NEW HAVEN: Over the past few decades, globalization represented the growing interdependence of economies, cultures and populations across the world, along with prosperity and rapid economic growth. Yet, modern globalization with liberal travel and trade also became a catalyst for the COVID-19 pandemic.

NEW HAVEN: Over the past few decades, globalization represented the growing interdependence of economies, cultures and populations across the world, along with prosperity and rapid economic growth. Yet, modern globalization with liberal travel and trade also became a catalyst for the COVID-19 pandemic.

Built on the theoretical foundations that champion specialization and international trade, most people were enthusiastic about a globalized community, and few cast doubt on the outgrowth of globalization. As economist Anne Krueger observed, “growth prospects for developing countries are greatly enhanced through an outer-oriented trade regime.” The value of global exports in 2007 was more than 20 times that of 1950. Benefitting from economic integration and outward-oriented trade regime, South Korea and China followed Japan’s rapid growth and became prosperous in their own right. Empirical evidence has corroborated the theoretical basis that globalization benefitted the rich and poor countries alike, despite some scholars pointing out how globalization has heightened inequality within countries. For example, China’s Gini coefficient increased from 0.25 in the mid-1980s to more than 0.45 in 2009 after its integration into the global system.

As the world submerged itself in the gains brought by cross-border tr ade of goods and services and the relatively free flow of people, imbalances and cracks emerged. The associated dangers went largely neglected. Since 2008, a spate of misfortunes has weighed on globalization, including the global financial, refugee and climate change crises. An interconnected world means shared risks and people could not detach themselves from crisis. The global trade imbalance is one of the most prominent problems. The United States has run a continuous current account deficit since the 1980s, while Japan, Korea and China have gained surplus. The imbalance in trade has been a major headwind against globalization resulting in a series of skirmishes, peaked by the US-China trade war that began in 2018.

With the United States and China exchanging aggressive rhetoric, most recently blaming each other for COVID-19, the trade war's end is not within the foreseeable future. The world’s two largest economies have traded less since mid-2018, dampening optimism for globalization. The US and China traded $635 billion and $659.8 billion worth of goods in 2017 and 2018, respectively. Trade volume substantially dropped to $558.9 billion in 2019, a decrease of 15.3 percent. Rising protectionism against free trade and migration in the US, the world’s largest economy, erodes globalization’s luster and ravages people’s belief in a prosperous globalized community.

Furthermore, the pandemic, which emerged in Hubei, China, in November, is a double whammy to the already fragile global system, bringing economies and globalization to a near-complete halt. COVID-19 has infected more than 2 million people, killing more than 130,000 globally with astonishing pace. The devastating pandemic, with its high mortality rate and so many displaying mild or no symptoms at all, shows little sign of waning. Globalization along with convenient and affordable transportation is a major reason that the disease spread to virtually every country in the world in a few short months. The liberal flow of people and commodities, once a major driving force of prosperity, transformed into a sprawling behemoth that could ruin lives of countless human beings.

Although media closely followed the outbreak with truthful reports and clear warnings that offered a chance at containing the virus, policymakers paid little attention. According to a January 23 CNN news report, Charles Li, CEO of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, said in Davos that he hoped the world could react better to the coronavirus than it did to the SARS outbreak, referencing governments, institutions, hospitals and the media. The Washington Post also reported that US intelligence agencies warned President Donald Trump about an impending pandemic as early as November. Even the devastation in China and then Italy failed to alarm most policymakers.

By March 30, however, most European countries were on lockdown to curb the spread of the virus, and other countries soon joined. Australia limited public gatherings to just two people, while New Zealand’s nationwide isolation began March 25. Most US states issued stay-at-home orders for more than 250 million people, and by mid-April only seven refused to comply. Countries try closing borders for non-nationals, while global major airlines have eliminated most international flights. In the world’s once crowded and profitable route between London and New York, passengers number in the single digits.

Making matters worse, the pandemic still accelerates, while globalization is in retreat. People cannot avoid asking: What went wrong with globalization? Could some reversals become permanent?

Strengthening multilateral cooperation is key to maintaining prosperity. Globalization is crippled, but not fatally wounded. The lessons from the Great Depression almost a century ago proved that anti-globalization and protectionism are not antidotes to sluggish economic growth. Instead, international trade and mobilization of resources offer strong momentum for growth in the developing world while also benefiting consumers in developed countries with low-cost imported commodities.

The root cause of the chaos lies in the laggard, obsolete international organizations as well as poor global governance. Amid the spreading virus, the World Health Organization, which aims to “prepare for emergencies by identifying, mitigating and managing risks,” could only issue advice to sovereign countries while lacking authority to implement tangible measures. In addition, WHO’s COVID-19 response was insufficient. China first reported the new virus to WHO on December 31, three weeks after doctors tried raising alarm. Even after China took draconian measures to lock down the city of Wuhan, WHO failed to provide useful, urgent recommendations throughout January to tackle the new contagious disease.

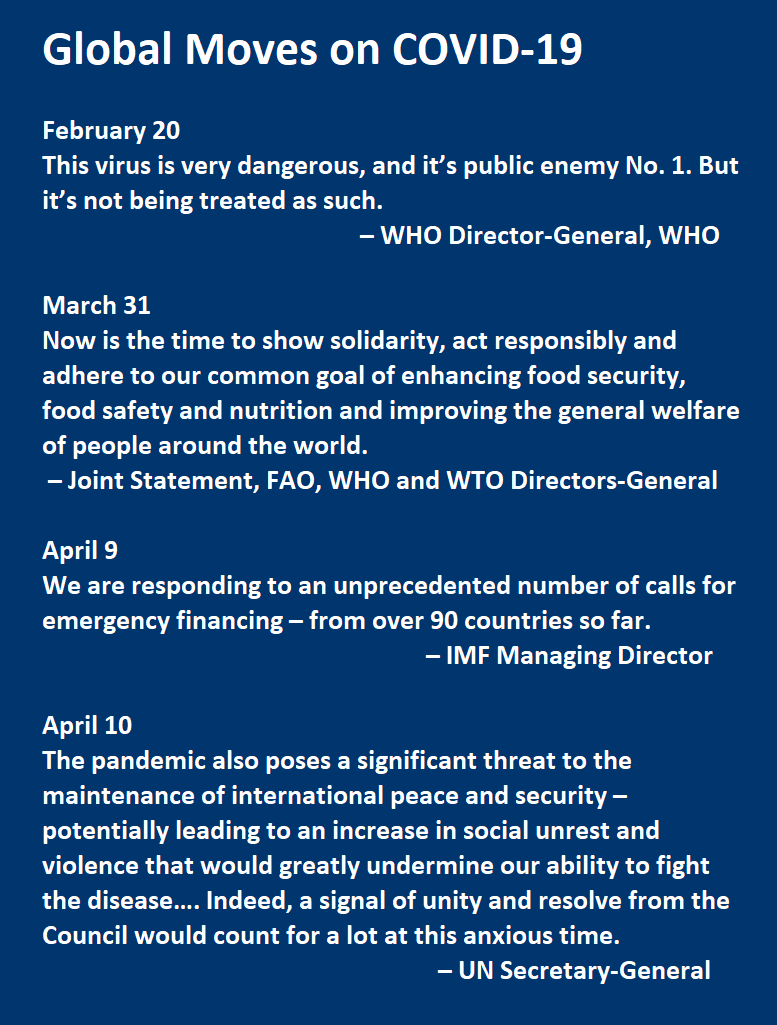

Of course, WHO is not the only culprit pushing the crisis beyond repair. Instead, weak inter-country cooperation and international institutions’ lack of authority perhaps bear the most responsibility. Some politicians may blame WHO for belatedly declaring a pandemic on March 11. Still, WHO undertook a number of measures to contain the disease. On February 11, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus called the outbreak a “very grave threat for the rest of the world,” and sent another warning on February 20: “This virus is very dangerous, and it’s public enemy No. 1. But it’s not being treated as such." One day later, he emphasized that the window of opportunity to contain the outbreak is “narrowing.”

Only a few days later, leaders of the second and third most populous countries in the world, Narendra Modi and Donald Trump, held a joint rally in India attended by more than 100,000 people. Trump insisted COVID-19 was “very well under control in our country.” Likewise, UK Health Secretary Matt Hancock suggested that the risk to the UK population was low and “we are well prepared and well equipped.”

During the one-month window period to contain the epidemic, from WHO first ringing the alarm on February 11 to Italy’s implementation of nationwide lockdown on March 9, the international community failed to take effective measures either due to confidence in domestic healthcare systems or fear that halting economic activities might exhaust already weak economic growth. Myopic complacency and undue pursuit of economic growth blinded policymakers and made global outbreak inevitable.

Today, behind ascending numbers of cases and deaths, millions of people suffer from the disease or the loss of livelihoods. Meanwhile, diplomats and politicians continue to disregard advice from professionals and cling to conspiracy theories.

Donald Trump announced suspension of US funding for WHO pending an investigation, but he should act to strengthen rather than weaken such organizations.

Globalization is not the culprit, but rather the lack of strong international organization and effective cooperative mechanisms, with unified messages based on the best science. To salvage the fragmented system, the international community must reflect on the existing framework to resolve global crises and strengthen the leadership role of international organizations in emergencies. In particular, WHO should take the lead in the current pandemic, while countries should implement serious policies based on WHO recommendations. Instead of each country fighting its own battle, there is pressing need to set up a joint ministerial committee under WHO's leadership as a decision-making body to contain the virus with cooperative efforts.

The world will eventually tide over this pandemic, but if steps are not taken to improve global governance, COVID-19 will not be the last pandemic that devastates globalization.

Hans Yue Zhu is a graduate student at Yale University’s economics department and a research assistant at the Yale Jackson Institute for Global Affairs focusing on public policy and development economics. His research touches on China’s economic reforms and its macroeconomic efficiency.

This article was published April 15, 2020.

No comments:

Post a Comment