By Yan Yan

The South China Sea Probing Initiative (SCSPI) a project of the Peking University Institute of Ocean Research, recently released Automatic Identification System (AIS) data showing more than 300 Vietnamese fishing boats gathering in the near seas of China’s Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan provinces in February — while China is busy fighting the coronavirus.

Illegal fishing from Vietnam is a long-standing problem. Even with a nearly 3,500 kilometer coastline, fish stocks in Vietnam’s near sea are depleting, and its fishermen have been trying to venture farther away to catch fish in the past years. The European Commission (EC) applied a yellow card warning on seafood from Vietnam in 2017 due to the failure of to prevent illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing. The warning came out especially after a number of Vietnamese fishing fleets were caught illegally fishing in other countries’ waters.

Although Deputy Prime Minister Trinh Dinh Dung demanded that all related parties prevent illegal fishing in other countries’ waters after the EC decided to extend the yellow card in 2019, the situation hasn’t changed much. Vietnamese government officials have mentioned in the past that it is difficult to catch the illegal trawlers operating at sea since there are too many of them, and their engine capacity reaches 500-800 horsepower.

Recently Malaysia also reported an increase in the number of Vietnamese fishing vessels encroaching into its exclusive economic zone (EEZ), off the country’s east coast, in the past few months. Malaysia protested to Vietnam and is now seeking a bilateral agreement to solve the problem. Last year 141 Vietnam fishermen were detained by Malaysian authorities.

China declared its baselines on May 15, 1996, based on the 1992 Law on Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone. The 12 nautical mile territorial sea around Hainan Island as well as Guangdong and Guangxi provinces is of no dispute between the two neighbors.

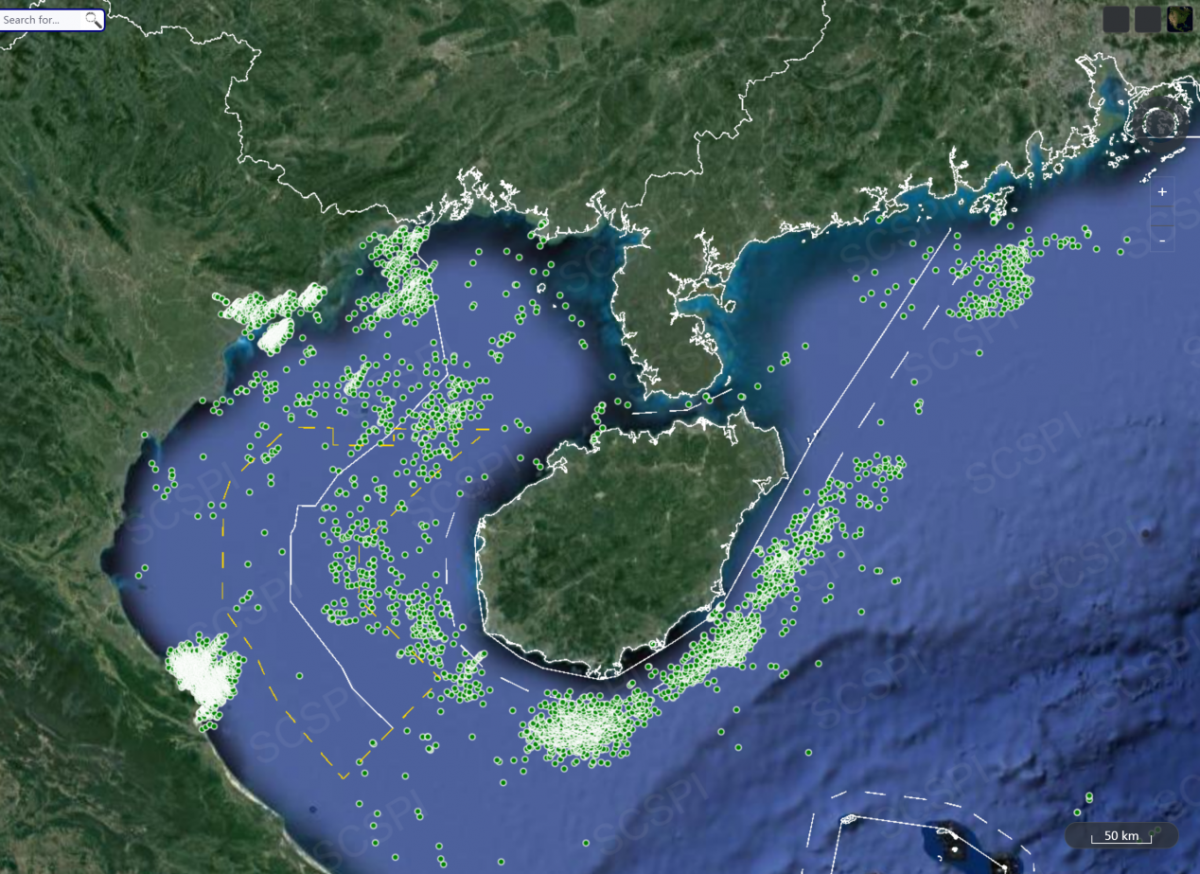

China and Vietnam settled a maritime boundary in the Gulf of Tonkin and a fishery cooperation agreement on December 25, 2000. However the AIS image from SCSPI shows that two-thirds of Vietnamese fishing vessels are on the Chinese side of the boundary line (the solid white line in the map below). Some of them may have a license to fish in the common fishing zone, but more than half of the boats are outside the zone (denoted by the dashed yellow line).

Map from the South China Sea Probing Initiative. Each green dot represents a Vietnamese fishing boat registered in the AIS during February 2020.

The AIS information shows that there are around 200 Vietnam fishing vessels surrounding the east coast of China’s Hainan province, many of them operating within 12 nautical miles of Sanya and Qionghai city (depicted by the white dashed line in the map above). Many analysts suspect that besides illegally fishing in China’s EEZ, Vietnamese fishing vessels are collecting intelligence on China’s military bases as well as naval and air military activities.

Sanya is located at the southern end of Hainan island. It is a picturesque city and famous tourist destination in the region. More relevant to this incident, however, is the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy’s Yulin Naval Base, located at the southernmost tip of Sanya. Yulin is often referred to as the most strategically important base in the South China Sea. The Lingshui military airport – where a U.S. EP-3 reconnaissance aircraft landed after a fatal collision with a Chinese jet in 2001 — is also very close to Sanya.

SCSPI revealed that some of the fishing vessels suspiciously changed their status from “fishing vessel” to “merchant ship” on the AIS, seemingly a bid to hide their identity. Considering Vietnam is building a strong maritime militia force, it’s reasonable to think that many of these 200 vessels could be maritime militia.

The deputy defense minister of Vietnam, Colonel General Phan Van Giang, in December 2019 said that Vietnam was setting up its maritime militia, starting with six southern provinces and expanding to 14 provinces across the country. The goal is twofold: “sovereignty protection and economic development.” Hanoi has also revised the 2009 Law on Militia and Self-Defense Forces to provide a legal basis for the maritime militia. The new version will be enacted in July 2020.

Since most of Vietnam’s maritime militia is comprised of local fishermen, neighboring countries find it extremely difficult to distinguish between the two. It is reported that Vietnamese banks have loaned $176 million to fishermen to upgrade about 400 ships. More than 10,000 fishermen received infrared night vision binoculars and firearms.

In 2018, Vietnam set the goal of becoming a strong maritime power by 2030 in a resolution passed by its Communist Party Central Committee. By doing so, Vietnam hopes to boost its maritime economy and strengthen national defense to protect its maritime rights. In the fourth version of its defense white paper, released on November 25, 2019, Vietnam described itself as a maritime nation, and said the safety and protection of its surrounding seas is of critical importance.

In pursuit of its maritime dream, Vietnam should not turn a blind eye to its fishing vessels illegally fishing or collecting intelligence in a neighbor’s territorial sea. Last July, Vietnam’s new Law on Coast Guards was put into effect. Many measures have been taken domestically to enhance the role and operational flexibility of Vietnam’s Coast Guard throughout the years. It is time for them to deal with Vietnamese boats illegally fishing in other country’s waters.

Being the ASEAN chair in the year 2020, Vietnam’s maritime practice will be closely watched by all the countries in the region, especially South China Sea bordering states. Confidence in Vietnam’s role as chair will be built not only on how it could lead ASEAN to new developments, but also how it handles its fishermen and fishing vessels domestically.

Dr. Yan Yan is Director of the Research Center for Oceans Law and Policy, National Institute for South China Sea Studies (NISCSS), China.

No comments:

Post a Comment