MURAT AKAN

With due respect and compassion to all who are fighting or have survived COVID-19, for the majority of us, this experience has been one of day-to-day confinement. The monotony broken, perhaps, by a collective moment of clapping for health care workers. I recall Achilles’ critique of hero culture, “Stay at home or fight your hardest – your share will be the same. Coward and hero are honoured alike. Death does not distinguish do-nothing and do-all” (Iliad 9:316-358). Here we are, in the 21st century, still partaking in hero culture. If anything, the doctors and nurses, whose efforts world leaders described as selfless, are the true victims of our state of statelessness as they were left unprepared in all respects of medical capacity.

With due respect and compassion to all who are fighting or have survived COVID-19, for the majority of us, this experience has been one of day-to-day confinement. The monotony broken, perhaps, by a collective moment of clapping for health care workers. I recall Achilles’ critique of hero culture, “Stay at home or fight your hardest – your share will be the same. Coward and hero are honoured alike. Death does not distinguish do-nothing and do-all” (Iliad 9:316-358). Here we are, in the 21st century, still partaking in hero culture. If anything, the doctors and nurses, whose efforts world leaders described as selfless, are the true victims of our state of statelessness as they were left unprepared in all respects of medical capacity.

With due respect and compassion to all who are fighting or have survived COVID-19, for the majority of us, this experience has been one of day-to-day confinement. The monotony broken, perhaps, by a collective moment of clapping for health care workers. I recall Achilles’ critique of hero culture, “Stay at home or fight your hardest – your share will be the same. Coward and hero are honoured alike. Death does not distinguish do-nothing and do-all” (Iliad 9:316-358). Here we are, in the 21st century, still partaking in hero culture. If anything, the doctors and nurses, whose efforts world leaders described as selfless, are the true victims of our state of statelessness as they were left unprepared in all respects of medical capacity.

With due respect and compassion to all who are fighting or have survived COVID-19, for the majority of us, this experience has been one of day-to-day confinement. The monotony broken, perhaps, by a collective moment of clapping for health care workers. I recall Achilles’ critique of hero culture, “Stay at home or fight your hardest – your share will be the same. Coward and hero are honoured alike. Death does not distinguish do-nothing and do-all” (Iliad 9:316-358). Here we are, in the 21st century, still partaking in hero culture. If anything, the doctors and nurses, whose efforts world leaders described as selfless, are the true victims of our state of statelessness as they were left unprepared in all respects of medical capacity.

This is not the first time the world has faced a pandemic. We can consider earthquakes in the same way: It is not the earthquake or the pandemic but poor construction and poor healthcare systems that kill. Years of neoliberal policies have fragilized our states and economies. The world has no infrastructural buffer; it has been continuously on the verge of bursting into tears or violence as Alejandro González Iñárritu’s film Babel vividly portrayed, it just was uncertain as to which direction to take. Usually religious organizations and right-wing politics run on donations, now the entire world hangs together by the threads of donation culture.

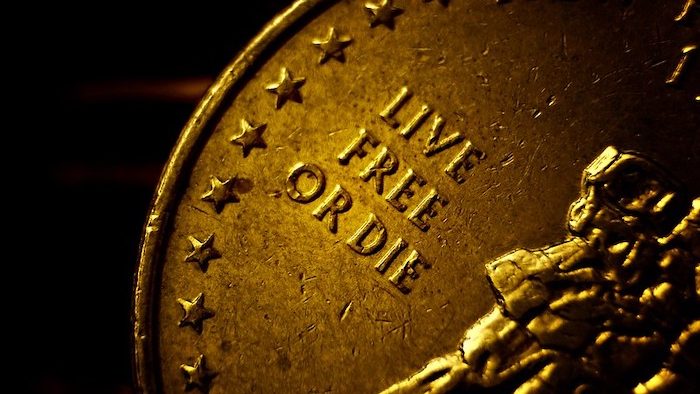

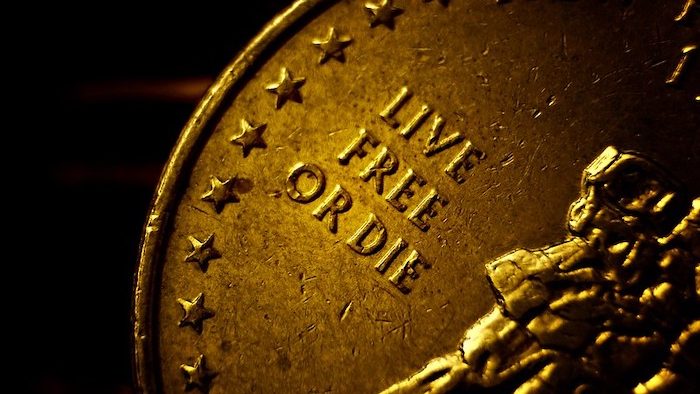

Behind the slogans materializing most concretely in the United States, “live free or die,” “economy or lives” were multiple layers of ignorance. The economy was already dead before COVID-19. We used to be able to buy a good lunch for less than three dollars in 1996 in New York; I could not buy that same lunch for 10 dollars when I was in New York in 2018 for the memorial celebration of my dissertation advisor Alfred Stepan. Through time spent at Yale, Columbia, Oxford, and Central European University, he dedicated his career to democratization. In one of his last articles with Juan Linz he argued that the idea of American exceptionalism just served to cover its poor quality of democracy. Combine the slogan “live free or die,” – proof of no sense of public life and responsibility whatsoever – with Charles Ferguson’s award winning documentary on the 2008 economic crisis, the Inside Job, and you will seriously consider the hypothesis that the USA is an oligarchy with fascistic tendencies. Trump is just the tip of the iceberg.

It is perhaps no wonder that one of Netflix’s most popular offerings is La Casa de Papel (Money Heist), a bank robbery that questions our moral and economic order and the telos of human existence. La Casa de Papel recovers a sense of justice, sets scores right at least in our imaginations in this topsy turvy world in whose institutions we had lost faith long before the virus.

What unravelled with the advent of the virus was the realisation that this fragile world could not even have a crisis. A world crisis presupposes that the world shares equally a crisis experience. This was hardly the case. On the one hand, the threat of a virus equalized the poor and the rich; neither Tom Hanks’ riches nor Boris Johnson’s status could help in insulating them from contracting the virus. On the other hand, the World could not equally confine; millions of Indian migrant labourers had to walk hundreds of miles home, French Carrefour cashiers and American Meat Plant workers lost their lives. As one graffiti in Nantes, France put it; “At work, we are 150 in the same room, at home, we don’t have a right to invite our neighbour.” Those whose work category was deemed “essential” could not equally confine, some lost their jobs, some confined in gardened villas and others were packed into a few square meters, yet others were victims of domestic violence.

Inequality of experience continues in politics. While some countries witnessed a republican moment, the differences between left and right politics levelled out, and public accountability and responsibility ranked high; in others politics intruded into the crisis. While the French president was reporting to the public in all humbleness in India, Modi turned COVID-19 into a “Muslim virus,” Trump into a “Chinese virus.” Orbán’s Enabling Act in Hungary now allows the executive to rule by decrees for an indefinite period of time. Erdoğan perfected his control over opposition and society. Turkey’s motto for fighting the virus is Biz bize yeteriz” [We are sufficient for ourselves] written on a Turkish flag. Soaked in nationalism, even in a world crisis, Turkey could not pronounce a word of universalism and internationalism.

While watching this World who has lost touch with its humanity, or perhaps it is more accurate to say ‘its animality,’ to a degree that it could not even live a crisis, two verses kept turning in my head. One from T. S. Eliot’s Little Gidding,

We shall not cease from exploration

the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

And, the other from Nazım Hikmet’s On Living:

you must take living so seriously

that even at seventy, for example, you’ll plant olive trees—

and not for your children, either,

but because although you fear death you don’t believe it,

because living, I mean, weighs heavier.

Both passages remind me that the we need reconnect with our humanity and environment on our own terms and stop waiting for heroes. I hope the pause of business-as-usual across our socieites made it clear how meaningless it was before and still is. When leaders declared the majority of our economic activities as “non-essential,” they were talking and acting out of exigencies of the pandemic. But, at the same time, they were giving away a hard truth – most of our activities in the ways they are defined, measured, categorized and prioritized are in fact “non-essential” exigencies of the division of labour imposed by the capitalist world order. A human being can only realize this essence under confinement, because when there is no pandemic, there is capitalism to confine us to ensure that we have no time to discover our essence, but only to live it as dictated. Even the ones among us whom we would consider the freest because they leave in the free parts of the world are dominated.

No comments:

Post a Comment