Thomas Graham

NEW YORK: Russian President Vladimir Putin refuses to yield under pressure. That is a matter of pride for Putin himself and a key aspect of his appeal to Russian elites and the public alike. The trick is preserving that reputation in the real world, where leaders routinely miscalculate and pivot while remaining loathe to admitting mistakes. The plunge in oil prices because of the COVID-19 pandemic and the collapse of the OPEC+ agreement on production cuts provide the most recent test.

NEW YORK: Russian President Vladimir Putin refuses to yield under pressure. That is a matter of pride for Putin himself and a key aspect of his appeal to Russian elites and the public alike. The trick is preserving that reputation in the real world, where leaders routinely miscalculate and pivot while remaining loathe to admitting mistakes. The plunge in oil prices because of the COVID-19 pandemic and the collapse of the OPEC+ agreement on production cuts provide the most recent test.

In early March, the Saudis called for a meeting of the OPEC+ group to agree on further drastic production cuts of 1.5 million barrels a day to support oil prices as COVID-19 spread, crushing economic activity and demand. The Russians balked. According to the spokesperson of Rosneft, Russia’s oil-sector national champion run by Igor Sechin, a close associate of Putin’s: “This deal made no sense from the standpoint of Russian interests. By removing cheap Arab and Russian oil from our own markets, we open up the way for expensive American shale oil.” Moscow wanted to maintain current levels of production for a few months to get a better sense of the economic consequences of the spreading pandemic before deciding on further cuts. And, when those cuts came, it wanted to make sure that the United States bore its fair share.

Moscow also had other reasons for wanting to strike a blow against the American energy sector. Late last year, Washington levied sanctions against Nord Stream 2, a strategic gas pipeline between Russia and Germany, pushing back its completion date by at least several months and raising costs, at a time when American shale gas was entering European markets. More recently, the United States sanctioned a Rosneft subsidiary, Rosneft Trading, for assisting the Maduro regime in circumventing US restrictions on Venezuelan oil exports.

But Moscow did not anticipate the Saudi reaction to its refusal to agree to further cuts. The Saudis’ threat to open the spigot and offer steep discounts on their oil exports pushed oil prices down to lows not seen in decades. The price war had begun, even if only the Saudis were prosecuting it robustly: The Saudis had the capacity to add 2.5 million barrels a day, the Russians, 300,000. True to form, Moscow was defiant. Despite Russia’s dependence on oil for two-thirds of its export earnings and 40 percent of its budget revenue, the Ministry of Finance announced that Russia could withstand prices as low as $25 a barrel for up to ten years. It would draw on its $150 billion National Wealth Fund to cover gaps in the budget, currently based on an oil price of $42 a barrel. That was certainly an exaggeration, and the Russian oil industry itself would suffer significant damage in the short term if wells had to be capped. Still, the ministry sent the unequivocal message that Moscow would not back down.

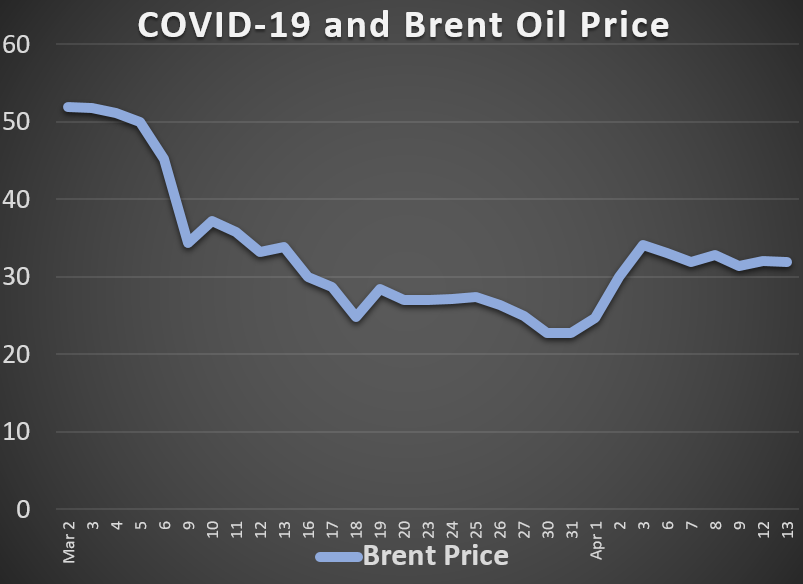

Downward slide: Many governments slow economic activity in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, yet an OPEC+ agreement to slash output may not lift prices to early March levels

Downward slide: Many governments slow economic activity in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, yet an OPEC+ agreement to slash output may not lift prices to early March levels

Despite such rhetoric, the collapse in oil prices raised grave domestic challenges for Putin. Earlier this year, in Russia’s analog to the State of the Union address, Putin stressed his determination to stimulate the economy and raise living standards, which have largely stagnated for the past six years. The bleak socioeconomic conditions were fueling discontent across the country, as Russians protested over educational, health and ecological matters, as well as official corruption, callousness and incompetence. The unrest has not risen to levels that threaten Putin, but the Kremlin has historically been wary of mass discontent – workers’ protests after all played a role in the overthrow of Russian autocracy in 1917 and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Now, the global economic consequences of COVID-19 would inevitably slow Russian economic growth. A prolonged collapse in oil prices would almost certainly push the economy into recession. Putin’s promises evaporated. In these circumstances, Putin needs to raise and stabilize oil prices. The question was how to do that without appearing to yield to Saudi or American pressure.

US President Donald. Trump gave Putin the opening he sought. Trump initially greeted the price collapse as a “big tax cut,” but by the end of March, he changed his tune under pressure from the domestic oil sector. He set about trying to persuade the two strongmen he had cultivated since assuming office, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and Putin, to agree to major production cuts.

On March 31, Trump called Putin to discuss the novel coronavirus crisis and oil markets. Kremlin statements routinely note who initiates the call when Putin talks to foreign leaders, and the Kremlin readout makes it clear that Trump made the call – the inference was that Trump, not Putin, urgently needed relief from the price war and the pandemic. The next day Russia sent a planeload of humanitarian assistance to New York, underscoring again that the United States, not Russia, was in need. Three days later, Putin announced that Russia was prepared to work with its partners, the United States and Saudi Arabia, to stabilize oil markets. Production, he said could be reduced by up to 10 million barrels day. He supported another meeting of OPEC+ to work out the details. As far as Moscow was concerned, cuts in US production, a key Russian goal from the outset of the crisis, would have to be part of the deal.

As Putin was pivoting, two narratives for the oil price war gained greater prominence in Russian media. One presented the Saudis as determined to drive American shale oil off the market by cratering oil prices. The other suggested the price war was, from the beginning, a US-Saudi conspiracy to undermine the Russian oil sector through a combination of production cuts and sanctions. The first narrative absolved Russia of any ill will against the United States, and the second portrayed Russia as an innocent victim. Both reinforced standard Kremlin tropes of Russian goodwill and victimhood.

Where oil prices will settle in the next few months is far from certain. Daniel Yergin, a leading expert on the global energy sector, has noted in Foreign Affairs that prices will likely plummet in late April and May as demand plunges and storage capacity is depleted. The cuts OPEC+ agreed to this weekend – 9.7 million barrels a day – are insufficient to stave off the decline in price. In this environment, US production will inevitably drop, as Moscow wants, but so will Saudi and Russian production, beyond what was already negotiated, if not through further negotiations then through market dynamics. No matter what Trump, MBS and Putin do, tougher times lie ahead. But, for Russians, despite the initial miscalculations, Putin will appear as a decisive and constructive leader in battling the crisis, playing a stronger hand than Trump. More important, Putin, and Russia, did not yield.

Thomas Graham, a distinguished fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, was the senior director for Russia on the National Security Council staff under President George W. Bush.

This article was published April 13, 2020.

No comments:

Post a Comment