By: Sergey Sukhankin

Introduction

In addition to the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) Support Base in Djibouti, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has indicated ambitious plans for future “strategic strong point” naval bases in the Indian Ocean and Africa (China Brief, March 22, 2019), and has pursued this goal with varying degrees of success (China Brief, April 13). One of the key ideas behind these bases is to provide security to Chinese workers and businesses abroad. By late 2016, more than 30,000 Chinese businesses had invested offshore (with a total investment of $1.2 trillion) and nearly one million Chinese citizens were working abroad (China Daily, July 14, 2017). Many of these workers are either employed, or in the near future could be employed, along Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) routes that traverse over some of the world’s most unstable and dangerous areas (China Brief, February 15, 2019; China Brief, April 1).

The PRC has sought multiple means to improve regional security in BRI-affiliated countries, to include promoting a greater role for the Central Asia-based Shanghai Cooperation Organization (China Brief, July 16, 2019). The PRC has also sponsored the “Beijing Xiangshan Forum” (北京香山论坛, Beijing Xiangshan Luntan) which has been promoted as “the security component” of the BRI, and as a cooperative framework intended to strengthen military-technical cooperation with BRI-associated countries (Belt and Road News October 28, 2019; China Brief, November 19, 2019).

However, traditional means of security assurance do not always correspond to the new realities and the new needs of China’s increasing overseas presence. In this evolving environment, other instruments—to include the growing Chinese private security industry—are attaining a crucial role. Previous work by this author has detailed many aspects of the growing use of Russian private military companies in unstable regions and conflicts throughout the world (Jamestown, multiple dates). This article seeks to provide insights into the growth of China’s private security industry, which to date has not been as closely examined.

Chinese PSCs in Transition: The Milestones

The development of Chinese private security companies (PSC) has been shaped by tragic incidents involving Chinese nationals abroad. First emerging in the 1990s, Chinese PSCs became more prominent after 2004, when 11 Chinese construction workers were killed in Afghanistan by the Taliban (China.org.cn, June 10, 2004). Following a series of subsequent incidents in East Timor, Chad, Lebanon, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Thailand, Haiti, and later Libya and Egypt, the necessity to protect Chinese nationals abroad became a more pressing necessity. These incidents involving Chinese nationals resulted in the rapid rise of the Chinese PSC industry.

In September 2009, the PRC State Council issued the “Regulation on the Administration of Security and Guarding Services” (保安服务管理条例, Baoan Fuwu Guanli Tiaoli). This measure was the PRC’s first attempt to establish a regulatory framework for the private security industry, and gave de facto legalization to PSCs. The regulation recognized two main types of PSCs: “security companies” (保安服务公司, baoan fuwu gongsi), and “security companies engaged in armed escorting services” (从事武装守护押运服务的保安服务公司, congshi wuzhuang shouhu yayun fuwu de baoan fuwu gongsi). The regulation provided a basic legal framework for PSCs operating domestically within China, but made no clear reference to overseas activities (Law Info China, October 13, 2009).

By the time the BRI was formally announced in 2013, 4,000 entities employing more than 4.3 million security personnel were registered in China (Asia Sentinel September 3, 2018). This year was also marked by the beginning of Erik Prince’s involvement in the Chinese PSC industry via the creation of Hong-Kong registered Frontier Services Group (FSG) (先丰服务集团, Xianfeng Fuwu Jituan). [1] Later, Prince explicitly stated that FSG would be oriented towards providing logistical assistance and security training to Chinese businesses and government personnel working on BRI projects (Global Times, March 21, 2017).

Between 2014 and 2016, a series of international incidents in Iraq and South Sudan required the evacuation of Chinese nationals. These incidents directed international attention to two Chinese PSCs in particular: VSS Security (伟之杰安保公司, Weizhijie Anbao Gongsi) and DeWe Security (北京德威保安服务有限公司, Beijing Dewei Baoan Fuwu Youxian Gongsi). This also resulted in a 2016 statement by Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary Xi Jinping on the necessity to render all necessary protection to Chinese companies working in dangerous regions. By 2016, the overall number of Chinese PSCs working abroad rose to twenty, with 3,200 security professionals deployed overseas (Global Times, June 23, 2016; China Daily April 22, 2016). However, the international market share of Chinese PSCs remained miniscule in comparison with their Western counterparts. Image: Personnel of the private security firm Bojing Tewei (博警特卫) conduct martial arts and bodyguard training (undated, circa 2016). (Source: CGTN/Youtube)

Image: Personnel of the private security firm Bojing Tewei (博警特卫) conduct martial arts and bodyguard training (undated, circa 2016). (Source: CGTN/Youtube)

Image: Personnel of the private security firm Bojing Tewei (博警特卫) conduct martial arts and bodyguard training (undated, circa 2016). (Source: CGTN/Youtube)

Image: Personnel of the private security firm Bojing Tewei (博警特卫) conduct martial arts and bodyguard training (undated, circa 2016). (Source: CGTN/Youtube)

New Developments in 2019

The year 2019 was marked by several important transformations within the Chinese PSC industry, to include a trend towards increasing professionalism. Early 2019 saw the announcement that Frontier Services Group would create a “training base” in the Xinjiang region, with the company pledged to invest $600,000 in a center capable of training 8,000 people per year (Sputnik News, February 1, 2019). When asked about this, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang declined to give any comments (SCMP, February 1, 2019).

The issue of PSCs also entered into the PRC’s domestic discourse in 2019. Speaking at the annual Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference in March 2019, CITIC Capital Holdings Ltd. Chairman Zhang Yichen made a number of comments about PSCs, including the following:

China needs to drastically increase budgetary spending on the security of its overseas embassies and key infrastructural projects—to include further funding for Chinese private security forces, whose capabilities should be upgraded to the level of their Western counterparts;

Coordination between government departments and private security firms should be strengthened;

A national fund with a focus on overseas security projects should be established;

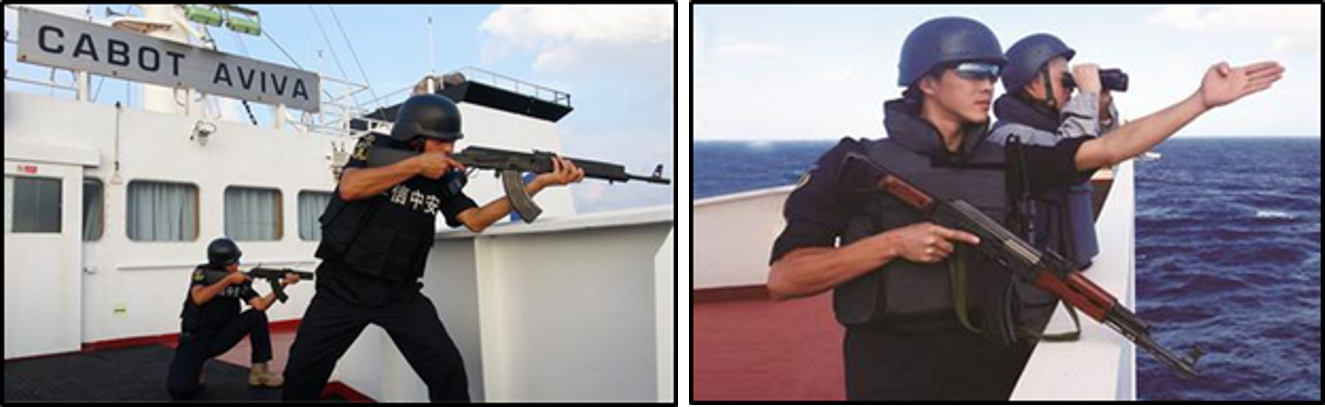

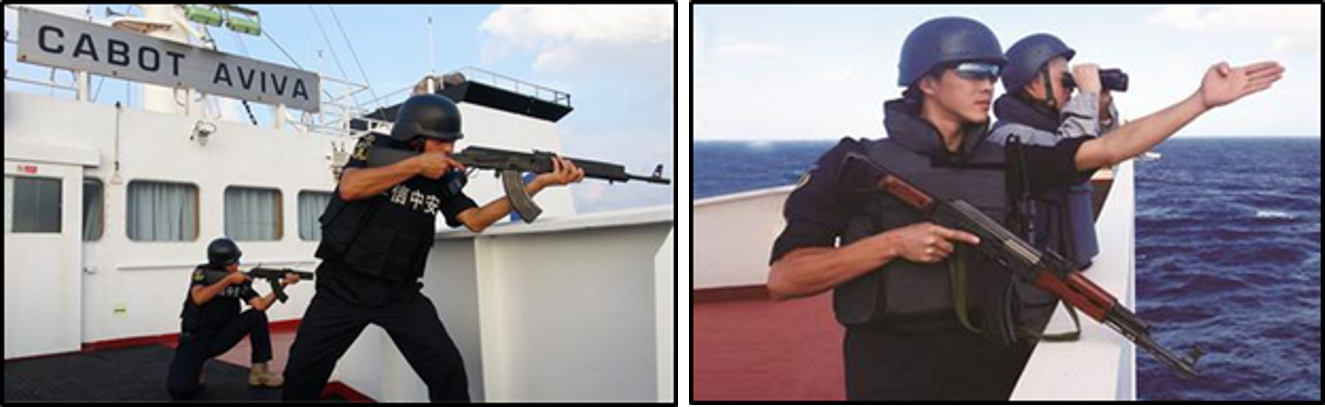

The Beidou (北斗) satellite navigation system should be relied on, which will “allow Chinese companies to acquire a massive amount of security information in overseas markets without relying on Western technologies” (Belt and Road News, March 10, 2019). Images: Publicity photos from the Chinese private security contractor Hua Xin Zhong An (华信中安), advertising the capabilities of the company’s shipboard security personnel. (Source: Hua Xin Zhong An)

Images: Publicity photos from the Chinese private security contractor Hua Xin Zhong An (华信中安), advertising the capabilities of the company’s shipboard security personnel. (Source: Hua Xin Zhong An)

Images: Publicity photos from the Chinese private security contractor Hua Xin Zhong An (华信中安), advertising the capabilities of the company’s shipboard security personnel. (Source: Hua Xin Zhong An)

Images: Publicity photos from the Chinese private security contractor Hua Xin Zhong An (华信中安), advertising the capabilities of the company’s shipboard security personnel. (Source: Hua Xin Zhong An)

What are Chinese PSCs, and Whose Interests Do They Serve?

Among Sinologists who have studied the topic, viewpoints on Chinese PSCs—regarding both their levels of professionalism, and the extent of their ties to the state—vary widely. Alessandro Arduino contends that Chinese PSCs are “neither an extension of the PLA nor an armed wing of the Chinese Communist Party,” and views them as underdeveloped, privately-run enterprises (The Diplomat, March 20, 2018). Alexey Maslov, head of the School of Asian Studies at the Higher School of Economics (HSE) in Moscow, has argued that Chinese PSCs “are not very effective and quite unprofessional,” and that “there is no concrete proof that these companies are somehow related to the Chinese state” (Current Time.tv, February 2, 2019).

Another Russian source, however, maintains that “Chinese PMCs are hardly market players… They are created by former military and police personnel and controlled by state bodies, whereas their clients are large state corporations” (Ria.ru, March 23, 2017). A similar conclusion was made by the Mercator Institute for China Studies, which argued that “Chinese PSCs are entirely under the control of the state, through the Ministry of Public Security (MPS).” [2] It is the author’s own opinion that, based on available references, statements of notable Chinese figures, and PRC political traditions, it is unlikely that Chinese PSCs operate independently of the state.

Focused on the BRI Africa (strategic coop-eration agreement with the Australian MSS Security Group) Argentina, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Iraq, Jordan, Sri Lanka, Laos, Indonesia,Pakistan, Turkey, Malaysia, Cambodia, Mozambique, South Africa and Thailand. Focused on the BRI Overseas operations (up to 50 countries) Focused on East Africa, Northwest, Southwest and Middle East & North Africa.

Hdqtrs. in Hong Kong and Beijing; offices in Shanghai, Dubai, Nairobi, Boten, Malta,Johannesburg. Nationwide; focus on the BRI Focused on the Chinese market (33 branches, 1 security training school and 12 security training branches)

(Source: Compiled by the author)

Chinese PSCs: Weaknesses and Challenges

Despite its growth, the Chinese PSC industry continues to face challenges—with three issues standing out in particular. The first is the lack of a legal framework: while Chinese PSCs have a legal status for operations inside China, they lack clear guidelines for international operations. This stems from the “Law of the PRC on Control of Guns” (中华人民共和国枪支管理法, Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Qiangzhi Guanli Fa) adopted in 1996, which allows only the PLA, the police, and the militia to possess weapons (China.org.cn, February 14, 2011). Furthermore, according to PRC criminal statutes, those who possess weapons overseas may face imprisonment. As stated by a security guard who worked at an oilfield in Iraq, Chinese PSCs operating abroad are unable to effectively protect themselves and their clients, and are limited to reporting potential threats to local police (Global Times January 23, 2015). Thus, while operating abroad, many Chinese businesses actually prefer to employ Western PSCs.

Second, deficiencies exist in training and qualifications. As noted by Tian Buchou, a veteran of the Chinese special forces who worked in private security in the Middle East and Africa, in terms of training and expertise Chinese PSCs are far behind their Western counterparts, which have a “comprehensive operational system covering logistics, weapons, high-technology and even medical support”, whereas “more than 80 per cent of Chinese security personnel have just a basic education” (SCMP July 15, 2018). He also identified the lack of knowledge of foreign languages among Chinese PSC personnel, and a reluctance to learn new skills. Another serious issue is low pay, and the fact that Chinese PSC members “are paid by the mission without other benefits.” This greatly affects the prestige and desirability of jobs with PSCs (SCMP, July 16, 2018).

The third aspect presents a far more complex issue: the activities of Chinese PSCs abroad, and potential complications surrounding the right to carry lethal weapons, are likely to result in incidents that could aggravate negative perceptions of China in developing countries. Specifically, incidents involving Chinese PSCs in Zambia in 2010 and South Sudan in 2012 caused a huge uproar. Moreover, the example of Pakistan—where the PRC has tried to use its PSCs to protect its economic interests along the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), but saw them pushed out—clearly demonstrated that many countries are reluctant to have Chinese paramilitary personnel on their soil (Reuters, August 19, 2012).

Conclusion: What Happens Next?

Despite challenges associated with its PSC industry, the PRC is bound to take further steps to support this industry for two main reasons. First, the growing global presence of Chinese businesses will require protection—which, given China’s image and ambitions, excludes permanent reliance on foreign PSCs. Secondly, China has a large number of military veterans—57 million as of 2018, with growing discontent among this group (China Daily, March 14, 2018)—and PSCs may provide a means of employment for some of these veterans.

The Chinese are analyzing their foreign experiences and evaluating the different models available on the market. The Western model is premised on full legalization; use of force as an extreme measure; greater transparency and openness to domestic and international scrutiny; and independence from the state. However, this model presumes greater transparency and a larger role for private ownership—elements that are likely unpalatable for the Chinese government. The Russian model, by contrast, is predicated on near complete dependency on the state; illegal status and next to zero accountability for actions; and plausible deniability that could be enjoyed by the state and sponsors of these entities (War by Other Means, March 20, 2019). This pattern, however, carries the risk of negative international publicity, and requires personnel with extensive fighting experience—an element that the Chinese military, unlike its Russian counterpart, does not have.

Most likely, the Chinese model will differ from both patterns. Legalized entities are likely to remain under tight control of the state, which will allow the Chinese government to use its PSCs to promote Beijing’s geopolitical and economic interests in strategically important areas. As the PRC’s economic presence continues to expand overseas, China’s growing private security industry is likely to follow in its stead.

Dr. Sergey Sukhankin is a Fellow at the Jamestown Foundation, and an Advisor at Gulf State Analytics (Washington, D.C.). He received his PhD in Contemporary Political and Social History from the Autonomous University of Barcelona. His areas of interest include Kaliningrad and the Baltic Sea region, Russian information and cyber security, A2/AD and its interpretation in Russia, the Arctic region, and the development of Russian private military companies since the outbreak of the Syrian Civil War. He has consulted or briefed with CSIS (Canada), DIA (USA), and the European Parliament. He is based in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

No comments:

Post a Comment