By SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR.

The Future Combat Systems artillery vehicle in testing. FCS was cancelled in 2009.

WASHINGTON: “The Army learned nothing from FCS,” one industry official told me in January, after the service cancelled its third attempt in two decades to replace the Reagan-era M2 Bradley troop carrier.

WASHINGTON: “The Army learned nothing from FCS,” one industry official told me in January, after the service cancelled its third attempt in two decades to replace the Reagan-era M2 Bradley troop carrier.

But just weeks later, the service outlined out a new plan for the Bradley replacement program. Unlike the infamous Future Combat System cancelled in 2009, the short-lived Ground Fighting Vehicle cancelled in 2014, or the initial Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle competition cancelled this past January, the revised approach to OMFV has no rigid, government-specified technical requirements. The focus, instead, is on nine broadly defined “characteristics” and a new-found humility about asking industry for advice on how to achieve them.

This time, the same official told me, “they finally get it.”

The M2 Bradley has been repeatedly upgraded since its introduction, but after 40 years in service, the vehicle is reaching its limits.

Last week, the Army released extensive new details on the still-evolving OMFV program. “It’s a big improvement over their previous attempt,” the official said told me. “It’s a great start, and I’m cautiously optimistic.”

As the program figures out a new set of requirements, the official warned, “what to watch for is the KPPs” – non-negotiable Key Performance Parameters – “and what is tradable. What’s hurt their programs in the past is 200 must-haves with no ability to optimize through trade-offs.”

“While there’s always going to be tension between schedule and requirements,” the industry official said, “I believe requirements will always be the reason an Army program will fail.”

Has the Army figured out how to fix this longstanding problem? OMFV is a crucial test case, not just for one program, but for the entire Army effort to overhaul its infamously dysfunctional acquisition bureaucracy.

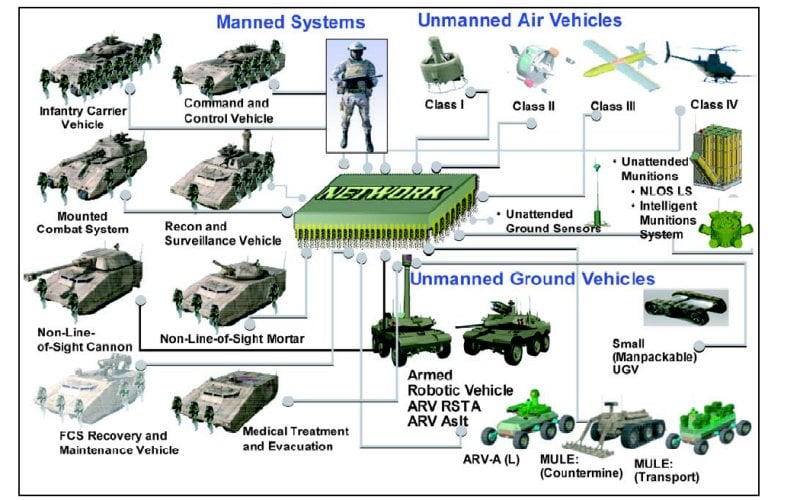

Army slide showing the elements of the (later canceled) Future Combat System

Greenwalt: ‘The Jury Is Still Out’

Some of the experts I interviewed for this article – all battle-scarred veterans of past acquisition disasters – shared the industry official’s guarded optimism. Others did not.

“I think the jury is still out as to whether the Army has learned anything,” former Hill and DoD staffer Bill Greenwalt told me after the initial OMFV competition was cancelled in January.

Last week, when the Army released details of the revised approach, Greenwalt grudgingly told me, “that outline makes more sense.”

Getting rid of the often-unrealistic technical requirements “could eliminate most of the unobtanium,” Greenwalt allowed. “They are at least doing market research by asking what industry thinks they could do. The problem is they should already know this from the last go-around.”

The other big problem? “I think they could go faster,” he said, “and they will run up against funding constraints if they don’t…as fiscal pressures intensify due to the trillions of dollars we are now spending that we don’t have.”

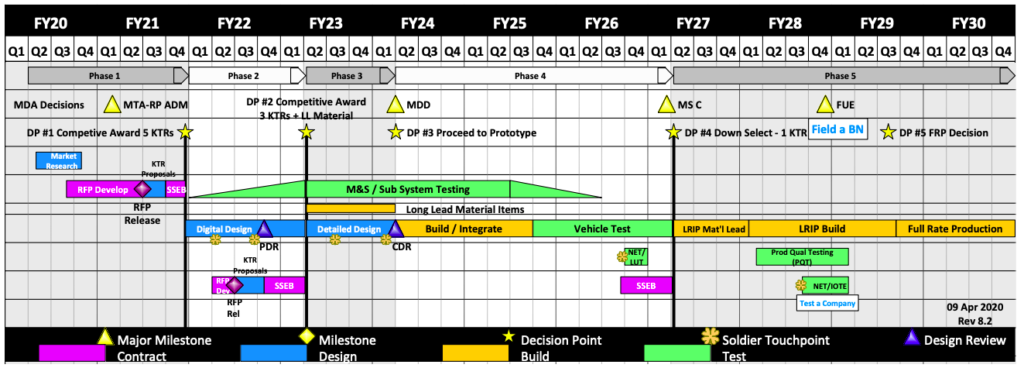

The revised schedule adds two years and multiple rounds of competition to the original plan. The original plan demanded bidders build prototypes at their own expense and deliver them to the Army last October. Just one company met that deadline, only to be disqualified anyway for not meeting the technical requirements. The new plan, by contrast, is to pay up to five vendors to develop “initial digital designs” from 2021 to 2023, then pick three to build competing physical prototypes by 2025, with one final winner receiving an initial production contact in 2027. The first combat battalion of OMFV should be ready in 2028, the Army’s target date to be fully prepared for war with Russia.

“Five digital designs is good, but a year-and-a-half to pick one to go to prototyping seems a long time,” Greenwalt told me. “Then, I know they said ‘up to three’ in the prototyping phase, but there’s the risk of the old Army reasserting itself and just doing one due to funding constraints. I think they do need at least three to prototype – but then 2.5 years to build them, and another year to test, seems excessive.”

“They don’t seem to be in a real hurry,” Greenwalt said. “I sense no urgency in this acquisition plan. They have to get over paralysis by analysis. Sometimes you just need to buy stuff, test it, and see if it works – and that may need to be done in larger quantities than current prototyping efforts.”

The Army’s latest, much revised timeline for the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle, released April 9.

Do Not Pass Go, Do Not Collect $200

Greenwalt wasn’t the only observer worried by the revised timeline.

“2028 is a long way away, so how do they keep this relevant in a rapidly changing technology world?” one industry expert asked me. “It looks like the old way of acquiring complex combat vehicles. Seven years before they get to the Milestone C [production] decision? By that time the technology they pick will be outdated, and the non-traditional defense companies don’t have the patience or the money to wait that long.”

“What has dismayed me about the Army’s approach, is that when they had a set-back, they didn’t just go back 10 spaces, they went all the way back to ‘Go,’ for a full reset,” said retired Lt. Gen. Thomas Spoehr, now head of national security programs at the Heritage Foundation. “So now they have a one to two-year delay at best, have lost hundreds of millions of dollars, and the program will face a much more challenging environment when it comes back to Congress for funding.”

Now, Spoehr never shared the skepticism about the initial approach that got cancelled back in January. “Maybe some of the requirements, like weight, were too aggressive, but most of it looked about right,” he told me. The bigger problem, he said, was “the program was accelerated to a speed where most of industry could not keep up – and my sense is that people were reluctant to take that message back to senior leaders.”

“Close involvement of Army leadership is one of the important qualities of their new modernization program,” Spoehr said – but that can backfire when subordinates are reluctant to admit such a high-visibility project is having problems.

Too much leadership investment is part of what sabotaged the Future Combat Systems. FCS was the brainchild of then-Chief of Staff Gen. Eric Shinseki, who pushed hard and fast for his very specific vision of the new vehicles, one that constrained their weight for ease of transport on Air Force cargo planes. Today, the four-star head of Army Futures Command and the service’s civilian acquisition chief closely monitor all 31 programs identified as Army priorities, and they report frequently to the Army secretary, undersecretary, chief of staff and the vice.

That said, “I continue to believe they have gotten the formula right with Army Futures Command,” Spoehr told me. “I believe OMFV is an aberration and not indicative of a larger problem.”

Raytheon Quick Kill Active Protection System in testing

New Process, Old Problems

Why is OMFV so hard? Because the basic technology of armored ground vehicles is not advancing anywhere near as rapidly as other areas. Compare the intense skepticism over OMFV with widely-praised programs for virtual-reality training, artificial intelligence, or even Future Vertical Lift aircraft.

Yes, sensors, jammers, and communications networks benefit from Moore’s Law. Computerized, radar-controlled Active Protection Systems can now shoot down some incoming anti-tank projectiles. But the only way to stop a high-velocity tank gun round remains heavy armor, and the only way to move a heavily armored vehicle long-distance remains a huge diesel engine.

“For decades, the Army has hoped for a technology either electronic or in materials science that would allow for more protection at lower weight. Now people are looking at active protection solutions as a potential solution to that problem,” Spoehr told me. “I am more pessimistic. Today, and I think for the next decade, the answer is mostly about steel.”

That argument got support from CSIS acquisition expert Andrew Hunter, a former Pentagon procurement official himself.

“The struggles of OMFV reflect the same challenge that the Army has faced for years with developing a next-generation infantry fighting vehicle,” Hunter told me. “The Army has sought a leap-ahead in technology that can deliver high levels of protection with tactically and strategically relevant mobility. This leap has not been forthcoming, and the tension between what the Army is seeking and what industry can deliver hasn’t been resolved.

“OMFV demonstrates the latest chapter in this story,” he said – but there’s a plot twist: The Army was able to admit the program was in trouble, cancel its first attempt, and start over with a new approach, rather than stubbornly pour good money after bad for years as it did on FCS.

The ongoing reboot suggests the reformed bureaucracy really has started learning from its mistakes, Hunter argues: “OMFV shows an ability by the Army to avoid some of its past errors.”

It’s better to avoid some errors than none. Will it be enough? We’ll have to watch how OMFV evolves.

No comments:

Post a Comment