Charlie Dunlap, J.D

Last Friday the media reported that Navy leaders are recommending reinstatement for Captain Brett Crozier, the former commanding officer of the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt (Roosevelt) who was relieved from command for the way he handled the COVID-19 outbreak aboard his ship. This post examines a few leadership lessons that should be learned from his case.

Regrettably, the hagiographic narrative surrounding Captain Crozier is creating the very real risk that the wrong leadership lessons will be learned and propagated, irrespective of what does or does not happen to him personally. If that happens, the success of future military operations is imperiled, and troops could die. Some things really can be that simple.

To be clear, everyone agrees military leaders have the responsibility for the health and safety of those entrusted to them. Accordingly, Captain Crozier is to be rightly commended for being so concerned about the threat of COVID-19 to his crew. That doesn’t mean, however, that he handled his responsibilities the right way.

In this case, it’s especially important that we remind ourselves that despite all the accolades showered upon Captain Crozier, “no one will ever objectively know,” as a Navy officer notes below, “whether Captain Crozier achieved anything for his crew” by the actions that led to his relief.

Background

Before we examine some of leadership lessons that might be learned, let’s take a look at some available information. The most useful re-capitulation of the series of events is in the timeline found here assembled by Defense One’s deputy editor, Bradley Peniston – and I encourage you to review it.

In a nutshell, cases of COVID-19 began to appear on the carrier Roosevelt on March 22. On March 26, COVID-19 testing began for the entire crew, and Acting Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV), Thomas B. Modly, a Naval Academy graduate and former Navy pilot, reported that the Roosevelt would be docking at Guam, but only those needing treatment would be allowed to leave the pier.

Peniston says that on March 29th:

“Crozier and his superior officers are “struggling to reach a consensus on a plan of action, according to three people familiar with the discussions,” the Washington Post reported. “Among them were Rear Adm. Stuart Baker, who was embarked on the ship as its strike group commander, and Adm. John Aquilino, the commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. Both admirals favored smaller mitigation efforts than Crozier wanted because of concerns about taking the carrier out of action and jeopardizing the mission.”

Peniston relates the events of March 30 this way:

“[The SECNAV’s chief of staff] talks with Crozier by telephone, according to Modly, who said his staffer made it “very clear that if [Crozier] felt that he was not getting the proper response from his chain of command that he had a direct line into [Modly’s] office…The CO [Crozier] told my chief of staff that he was receiving those resources and he was fully aware of the Navy’s response, only asking that he wished the crew could be evacuated faster.”

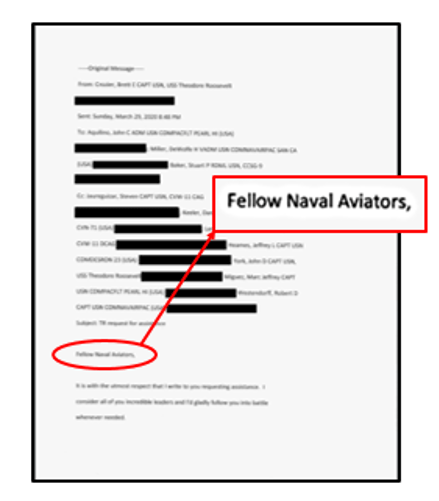

However, the very next day, a memo written by Captain Crosier appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle which headlined it as “Captain of aircraft carrier with growing coronavirus outbreak pleads for help from Navy.” The memo was attached to an email addressed to “Fellow Naval Aviators” and was sent (or copied) to several officers but, importantly, omitted the 7th Fleet commander (a non-aviator) who was responsible for overseeing the Roosevelt.

However, the very next day, a memo written by Captain Crosier appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle which headlined it as “Captain of aircraft carrier with growing coronavirus outbreak pleads for help from Navy.” The memo was attached to an email addressed to “Fellow Naval Aviators” and was sent (or copied) to several officers but, importantly, omitted the 7th Fleet commander (a non-aviator) who was responsible for overseeing the Roosevelt.

Moreover, the main addressee, “Rear Adm. Stuart Baker, the commander of the Roosevelt’s multi-ship strike group and Crozier’s immediate superior,” evidently was not consulted in advance. Washington Post columnist David Ignatius says:

“Baker told [Secretary of the Navy] Modly that he pressed Crozier why he hadn’t cleared the sensitive message or wide distribution group in advance. According to Modly, Crozier answered that “he worried Baker would not let him send it to that broad a group.” Baker affirmed to Modly: “He was right. I wouldn’t.”

Notwithstanding Captain Crozier’s email and memo indicating the Navy wasn’t moving fast enough to suit him, it does seem that the Navy was, in fact, working to move the sailors off the ship, but found there were practical issues to overcome. The Washington Post reports:

“A senior defense official acknowledged that Crozier wanted to remove sailors more quickly but said his effort wasn’t immediately realistic”.

“The problem was there was no place to put them at that time,” the senior defense official said. “The governor of Guam had started working with the hotel industry to get the hotels reopened. But that doesn’t happen overnight.”

After initially seeming to be tolerant and even approving of Captain Crozier’s actions, Secretary Modly decided to relieve him from command and did so on April 2.

(Parenthetically, “relief of command” does not expel an officer from the Navy, but rather is simply the characterization of the process when command changes. When it comes at the end of a normal tour – which was not the case here – it is not considered pejorative.)

In a statement worth reading (see here) Secretary Modly sought to explain his rationale. He pointed out that he was himself “both a parent and a veteran” and added:

In a statement worth reading (see here) Secretary Modly sought to explain his rationale. He pointed out that he was himself “both a parent and a veteran” and added:

“We all understand and cherish our responsibilities, and frankly our love, for all of our people in uniform, but to allow those emotions to color our judgment when communicating the current operational picture can, at best, create unnecessary confusion, and at worst, provide an incomplete picture of American combat readiness to our adversaries.”

Secretary Modly insisted that Captain Crozier “was absolutely correct in raising” his alarm, but took issue with Crozier’s methodology:

“It was the way in which he did this, by not working through and with his Strike Group Commander to develop a strategy to resolve the problems he raised, by not sending the letter to and through his chain of command, by not protecting the sensitive nature of the information contained within the letter appropriately, and lastly by not reaching out to me directly to voice his concerns, after that avenue had been provided to him through my team, that was unacceptable”.

But Secretary Modly was met with a firestorm of criticism the press, pundits, and anonymous sources within the Navy. In an effort to assuage at least some of that criticism, Modly visited the carrier Roosevelt to speak to the crew. Whatever his intentions, the visit went terribly awry, especially when Modly said Crozier was “too naïve or too stupid to be a commanding officer.”

Secretary Modly later apologized for his comments, but it was too late as influential politicians were already demanding his resignation. On April 7th Secretary of Defense Mark Esper accepted SECNAV’s resignation which Esper said was of Modly’s “own accord” and had been tendered to allow the Roosevelt and “the Navy as an institution” to “move forward.”

In moving forward, are there lessons to be learned. I think so, and here are some you may want to consider:

The lessons:

1) Senior military leaders should not assume a “peacetime” mindset in the midst of the risks intrinsic to 21st century “grey zone” conflicts.

The carrierRoosevelt was operating in what most experts consider to be a precarious part of the globe where every action is scrutinized by opportunistic adversaries ready to exploit any apparent weakness on the part of U.S. forces. It is hard to know the extent to which Captain Crosier might have – or have not – appreciated this reality.

Despite the brevity of his email and letter, Captain Crozier repeatedly contended that it was “peacetime” and that “we are not at war” – in a way he seemed to be almost trying to convince himself. Inexplicably, he never even acknowledges any of the serious threats to what he calls “peacetime” in the Pacific that should have provided context for his decision-making that affected the readiness of the USS Theodore Roosevelt Roosevelt. His civilian superior, Secretary Modly, saw it differently explaining:

“[T]here is a larger strategic context, one full of national security imperatives, of which all our commanders must all be aware today. While we may not be at war in a traditional sense, neither are we truly at peace. Authoritarian regimes are on the rise. Many nations are reaching, in many ways, to reduce our capacity to accomplish our national goals. This is actively happening every day.”

Although the U.S. hasn’t had a formal declaration of war since 1942, it nevertheless finds itself in a dangerous world that includes “grey zone conflicts” with near-peer powers like Russia and, especially, China.

In fact, the Pacific is something of a powder keg. In early January, the Council on Foreign Relations said “foreign policy experts ranked an armed confrontation over disputed maritime areas in the South China Sea between China and one or more claimants as a top conflict to watch in 2020.”

Indeed, China is capitalizing on the situation with the Roosevelt. A recent article in The Diplomat entitled “The Danger of China’s Maritime Aggression Amid COVID-19” warned how the pandemic was providing China with the opportunity to catch the U.S. and other countries “off guard”:

Indeed, China is capitalizing on the situation with the Roosevelt. A recent article in The Diplomat entitled “The Danger of China’s Maritime Aggression Amid COVID-19” warned how the pandemic was providing China with the opportunity to catch the U.S. and other countries “off guard”:

While most countries in the Indo-Pacific region are battling the coronavirus pandemic, China has been active in the South China Sea, taking aggressive action against Indonesia and Vietnam. China’s belligerent behavior, including military maneuvers and large-scale deployment of military assets to the region, have caught many of its neighbors and the United States off-guard, understandable considering their preoccupation with the pandemic in their respective countries.

Some experts connect such initaitives rather directly to Captain Crozier’s actions. Andrea Widburg contended in the American Thinker that: “[b]y going public with his complaints, Crozier essentially sent a giant banner up into the sky announcing to America’s enemies that one of the primary weapons in America’s arsenal might be out of commission.

China, may in fact, be emboldened enough to mock the U.S. Navy in the eyes of the world. A little more than a week ago, Newsweek reported that “China’s first aircraft carrier has sailed near disputed waters in the Pacific Ocean as the country’s state-run media praised the country’s military response to the novel coronavirus while it appeared to mock the United States’ struggle with it.”

China, may in fact, be emboldened enough to mock the U.S. Navy in the eyes of the world. A little more than a week ago, Newsweek reported that “China’s first aircraft carrier has sailed near disputed waters in the Pacific Ocean as the country’s state-run media praised the country’s military response to the novel coronavirus while it appeared to mock the United States’ struggle with it.”

And it’s not just China. Russia has been involved in several incidents recently in the Pacific area. Military.com reported on April 22 that “Russia is testing whether the U.S. military has developed any weaknesses during the novel coronavirus crisis” and notes that:

“Air Force F-22 Raptor fighter jets intercepted two Russian maritime patrol planes earlier this month approximately 50 miles from Alaska’s Aleutian Islands. About a month earlier, a pair of Russian reconnaissance aircraft were intercepted by U.S. and Canadian jets 50 miles from the state’s coast over the Beaufort Sea.”

Since the Roosevelt incident. Russia has shown its readiness to challenge the Navy elsewhere as well. On April 20, CNN reported that:

“US Naval Forces Europe-Africa/US 6th Fleet said in a statement Sunday the Russian aircraft, a SU-35 jet, “flew in an unsafe and unprofessional manner” while intercepting the US Navy P-8A Maritime Patrol and Reconnaissance Aircraft. The US Navy it said was the second time in four days that Russian pilots made unsafe maneuvers while intercepting US aircraft.”

I n yet another example of the alarming developments during a time that Captain Crozier characterizes as being “peacetime,” Reuters reported in late March that nuclear-armed “North Korea fire[d] more missiles than ever amid coronavirus outbreak.”

n yet another example of the alarming developments during a time that Captain Crozier characterizes as being “peacetime,” Reuters reported in late March that nuclear-armed “North Korea fire[d] more missiles than ever amid coronavirus outbreak.”

n yet another example of the alarming developments during a time that Captain Crozier characterizes as being “peacetime,” Reuters reported in late March that nuclear-armed “North Korea fire[d] more missiles than ever amid coronavirus outbreak.”

n yet another example of the alarming developments during a time that Captain Crozier characterizes as being “peacetime,” Reuters reported in late March that nuclear-armed “North Korea fire[d] more missiles than ever amid coronavirus outbreak.”

In truth, the Pacific is a tough neighborhood where adversaries are taking advantage of a major American weapons system like the Roosevelt being stuck in port.

Over-reliance on legalistic notions of what constitutes “war” can breed an alarming complacency and a diminished focus on the purpose for which the Roosevelt exists. Even if it is technically “peace,” it is a peace fraught with the risk of violence arising at almost any time, COVID-19 or not.

Military leaders who dismiss or diminish the risks grey zone conflicts present because they occur during a period officially characterized as “peace” put national security at great peril. They should never forget that the axiom that the “enemy gets a vote.”

2) Military leaders need to maintain situational awareness in a crisis.

Situational awareness (SA) has been described as “the ability to see what’s in the vicinity and anticipate what’s not — knowledge that can mean the difference between surviving or being killed in action.” In its most basic military form, “it is knowing what is going on around you” so as to avoid the many perils that inevitably present themselves to those in the armed forces.

SA is a principle that every military member needs to nurture, but especially those in command. It is a challenge to maintain it when one’s own emotions are high. Unfortunately, that may have been the case when Captain Crozier exited his ship after being relieved of his command by the Secretary of the Navy.

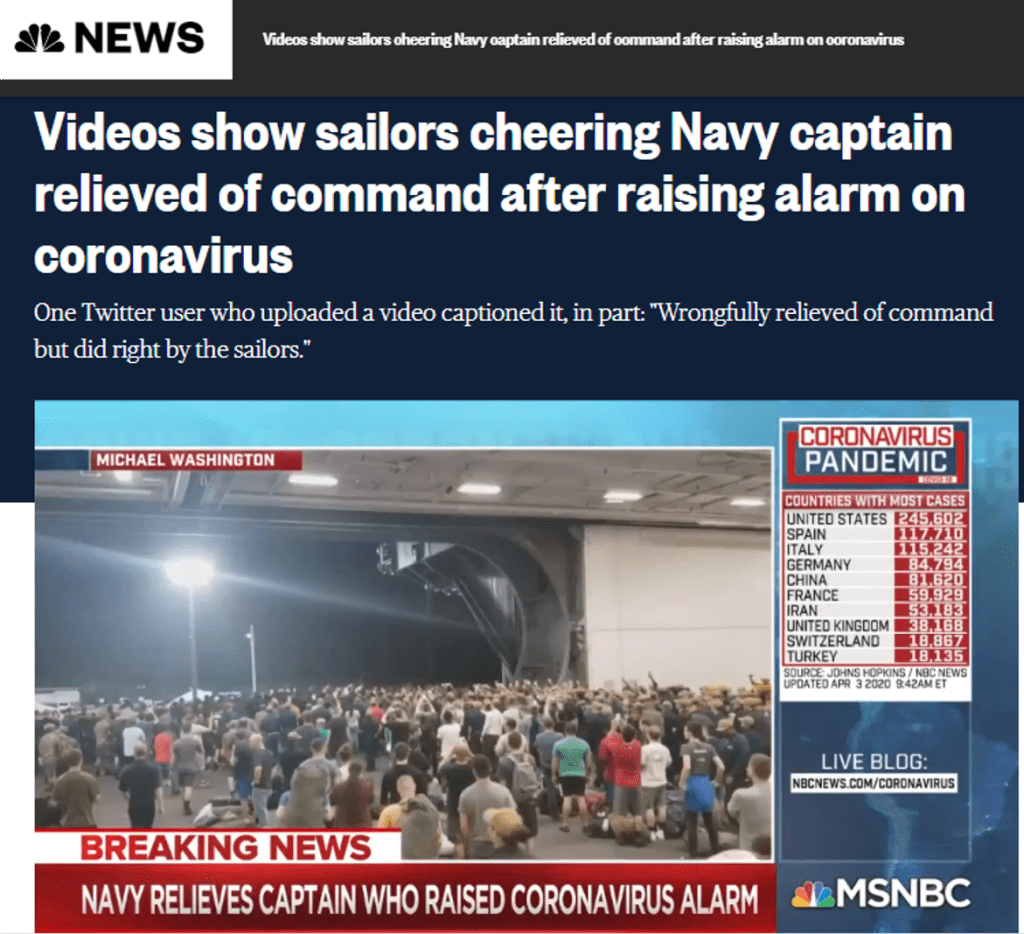

It is supreme irony that an officer who so forcefully insisted that the close quarters of his warship was life-threatening to his crew nevertheless tolerated hundreds of them – as the video found here shows – to crowd together to applaud him as he left the ship.

It is supreme irony that an officer who so forcefully insisted that the close quarters of his warship was life-threatening to his crew nevertheless tolerated hundreds of them – as the video found here shows – to crowd together to applaud him as he left the ship.

Notably, none of his officers or enlisted leaders appeared to try to break up the crowd even though they had the authority to do so if they wanted (and even if not in command, Crozier himself retained the authority to “quell…disorders”).

A former Navy warship commander described the situation in the Wall Street Journal this way:

“[W]hile Capt. Crozier recommended the crew be removed from his ship, it’s clear there was much they could have done but didn’t, as evidenced by their social-distance-be-damned rock-star departure celebration, which will likely leave them with more Covid-19 infections. The video suggests that the crew didn’t know—or worse, didn’t care—that their behavior was the naval equivalent of standing on top of a hill with bullets flying around them to generate an Instagram moment. Such behavior reflects poorly on their commander.”

“[W]hile Capt. Crozier recommended the crew be removed from his ship, it’s clear there was much they could have done but didn’t, as evidenced by their social-distance-be-damned rock-star departure celebration, which will likely leave them with more Covid-19 infections. The video suggests that the crew didn’t know—or worse, didn’t care—that their behavior was the naval equivalent of standing on top of a hill with bullets flying around them to generate an Instagram moment. Such behavior reflects poorly on their commander.”

We’ll never know how many (or, in fairness, if any) sailors might have been infected at the ill-disciplined event, but what we do know is that since that day an additional 700 members of the crew (including Crozier himself) have tested positive for the virus.

Again, maybe it was the emotion of the moment that clouded Crozier’s SA, but it is in exactly such times when a senior military leader needs to stay vigilant and attentive even if his subordinates don’t – or can’t – do so.

3) In crisis especially, military leaders need to be careful about the example they set in their civil-military relations.

Civilian control of the military was once thought to be so ingrained in the American psyche that few thought much about it. In this instance we may never know whether the way Captain Crozier handled his dispute with the Navy’s civilian leadership actually helped or hurt the well-being of his crew, but we do know that his disagreement with his civilian leadership set in motion events that led to the forced resignation of the civilian Secretary of the Navy.

Some may say the Secretary got justice for the unquestionably ham-handed way he handled his visit to the Roosevelt to explain Captain Crozier’s relief from command. Maybe so, but we need to be concerned about the example – and precedent – the actions by Captain Crozier set for others.

Decide for yourself: did Captain Crozier know (or reasonably should have known) that his unclassified email and memo deriding the Navy’s efforts to address the situation aboard his ship would reach the public? If so, is that the way we want senior leaders to handle disagreement with civilian superiors? In any event, the cascading effect of Crozier’s actions was to deny the Navy the opportunity to manage the crisis in its civilian leader thought best for the service writ large. Here’s how retired Navy Captain Kevin Eyer analyzed the the situation on the U.S. Naval Institute’s blog:

“Captain Crozier precipitated the removal of one of the Navy’s few, most powerful strategic assets from the playing board. This hole cannot be filled without machinations that leave other holes and drag thousands of sailors back to long deployments early. The Navy was not allowed to work to a strategic “soft-fall,” and our potential enemies were given a wrong signal. That, if nothing else, cannot be forgiven.”

“Captain Crozier precipitated the removal of one of the Navy’s few, most powerful strategic assets from the playing board. This hole cannot be filled without machinations that leave other holes and drag thousands of sailors back to long deployments early. The Navy was not allowed to work to a strategic “soft-fall,” and our potential enemies were given a wrong signal. That, if nothing else, cannot be forgiven.”

In his statement at the time of Captain Crozier’s relief, Secretary Modly was clearly bothered by the seeds of doubt about the Navy and its leadership Captain Crozier’s missive seemed to plant in the minds of the public, not to mention those in uniform:

“It was sent outside the chain of command, at the same time the rest of the Navy was fully responding. Worse, the Captain’s actions made his Sailors, their families, and many in the public believe that his letter was the only reason help from our larger Navy family was forthcoming, which was hardly the case.”

It is simply wrong to imply that Captain Crozier’s seniors were any less concerned about the health and safety of his crew than he was. Yes, Crozier was directly responsible for his 4,800-person crew, but Navy senior leaders are accountable for more than 347,000 sailors.

This incident could make civilian leaders understandably doubt whether they can still trust military leaders, particularly when they come to conclusions at odds with those of their uniformed subordinates. Conversely, as a retired officer pointed out to me, the equal danger is it’s potential to foster military distrust of civilian leadership. Such doubts and mutual distrust can damage the kind of civil-military relations America needs to fact the multiple threats we see today.

Furthermore, there is no evidence that anything the Navy was doing or wanted Crozier to do was unlawful. Simply because a subordinate thinks he has a better plan doesn’t mean he can try to undermine the process his superior has decided upon. Keep in mind the Manual for Courts-Martial provides that “the dictates of a person’s conscience, religion, or personal philosophy cannot justify or excuse the disobedience of an otherwise lawful order.”

Furthermore, there is no evidence that anything the Navy was doing or wanted Crozier to do was unlawful. Simply because a subordinate thinks he has a better plan doesn’t mean he can try to undermine the process his superior has decided upon. Keep in mind the Manual for Courts-Martial provides that “the dictates of a person’s conscience, religion, or personal philosophy cannot justify or excuse the disobedience of an otherwise lawful order.”

Captain Crozier seemed to believe he was entitled to circumvent the staffing procedures the Navy employs for emergencies. Consider that in the 1983 case of Chappell v. Wallace the Supreme Court warned:

“The inescapable demands of military discipline and obedience to orders cannot be taught on battlefields; the habit of immediate compliance with military procedures and orders must be virtually reflex, with no time for debate or reflection.”

Again, many may revel in Captain Crozier’s supposed “victory” over his civilian leader, but the way he handled this incident cannot help but to erode the trust and mutual confidence that underpins effective military-civilian relations. This is no doubt a reminder to civilian leaders that a shrewd military officer might be able to leverage the public’s affection and trust for those on the armed forces against them. Civilian leaders just don’t enjoy the same popularity with the citizenry.

Indeed, it very well could be that the public adulation Crozier accrued will serve to entice – or, perhaps worse, pressure – other military officers to do something similar. In fact, if other commanders don’t publically speak out demanding special treatment for his or her units in the face of lawful direction with which he or she disagrees, it might seem to subordinates that their commander doesn’t care about them. That consequence has serious implications for military morale and discipline.

To reiterate, appropriate and productive civil- military relations won’t exist in a democracy if military officers begin to assume Captain Crozier’s methodology is the clever way of addressing differences with civilian leaders as to how to deal with a complex problem. We should not want a system where civilian leaders come to expect that military subordinates will seek to circumvent them by appealing to the public when they dislike the direction the civilian leadership has determined is best.

4) In crisis situations, leaders need to think inclusively in terms of the organization as whole and not about particular career fields.

The now famous memo Captain Crozier wrote complaining that the Navy’s response to the COVID-19 outbreak on his ship was, in his view, inadequate, was itself curiously unaddressed.

However, it was attached to an email that was, but didn’t use an inclusive address such as “Sailors,” but instead directed it only to a select sub-faction in the Navy: “Fellow Naval Aviators.” Notably, it omitted Vice Adm. William Merz, a career submariner, but the officer “who oversaw the Roosevelt as commander of the Navy’s 7th Fleet.”

However, it was attached to an email that was, but didn’t use an inclusive address such as “Sailors,” but instead directed it only to a select sub-faction in the Navy: “Fellow Naval Aviators.” Notably, it omitted Vice Adm. William Merz, a career submariner, but the officer “who oversaw the Roosevelt as commander of the Navy’s 7th Fleet.”

To civilians this may not mean much, but within the Navy it has real significance. The Navy has long been divided into a “brown shoe” culture of aviation officers and a “black shoe” culture of surface officers. Increasingly, this divide is not serving the Navy well. Reflecting on the “surface navy’s catastrophes in 2017,” two Navy lieutenants wrote:

“We’ve had enough of the “brown shoe,” “black shoe” cultural conflict in our navy, and it’s not just a surface – aviation divide. The real travesty is that the Navy’s community culture has created silos of knowledge, and in fact, overt hostility to those who are nominally our brothers and sisters in arms. It is this culture that ultimately led to a surface community searching for answers after a terrible 2017, when in fact the answers sat literally across the street in the Navy’s own aviation community. It is a moral travesty that it took the death of seventeen Sailors to force a reckoning in the SWO [surface warfare officer] community, but we’re there.“

At that time, the lieutenants were criticizing the SWO community for excluding the aviation community in the search for answers to a crisis manifested by a troubling series of ship collisions. Crozier seems to have made the same mistake, but in reverse, that is, addressing the issue as if only “Fellow Naval Aviators” would be concerned about the lives of sailors and embarked Marines, and only aviators could provide answers.

The Navy has long sought to counter such a divisive approach by advocating a “one team, one fight” attitude, but the Crozier email indicates that at best, he did not internalize that mindset. Actually, in times of complex crises involving diverse persons especially, leaders need to be inclusive in their thinking as solutions may come from beyond their own discrete career field.

It is unknowable if this episode would have come to a better end if, for example, Captain Crozier had sought to address his concerns through his commander at 7th Fleet instead of omitting him in favor of a collection of “Fellow Naval Aviators.” Still, putting aside the specific issues as to the propriety of Captain Crozier’s actions in the first place, it is well worth remembering that siloed advice is almost by definition going to be inferior to that produced by a process that brings to bear a range expertise on complicated problems.

5) In crisis situations, leaders need to put aside concerns about their own careers.

Captain Crozier concluded his email to his “Fellow Naval Aviators” by telling them that he was taking his action “regardless of the impact on [his] career.” In point of fact, it was hardly necessary to tell experienced senior officers to whom he addressed his email with its incendiary attachment about the potential career fallout from the way he elected to deal with the crisis.

Circumventing what Captain Crozier derided as mere “normal staffing processes” (that would have included his immediate commander at 7th Fleet) in what was a sensitive and high-profile matter being personally worked by the SECNAV rather obviously could have highly-adverse personal consequences for any officer in almost any situation.

Captain Crozier’s exact motivation for including a reference to his own career isn’t clear. Was he hoping to prompt his “Fellow Naval Aviators” into protecting him from the wrath of the Navy’s non-aviator leadership? Did he have a sense that the COVID-19 infection came from his ”Fellow Naval Aviators” as the Wall Street Journal would later indicate and wanted to cast his community as the solvers of the problem and not the source of it? Was he anticipating his email would eventually reach the public, and wanted to ennoble himself in their eyes?

Regardless, when leaders allow themselves to articulate fears about their own career prospects in the midst of a crisis where other lives are at stake, it undermines the altruism of the message they ought to be seeking to convey.

6) Senior leaders, especially in complex emergencies, need to communicate in an effective way, and understand their options if they believe their concerns are being wrongly ignored.

According to a thoughtful and rather detailed analysis of Captain Crozier’s memo by Navy Captain Anthony Cowden, “there are effective ways of “speaking truth to power” but Crozier’s memo “was not one of them.” Cowden concludes by saying:

“[E]ffective writing should achieve the desired results without contributing to the author being relieved of his command. While many will express opinions on the subject, the fact is that no one will ever objectively know whether Captain Crozier achieved anything for his crew in writing this memorandum other than THEODORE ROOSEVELT getting a new commanding officer.”

“[E]ffective writing should achieve the desired results without contributing to the author being relieved of his command. While many will express opinions on the subject, the fact is that no one will ever objectively know whether Captain Crozier achieved anything for his crew in writing this memorandum other than THEODORE ROOSEVELT getting a new commanding officer.”

Moreover, the popular narrative seems to suggest that Crozier was left with no other options to lodge his complaints. Cowden suggests some in his analysis, but there are others.

For example, Crozier could have framed his complaint under the Military Whistleblower Act and made a “protected disclosure.” In addition, Crosier could have made a complaint under Article 138 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (10 U.S.C. § 938). Crozier’s embarked staff judge advocate could also have conveyed his concerns directly to the Navy’s Judge Advocate General per 10 U.S. Code § 806 (b).

7) Commanders (as well as the media and the public) shouldn’t confuse popularity with good leadership.

As noted above, the media has been quick to point out that after being relieved Captain Crozier was cheered by hundreds of fawning sailors as he left the ship, and they were making their way to being ensconced in Guam’s tourist resorts and spas for quarantine. (In contrast, the Army quarantined troops returning from Afghanistan in field conditions.)

Regardless, it’s axiomatic that great leadership is not a popularity contest. For example, during the Civil War both sides suffered from commanders who were well-liked by their subordinates but terrible as military leaders. Union general George McClellan was popular by his troops but is rated as one of the worst generals in history.

Writing in the New York Times in 2011, Professor Terry L Jones said that Confederate general Leonidas Polk’s military career was marked with “poor performance” and charged him with making “one of the greatest military blunders of the war” by occupying Columbus, Kentucky. Jones explained how Polk nevertheless managed to keep his command:

“Part of his staying power is attributable to his popularity among rank-and-file soldiers. Regal and elegant, he looked like a successful general and was always affable and caring of his soldiers.”

Most people welcome popularity, but an Army officer gave this caution in 2017:

“[A]nyone who has been in command or who has been in charge of something knows how difficult it can be to get things done. The timeless phrase of “leadership is not a popularity contest” is constantly extolled as a guideline. Leaders should look after their people, their property, and accomplish the mission — sometimes that means doing things the followers do not like or understand.”

Interestingly, distinctly unpopular leaders can still be enormously effective. Admiral Hyman Rickover. who was characterized during his life as one of the “most unpopular admirals in the Nayy,” nevertheless achieved greatness by introducing nuclear power to the Navy, which transformed it into the global force it is today.

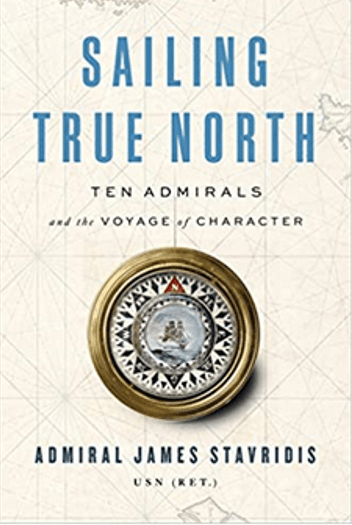

In his masterful book on leadership, Sailing True North: Ten Admirals and the Voyage of Character, my War College classmate, Admiral Jim Stavridis, profiled Rickover. He laid out Rickover’s petulant and irascible personality, but also pointed out how Rickover’s relentless work ethic and unstoppable determination allowed him to become the “Father of the Nuclear Navy.”

In his masterful book on leadership, Sailing True North: Ten Admirals and the Voyage of Character, my War College classmate, Admiral Jim Stavridis, profiled Rickover. He laid out Rickover’s petulant and irascible personality, but also pointed out how Rickover’s relentless work ethic and unstoppable determination allowed him to become the “Father of the Nuclear Navy.”

In another fabulous leadership book, Call Sign Chaos: Learning to Lead, General Jim Mattis makes this observation worth pondering in assessing the current case:

“Building trust and affection in units is not the same thing as chasing popularity, which relies on favoritism, nor does it replace the priority of accomplishing the mission. For this reason I came down hard on anyone who said, “Sir, my mission is to bring all of my men home safely.” That is a laudable and necessary goal, but the primary mission was to defeat the enemy, even as we did everything possible to keep our young men and women alive.”

Captain Crozier’s concern about his crew is likewise laudable and resonated with his juniors as well as with many other audiences but – again – the point is that popularity with subordinates (or, for that matter, with the public) is not necessarily the right barometer with which to measure effective military leadership.

8) Don’t trivialize potential civilian casualties as a mere “political” problem.

In his email, Captain Crozier declared that “at this point [his] only priority is the continued well-being of the crew and the embarked staff.” However, when civilian lives are also at risk the well-being of his own unit can never be a military commander’s “only priority.”

Is the potential of civilian casualties really simply a matter of “politics”? In his campaign to get his crew into civilian tourist hotels, Crozier variously dismissed the challenges involved as merely a “political concern” or simply something requiring a “political solution.” On April 1, a local elected official wrote Guam’s governor saying:

“I am disturbed by the reckless double-standard of potentially placing potentially exposed military personnel in local hotels…If sailors are placed in our hotels, we will be exposing lower-wage employees to greater risk, many of whom are older and have limited or no health benefits for themselves and their families.”

The Navy did eventually make arrangements where local workers would not have direct contact with the quarantined sailors, but health concerns remained, even as many Guamanians did support lodging the sailors. For example, the Diplomat reported on April 13th that Guam “has underlying health issues and a history of economic and political challenges that make fighting the coronavirus difficult.” It then said:

“Dr. Lisalinda Natividad, a social work professor at the University of Guam, points to the island’s elevated rates of noncommunicable diseases like diabetes, cancer, and heart disease as complicating factors. She says many are already living close to the poverty line, and the healthcare system is ‘insanely fragile’ and fragmented.”

These underlying health conditions put many Guamanians in the high-risk category for COVID-19. In contrast, Captain Crozier’s crew – being young and healthy – was mostly in the very low risk category. Although tragically one crewman did pass away from the virus (the Navy had removed him from the ship prior to Crozier’s letter), of the 17% who did test positive, 60% of them suffered no symptoms, and of those who did, almost all of the symptoms were mild (as of this writing only four were hospitalized, and none are in intensive care).

That Captain Crozier’s crew was at such low risk fits with Department of Defense statistics from across the services which is far lower than the civilian rate. MilitaryTimes.com reports that overall “DoD’s death rate is at 0.4 percent versus the overall U.S. rate of 5 percent.” (Of course, those figures for both DoD and the U.S. are fluctuating – and the overall death rate on Covid-19 is expected to be much lower, and will only be correctly judged once compared against all those who apparently had the illness but have not yet been tested.)

The markedly lower threat of COVID to Captain Crozier’s young, healthy crew that we know about now, undercuts his repeated comparison of his warship to the civilian cruise ship, the Diamond Princess. The Diamond Princess –with 3,700 passengers and crew aboard – had many more people than the Roosevelt in the high-risk category (older passengers with underlying health conditions). The median age of those hospitalized with the virus was 75. Nine died.

Sure, the Diamond Princess’ passengers (but not crew) were able to quarantine in their cabins – something few of the Roosevelt’s crew could do as Captain Crozier pointed out. However, the Diamond Princess suffered only a slightly higher infection rate (19% v. 17%) than did the Roosevelt, so it’s not clear what advantage – if any – the cabins provided.

A sailor tests a gas mask during a Chemical, Biological and Radiological equipment test aboard the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt in 2008.

A sailor tests a gas mask during a Chemical, Biological and Radiological equipment test aboard the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt in 2008.

Moreover, Crozier’s warship, unlike the cruise ship, was organized, trained, and equipped to function in a chemical, biological, or radiological environment. Plus, the Roosevelt had real-world experience having had a virus outbreak in 2002 that struck hundreds of sailors.

In short, no commander in the 21st century ought to dismiss the potential of civilian casualties in any kind of operation as just being something needing a “political solution.”

Concluding observations:

On Saturday the media reported that the Pentagon was still grappling with the question as to whether or not Captain Crozier ought to be reinstated as Navy officials are recommending. Apparently, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Mark Milley wants” “a ‘full-blown investigation’ into the events leading up to the Crozier’s ouster” before making his recommendation.

That would seem wise. The Navy has had a number of issues over the last few years that raise questions of morale, discipline and readiness (see, e.g., here, here, and here). Both General Milley and Secretary Esper need to determine if this incident is a “one off” or yet another manifestation of deeper problems. The $4.5 billion Roosevelt and its nearly 5,000 person crew are simply too vital to the nation not to be absolutely confident about its leadership.

Of course, it cannot – and should not – be an easy decision when it involves an officer with what we can presume to be an otherwise fine record. In his book General Mattis recounts when he had to relieve a commander who was advancing against the enemy at too slow and cautious a pace. When Mattis asked why he wasn’t pressing harder, the commander’s answer surprised him.

Of course, it cannot – and should not – be an easy decision when it involves an officer with what we can presume to be an otherwise fine record. In his book General Mattis recounts when he had to relieve a commander who was advancing against the enemy at too slow and cautious a pace. When Mattis asked why he wasn’t pressing harder, the commander’s answer surprised him.

Mattis said the officer “expressed his heartfelt reluctance to lose any of his men by pushing at what might seem to be a reckless pace.” Mattis was “torn by his answer” and explained:

“I want officers to nurture a deep affection for their men, as I do – in my view, it’s fundamental to building the trust that glues an organization together…I also understood how difficult it is to order men you’ve come to love into a fight that some won’t survive. But the mission must come first.”

What did Mattis do?

“On the spot, I relieved the…commander, a noble and capable officer who in past posts had performed superbly. But when the zeal of a commander flags, you must make a change.”

It would appear that Captain Crozier had zeal, but the question for General Milley and, ultimately, Secretary Esper, was whether the zeal was the right kind, and was it properly expended? Or was Secretary Modly correct that Captain Crozier lacked sufficient appreciation for the “larger strategic context” and competing “national security imperatives”? Did emotion make him too impatient about the pace of the Navy’s actions, and the leadership of civilian superiors? Did he allow adversaries to seize the initiative in grey zone conflicts? Did he overestimate the risk to his crew, and underestimate the risk to civilians?

Overall, did Captain Crozier make the right decision for the Navy and, more importantly, the nation? To be clear, Captain Crozier insisted that he was ready to take his ship into combat and fight adversaries if at “war”, but to what extent is he prepared to take risks to wage grey zone “war” when that’s the mission in our complicated world?

The stake are high as our adversaries are closely watching how the U.S. military deals with the pandemic. Retired special forces colonel David Maxwell, now a senior fellow with the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, shared this sober and unvarnished observation:

“[W]e need to learn how to “fight through” this pandemic just as if it is a biological attack. Our adversaries are observing and analyzing our actions and assessing the potential efficacy of using biological weapons against us, especially in the “gray zone” of great power competition. If they assess this pandemic kicks our 4th point of contact they will be more likely to use bio weapons in the future.”

It’s hard to know what Captain Crozier himself thinks as he reflects on what’s transpired. When Secretary Modly botched his visit to the Roosevelt, he concluded that his resignation would best serve the Roosevelt and the larger interests of the institutional Navy. Evidently, Captain Crozier has drawn no such conclusions about himself, or the value of his continued service.

Regardless of the disposition of Captain Crozier’s case, it’s imperative that the entire incident be evaluated to see what lessons can be learned. This post suggests some, but there are certainly more. If we can distill this episode to build better leaders in the future, it will serve to further strengthen the Navy, the Armed Forces, and our national security, particularly in times of crisis.

Still, remember our Lawfire® mantra: gather the facts, examine the law, evaluate the arguments – and then decide for yourself!

No comments:

Post a Comment