John Calabrese

India’s interests and capabilities extend well beyond the subcontinent. This essay is part of a series that explores the geopolitical dimensions, economic ties, transnational networks, and other aspects of India's links with the Middle East (West Asia) -- a region that plays a vital role in India’s economy and its future. More ...

India’s interests and capabilities extend well beyond the subcontinent. This essay is part of a series that explores the geopolitical dimensions, economic ties, transnational networks, and other aspects of India's links with the Middle East (West Asia) -- a region that plays a vital role in India’s economy and its future. More ...

India is the largest country of origin of international migrants[1] as well as the world’s top recipient of remittances.[2] Since the 1970s “oil boom,” Indian migration to the Gulf has served as a valuable source of income for the nation and as the backbone of the economies of high-migration states such as Kerala through the transfer of remittances. During this time, Indian migrant workers[3] have made substantial contributions to the economic development of the Gulf States.[4]

However, the increasing international scrutiny and condemnation of the treatment of blue-collar and domestic expatriate workers in the region in recent years has cast India-Gulf migration in a far less favorable light, prompting greater attention by the Government of India (GoI) to diaspora affairs and worker welfare issues. Yet, complaints received from and on behalf of migrant workers regarding various forms of abuse, exploitation, and hardship persist.

Meanwhile, the outlow of Indian migrants to the region has slackened while return migration has increased due to economic slowdowns, fluctuating oil prices, and changes in Gulf labor policies. The future of India-Gulf migration is further clouded by the Coronavirus pandemic, which poses unprecedented health and livelihoods challenges for the millions of Indians working in the Gulf, as well as for the families and communities that depend on them — and which presents a daunting test for the Indian government.

The “Gulf Boom” – Fading?

The India-Gulf region is the second-largest migration corridor in the world. Of the nearly 31 million non-resident Indians (NRIs), an estimated 8.5 million are working in the Gulf.[5] [See Table 1.] Indians constitute over 30% of the expatriate workforce in the Gulf States, where the proportion of non-nationals in the employed population is among the highest in the world.[6]

Table 1. Population of Overseas Indians in the Gulf States, 2018

Country

Non-Resident Indians (NRIs)

Persons of Indian Origin (PIOs)

Overseas Indians

Bahrain

312,918

3,257

316,175

Kuwait

928,421

1,482

929,903

Oman

688,226

919

689,145

Qatar

691,539

500

692,039

Saudi Arabia

2,812,408

2,160

2,814,568

UAE

3,100,000

4,586

3,104,586

TOTAL

8,533512

12,904

8,546416

Source: GoI, Ministry of External Affairs, http://mea.gov.in/images/attach/NRIs-and-PIOs_1.pdf

Over the past decade, the pattern of Indian migration to the Gulf has changed noticeably. For one thing, the number of blue collar workers migrating to the Gulf States has decreased significantly.[7] This contraction is reflected in the sharp decline from its peak in 2014 in the number of Indians granted emigration clearances to work in the Gulf, as depicted in Table 2.[8]

Table 2. Number of Indian Workers e-Migrated[9] in 2019

Country

2015

2016*

2017

2018

2019**

5-Year Total

Saudi Arabia

306,000

162,000

73,000

66,000

143,000

750,000

UAE

225,000

159,000

141,000

103,000

42,000

670,000

Kuwait

67,000

70,000

51,000

52,000

72,000

245,000

Oman

85,000

61,000

4,900

32,000

26,000

209,000

Qatar

59,000

29,000

22,000

32,000

28,000

168,000

Bahrain

16,000

12,000

10,000

9,000

9,000

28,000

Malaysia

21,000

10,000

13,000

16,000

10,000

70,000

Others

85,000

15,000

2,000

2,000

4,000

108,000

Total

781,000

506,000

361,000

312,000

334,000

2,294,00

Note: * Figures for 2016 are to Dec. 15. ** Figures for 2019 are to Nov. 30.

The declining number of Indians departing for work in the Gulf stems from a variety of factors at both ends of the migration corridor.[10] The narrowing of wage differentials is one of them. Indeed, wage stagnation mainly due to sluggish oil prices has made the Gulf States less attractive destinations than in the past.[11] Another factor has been the implementation of programs to increase the employment of nationals in the private sector.[12] Nationalization policies have resulted in shrinking job opportunities for Indian migrants and those from other South Asian countries as well. Meanwhile, work permit renewal fees and taxes in the Gulf have increased, driving up the cost of living.[13] The cost of utilities and basic goods has likewise risen.[14]

The shrinking number of migrants heading to the Gulf is also partly attributable to the tightening of the procedures for sending workers abroad by the Indian government. In May 2015, the GoI introduced a computerized system called “e-Migrate” to regulate overseas employment. In recent years, the Indian government also set minimum referral wages (MRWs) to regulate the wages of Indian migrant workers employed in various capacities (e.g., as carpenters, masons, drivers, fitters, nurses, and domestic workers) in the six Gulf States as well as 12 other “emigration check required” (ECR) countries (i.e., those whose labor standards are identified as not migrant-friendly). Although both measures were instituted to safeguard the interests of those seeking contractual employment abroad, there is anecdotal evidence that they have had the perverse effect of making Indian workers less attractive for recruiters and employers.[15]

Paradoxically, remittances grew by over 14% in 2018 to $78.6 billion[16] despite the overall slowdown in Indian migration to the region. Several factors could account for the continuing healthy inflow of financial resources from the Gulf. The first is the sheer number of Indians who remain under contract and still remit a significant portion of their earnings. The second is the depreciation of the rupee.[17] The third is that some recently returned migrants have brought the wealth generated in the Gulf back to the country. The fourth is that, as data regarding Indian migrants from Kerala have shown, many migrant workers in the Gulf have ‘climbed the social ladder,’ garnering higher wages that have enabled them to remit larger sums.[18] And the fifth is that the Indian expatriate population in the Gulf includes a sizeable number of high-income earners whose remittances are not captured by the official migration data.

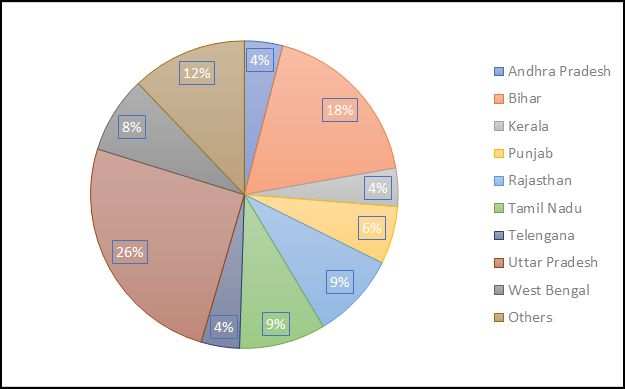

A second important change has been in the relative contribution by sending states of low-skilled workers to the Gulf labor market. Over the past decade, the number of blue collar Keralites migrating to the Gulf for work has plummeted by 90%. A recent study of migration trends and patterns focusing on Kerala — for decades a leading source of expatriate labor to the Gulf — concluded that “emigration from Kerala is falling and return migration is on the rise. The long history of migration from Kerala to the Gulf is in its last phase.”[19] Today, the space once occupied by Kerala is dominated by Uttar Pradesh (UP), Bihar, Rajasthan, and Tamil Nadu — the first three ranked as low-income states (LIS)[20] where declining job prospects in the formal and informal sectors appear to be feeding the growth in the number of workers heading to the Gulf. [See Figure 1.]

Figure 1. Distribution of Number of Indian Workers by Sending State, 2018

Source: GoI, Ministry of External Affairs, AR19.

Source: GoI, Ministry of External Affairs, AR19.

Troubles in “Paradise”

Over the past decade or more, the Indian government has been grappling with the downside risks associated with the migration to the Gulf of millions of its citizens. Yet, it is easy to lose sight of the challenges faced by blue collar Indian migrants themselves. The vast majority of the Indian expatriate workforce in the Gulf consist of temporary blue collar workers who have paid exorbitant recruitment fees to sell their labor[21] and whose precarious existence is defined by a foreign labor sponsorship system that formalizes their insecurity.

The Kafala system of foreign labor sponsorship, which ties workers to their employers, remains widespread in the Gulf States and has contributed to labor migrants’ precarity.[22] Some have criticized the system as being akin to “modern day slavery.”[23] Human rights groups have referred to it as “a maze of exploitation.”[24] Others have focused on the poor living conditions that migrants are forced to live in.[25] Complaints received from and on behalf of Indian workers have ranged from non-payment of salaries and denial of labor rights such as non-issuance or renewal of residence permits, to the refusal to pay overtime allowance or grant weekly holidays.[26] Hundreds have reportedly died of heat stress.[27] Added to these problems are those faced by Indian workers who have returned home following the expiration of their contracts and by those forced to return whether because they lack valid visas / work permits or for other reasons.

In recent years, the Government of India has taken a number of steps to strengthen the institutional framework for protecting migrants’ welfare.[28] On the domestic front, the Indian government has developed a suite of pre-departure, protection-during-work-abroad, and rehabilitation-upon-return migration safety awareness programs. On the ground in the Gulf, the GoI has established an Indian Workers’ Resource Center in Sharjah (UAE), to assist those who may be at risk of exploitation[29] and Community Welfare Funds, which levy small fees from consular services to support Indian nationals caught in crisis or other emergency.[30] These measures have been complemented by diplomatic efforts aimed at effecting reforms. Nevertheless, some regard the GoI’s various schemes as reactive and piecemeal responses[31] while others judge the reforms adopted by Gulf governments to address allegations of worker abuse to be incomplete and inadequate.[32]

A Testing Time

There have been several occasions in recent years when the Indian government has had to respond to contingencies requiring the repatriation and/or support of large numbers of distressed Indian workers in the Gulf.[33] Over a 30-month period in 2016-2018, the GoI had to manage the involuntary return of nearly one million Indian migrants from the Gulf.[34]

But neither the GoI nor Indian migrant workers in the Gulf have confronted anything of the magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic. The current situation is unprecedented, as it comprises both a public health emergency and an economic crisis that encompasses India and the Gulf region in their entirety.

The pandemic already has slammed shut the door at both ends of the India-Gulf migration corridor. Indian Embassies in the Gulf States swung into action with help lines and other measures to assist those stranded at airports.[35] Districts with high concentrations of migrants in the Gulf States such as Doha’s Industrial Area have been locked down.[36] Cramped accommodations and inadequate sanitation — circumstances in which social distancing is nearly impossible — heighten the health risks for many blue-collar workers. Fear of job loss renders them susceptible to unscrupulous employers who impossible choice of continuing to work or being forced to accept unpaid leave. Adding to the deep sense of personal insecurity faced by low-wage workers are the difficulties of contacting families in India due to restrictions on free internet calling.[37]

Meanwhile, in India, authorities have raced to put in place protocols for receiving returning workers. As of the second week of March, Telangana Health Department officials had begun screening all returning migrant workers arriving at Rajiv Gandhi International Airport in Hyderabad.[38] On March 18, an expanding compulsory quarantine at the port of first departure for a minimum period of 14 days for passengers coming from/transiting through UAE, Qatar, Oman, and Kuwait came into effect. With as many as 23 flights arriving daily from the Gulf, officials in Mumbai rushed to strengthen defenses by creating quarantine centers and administering tests for the estimated 26,000 asymptomatic (mostly blue collar) workers.[39]

One week later, on March 24, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced a 21-day nationwide lockdown to tackle the spread of the virus. As in all crises and disasters, vulnerable segments of the population are hardest hit. This became immediately apparent as millions of Indians who depend on each day’s wages for their daily meal have been thrown out of work[40] — including an estimated 120 million internal migrants.[41]

The disproportionately harmful effects of the pandemic on the Indian poor are bound to extend to Indian migrant workers in the Gulf, most of whom are also among the most vulnerable, by virtue of their occupation and skill profile, concentrated in low- and semi-skilled jobs.[42] Those workers who are in preventive quarantine or who have tested positive for the virus face the prospect of unpaid wages, arbitrary dismissal, and deportation. This precarious situation is arguably even more acute for the indeterminate number of workers who are irregular residents.

The large number Indian migrant workers who have not been repatriated face health and livelihoods risks.[43] The Gulf States have imposed stringent measures to contain the spread of the pandemic. Their healthcare systems, which are some of the most efficient in the wider MENA region, are freely and easily accessible to all citizens. However, it is important to note that the contagion risk is far higher in communities of foreign laborers, many of whom lack access to healthcare and live in conditions in which social distancing is not an option. Furthermore, as is true elsewhere where infection rates have climbed exponentially, Gulf medical facilities and healthcare professionals — including those of Indian origin, who constitute 57% of Saudi Arabia’s nursing staffs[44] — could quickly find themselves overwhelmed.

Although return migration is a predictable feature of temporary or contract migration, information to gauge its magnitude and impact is sparse. In the case of India, government agencies do not record the number of return migrants. Yet, it is nonetheless clear that the Coronavirus has imposed additional burdens on state authorities to screen and track recent returnees from the Gulf while taking steps to suppress rumors that might lead to the latter facing ostracism and discrimination. Moreover, returning workers who have lost their jobs will add to unemployment rolls in India.

Previous situations that have resulted in sudden job loss and large-scale returns from the Gulf (e.g., the financial crisis, 2007-2009; and Saudi Arabia’s Nitaqat policy, 2012) do not necessarily provide a clear guide as to how, much less how well returnees in the current context will be re-absorbed into their communities, what the impact of their reintegration will require of the Government of India and local authorities, and what the latter’s response capacities are.

Uncertain Future

The Coronavirus pandemic presents the dual challenge of a public health emergency and a socioeconomic crisis of extraordinary scale and scope. In the face of this challenge, the Government of India is navigating uncharted territory — bracing for a surge of infections; grappling with a shortage of healthcare workers, a lack of equipment, and a weak disease surveillance system; scrambling to devise ways to minimize the economic fallout; and struggling to develop a staggered exit strategy from a national lockdown which, while aimed at averting a humanitarian calamity inadvertently nearly induced one.

Meanwhile, the lives and livelihoods of the country’s 1.3 bllion people have been upended. At greatest risk are India’s legions of poor. On March 26, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced a US$23 billion relief package to mitigate the economic damage and to ease the financial pain of migrant workers, farmers, urban and rural poor, and women.[45] Whether this measure is adequate to address the plight of the marginalized and to rescue India’s struggling economy is unclear.

Equally unclear are the health and livelihoods prospects for India’s blue-collar workers in the Gulf and the future outlook for India-Gulf migration itself. A smooth return to business-as-usual after the travel ban ends is far from assured. The prospect that workers will reclaim their former jobs, much less that a fresh wave of aspiring job seekers will be absorbed into Gulf labor markets will depend on the duration and scope of the epidemic and the capacity of Gulf economies to recover.

Indian workers who do return to the Gulf are likely to be required upon arrival to present medical certificates from authorized hospitals — as Kuwaiti authorities have already mandated.[46] The threat of mass redundancies seems a distant possibility. However, once the COVID-19 crisis abates, the Gulf States could compel sweeping large-scale departures. A more likely scenario, though, is “a recalibration of reliance on foreign labor”[47] followed by a scaling back of government contracting and the levying of higher visa fees and employer taxes. Either eventuality would deal a heavy blow to the Indian economy as well as to the families and communities for which labor migration to the Gulf has long served as a lifeline.

No comments:

Post a Comment