By Ankit Panda

Along with much of Central Asia, Iran, and parts of the Middle East, Afghanistan celebrates the Nowruz New Year festival this week. Nowruz is a time to celebrate springtime, rebirth, and new beginnings. In the aftermath of the historic February 29 U.S.-Taliban deal, it certainly has felt as if Afghanistan is due to see the start of a new era in its history. Taliban leader Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar sat down next to Zalmay Khalilzad, the U.S. peace envoy, in Doha, Qatar, that day and the two signed an agreement that appeared to hold the key to ending almost 19 years of continuous war.

Along with much of Central Asia, Iran, and parts of the Middle East, Afghanistan celebrates the Nowruz New Year festival this week. Nowruz is a time to celebrate springtime, rebirth, and new beginnings. In the aftermath of the historic February 29 U.S.-Taliban deal, it certainly has felt as if Afghanistan is due to see the start of a new era in its history. Taliban leader Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar sat down next to Zalmay Khalilzad, the U.S. peace envoy, in Doha, Qatar, that day and the two signed an agreement that appeared to hold the key to ending almost 19 years of continuous war.

If you missed it, the contours of the deal are fairly straightforward, even if the details are not. The United States has agreed to gradually withdraw its forces in Afghanistan over a period of 14 months provided that the Taliban prevent terrorist groups, including al-Qaeda, from using territory under their control to stage operations or attacks.

The Afghan government, which wasn’t party to the deal, has assented to its existence, but what has become clear in the three weeks since the signing ceremony is that implementation won’t be easy. While the United States might be able to leave Afghanistan, the Afghan people themselves might not find the peace they seek too easily.

Two major issues deserve attention. The first pertains to a prisoner release that had been agreed as part of the deal. One of the reasons the Taliban agreed to the February 29 pact was because it included a provision for the release of up to 5,000 prisoners held by the Afghan government.

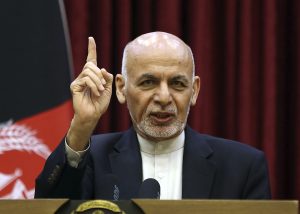

Kabul has been circumspect about this provision, with President Ashraf Ghani initially reticent about releasing any prisoners, but eventually agreeing to release 1,500 in a staggered manner. One logjam now is that Ghani refuses to budge further until the Taliban begin talks in good faith with the Afghan government; the Taliban have treated this as a no-go. Read The Diplomat‘s Catherine Putz on the U.S. approach to bridging this gap.

Meanwhile, violence persists in Afghanistan, even if it isn’t directed by the Taliban at U.S. forces to keep the February 29 deal mostly intact. In the first few days after the signing, dozens of small-scale attacks carried out by Taliban fighters against Afghan forces took place, raising concerns that the group might have opportunistically used the opening with the Trump administration to engineer an American withdrawal that would leave Kabul more vulnerable than ever. Even as the United States was talking to the Taliban in the past, it was able to provide Afghan forces with close air support, intelligence, and operational assistance. Once withdrawal occurs, that much won’t be possible. Critics of the American deal with the Taliban have drawn parallels to the Nixon administration’s deal with North Vietnam, fearing a “Fall of Saigon” moment in Kabul in a matter of a few years, if not sooner, if the Taliban are able to overwhelm Afghan forces.

The Afghan government is under tremendous pressure to find a way to best manage its interests after the February 29 deal. What is looking clearer is that the Trump administration is ready to wash its hands of Afghanistan, hoping to file away the Leap Day Deal as a major foreign policy success—perhaps even something that can be touted in an election year. Trump had once promised as a presidential candidate to end U.S. overseas entanglements and keeping this deal alive will be presented to his base as a delivery on that promise.

For the Taliban, all of this presents a tremendous opportunity. If the group is able to avoid missteps that would assuredly invite an American rethink of the February 29 deal (such as a major, high casualty attack on U.S. and NATO forces), it might see great opportunity. The Afghan government continues to face several vulnerabilities as well, including the growing specter of a serious COVID-19 outbreak in the country and the lingering legitimacy crisis arising from the parallel presidential inauguration undertaken by former Chief Executive Abdullah Abdullah (who was deemed to have lost the September 2019 presidential election according to the country’s election commission).

If March 2020 marks a new start for Afghanistan, it certainly doesn’t appear to be all that auspicious.

To read the entirety of the latest edition of the APAC Risk Newsletter, presented by Diplomat Risk Intelligence, click here to read and subscribe for free.

No comments:

Post a Comment