with other countries, beginning in the early 1990s Beijing increasingly embraced multilateralism and integration with global governance institutions. It acceded to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty in 1992, signed the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in 1996, and signed the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in 1998. Even into the first decade of the 21st century, China often proved willing to play by international rules and norms.

As its economy grew, however, Beijing assumed a more active role in global governance, signaling its potential to lead and to challenge existing institutions and norms. The country boosted its power in four ways: it took on a bigger role in international institutions, advertised its increasing influence, laid the groundwork to create some of its own organizations, and sometimes subverted global governance rules. China started to create Beijing-dominated institutions, a process that would expand in the 2010s.

Now, since the early 2010s, as China’s economic and military power has grown, so too have its ambition and capability to reform the global governance system to reflect Beijing’s priorities and values. Some priorities Beijing promotes are defensive in nature, and reflect long-standing Chinese aims: preventing criticism of China’s human rights practices, keeping Taiwan from assuming an independent role in international institutions, and protecting Beijing from compromises to its sovereignty. Yet China also now seeks to shape the global governance system more offensively, to advance its model of development.

Under Xi, China has become much more assertive on global governance issues. Xi has declared that China needs to “lead the reform of the global governance system with the concepts of fairness and justice.” The terms “fairness and justice” signal a call for a more multipolar world, one potentially with a smaller U.S. role in setting international rules. China has gained clout in international organizations traditionally dominated by Western countries. Today, former Chinese officials lead four of the 15 UN specialized agencies.

Beijing also is building its own, China-centered institutions. In 2013, Beijing launched the Belt and Road Initiative, a vast plan to use Chinese assistance to fund infrastructure in, and boost ties with, other countries.

In some areas, China’s assertiveness may have positive implications for the world. In the past decade, China has shifted from resisting international cooperation on climate change to supporting such cooperation. For years, Beijing had been skeptical about multilateral approaches to climate change, worrying they could slow China’s growth. Yet at home, China has reduced the role of fossil fuels in its energy mix and become the world’s biggest investor in renewable energy. China’s activism at home has been matched by new activism on the global stage. In 2015, the United States partnered with China to call for a strong, legally binding treaty that ultimately became the Paris Agreement. Now Beijing is trying to help save the agreement after the Trump administration announced the U.S. would withdraw.

But in other areas, Beijing’s approach could divide the international community, with serious repercussions. China seeks to become a leader in global internet governance and to promote the idea of “cyber sovereignty” — that a state should exert control over the internet within its borders. Globally, Beijing promotes its domestic cyber sovereignty approach to internet governance, which hinges on Communist Party control and censorship. China’s domestic internet offers an alternative to existing, freer models of internet governance, and Beijing also uses its influence at the United Nations and other forums to push countries to adopt more closed internets. Meanwhile, Chinese corporations such as Huawei and CloudWalk have supplied repressive governments in Venezuela and Zimbabwe with surveillance tools like facial recognition technology.

In other areas, the end result remains less clear. China has pursued both unilateral and multilateral approaches to development finance. In one case, with the BRI Beijing operates according to its own standards; in the other, with the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, it has adopted international aid standards.

Still, China’s increasingly assertive presence could prove divisive, especially in areas like internet governance, where Beijing’s approach could marginalize existing institutions and spark serious divides. If China (and Russia) can set the standards for internet governance, for instance, they could pave the way for other countries to embrace cyber sovereignty, sparking a divided world with two internets — one generally open and the other closed and favored by autocracies.

This article is adapted from the new Council on Foreign Relations Infoguide, “China’s Approach to Global Governance.”

Yanzhong Huang is Senior Fellow for Global Health at the Council on Foreign Relations

Joshua Kurlantzick is Senior Fellow for Southeast Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations

No comments:

Post a Comment