China has tried to take advantage of the Coronavirus crisis to boost its international role and status. Nonetheless, China’s own mistakes in battling the virus as well as diplomatic aggressiveness have raised doubts about its capacity to become a world leader.

Originated from Wuhan, the current Coronavirus pandemic, known as COVID-19, is a good illustration of how the Chinese government has tried to grasp an unprecedented health crisis not only to demonstrate its capacity to rapidly overcome it but also to enhance its diplomatic influence, improve its international image and challenge the US dominant status both as a leading health care provider and a world role model. Has China succeeded? Taking advantage of its close relationship with the World Health Organization (WHO), the Trump Administration’s late mobilization against this novel coronavirus, the European Union (EU)’s disorganization and divisions, as well as each country’s preoccupation with its own domestic health crisis, China has achieved early successes on the international stage, particularly in Eastern and Southern Europe as well as in the Global South. Nonetheless, the Chinese government’s initial failure in the management of the health crisis at home as well as the aggressiveness and incoherence of its own narrative have contributed to denting the credibility of its own data and its “politics of generosity”.

The COVID-19 crisis has also highlighted how much the world had become dependent upon China’s medical and pharmaceutical products, leading in particular the US and its allies, if not to fully decouple, at least to reduce their dependence upon this country. More generally, rather than mitigating the economic and geostrategic competition between China and the United States, this unprecedented planet-wide health crisis has intensified the “new Cold War” between the two great powers. While it has hurt the US’s prestige, it is far from having demonstrated China’s ability to lead.

As it is now well-known, in Chinese the word crisis (weiji) is made of two characters, danger (wei) and opportunity (ji). The current Coronavirus epidemic is a good illustration of how the Chinese government has grasped an unprecedented health crisis at home not only to demonstrate its medical, administrative and political capacity to contain and later overcome it but also, as COVID-19 was turning into a pandemic, to enhance its diplomatic influence, improve its international image and challenge the US dominant status both as a leading health care provider and a world role model. Taking advantage of its close relationship with the World Health Organization (WHO), the Trump Administration’s late mobilization against this novel Coronavirus, the European Union (EU)’s disorganization and divisions, as well as each country’s preoccupation with its own domestic health crisis, China has achieved early successes on the international stage, particularly in Eastern and Southern Europe and in the Global South. Nonetheless, as we will see, its “politics of generosity” has already backfired.

In the shorter-term future, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) will need to focus on the challenges it is facing at home, contain COVID-19 second wave, resume economic activities, and reassure the society about its initial failures in the management of the health crisis. China will also have to face and handle a relationship with the US and its allies both in Europe and Asia which have become much more delicate because of the aggressiveness and incoherence of its own narrative, not only about the pandemic but also Western countries’ political system and the world order.

Chinese experts including Zhong Nanshan (middle) denying any evidence that Wuhan was the source of the Coronavirus spread (Getty)

Chinese experts including Zhong Nanshan (middle) denying any evidence that Wuhan was the source of the Coronavirus spread (Getty)

In other words, it is necessary to look at the CCP’s battle against the Coronavirus in the context of a deepening economic and geostrategic competition and, I would argue, a “new Cold War” between the US and China. Of course, in one important respect this new Cold War is different from the old one between the West and the now-defunct Soviet Union: China is part of the world economy and the level of economic, social and human interdependence between this country and the rest of the world is much higher than the USSR’s. However, globalization has not prevented a growing economic, geostrategic and ideological rivalry between China and the US from taking shape. On the contrary, helping China to get stronger and to claim America’s status, globalization has contributed to intensifying this rivalry and creating a new bipolarity in world politics.(1) And this planet-wide health crisis has highlighted how much the world had become dependent upon China, and not only in terms of medical and pharmaceutical products, leading in particular the US and its allies to attempt to reduce this dependence. While trying to keep a non-conflictual and predictable working relationship with Beijing, US allies both in Asia, particularly Japan, South Korea and Australia, and Europe (NATO members) cannot ignore this new bipolar geostrategic environment. And as we will see, the growing efforts of the EU and the US not only to manage the pandemic at home but also to help poorer nations to defeat it are likely to partly offset the diplomatic benefit that China can draw from it.

Possible Geopolitical Gains

COVID-19 originated from Wuhan, possibly as the result of a mutation between infected wild animals sold in this municipality’s wet market and humans. The first human case appeared in mid-November 2019 but it is only on December 31 that the Chinese government informed the WHO about the existence of “cases of pneumonia of unknown etiology (unknown cause) detected in Wuhan”.(2) But it was only on January 20, 2020 that Chinese health authorities reported to the WHO that this virus was transmittable among humans. The same day, the Chinese President Xi Jinping declared a national mobilization against this new epidemic and three days later a lockdown was imposed on Wuhan and the whole province of Hubei.

We now know that some Chinese medical doctors, as Li Wenliang, had alerted the public about the dangers of this new zoonotic virus but were then silenced and reprimanded. We also know that many medical staff complained about the lack of masks and other personal protective equipment (PPE), and that segments of the society criticized the government for its censorship of the whistle-blowers and its late mobilization against the virus. But the Chinese authorities have been able to swiftly mend their image in addressing some of the domestic complains and in propagating a powerful international narrative aimed at demonstrating their political system’s capacity to rapidly contain and overcome the COVID-19 epidemic and this, better than and ahead of the rest of the world.

Whistleblower Doctor Li Wenliang dies of Coronavirus after he was punished for spreading 'false rumors" by Chinese authorities (Getty)

On the one hand, domestically, in mid-February, Xi sacked Hubei and Wuhan’s key officials and replaced them with some of his protégés. To calm down the public’s emotion, he also swiftly decided to launch an investigation on the Li Wenliang case and rehabilitated him postmortem (Li died of the virus in early February). On March 10, he eventually visited Wuhan and, turning his back to the suggestions made by local officials, instead of asking the local people to show gratitude to the Party and his leadership, he declared them “heroes”. These decisions have helped Xi pass the COVID-19 “stress test” and, as China was getting out of a crisis that had propagated overseas, if not consolidate, at least stabilize his power.(3) On the other hand, the Chinese government has launched an unprecedented international campaign, asking its diplomats to pro-actively highlight the superiority of China’s one-party system over “Western” democracies, and even convince the authorities and elites of the country in which they are located to praise China for its management of the crisis. It has also tried hard to present itself as a model pupil of the WHO, underscoring the fact that it had informed it without delay about the epidemic at home (in contrast with its resistance to do so at the time of the SARS crisis in 2003), and more generally as a role model in terms of cooperation with the United Nations, international state-based organizations and multilateralism.

More generally, since early March, the Chinese diplomacy has been entirely geared to serve the fight against COVID-19 and demonstrate China’s solidarity with the whole world as well as leading role in this fight. When in early March 2020 COVID-19 became a pandemic, China promoted itself as an experienced “elder brother” helping other countries to understand the virus and rapidly providing them masks and other PPE. China’s assistance to Italy, the first EU member-state to be badly-hit by the virus, has probably been the most spectacular one for the “Global North” as a whole. While Germany and France, for national security reasons, were blocking export of masks and other medical materials to Italy, China sent an experienced medical team and delivered large quantity of equipment to this country.(4) More importantly, it gave much publicity to this assistance, both in its own national media and on its diplomats’ twitter accounts. As a result, while Germany and France’s initial behavior was harshly criticized by Italy, this country’s media praised China, a gratitude that was largely capitalized upon by the CCP propaganda.(5)

Other EU countries as Spain(6) and Hungary(7), and EU candidate member-states as Serbia have also benefited from China’s “face mask diplomacy”(8), denouncing EU’s lack of reactivity and solidarity. To the point that Serbia bluntly declared that China was more helpful than the EU in its fight against the virus. In the same spirit, in early April 2020, Hungary signed a US$2.3 billion railways construction contract with China which will remain secret for 10 years, voluntarily turning its back to EU transparency recommendations. In Central and Eastern Europe, the virus has itself become a fresh “vector” for China’s influence.(9) More generally, China’s timely assistance has contributed not only to dividing the EU along already existing fault lines – the member-states most critical towards the EU are the ones which have joined China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – but to highlighting the EU’s unpreparedness and disorganization.

A 14th-century painting showing the caravan of Niccolò and Maffeo Polo crossing Asia (Getty)

A 14th-century painting showing the caravan of Niccolò and Maffeo Polo crossing Asia (Getty)

But it is probably in the Global South that China’s helping hand in the fight against COVID-19 has been the most visible. China is not the only country active there: among its friends, Russia and Cuba have also provided medical assistance. But China’s aid has been the best publicized. Every delivery of Chinese package of assistance was dutifully reported by Chinese and local media, underscoring the close relationship Beijing has developed with many developing countries. In Africa, where it is already very influential economically, diplomatically and politically, China has provided medical equipment to a large number of countries, for example Algeria, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Senegal, South Africa and Zimbabwe. Taking advantage of its privileged links with Ethiopia, the Chinese government has also promoted the role of Addis Ababa, the seat of the African Union and Africa Center for Disease Control and Protection (CDC) of which it is currently building the headquarters with an $80 million donation, as a hub for distributing assistance. The quantity of equipment delivered has been far from impressive (ex: one million masks to Ethiopia) but this assistance has been accompanied by an inclusive narrative that has revealed itself very efficient. As a result of this charm offensive, most African countries have publicly praised China.(10)

While the role of Chinese foundations and companies in disaster relief operations taking place overseas is not new, it is the first time that Beijing has promoted with such publicity their contribution, clearly with the objective of giving a more open and amicable image of China. This has been in particular the case of Jack Ma’s Alibaba Foundation which has generously distributed large quantities of free masks around the world including in the USA. This has also been the case of Huawei which has been very active providing medical equipment, particularly in Africa, where it already enjoys a dominant position in the telecom sector, but also in Canada, with the hope to mollify this country’s government in the extradition case of Huawei founder’s daughter, Meng Wanzhou.(11)

The Trump administration’s slow reaction to the COVID-19 crisis, and expansion of the pandemic within the United States have given China a golden opportunity both to mitigate the growing tensions between the two countries but also to appear as the real leader in this battle. Rapidly, because of the US’ lack of preparedness, Beijing was able to appear as the only or the main medical equipment provider to this country, putting pressure on the Trump administration to accept imports of masks and PPE from China, and reviving a probably unwelcomed (by Trump) debate about US’s China policy, as well as the benefits of a globalization that includes China. Since COVID-19 hit the US, Chinese officials have been very effective at developing this line of thinking and reasoning.(12) In April, the need to lift restriction on American company 3M-manufactured masks import from China has forced the US political and economic elite to face its contradictions and opt for the fruits of globalization against the trade war weapons deployed by Trump.(13)

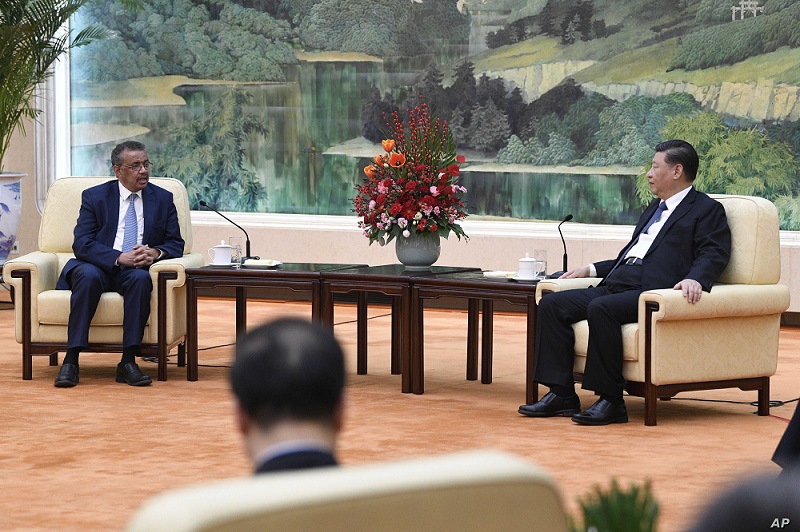

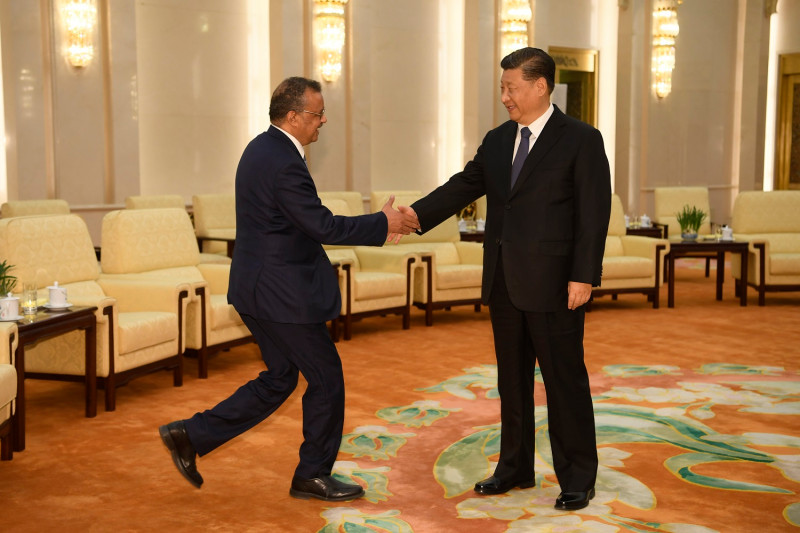

President X meeting with WHO General Director in Beijing (Getty)

President X meeting with WHO General Director in Beijing (Getty)

But more globally, Trump’s US lack of international leadership and solidarity, and the EU’s slow motion and disunity have opened to China a boulevard which it has been quick to use, promoting its role as the world’s doctor and, to some extent, the world’s new leader.(14) Are these achievements genuine? Can they have a long-term impact on the balance of power between China and the US as well as between authoritarianism and democracy. Can they convince more countries to befriend with and move closer to China to the detriment of the US and the West? Actually, these gains may have been superficial since as this health crisis is still unfolding China has already been facing real challenges.

Real Challenges

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic, the CCP leadership has been facing multiple domestic and international challenges, including in the Global South, that question the efficiency of its strategy.

1. Domestic Challenges

While after mobilization was decided the Coronavirus was rapidly contained thanks to strict confinement measure and a complete lockdown of Hubei province, the Chinese government was compelled to address the double pressure from the medical community and the public for more accountability and transparency. Actually, in early February 2020, the CCP leadership, and especially President Xi, faced a genuine “crisis of governance”.(15) Local authorities had hidden the truth about the virus from both the central government and the WHO. In spite of censorship, Chinese social media were overflown with messages criticizing the government and asking it for more transparency. President Xi Jinping was especially singled out for not having led the battle against the virus himself and earlier. Chinese internet users have also raised doubts about official statistics regarding the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths, suggesting that the total numbers should be around three times higher than the governmental reports indicated. Adding to these doubts, the authorities recognized that they had left asymptomatic cases outside of the data,(16) deciding only in late March to include them.(17) Nonetheless, this decision has not put an end to the controversy, owing to the logistical difficulties to conduct tests, and because more than two third of the new cases have no symptoms.(18) Outside of China, some analysts estimate the number of cases to 2.9 million instead of around 83,000.(19)

Workers setting up beds at the Wuhan Parlor Convention Center to convert it into a makeshift hospital February 4 2020 (Reuters)

Workers setting up beds at the Wuhan Parlor Convention Center to convert it into a makeshift hospital February 4 2020 (Reuters)

In the same period of time, several civil society actors, as Tsinghua University Professor Xu Zhangrun, private entrepreneur Ren Zhiqiang and political activist Xu Zhiyong, started to publicly denounce the “crisis of governance” provoked by CCP opaqueness and censorship as well as Xi’s power concentration. While they were rapidly silenced – in addition Ren disappeared and was put under investigation, Xu Zhiyong was arrested – , more critical voices could be heard on China’s social media, before most of them were taken down.(20) In other words, some segments of the civil society, and also perhaps of the CCP leadership(21), have taken advantage of this health crisis to try to weaken President Xi and question the decision he made in early 2018 to stay more than the usual ten years in power.

Although Xi has apparently managed to overcome for the time being these attacks, the CCP regime is facing another and probably more serious challenge: the slow and uneven recovery of the economy in an international environment that is much less favorable than before. While since mid-March the Chinese government has been keen to resume production and encourage most workers and employees to go back to work as fast as possible, it is facing numerous obstacles. Domestically, many provinces, as Jiangxi, Guangdong and Zhejiang, and municipalities, as Beijing, continue to put restrictions on migrant workers willing to travel back from Hubei to their working place. While production has officially reached in early April 90% of its pre-crisis level, consumption is still sluggish. Fearing a second wave of (imported) Coronavirus, social distancing remains a rule, negatively affecting the service sector. Moreover, because of a high level of internal debt (around 300% of GDP), the government’s stimulus package has been so far rather modest ($350 billion) compared to the ones announced by the US ($2.2 trillion), Japan ($992 billion) or the EU ($600 billion), and concentrated on lending to business and encouraging consumption.(22) Since China has remained highly dependent upon its exports (19.5% of its GDP in 2018), it will continue to suffer a drastic reduction of its exports to all the countries affected by the pandemic.

This will directly impact migrant workers and the segments of the society, particularly in rural areas, that have been left behind. In total, it has been estimated that while urban unemployment has already jumped in February to 6.2% from 5.2% in December 2019 (5 million jobs), the Chinese economy is likely to lose 24 million jobs as a result of the current crisis and grow only by around 2.5% in 2020.(23) Although economists remain divided, it is fair to forecast that China will play a weaker role in the recovery of the world economy.(24) A final unknown is the extent of the epidemic within the PLA. Officially, not a single soldier has been contaminated. In reality, as North Korea, the Chinese military are keen to keep any figure on this matter a state secret.(25)

Chinese president XI assesses the victory against the spread of coronavirus (Reuters)

Chinese president XI assesses the victory against the spread of coronavirus (Reuters)

2. International Challenges

As we have seen, China has clearly tried to take advantage of the pandemic to appear as the new world leader. A world leader, that contrary to Trump’s America, is able to reach out every nation politically and in terms of emergency assistance as well as to promote multilateralism, with the UN system and the WHO at its heart. However, China’ – and Xi Jinping’s – international ambitions have faced two major challenges: more nations have become wary of Beijing’s generosity and global ambitions; far from persuading the US to cooperate with China in its battle against the Coronavirus, the current health crisis has persuaded both the Republicans and the Democrats to confront more squarely this country.

This growing wariness is the result of Beijing’s massive propaganda campaign and rather clumsy communication strategy. The CCP wanted to demonstrate too many things in the same message: first, that it had better managed the epidemic at home thanks to its one-party system and Xi’s personal role; second, that it was ready to help all the other countries facing the pandemic in a very disinterested manner; third, that was not responsible of the migration of the virus around the world; and fourth, that it had some doubts about the origin of the disease, maybe coming not from China but the US military or even Italy.(26)

In other words, China’s “public opinion warfare” has rapidly appeared at the same time too aggressive and rather incoherent. As a result, it has badly backfired. Part of the CCP’s “three warfares” (with psychological and legal ones), this strategy has highlighted one of the most persistent but also darkest features of China’s communication strategy, conceived as a war against enemy forces that need to be defeated.(27) This binary approach to messaging actually underscores the lack of self-confidence of a regime that sees itself as a besieged fortress. In such circumstances, how can the CCP narrative reach out and convince the international community? The CCP propaganda’s overkill has actually contributed to both destroying the message and damaging the messenger’s credibility.(28)

Consequently, China’s ambition to teach Western democracies and the world a lesson by its own acts, and in particular its highly-publicized assistance, after an initial welcome, has fed criticism and anti-China sentiments in the West, and especially in the EU. Very quickly, China’ “mask diplomacy” irritated Brussels. For example, on March 24, 2020, EU High Representative Josep Borrell criticized the “battle of narratives” in which China had engaged as well as its “politics of generosity”.(29) The EU Commission was particularly upset by the Chinese government’s double standards: in January, it had reportedly asked the EU to “keep it quiet” about its assistance to Hubei and two months later, it noisily boasted about its own aid to worst-hit European nations. Moreover, China gave the impression of being very generous while it often conflating aid with sales; the equipment it sold was expensive and often defective.(30) That was particularly the case of its test kits declared faulty by several countries all the way from Sweden to the Netherlands and the UK, from Spain to Italy. But also of its surgical masks (Austria, Canada, Finland), compelling Chinese Customs to introduce inspections of these export products.

Even Italy’s divided political elite had mixed feelings about China’s assistance. The Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Luigi Di Maio, actively welcomed Beijing’s new “health Silk Road” because he was the architect of Italy’s BRI MOU, favors Huawei for his country’s 5G and his party, the Five Star Movement (FSM), is openly pro-China. But other members of the government have kept their distance from this country.(31)

China sends medical experts and hospital equipment to help in Italy's Coronavirus emergency March 12 (Reuters)

China sends medical experts and hospital equipment to help in Italy's Coronavirus emergency March 12 (Reuters)

Actually, if China did not publicize much the substantial help that it received from the EU and the US in the early stage of the epidemic, it is because it is engaged in an overall political and ideological confrontation with the West and what it calls “Western democracy”.(32) More generally, in promoting Xi’s “Beijing Model”, China has ambitioned to “exhibit a leadership role in global affairs, but without a corresponding sense of responsibility and accountability”.(33) It has also intensified the rivalry between “China Inc.” and “America First”, feeding the emerging Cold War between the two great powers.(34)

To be sure, Sino-US relations were already bad before COVID-19. But China’s management of the epidemic, its ignorance of the US offer to help and later its official speculations in March that the virus may have been brought by US military taking part in the Wuhan games in October 2019 triggered an eruption of anti-China sentiments in the US that Donald Trump stirred up when he called the pandemic the “Chinese virus”. In spite of their call for cooperation with Beijing, Trump’s opponents could not really capitalize upon the US President’s late awareness of and erratic reaction to the pandemic. The fact that this call was published right after 100 Chinese academics had signed an open letter denouncing the “politicization” of the COVID-19 pandemic” and making a similar proposal did not help.(35) In any event, Xi and Trump spoke on March 27 and accepted to cooperate, but the content of this cooperation has remained undefined. And after the war of words was over, very few Americans among the political elite as well as the public have expressed any trust in the way China had managed and informed the world about the epidemic. Moreover, a large majority of them think that China is responsible of the pandemic and, more importantly, US manufacturers should pull back from this country. As a result, in the post COVID-19 context, pro-engagement policy with China has even less market in the US.(36) In other words, Beijing’s more conciliatory tactics adopted in late March and Jack Ma’s donations have been unable to reverse the trend.

On the contrary, underscoring US economy’s high level of dependency upon China, especially for the products needed to fight the virus (surgical masks, PPE)(37), the pandemic has given additional arguments to Trump and his closest advisors as Peter Navarro to push further for economic decoupling with China, and perhaps question globalization the way it was understood and encouraged before this crisis.(38) COVID-19 has also revealed how much China has been able to enhance in the last two decades or so its influence in the state-based multilateral organization, particularly in the UN system and the WHO. While Beijing may consider this influence as a deserved achievement, it has triggered many negative reactions not only in the US and Europe but in a large number of countries, including in Asia, for instance in India.(39)

China sent to Italy a team of nine Chinese medical staff along with some 30 tons of equipment on a flight organized by the Chinese Red Cross March 12 (Getty)

China sent to Italy a team of nine Chinese medical staff along with some 30 tons of equipment on a flight organized by the Chinese Red Cross March 12 (Getty)

WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom has been particularly criticized for having uncritically repeated information provided by the Chinese government, initially opposed any restriction to air traffic to and from China and delayed the decision to declare COVID-19 both a “public health emergency of international concern” (until January 30) and a “pandemic” (until March 11), not to mention his constant ostracism of Taiwan, which is not a UN member because of China’s opposition.(40) In other words, for many around the world, the WHO also bears some responsibilities in the spread of this epidemic. While President Trump’s threat made in mid-April to stop funding the WHO may be temporary, the WHO’s pro-China bias is likely to put this organization under closer scrutiny in the coming years.

Actually, the COVID-19 crisis has given Taiwan a window of opportunity to remind the world that it should be part of the WHO, in spite of China’s objections which claims the island as part of its territory. The US(41) but also the EU(42), some European countries as the Czech Republic and Japan have openly thanked Taiwan for its surgical masks donations, expressions of gratitude that Beijing has heavily criticized. In order to mitigate this evolution, the Chinese government has tried to maintain proper communication with Taipei.(43) But its constant military pressures on the island-state show that it is not ready to make any concession to Taiwan’s independence-leaning authorities.

Finally, US’s Asian allies as Japan and South Korea, have rapidly closed their borders and adopted their own methods to mitigate the virus’s progression. Although these countries’ government has been cautious not to antagonize too much China, their society and elites have been much more critical.(44) Consequently, it is likely that they will use this pandemic as an excuse to take more decisively their distances from China.

3. Impact on China’s Relations with the Global South

COVID-19 will probably have also a negative impact on China’s relations with the Global South.

It is true that China’s closest neighbors, especially in Southeast Asia, have by and large remained loyal to it, uncritically accepting its narrative.(45) But the pandemic has also exposed “the risks and weaknesses of global interconnectedness”.(46) As a result it is going to negatively affect China’s BRI. Because more resources will be need at home, China’s BRI is likely to become less ambitious, putting on hold or slowing down infrastructure projects in Asia or in Africa that, on their side, recipient countries as well are less able to finance. The Global South, and particularly Africa, have already asked the G20 for debt relief. In April, the Chinese government has indicated its readiness to temporarily freeze debt payments and negotiate debt rescheduling bilaterally with its most exposed partners and multilaterally with the G20. But, as in the past, it is unlikely to grant more than symbolic debt forgiveness. In any event, while in Beijing’s view, the impact of the pandemic on the BRI will only be temporary, we can raise some doubt about this optimism.

WHO chief meets with Chinese president (Getty)

WHO chief meets with Chinese president (Getty)

Even in Africa where China has been very active, its image has deteriorated because its message has been far from being clear. Sometimes aggressive, promoting its political model as alternative to Western democracy, sometimes inclusive and ready to cooperate with the West, the Chinese propaganda has actually exacerbated its ideological rivalry with the West in Africa and contributed to dividing rather than uniting the Africans.(47) Moreover, since COVID-19 outbreak, Africans living in China have accused the local authorities and society of discrimination and even racism, triggering for the first time a large mobilization of African governments and diplomats against the way their nationals are treated in China. These incidents will have a lasting negative impact on Sino-African relations.

Conclusion: Post-America Age?

In spite of the risks of a second wave, China is getting out of the COVID-19 pandemic ahead of the rest of the world. Nonetheless, its international image and its relationship with its major partners have on the whole deteriorated rather than improved because of this crisis, deepening the emerging Cold War with the US and raising more questions about its ability to play a leading role in global affairs.

It is true that, through this unprecedented health crisis, the Chinese government has been able to demonstrate its ability to reach out many countries and many parts of the world. It has also shown its readiness to work with the international community, bilaterally as well as multilaterally, via in particular the WHO and the G20.

However, both for domestic and foreign policy reasons, China has overplayed its hand. Xi needed to counter the offensive that some in the country and the CCP itself had launched against him. And he also felt that it was the right moment for his country to assert its global clout. While Xi has for the time-being managed to stabilize its powerbase within the Party, his international activism has badly backfired because of its aggressiveness and lack of clarity.

It is also true that the Chinese government has been able to use the pandemic to consolidate its relations with some of its partners. But most of them, from Hungary to Serbia in Central Europe to Thailand and Cambodia in Asia, already entertained close partnerships with China before COVID-19.(48) And with some of its de facto allies, as Russia, which very early on closed its borders with China, or Iran, which accused China of being the origin of the epidemic on its soil, relations have on the contrary become more complicated.(49)

It is unlikely that the various initiatives that have been taken in the United States or even in India to make China legally responsible of the pandemic will ever succeed.(50) Nonetheless, they are indicative of a changing mood both in the North and the South about the world’s second superpower. They inform us how suspicious of China, especially the CCP opaqueness and the credibility of its data, the international public opinion has become. They are also the manifestation of a growing Sino-American bipolarity and Cold War. In other words, rather than mitigating this deepening bipolarity and Cold War environment, the COVID-19 crisis has actually intensified it, compelling China to face more squarely in the future the two major challenges that it is facing: namely, an accelerated de-globalization and a growing contestation of its ability to replace the US as the great power that sets the international norms and acts as a role model.

Health measure in Hong Kong (Reuters)

Health measure in Hong Kong (Reuters)

One of the most direct consequences of the current pandemic is likely to be a reassessment in many countries of their dependence upon China and not only in terms of medical equipment and pharmaceutical products, and affect their supply chains.(51) More generally, COVID-19 has already revived the debate about decoupling in the US and strengthened the arguments made by the politicians, particularly in Europe and the Global North, favoring de-globalization. Although a full Sino-American economic decoupling is not only unlikely but also impossible, in sensitive sectors, as high-tech, it will probably speed up. Moreover, the pandemic has clearly highlighted the risks attached to one-sided dependence and intense connectivity.

COVID-19, to be sure, has challenged the US’s ability to lead and show the way. The Trump Administration is largely responsible of this lack of leadership. But, as often in the past, the US is likely to eventually make the right moves, stimulating its economy and competing with China and others to provide the Global South the assistance that it needs.(52) In spite of their frictions with the Trump Administration, the EU and the major European member-states will also play a part in this effort, reducing the diplomatic benefit that China can draw from this health crisis. For example, the EU has already pledged $15 billion to Africa and other developing countries.

Some have argued that the Coronavirus marks the first crisis of the Post-America age. Actually, this crisis has rather shown how much the world lacks leadership and is rapidly moving towards G0 rather than G2 or even multipolarity.(53) As the same time, while humiliated, the US is likely to continue to play a leading role in the world, because not only of its sheer economic weight and dynamism but also its numerous alliance systems and, in spite of Trump, its soft power.(54) These power attributes will probably continue to offset China’s growing influence in the Global South and the UN system, particularly the WHO. Beijing claims that it is striving to build a “community with a shared future for mankind”. But COVID-19 has shown on the contrary that large parts of the world do not wish to share the same future as the Chinese communists.

No comments:

Post a Comment