By Umair Jamal

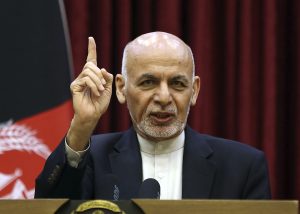

Last week, the Afghan Taliban refused to meet a negotiating team that included Afghan President Ashraf Ghani. The Taliban’s spokesman, Zabihullah Mujahid, in a statement said that “In order to reach a true and lasting peace, the aforementioned team must be agreed upon by all effective Afghan sides so that it can represent all sides.”

Last week, the Afghan Taliban refused to meet a negotiating team that included Afghan President Ashraf Ghani. The Taliban’s spokesman, Zabihullah Mujahid, in a statement said that “In order to reach a true and lasting peace, the aforementioned team must be agreed upon by all effective Afghan sides so that it can represent all sides.”

The Taliban’s position should not come as a surprise and doesn’t reflect a setback for the peace process if one is to consider the development in the conflict’s totality. If anything, the group is only doing what it should be expected to do: undermining the credibility of a political leader whose regime faces a crisis of legitimacy at home and from abroad.

It’s important to note that it’s not only the Taliban that has refused to meet Ghani’s negotiating team. Ghani’s political rival, Abdullah Abdullah, who also declared himself president after last September’s controversial election has not supported the team formed to negotiate with the Taliban. Other political leaders with significant clout in Afghan politics including Hamid Karzai, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, Abdul Rab Rasul Sayyaf, and Rahmatullah Nabil have not made their position clear. All of these political leaders have an interest in seeing a regime in Kabul that meets the Taliban with the complete support of Afghanistan’s political leadership. Amid a crisis between Abdullah Abdullah and Ashraf Ghani, it’s unlikely that any of these political leaders will support a team unilaterally formed by President Ghani.

Moreover, for Ghani’s part, the decision related to forming a negotiating team with the Taliban was done in haste. The development is nothing short of a gamble that may undermine the intra-Afghan peace process further. Ghani’s announcement to begin an intra-Afghan dialogue without making a deal with Abdullah only made a historic declaration insubstantial and crippled the legitimacy of a most important part of the peace process.

Ghani needed to go into talks with the Taliban with Abdullah and other members of the political class of Afghanistan flanking him. Perhaps only that could have made the Taliban interested in sitting across Afghanistan’s political leadership. The negotiations between the United States and the Taliban should have taught Ghani a clear lesson: Washington couldn’t get what it wanted from the Taliban even after it brought to the table the support of almost all stakeholders that have anything to do with Afghanistan’s politics. It’s inconceivable how Ghani could deal with the Taliban when his regime has failed to meet the necessary requisites dealing with the political legitimacy of his government.

The best time to start the intra-Afghan dialogue was right after the United States and Taliban signed the peace deal. The narrative around the process’s legitimacy was the strongest a month ago. Afghanistan’s political leadership has wasted a valuable month and Ghani’s decision to go alone to negotiate with the Taliban may have turned Washington’s two years’ efforts into waste. Will the United States support Ghani’s unilateral move when the latter refused to come to an agreement with various other political rivals? Supporting Ghani would mean shredding efforts to build political consensus in Afghanistan. More than that, that would mean ignoring a leader whose camp has a strong influence in the country’s north and west.

Arguably, this is exactly the response one could have expected from the Taliban. The group was not going to offer Ghani the legitimacy he lacks by sitting across his team of loyalists. The Taliban understand that a consensus among the Afghan political elite would mean agreeing to a power-sharing formula that Ghani is unwilling or perhaps incapable of doing. Why sit across a political leader who may be on his way out from Afghanistan’s politics? The group just made Ghani’s job more difficult and gained points for demanding a panel that comprises of all political stakeholders from Afghanistan.

For its part, Washington is not going to condemn the Taliban’s position to reject Ghani’s offer. Consider this: Ghani and Abdullah have failed to agree on the power-sharing formula even after the United States threatened to cut $1 billion in aid and termed the leadership failure “a direct threat to U.S. national interests.” For many in the United States, it’s clear that Ghani’s attempt is a failure in the making and the Taliban’s refusal doesn’t harm it any further. If anything, Taliban’s refusal conveys that Ghani needs to go back to basics that involve doing what Washington wants and successfully negotiating with his political rivals.

Furthermore, the aid cut that Washington has threatened Afghanistan due to Ghani’s gambles is not something with the Taliban want as well. “We are ready to work based on mutual respect with our international partners on long-term peace-building and reconstruction. After the United States withdraws its troops, it can play a constructive role in the postwar development and reconstruction of Afghanistan,” wrote Sirajuddin Haqqani, the deputy leader of the Taliban. The group has already gained political legitimacy and going forward, what they need is the support of international donors as Haqqani’s article notes. Ghani’s attempt to sideline his political rivals and force Washington into issuing threats that involve cutting Afghanistan’s aid is not something that the Taliban may necessarily would like to happen.

Ghani has not only calculated wrongly when it comes to approaching intra-Afghan dialogue, but also shown his willingness to undermine other key stakeholders involved in the process. The intra-Afghan dialogue couldn’t have had a worse start.

No comments:

Post a Comment