WASHINGTON, DC: In the Covid-19 pandemic, neither China nor the United States has offered a creditable performance, and this puts immense pressure on the multilateral system.

WASHINGTON, DC: In the Covid-19 pandemic, neither China nor the United States has offered a creditable performance, and this puts immense pressure on the multilateral system.

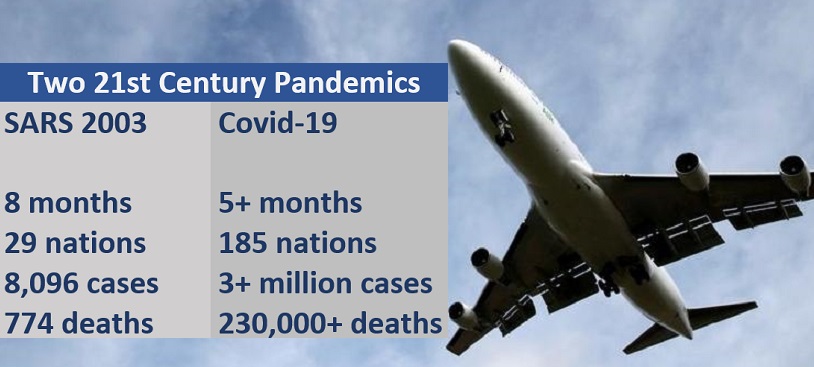

Most countries escaped SARS-CoV-1 in 2003. The virus hit 26 countries and only eight Americans tested positive for SARS, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The United States and many other nations were not prepared 15 years later when a new coronavirus emerged, much more threatening to lives and well-being. The SARS-CoV-1 virus infected just over 8,000 people worldwide and left 774 dead. By comparison, with SARS-CoV-2, nations report more than 3.1 million confirmed cases, with 225,000 deaths. As I wrote in 2003, such perils, rooted in globalization, cannot be defeated permanently.

Disruptors: Severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, was a preview for Covid-19, but many nations did not prepare (Source: US Centers for Disease Control and Johns Hopkins University)

Disruptors: Severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, was a preview for Covid-19, but many nations did not prepare (Source: US Centers for Disease Control and Johns Hopkins University)

Of course, pandemics are not the only threat confronting the world. But unlike armed conflicts where early warning is available, or climate change, which threatens lives in a slow motion, pandemics emerge unexpectedly. And that is a severe challenge for the global multilateral system, in place since World War II. That system was built around big multilaterals of the UN system, such as the International Monetary Fund; the World Bank; the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, later the World Trade Organization; along with specialized agencies like the World Health Organization, founded in 1948. Despite many agencies and tasks, the system was fundamentally geared for collective security, the foundational principle of the UN system, deterring and defeating aggression. The system must adapt to newer threats that can be far more deadly than war.

In recent years an array of emerging actors in a range of areas, including trade arrangements, climate change, humanitarian relief and health have contributed to growing fragmentation of global governance. But none compares with Donald Trump, whose disdain for multilateralism is visceral. Under Trump, the United States abandoned responsibility to lead common responses to common challenges, whether on its own or through alliances and institutions.

Before the virus hit, the Trump administration proposed cutting $3 billion in global health funding, including $123 million for the World Health Organization for fiscal year 2020. At an 8 April White House briefing, Trump warned that the United States would “put a very powerful hold” on WHO funding and criticized the Covid-19 response: “They missed the call…They seem to be very China-centric.”

By rejecting travel restrictions, initially accepting China’s early denial of human-to-human transmission, and not declaring Covid-19 a global pandemic until March 11 – after 118,000 cases of infection in more than 110 countries – the WHO leaves itself open to criticism and investigations. Early warnings and fact-finding missions are critical in pandemics.

China remains a much stronger supporter of the existing multilateral system, at least in theory. But China has also moved to create parallel mechanisms like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Belt and Road Initiative. The country, which has provided considerable bilateral aid to virus-stricken nations, first reported the coronavirus outbreak to WHO on 31 December. The WHO-China Joint Mission did not start until 16 February. It is fair to question whether an earlier mission might have provided timely information, prompting more action from the international community. According to a New York Times report, China held back on allowing a WHO mission, with sources blaming secretiveness, negligence, complacency and even a desire among Chinese scientists to produce the first publications on the new virus. WHO could have raised international attention, applying pressure for an earlier mission.

China also condemned Trump’s actions, such as ban on flights from China, as “excessive,” an example of how America “unceasingly manufactured and spread panic.” Yet the United States was not alone in banning flights, and Trump soon did the same for other nations. And the caution was warranted.

An angry Trump has suggested that if China was knowingly responsible, there “should be consequences.” The United States, the leading donor for WHO, is investigating whether the virus originated from a research laboratory in China, even though the organization suggests that no evidence suggests as much. Convincing proof is unlikely.

Still, any attempt by the United States to enter a confrontation with China would further destabilize the multilateral system, including global health cooperation. More US funding for global health would go to national and bilateral channels, or supporting a smaller health agency that might exclude China and other rivals.

The theatrics may have overshadowed efforts by others in the Trump administration to raise genuine concerns about China’s responsibility for transparency during the early stages of the crisis. As underscored by Deborah Birx, coordinator of the White House coronavirus task force, any country first exposed to a pandemic, has “a higher moral obligation on communicating and transparency.” Whether China met that transparency test, she added, could be investigated once the pandemic subsides. China would likely resist any such multilateral investigation into its domestic affairs. Still, other nations could develop a framework, as she advises, and “figure out really what has to happen for first alerts and transparency and understanding very early on.”

The bottom line is that both the United States and China find the other’s conduct irresponsible and dangerous even as the world needs a norm of “responsibility to inform,” as much as a “responsibility to protect.”

.png) Rapid disruptors: Severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, offered a preview for Covid-19, but many nations did not prepare (Source: US CDC and Johns Hopkins Center for Systems Science and Engineering)

Rapid disruptors: Severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, offered a preview for Covid-19, but many nations did not prepare (Source: US CDC and Johns Hopkins Center for Systems Science and Engineering)

The multilateral system cannot address transnational threats like Covid-19 on its own. Such threats are linked to globalization, which cannot be entirely reversed. Pandemics emerged and spread during the Mongol Empire’s much smaller scale of globalization during the 14th century. That plague probably emerged in China before killing half of Europe’s population, then spreading on to India, Africa and the Middle East – eventually reducing the global population by almost 100 million.

As I wrote of the 2003 SARS crisis, the origins of pandemics cannot be regarded as exclusively external or internal to the region: “Rather, they emanate from external forces interacting closely with the internal vulnerabilities of states.” Hence, reducing internal vulnerabilities is a crucial first step.

Countries and territories that have done the early creditable work in containing Covid-19 were those that invested well in public health and early alert systems, after being devastated by SARS: Taiwan, Hong Kong, South Korea and Singapore – the latter experiencing a spike in new cases, mostly among migrant workers.

At the same time, highly exclusionary and inward-looking responses will not work in the long term and could impose severe economic costs. Closing national boundaries, as many nations have done, can only be a temporary measure. It’s noteworthy that SARS 2003 did not lead to such closures, mainly because of the disease’s lower transmissibility and absence of asymptomatic transmission, but also because the world was operating under a climate of trust and coordination with fewer populists.

Hence, old attitudes towards sovereignty and non-interference that prevent fact-finding and international monitoring must change, especially in countries like China that aspire to be leaders in global governance.

The multilateral system can also do better. For example, giving WHO more funding is not enough. Stronger mandates are also required. Instead of cutting funding and emasculating the organization, the United States and other nations should push for the UN Security Council to require mandatory reporting and allow WHO fact-finding missions within days of a major outbreak. National reporting on terrorism to the UN Security Council Counter-Terrorism Committee, now mandatory, could provide a model for pandemic preparations, with a shorter and incident-based reporting period.

The failure by any state to report outbreaks promptly and allow international fact-finding missions should be the equivalent of aggression. Most nations should readily agree after so many have endured thousands of human lives lost and trillions in economic losses.

Amitav Acharya is Distinguished Professor of International Relations, American University, Washington DC, and a 2019-20 fellow of the Berggruen Institute in California. He is the author of The Making of Global International Relations (Cambridge 2019); Constructing Global Order (Cambridge 2018); and The End of American World Order, 2nd edition (Polity 2018).

No comments:

Post a Comment