Recalling the experience of working on the grand strategy volumes of the British Government’s official history of the Second World War, Sir Michael Howard remarked that “the editor never told me what Grand Strategy was, and none of my colleagues seem to have asked.” Finding no definition of the term, Howard was obliged to make up his own.[1] This conceptual uncertainty has been a feature of debates over grand strategy ever since. A recent exchange on Twitter encapsulated the problem. In it, the philosopher and military ethicist Professor Pauline Shanks Kaurin asked for a definition of the term. When asked why she had posed the question, she made the honest admission that, “I sat in on a lecture on [Grand Strategy] and geopolitics today and I realized I’m not sure I understand what [Grand Strategy] is precisely.” Just as Howard had encountered half a century earlier, the resulting replies made clear that reliable definitions of grand strategy are hard to come by.

This lack of a clear or usable definition has prompted a series of attempts to try and provide clarity to discussions of grand strategy.[2]

Many of these, including those by Paul Kennedy, Hal Brands, and Lukas Milveski, make an attempt to understand grand strategy by returning to history.[3] By discovering the term’s origins, it is argued, they can pinpoint fundamental aspects of its meaning and evolution. Their efforts tend to locate the inception of grand strategy to the late-nineteenth or early twentieth centuries, and to associate it with familiar figures from the canon of strategic studies. Alfred Thayer Mahan, Julian Corbett, J.F.C. Fuller, Basil Liddell Hart, and Edward Mead Earle have all been cast as key contributors to the debate at one time or another.

Alfred Thayer Mahan, Julian Corbett, J.F.C. Fuller, B.H. Liddell Hart, and Edward Meade Earle (Wikimedia, Britannica, and the Institute for Advanced Study)

These writers are credited with apprehending that the word strategy could meaningfully be applied beyond the conduct of military activity, and even beyond war itself. Their expansion of the term to encompass issues of economics, psychology, and morale is thus cast as an inevitable and appropriate reaction to the changing character of twentieth-century warfare. As Earle argued in 1943, “As war and society have become more complicated—and war, it must be remembered, is an inherent part of society—strategy has of necessity required increasing consideration of non-military factors.”[4] This narrative of strategic progress is visible in a number of more recent works on the topic. As Hal Brands argues, “The concept grew out of the shortcomings of the traditional definition of ‘strategy,’ which was often construed rather narrowly, as the coordination of purely military blows to defeat an enemy.” For him, this was an elemental error of perspective, since “across the expanse of human history, winning wars has required more than simply winning battles.”[5] Yet contained within this interpretation are crucial conceptual tensions, which an appreciation of history can help us to reveal.

Most accounts stress that grand strategy has been a fundamental feature of all statecraft across time. Historians as influential as Paul Kennedy and John Lewis Gaddis argue that “all states have a grand strategy, whether they know it or not.”[6] If this is so, then why did it take until the Second World War for a term to emerge describing such a crucial quality? If grand strategy has been an historically continuous element of statecraft, then understandings of strategy must surely have encompassed more than the mere fighting of battles before 1945? Moreover, the idea that mankind has progressed towards a more effective understanding of strategy across time—moving towards the inclusive modern application of the term—risks straying into a Whiggish account by which we assume an increasing capacity to influence events that are often far beyond the control of statesmen and women.[7] As Patrick Porter has argued, an intellectual framework of this nature can be extremely problematic when applied to the security challenges of the present—underpinning over-inflated notions of agency in world affairs, and assisting in the rationale offered in justification of unrestrained interventionism.[8]

Some of the most notable proponents in debates over grand strategy have been distinguished historians—among them Kennedy and Gaddis. Yet at the same time, the discipline of history itself has been remarkably reluctant to engage in discussions of strategy. This has contributed to a situation whereby history is used to emphasize continuity in the practice of grand strategy—buttressing the idea that grand strategy is something that has always happened—rather than to challenge ideas and assumptions within broader debates on the topic. This is an unfortunate oversight, as history has a vital role in sharpening our analysis of strategy. As Hew Strachan has argued, viewing strategy as ubiquitous in the annals of statecraft conflates strategic theory with strategy in practice.[9] Doing so confuses our understanding of strategy in the modern world by depicting the inherently responsive, changing nature of strategic action by governments with the long-term continuities of strategic theory.

Returning to the origins of the idea of grand strategy makes this much clear. Doing so reveals that grand strategy was not an idea born of the experience of the First or Second World Wars. Nor was it a concept regarded as an inherent aspect of statecraft. Rather, an identifiably modern notion of grand strategy was the product of the British Empire’s anxieties over its global security challenges. Writing at the turn of the twentieth century, the Edwardian courtier Lord Esher argued:

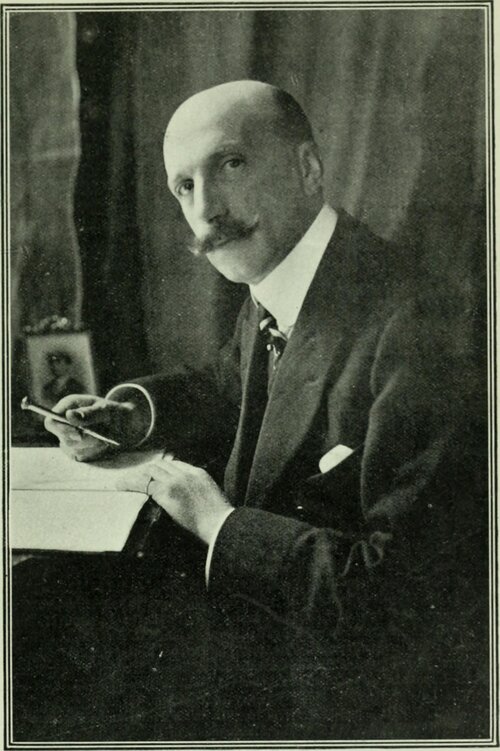

Lord Esher in 1905 (Wikimedia)

The questions confronting the Great General Staff of the German Army are constantly undergoing revision, but they are simple and stable compared with those affecting our world-wide Empire, and they are purely military. There is, on the other hand, hardly any point on the earth’s surface which can change ownership, and certainly not a modification in the relative power of two foreign states, can take place without affecting the National Strategy of Great Britain.[10]

Esher was making a crucial point: Britain ought to think differently about strategy owing to the unique geographical, political, and military circumstances of its worldwide Empire. This viewpoint was widespread within contemporary military thought.[11] As Rear-Admiral Herbert Richmond informed his students at the Royal Navy’s War College in 1920:

Clausewitz…must be read with caution by a maritime people…His experience was of continental war, not of sea war: and therefore, although his book is a monument of philosophico-military reasoning, it is by no means an infallible sea-military bible.[12]

For these writers, different states faced different strategic imperatives, which demanded alternative approaches and intellectual frameworks. This logic found its broadest form in Liddell Hart’s British Way in Warfare, and begs fundamental questions about the viability of grand strategy as a form of strategic theory.

This brief foray into history raises some wider points about what grand strategy is or is not, and what it may or may not mean. Above all, grand strategy is a concept rooted in the demands of making strategy in the real world. It was never intended to be a universal contribution to strategic theory, and ought not to be regarded as such. This distinction is significant, because there is a fundamental danger in labeling all statecraft across time and place as being associated with a single idea of grand strategy. This is particularly so when commonly used understandings of the term are rooted in the anxieties of twentieth-century British or American military and political elites, often concerned with combating the threat of relative decline or expanding their imperial power. Anglo-American ideas of grand strategy are not a neutral category of analysis. To apply them blindly risks perpetuating past assumptions which were borne of different circumstances—many of which contained deeply hierarchical assumptions about national or racial superiority. It also obscures significant shifts within national traditions of strategic thought: as David Edgerton has illustrated, British grand strategy has varied widely over the twentieth century owing to fundamental shifts in the role of the state within British life.[13]

Above all, grand strategy is a concept rooted in the demands of making strategy in the real world. It was never intended to be a universal contribution to strategic theory, and ought not to be regarded as such.

The idea of grand strategy is equally problematic as a tool of international comparison, containing as it does a series of assumptions about the role of power in world affairs. Interpreting the actions of states from outside of the Atlanticist tradition through the prism of grand strategy can thus result in deeply misleading conclusions. As Dennis Showalter argued, “It is generally conceded that the German military could motivate soldiers, win battles, and orchestrate campaigns…But at the plane of grand strategy…the Germans appear as children.” Yet, as he rightly points out, “German military policies were not a denial of the concept of grand strategy, but rather its fulfillment—on German terms, to meet German needs.”[14] Much the same logic applies to interpreting the actions of states in the Global South, or in East Asia, today.

Does all of this mean grand strategy ought to be declared dead? I would argue not. But we do need to accept that grand strategy has no definitive or stable meaning, and that the term does not describe activities which are defined by similarity of equivalence. Understandings of strategy were given coherence through their connection to the enduring nature of war. Grand strategy has no such anchor. Thus, the terminology of grand strategy is a relatively recent, Anglophone attempt to describe and explain the evolution of a much more long-term and varied set of activities, traditionally located in the realm of policy or statecraft. As such, to account for the myriad differences and changes that have characterised how polities have pursued security across time, we must move towards a more flexible approach. History has a vital role to play here, acting to contextualise ideas and to widen the variety of perspectives within the discussion. Just as the historiographical turn in international relations has challenged and nuanced the interpretation of key texts within that discipline, so can a greater interface between history and strategic studies improve our understanding of strategy.[15]

No comments:

Post a Comment