BENJAMIN CHERRY-SMITH

Amidst the Covid-19 pandemic, domestic and international economies have been struggling. Markets have effectively been put on ‘pause’ in an effort to ‘flatten the curve’ of the continued spread of Covid-19. In function what this means is that people have been taken out of the economy – to varying degrees – through policies such as ‘social distancing’, ‘shelter in place,’ and limiting as much domestic and international travel as possible. While there are efforts underway to transition as many people as possible into working-from-home situations, these policies are intended to ensure that community spread of Covid-19 is reduced, while keeping as much of the economy running as possible. As a result of people are having their movements limited and travel restricted, they are travelling less. The flow-on effect on the global oil price has resulted in a depressed global demand for oil, resulting in a drop in prices.

Amidst the Covid-19 pandemic, domestic and international economies have been struggling. Markets have effectively been put on ‘pause’ in an effort to ‘flatten the curve’ of the continued spread of Covid-19. In function what this means is that people have been taken out of the economy – to varying degrees – through policies such as ‘social distancing’, ‘shelter in place,’ and limiting as much domestic and international travel as possible. While there are efforts underway to transition as many people as possible into working-from-home situations, these policies are intended to ensure that community spread of Covid-19 is reduced, while keeping as much of the economy running as possible. As a result of people are having their movements limited and travel restricted, they are travelling less. The flow-on effect on the global oil price has resulted in a depressed global demand for oil, resulting in a drop in prices.

The lowered demand has been a concern of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) since Covid-19 started to spread internationally, and China – their largest oil market, initiated lockdowns. Initially, this came to a head on the 4th of February, when OPEC held a meeting in Vienna to discuss how to address the lowered demand for oil from China. However, OPEC alone does not have complete hegemonic control over the global price of oil, only accounting for 55% of the oil produced globally. Instead, a fragile alliance between OPEC and Russia – known as OPEC+ – ensures that there is a globally consistent oil price. As OPEC sought to arrest the continued drop in demand for oil and ensure a stable and consistent price by lowering global production, tensions between OPEC and Russia began to rise as Russia was frustrated by both OPEC’s plan and the United States’ (US) lack of involvement.

Currently, OPEC has 13 member states, which together account for 55% of globally traded oil and an estimated 70% of the world’s oil reserves. OPEC aims to ensure a stable global oil market. Its leadership – officially a rotational presidency – is widely considered to be Saudi Arabia; a position that is evident when international negotiations are required on behalf of OPEC. OPEC often draws critiques, having been labelled a “cartel” as they use their global position to dominate the energy market by leveraging its global market share.

OPEC claims that it is an organisation that represents the interests of oil-producing states, but not all oil-producing states are members. Three notable non-member states are Canada, the US, and Russia. All three of these states are important actors in the global energy market, but the latter two states together produce 30% of the world’s oil. The reason behind why the US and Russia are not members of OPEC are complicated. For the US, the country’s geopolitical history, political tensions with existing OPEC members, and desire for energy independence have kept successive US administrations from joining the organisation. Russia’s reasoning for not being a member of OPEC is rooted less in its history, and more focused on its own international energy interests and desire not to have to conform to an international organisation’s will purely because it is a member.

While both the US and Russia are not OPEC members, both are heavily involved with OPEC. Importantly for current global oil price stability, OPEC+ is critical. OPEC+ came out of OPEC’s need to reinforce its global position of power within the international energy market, a position that was weakening. This alliance meant that Saudi Arabi and Russia would work closely together to ensure that global oil prices were consistent. This alliance worked because Saudi Arabi led OPEC policy and Russia is the world’s largest producer of oil. Together, they have the collective power to ensure that OPEC+ would be able to manipulate oil prices for their mutual benefit.

However, while Saudi Arabia and Russia can agree on fixing oil prices, their separate relationships with the US is a cause of political divide. US President Donald Trump has made no secret of his like for both Russian President Vladimir Putin and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. The difference between the two relationships is that while the US sells arms to Saudi Arabia, they sanction Russian oil producers.

The competing relationships between Washington, Moscow, and Riyadh has contributed to the breakdown between OPEC+ and the alliance’s ability to work together. In its February 4-6 meeting, OPEC+ tentatively agreed to a new production quota to ‘put a floor underneath the price of oil.’ This agreement would see production cut but 600,000-barrels-per-day. However, it is from this agreement where the current global oil price war was set into motion. While OPEC members had agreed on new production targets, Russia was hesitant to sign on to the deal to lower production. Moscow’s hesitation prompted Riyadh to engage in bilateral discussions. Cutting oil production is a common tactic employed by OPEC, as it entrenches a ‘seller’s market’ over a ‘buyer’s market.’ A seller’s market ensures that OPEC, and other oil-producing states, have market power dictating oil prices and are not just market players, competing for sales.

By the 5th of March, OPEC had met again to discuss a new round of production cuts as oil prices continued to fall. OPEC believed that a cut of 1,500,000-barrels-per-day would be enough to ensure market stability. However, Russia rebuked this move. Moscow felt that if OPEC+ kept lowering its oil production to ensure market stability, that same stability would only benefit the US’ oil industry as they did not need to meet production targets. The US’ oil industry has been frustrating Russia, as the industry had been growing unfettered by the influence of OPEC.

The March meeting proved to be the catalyst for starting the price war. Moscow, frustrated by continued US sanctions and prominent shale oil industry, did not agree with OPEC’s direction; it appeared a breakdown in the OPEC+ alliance was imminent. However, Moscow’s broader political ambitions and issues seemed too insurmountable to overcome which, as a result, led to the breakdown in the OPEC+ alliance. Riyadh reacted to this by increasing production and supply of oil, leading to the price war, with the desire to both punish Russia’s unwillingness to cooperate and to bring it back into the fold of OPEC’s influence.

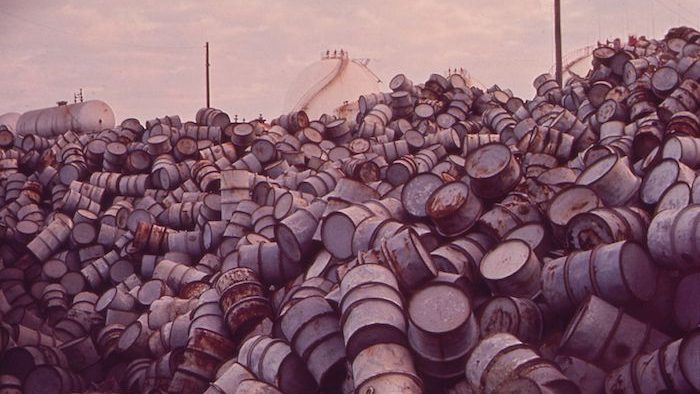

The problem of a price war as a tactic to compel a state to conform to a policy direction is that it is a blunt instrument. A price war cannot be targeted at a specific state’s oil export while leaving the initiating state’s own oil price immune from the same backlash. By increasing the supply and storage of your own oil in a bid to collapse the price of oil of a targeted state will collapse your own price. While OPEC’s international position requires it to work with non-member states in order to control global oil prices; however, it can work unilaterally collapse global oil prices.

There is no doubt that the US is an influential player with the potential to end the price war, either directly or indirectly. At the beginning of the price war, President Trump hailed it as ‘good for consumers,’ but as it dragged on the pressure on US oil companies was becoming apparent. Prompted by an oil industry under pressure and the political desire from Congressional Republicans, the Trump administration sought to bring Saudi Arabia and Russia together to agree to end the price war.

While the US could play a constructive role in mediating an end to the price war, it could also lean on its own oil industry and wield its political might to embargo oil imports from OPEC member states. US legislators have discussed this option with a bill, named ‘No Oil Producing and Exporting Countries Act of 2019’ (NOPEC), sitting in both the House and Senate which would make OPEC’s collective action illegal within the US. The likelihood of this bill becoming law is incredibly low. However, NOPEC’s purpose is not to become law, but to be another policy lever for the Trump administration to use in bringing an end to the oil price war.

Despite recent developments, the US has been unable to broker a longer term end to the price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia as the motives of the three states vary, making a timely end to the price war challenging to reach. Saudi Arabia is trying to ensure that OPEC remains not only relevant, but a powerful international organisation within the global energy sector. Russia is reacting to having US sanctions placed on its oil industry, and seeking to undermine the US’ oil industry, bringing the US into a quasi-QPEC+ relationship – where the US agrees to cuts its oil production. All the while, the US is trying to protect its oil industry and ensure a stable global oil price while coping with Covid-19. What is becoming apparent is that an oil price war is likely to continue in some form and the motives behind it are as much about addressing decreased global demand as it is an international power play between three oil-producing giants.

No comments:

Post a Comment