Aaron E. Carroll

While many watched the coronavirus spread across the globe with disinterest for months, in the last week, most of us have finally realized it will disrupt our way of life. A recent analysis from Imperial College is now making some Americans, including many experts, panic. The report projects that 2.2 million people could die in the United States. But the analysis also provides reason for hope—suggesting a path forward to avoid the worst outcomes.

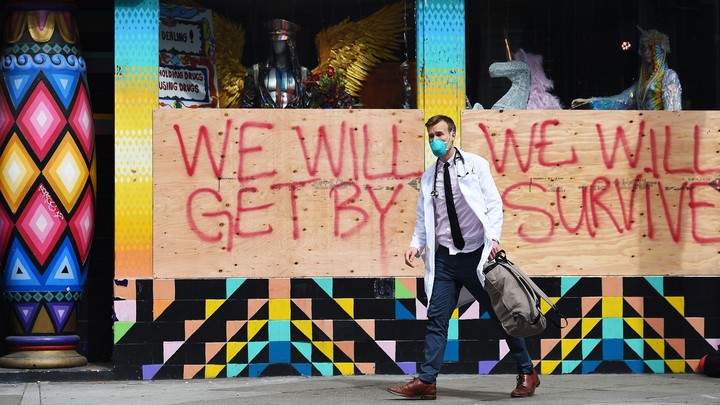

We can make things better; it’s not too late. But we have to be willing to act.

Let’s start with the bad news. The Imperial College response team’s report looked at the impact of measures we might take to flatten the curve, or reduce the rate at which people are becoming sick with COVID-19. If we do nothing and just let the virus run its course, the team predicts, we could see three times as many deaths as we see from cardiovascular disease each year. Further, it estimated that infections would peak in mid-June. We could expect to see about 55,000 deaths, in just one day.

Of course, we are doing something, so this outcome is unlikely to occur. We’re closing schools and businesses and committing to social (really, physical) distancing. But as the sobering charts from the analysis show, this isn’t enough. Even after we do these things, the report predicts that a significant number of infections will occur, that more people will need care than we can possibly provide in our hospitals, and that more than 1 million could die.

Why does the Imperial College team predict this for the West when things seem to be improving in Asia? Because we are taking different approaches. Asian countries have engaged in suppression; we are only engaging in mitigation.

Suppression refers to a campaign to reduce the infectivity of a pandemic, what experts call R0 (R-naught), to less than one. Unchecked, the R0 of COVID-19 is between 2 and 3, meaning that every infected person infects, on average, two to three others. An R0 less than 1 indicates that each infected person results in fewer than one new infection. When this happens, the outbreak will slowly grind to a halt.

To achieve this, we need to test many, many people, even those without symptoms. Testing will allow us to isolate the infected so they can’t infect others. We need to be vigilant, and willing to quarantine people with absolute diligence.

Because we failed to set up a testing infrastructure, we can’t check that many people. At the moment, we can’t even test everyone who is sick. Therefore, we’re attempting mitigation—accepting that the epidemic will advance but trying to reduce R0 as much as possible.

Our primary approach is social distancing—asking people to stay away from one another. This has meant closing schools, restaurants, and bars. It’s meant asking people to work from home and not meet in groups of 10 or more. Our efforts are good, temporizing measures. Impeding the growth of the infection improves the chance our health-care system will be able to keep up.

But these efforts won’t help those who are already infected. It will take up to two weeks for those infected today to show any symptoms, and some people won’t show symptoms at all. Social distancing cannot prevent these infections, as they’ve already happened. Therefore, things will appear to get worse for some time, even if what we’re doing is making things better in the long run. The outbreak will continue to progress.

But buried in the Imperial College report is reason for optimism. The analysis finds that in the do-nothing scenario, many people die and die quickly. With serious mitigation, though, many of the measures we’re taking now slow things down. By the summer, the report calculates, the number of people who become sick will eventually reduce to a trickle.

On this path, though, the real horror show will begin in the fall and crush us next winter, when COVID-19 comes back with a vengeance.

This is what happened with the flu in 1918. The spring was bad. Over the summer, the numbers of sick dwindled and created a false sense of security. Then, all hell broke loose. In late 1918, tens of millions of people died.

If a similar pattern holds for COVID-19, then while things are bad now, it may be nothing compared to what we face at the end of the year.

Because of this, some are now declaring that we might be on lockdown for the next 18 months. They see no alternative. If we go back to normal, they argue, the virus will run unchecked and tear through Americans in the fall and winter, infecting 40 to 70 percent of us, killing millions and sending tens of millions to the hospital. To prevent that, they suggest we keep the world shut down, which would destroy the economy and the fabric of society.

But all of that assumes that we can’t change, that the only two choices are millions of deaths or a wrecked society.

That’s not true. We can create a third path. We can decide to meet this challenge head-on. It is absolutely within our capacity to do so. We could develop tests that are fast, reliable, and ubiquitous. If we screen everyone, and do so regularly, we can let most people return to a more normal life. We can reopen schools and places where people gather. If we can be assured that the people who congregate aren’t infectious, they can socialize.

We can build health-care facilities that do rapid screening and care for people who are infected, apart from those who are not. This will prevent transmission from one sick person to another in hospitals and other health-care facilities. We can even commit to housing infected people apart from their healthy family members, to prevent transmission in households.

These steps alone still won’t be enough.

We will need to massively strengthen our medical infrastructure. We will need to build ventilators and add hospital beds. We will need to train and redistribute physicians, nurses, and respiratory therapists to where they are most needed. We will need to focus our factories on turning out the protective equipment—masks, gloves, gowns, and so forth—to ensure we keep our health-care workforce safe. And, most importantly, we need to pour vast sums of intellectual and financial resources into developing a vaccine that would finally bring this nightmare to a close. An effective vaccine would end the pandemic and protect billions of people around the world.

All of the difficult actions we are taking now to flatten the curve aren’t just intended to slow the rate of infection to levels the health-care system can manage. They’re also meant to buy us time. They give us the space to create what we need to make a real difference.

Of course, it all depends on what we do with that time. The mood of the country has shifted in the last few weeks, from dismissal to one of fear and concern. That’s appropriate. This is a serious pandemic, and it’s still very likely that the rate of infection will overwhelm the surge capacity in some areas of the United States. There will likely be more seriously ill people than we have resources to care for, meaning that providers will have to make decisions about whom to treat, and whom not to.

They may, explicitly or implicitly, have to decide who lives and who dies.

If we commit to social distancing, however, at some point in the next few months the rate of spread will slow. We’ll be able to catch our breath. We’ll be able to ease restrictions, as some early hit countries are doing. We can move toward some semblance of normalcy.

The temptation then will be to think we have made it past the worst. We cannot give in to that temptation. That will be the time to redouble our efforts. We will need to prepare for the coming storm. We’ll need to build up our stockpiles, create strategies, and get ready.

If we choose the third course, when fall arrives, we will be ahead of a resurgence of the infection. We can keep the number of those who are exposed to a minimum, focusing our attention on those who are infected, and enacting more stringent physical distancing only when, and in locations where, that fails. We can keep schools and businesses open as much as possible, closing them quickly when suppression fails, then opening them back up again once the infected are identified and isolated. Instead of playing defense, we could play more offense.

We need to keep time on the clock, time to find a treatment or a vaccine.

The last time we faced a pandemic with this level of infectivity, that was this dangerous, for which we had no therapy or vaccine, was a 100 years ago, and it led to 50 million deaths. The coronavirus pandemic isn’t unprecedented, but it’s not anything almost anyone alive has experienced before. We, are, however, much more knowledgeable, much more coordinated, and much more capable today.

Some Americans are in denial, and others are feeling despair. Both sentiments are understandable. We all have a choice to make. We can look at the coming fire and let it burn. We can hunker down, and hope to wait it out—or we can work together to get through it with as little damage as possible. This country has faced massive threats before and risen to the challenge; we can do it again. We just need to decide to make it happen.

No comments:

Post a Comment