TRINH NGUYEN

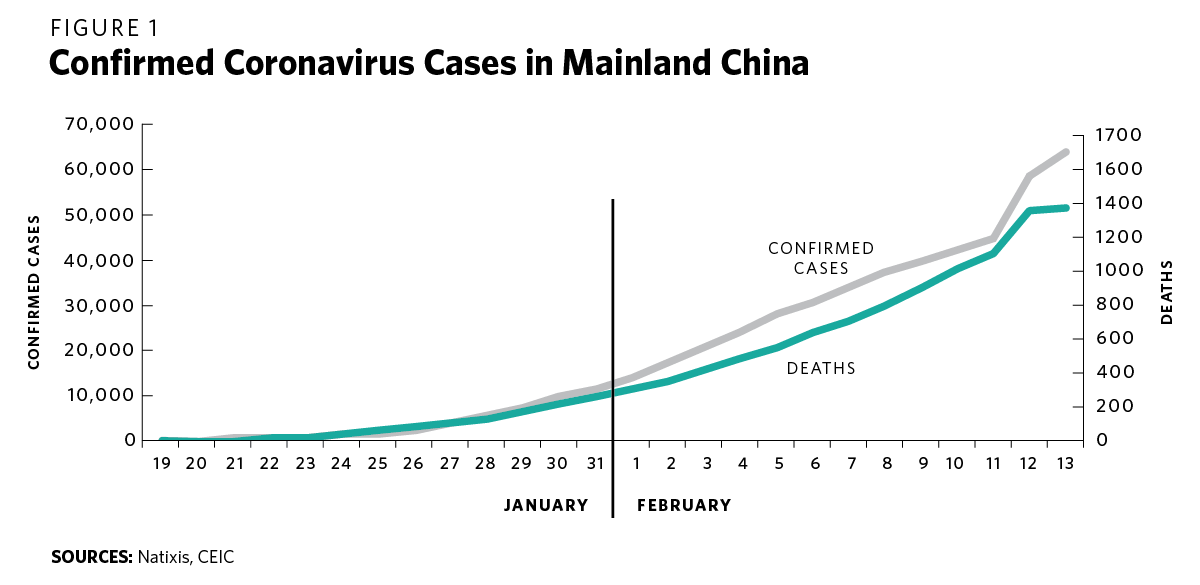

The world watches as the number of confirmed coronavirus cases continues to climb. But at more than 1,000 fatalities and counting, the new virus strain has already claimed more total lives than the 2002–2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak, according to data from CEIC (see figure 1). That said, a lower share of people who have contracted the 2019–2020 coronavirus have died, a figure that hovers around 2 percent.

To contain the virus’s rapid spread, authorities in China have locked down Hubei Province, where the outbreak was first reported, and have restricted economic activities in the rest of China. Some other countries have curbed travel to mainland China, including Australia, the United States, the Philippines, and Vietnam.

Quarantine measures may have helped keep the virus from spreading even faster, but they have also stymied economic activity. The virus’s ripple effects have hampered the economies of nearby countries, especially in Southeast Asia, in three main ways: by curtailing the number of Chinese tourists, disrupting China-centric supply chains, and putting a damper on economic demand in China.

1. FEWER CHINESE TOURISTS

The viral outbreak has revealed that several Southeast Asian countries are heavily dependent on Chinese tourism (see figure 2). Travel bans and restrictions have bottled up the flow of tourists since the Lunar New Year holiday. Tourism-related industries such as transportation and hospitality have been hit particularly hard.

The impact will be felt most acutely by Thailand, which has already been contending with a sluggish economy due to an aging population and weak domestic investment. But other Southeast Asian countries will also be affected, including Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. Their high dependence on tourists from China and from other countries more generally means that the outbreak will have a deep impact on their economies.

2. DISRUPTED MANUFACTURING SUPPLY CHAINS

China’s economic footprint is much bigger now than it was nearly two decades ago. When SARS hit in 2002 and 2003, China was the source of 8 percent of all the manufacturing goods exported worldwide, according to the UN Conference on Trade and Development. By 2018, this figure had ballooned to 19 percent (see figure 3).

In a lopsided fashion, the world has become more dependent on China economically, even as China has become less dependent on the rest of the world. Many countries now import more Chinese-made intermediate goods, which they then use as components to make finished goods to be shipped overseas. This means that any disruptions to Chinese manufacturing supply chains often create enormous global domino effects.

Meanwhile, China has held its own economic vulnerability vis-à-vis other countries in check (see figure 4). Across many manufacturing sectors, the country has managed to remain increasingly self-sufficient. It now imports fewer intermediate goods from the rest of the world by vertically integrating supply chains, except in the cases of some raw materials like oil and certain high-tech goods, such as semiconductors.

The viral outbreak and the resulting quarantines have disrupted many supply chains involving China. For example, the huge electronics manufacturer Foxconn, which makes Apple iPhones, resumed production on February 10, 2020, but on a very limited scale.

Other countries’ dependence on Chinese capital and intermediate goods is leaving them scrambling for alternatives (see figure 5). This will be an even tougher challenge for sectors in which China has larger market shares, such as electronics and automobiles.

Figure 6 projects the damage that Southeast Asian countries will have to weather if 20 percent of Chinese manufacturing were to remain shuttered for a full quarter. If factories were to fully reopen in one month, the impact would be much less.

Vietnam will be affected the most due to its high dependence on Chinese supply chains, but its sharp overall growth rate—more than 7 percent in 2019—provides a partial buffer. Meanwhile the impact on the economies of Hong Kong and Singapore will be more severe, given that they were already experiencing a slow pace of growth due to structural weaknesses even before the crisis unfolded.

What’s more, even though the projected decline in expected gross domestic product (GDP) growth is lowest for Japan (see figure 6), the impact will be larger in some respects because it is the largest economy in Asia outside of China. That means the nominal GDP value of even a smaller percentage-point economic disruption would still be relatively high. In fact, based on calculations using CEIC data, the expected relative drop in the total value of GDP growth for Japan is expected to be the second highest among China’s neighbors, behind only that of South Korea. From that vantage point, South Korean and Japanese firms will feel the biggest impact.

Indirectly, Japan and South Korea are also exposed by virtue of their stock investments in Southeast Asia and, of course, mainland China. Northeast Asian economies have been trying to avoid the risk of investing too heavily in China by diversifying their investments into Southeast Asia. Still, the amount of Japanese and South Korean foreign direct investment in mainland China remains large and is greater than the size of the countries’ investments in Southeast Asia, according to data from CEIC and WIND (see figure 7).

The full-on shutdown of Hubei and reduced economic activity in other Chinese provinces like Guangdong is directly hitting Northeast Asian production lines. Indirectly, Northeast Asian corporations are further hit via large investments in Southeast Asia that depend on Chinese inputs for manufactured finished goods. And third, of course, are the disruptions to the production of imported components such as auto parts.

In other words, Northeast Asia’s exposure to mainland China and Southeast Asia through investments means that the supply chain impact on Vietnam is felt heavily by major Northeast Asia corporations such as Samsung and Sony.

Asia’s electronics, automobile, machinery, and textile sectors will be most affected by disruptions to Chinese supply chains due to their sheer economic value and high dependence on the stalled production of Chinese inputs. What is bad news for mainland China impacts Southeast Asia and, as a result, is bad news for Northeast Asian firms, which make a lot of electronics, machinery, and auto parts.

3. LESS CHINESE DEMAND

With fewer Chinese travelers venturing abroad and Chinese supply chains in disarray amid the upheaval of the coronavirus outbreak, there are also fewer Chinese consumers buying new goods and services. That means if transportation hubs, retail outlets, and factories are shut down or limited in operations for more than a short time, the impact on growth will also be massive.

Just as with tourism and manufacturing, Asia has become more reliant on Chinese demand as a source of growth since SARS struck in 2002 and 2003. The most exposed economies include Vietnam, Taiwan, Singapore, South Korea, and Malaysia (see figure 8).

Southeast Asia is very susceptible to the economic fallout of the coronavirus in an array of sectors, including tourism and manufacturing, as well as due to dampened Chinese demand. Economies that have increased their dependence on China, such as Thailand (due to tourism) and Vietnam (due to exports and supply chain linkages), will be the worst hit.

The coronavirus has revealed some cracks in Southeast Asia’s growth models. Many of China’s neighbors have leaned too heavily on external demand and China-centric supply chains to drive their own domestic economic growth.

In the short term, central banks in Southeast Asia will likely opt to cut interest rates and allow their currencies to weaken in order to make their countries’ exports more competitive. Governments will also likely roll out miniature stimulus packages to offset the drag.

That said, beyond these short-term measures, the economies of Southeast Asia must make more drastic reforms. They should invest in their domestic capacities to produce more lucrative goods and services. That way, they can capture a greater share of global supply chains. And they should also invest more in domestic sources of growth. Too much reliance on external sources of prosperity can bite back.

No comments:

Post a Comment