by Emerson T. Brooking, Suzanne Kianpour

Tens of thousands of Iranians took to the streets to protest irregularities in the 2009 Iranian presidential election. These protests soon became known as the “Green Movement.” In their aftermath, Iranian authorities began to infiltrate and co-opt the digital platforms used by democratic activists.

Tens of thousands of Iranians took to the streets to protest irregularities in the 2009 Iranian presidential election. These protests soon became known as the “Green Movement.” In their aftermath, Iranian authorities began to infiltrate and co-opt the digital platforms used by democratic activists.

Iran has invested significant resources and accumulated vast experience in the conduct of digital influence efforts. These clandestine propaganda efforts have been used to complement Iranian foreign policy operations for the better part of a decade. Nonetheless, Iranian influence capabilities have gone largely unstudied by the United States, and only came to widespread attention in August 2018 with the first public identification of an Iranian propaganda network. Following the US assassination of Iranian Major General Qasem Soleimani and a sharp escalation in US-Iranian tensions, it is important to understand the perspective, methods, and intent of Iranian influence efforts.

For Iran, information dominance represents a central focus of both foreign and domestic policy. Iran sees itself as engaged in a perennial information war: against Sunni Arab powers, against the forces of perceived Western neocolonialism, and particularly against the United States. Should the information conflict be lost, many Iranian officials believe the collapse of the state will soon follow. Accordingly, Iran has prioritized the development of digital broadcast capabilities that cannot be easily targeted by the United States or its allies.

Iran has also prioritized information control. Although Iran boasts roughly fifty-six million Internet users, these users must navigate a culture of censorship and frequent state intimidation. Following the 2009 Green Movement, the Iranian government came to see social media activism as enabling an existential threat. Authorities created special cyber-police units, built a new legal framework for Internet regulation, and outlawed most Western digital platforms. They also began to develop systems to remove Iranian users from the global Internet entirely.

In pursuit of foreign and domestic information dominance, Iran began operating Facebook and Twitter sockpuppets as early as 2010. As the United States and Iran entered into a period of rapprochement and negotiation, the number of accounts grew exponentially. These accounts have been used to launder Iranian state propaganda to unsuspecting audiences, often under the guise of local media reports. To date, Facebook has identified approximately 2,200 assets directly affecting six million users. Twitter has identified eight thousand accounts responsible for roughly 8.5 million messages.

Much of this Iranian content cannot be characterized as “disinformation.” In sharp contrast to the information operations of Russia, which routinely disseminate false stories with the aim of polluting the information environment, Iran makes less use of obvious falsehood. Instead, Iran advances a distorted truth: one that exaggerates Iran’s moral authority while minimizing Iran’s repression of its citizens and the steep human cost of its own imperial adventures in the wider Middle East.

As a whole, Iran’s digital influence operations represent a continuation of public diplomacy, albeit conducted through misleading websites and social media sockpuppets. Iran broadcasts a fairly consistent message to many different audiences: in Africa, in Southeast Asia, in Europe, in North America, and, most notably, in Latin America and the Middle East. The aim of these efforts is to “tell Iran’s story,” the same as any Western government broadcaster might strive to do. The difference is that, as an international pariah, Iran must pursue this work through more clandestine means. Global observers have long learned to doubt the truthfulness and sincerity of Iranian-branded media.

As the United States considers policies to safeguard its elections and confront Iranian influence activities, three conclusions can be drawn about the nature of Iran’s modern propaganda apparatus.

Iran’s digital influence efforts involve centralized goals and disparate agents. Different elements of Iran’s digital propaganda apparatus evidence the involvement of different government agencies. It is not clear how, or if, these agencies coordinate their operations.

These goals are closely tied to Iran’s geopolitical interests. Nearly all content spread by Iran’s digital influence efforts relates directly to its worldview or specific foreign policy objectives. Consequently, it is easier to identify the operations of Iran than those of other actors like Russia, whose content is more likely to be politically agnostic.

Iran may attempt direct electoral interference in 2020 and beyond. To date, there is little evidence that Iran has sought to affect the outcome of a US election. This does not, however, preclude future such campaigns based on Iranian interest in achieving rapprochement with the United States.  As US-Iranian tensions sharply escalated in January 2020, Iranian Instagram accounts spammed the White House and members of the Trump family with images of flag-draped coffins. Source: Kanishk Karan/Instagram

As US-Iranian tensions sharply escalated in January 2020, Iranian Instagram accounts spammed the White House and members of the Trump family with images of flag-draped coffins. Source: Kanishk Karan/Instagram

As US-Iranian tensions sharply escalated in January 2020, Iranian Instagram accounts spammed the White House and members of the Trump family with images of flag-draped coffins. Source: Kanishk Karan/Instagram

As US-Iranian tensions sharply escalated in January 2020, Iranian Instagram accounts spammed the White House and members of the Trump family with images of flag-draped coffins. Source: Kanishk Karan/Instagram

Additionally, five steps can be taken to better prepare the United States to meet this threat.

The US Global Engagement Center (GEC) should invest resources in identifying and neutralizing—but not editorializing about—Iran’s digital influence networks. Through its funding of the Iran Disinformation Project, an independent organization that launched vociferous attacks (without evidence) on allegedly “pro-Iranian” US journalists, the GEC inadvertently damaged the credibility of efforts to counter Iranian influence.1 A more effective approach would be to invest US resources in organizations that track and identify Iran’s digital influence networks without over-editorializing their findings.

The US Department of State should address regular press briefings to the Iranian people. Official US press briefings, addressed to the Iranian people, have traditionally been widely disseminated and received. By using such a megaphone, the United States could push back against Iran’s propaganda apparatus in a strong, cost-effective manner.

The US Agency for Global Media (USAGM) should not engage in overt pro-US influence operations. Iranians are savvy media consumers who have traditionally sought out diverse points of view. They are less inclined to embrace obvious pro-Western propaganda.

The Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) should independently attribute foreign influence operations. In January 2017, the ODNI attributed a significant foreign influence operation to Russia.2 In nearly three years since, dozens more disinformation campaigns have been publicly identified and attributed—but only by corporations like Facebook, Google, and Twitter. US intelligence services should work with social media companies to attribute future foreign influence operations.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) should create an appropriate intergovernmental entity to publicize foreign influence operations. Although the US intelligence services should work to defend the American people against foreign disinformation campaigns, they are not the entities that should publicize these operations on a regular basis. Instead, that job should fall to an organization modeled on the National Cyber Awareness System of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) and under the purview of DHS, which can communicate regular advisories across the US government and to the population at large.

In 2011, Iran’s former intelligence minister, Heidar Moslehi, remarked, “We do not have a physical war with the enemy, but we are engaged in heavy information [warfare].”3 At the time of Moslehi’s speech, Iran had just begun to seed the digital landscape with fabricated websites and social media personas. Today, it commands tens of thousands of them, waging an information war that shows no sign of ending.

Introduction

Social media has fundamentally transformed the nature of foreign influence activities. Today’s propagandists can cheaply and effectively influence the populations of distant nations, sharing micro-targeted content while masking their identities. Although this phenomenon came to the attention of many Western observers only after successful Russian interference in the 2016 US election, non-Western states have invested in digital influence capabilities for more than a decade. One pioneer is the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Modern Iran, born from Islamic revolution and engaged in a 41-year cold war with the United States, has been quick to study and exploit new communications technologies. This is the case even as it restricts use by its own citizens. Following the 2009 Green Movement—a series of pro-democracy protests, enabled by Twitter and other platforms, that threatened the stability of Iran’s theocratic government—Iranian propagandists vowed to use social media for their own ends.

By 2011, Iran claimed to have built “cyber battalions” that totaled more than eight thousand members trained in blogging, content production, and multimedia design.4 The same year, Iran was seeding Twitter with bots that it would use to steer international debate; it established the first of countless Facebook accounts that would share political content under false pretexts and fake identities.5 By 2015, Iran had expanded the scope of its digital influence efforts to include platforms like Reddit, where it sought to shape perceptions of the Syrian Civil War.6By 2018, Iran had developed sophisticated online personas that it used to launder propaganda through individual journalists and to even publish letters in regional US newspapers.7 By 2020, and following the US assassination of Iranian Major General Qasem Soleimani, Iran was using this apparatus to mount continuous influence operations against the United States.

Even as Western observers placed new emphasis on digital influence in the aftermath of the 2016 US election, they remained largely unaware of Iranian activities in the space. A number of suspicious Iranian tweets, identified by independent researchers, were initially misattributed to Russia. The first major identification of Iranian influence activities came in August 2018, published by the cybersecurity company FireEye.8 Facebook, Twitter, and Reddit followed with their own announcements, as they each dismantled pieces of the network. This was just the beginning. As of January 2020, Iranian influence activities have been the subject of seven additional takedown announcements by Facebook and Twitter, as well as numerous routine content-moderation actions. Only Russian activities have received more attention.

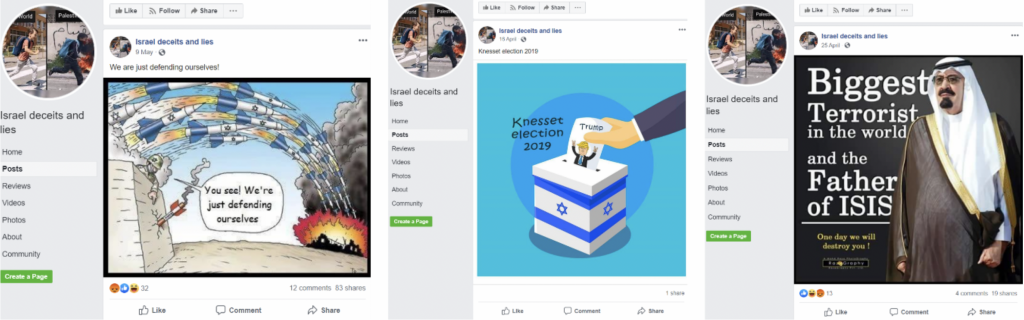

As focus on Iranian influence efforts has grown, however, so have misperceptions about the nature of these operations. There is a tendency to refer to these cumulative Iranian influence activities as “disinformation”: what the Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab) of the Atlantic Council defines as false or misleading information spread with the intention to deceive. The US Department of the Treasury has characterized all Iranian broadcasts as “disinformation.”9 For a time, the US Department of State funded the “Iran Disinformation Project,” the stated mission for which was to “bring to light disinformation emanating from the Islamic Republic of Iran.”10 There is a temptation among some US politicians to blame Iranian “disinformation” for a wide range of political obstacles—even including the anti-war movement within the United States.11 Iranian government proxies operated unattributed Facebook pages devoted to praise of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and condemnation of the Palestinian occupation. This particular network was removed in May 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

Iranian government proxies operated unattributed Facebook pages devoted to praise of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and condemnation of the Palestinian occupation. This particular network was removed in May 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

Iranian government proxies operated unattributed Facebook pages devoted to praise of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and condemnation of the Palestinian occupation. This particular network was removed in May 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

Iranian government proxies operated unattributed Facebook pages devoted to praise of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and condemnation of the Palestinian occupation. This particular network was removed in May 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

Although Iran has certainly engaged in the spread of falsehood, this does not represent the majority—or even a significant portion—of its known digital influence efforts. While Iran makes systematic use of inauthentic websites and social media personas, the actual content it disseminates is a mirror of its state propaganda: biased in Iran’s favor and contrary to US interests, but seldom wholly fabricated. If the principal intent of Russia’s digital influence efforts is to distract and dismay, Iran’s goal is most often to persuade. Where Russia uses clandestine means to play both sides of a political issue against each other, Iran uses clandestine means to amplify one side as loudly as possible. The goal is to build a guerrilla broadcasting apparatus that cannot be easily targeted by the United States or its allies.

This issue brief examines the history, development, and operation of Iran’s digital influence efforts, placing them in the broader context of Iranian security and foreign policy objectives. This work is based on a reading of literature regarding Iran’s conceptualizations of information warfare and international broadcasting, as well as all available analyses of Iran’s clandestine activities on social media platforms. It is supplemented by a review of the DFRLab’s archive of Iranian-operated Facebook pages.

Although this is the most comprehensive effort of its sort, the DFRLab could not directly translate all languages used in Iranian propaganda, nor can it be guaranteed that currently available open-source information provides a comprehensive view of Iranian influence efforts. This study, like all studies of social media manipulation, is subject to change as more facts emerge.

This brief begins with a discussion of the modern Iranian state’s approach to information and information control. It proceeds to a history of the Iranian Internet. Next, it examines the evolution of Iranian digital influence operations, followed by a discussion of the broader information conflict in which they take place. The brief concludes by considering the future nature and intent of Iran’s clandestine digital activities.

Double-edged sword: Information as both weapon and existential threat

The Islamic Republic of Iran came into being partly through the control and manipulation of information. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s sermons, smuggled into the country via audio cassettes and distributed widely, helped give birth to the Islamic Revolution. Following the establishment of a theocratic government in 1979, religious authorities used a mix of bombastic propaganda and brutal censorship to consolidate their political power and demonize potential opponents. Accordingly, information dominance represents a central focus of both foreign and domestic policy. Iran sees itself as engaged in a perennial information war: against Sunni Arab powers, against the forces of perceived Western neocolonialism, and particularly against the United States. Should the information conflict be lost, many Iranian officials believe the collapse of the state will soon follow.

Iran has conceived of itself as a beacon of Shia Islam since 1501, which saw the founding of a new Persian empire under the Safavid dynasty. The Safavid shahs embraced Shia Islam and used the resultant religious fervor to reunite old Persian provinces under their rule. Iran presented itself as an alternate leader of the Muslim world: one destined to clash sharply with the Sunni Islamic Ottoman and Abbasid caliphates to the west. At its peak, Iran controlled Baghdad, Bahrain, and western Afghanistan. Even as Iranian influence receded, as the leading Shia power, Iran’s rulers would continue to feel responsible for Shia minorities around the region. Iran would also continue a pattern of religious and ideological warfare against Saudi Arabia and other descendants of the Sunni caliphates.  Nineteenth-century portrayal of the 1514 Battle of Chaldiran, which marked a catastrophic defeat for the Safavids at the hands of the Ottoman Empire. The battle set the stage for centuries of imperial and religious conflict. Source: Agha Sadeq/Wikimedia

Nineteenth-century portrayal of the 1514 Battle of Chaldiran, which marked a catastrophic defeat for the Safavids at the hands of the Ottoman Empire. The battle set the stage for centuries of imperial and religious conflict. Source: Agha Sadeq/Wikimedia

Nineteenth-century portrayal of the 1514 Battle of Chaldiran, which marked a catastrophic defeat for the Safavids at the hands of the Ottoman Empire. The battle set the stage for centuries of imperial and religious conflict. Source: Agha Sadeq/Wikimedia

Nineteenth-century portrayal of the 1514 Battle of Chaldiran, which marked a catastrophic defeat for the Safavids at the hands of the Ottoman Empire. The battle set the stage for centuries of imperial and religious conflict. Source: Agha Sadeq/Wikimedia

Through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Iran prided and defined itself by its resistance to Western colonial adventures. That changed in 1953, at which time the United States and the United Kingdom overthrew Iran’s democratically elected government in order to reverse the nationalization of Iranian oil production. The shah of Iran, with support of the military and Western intelligence agencies, suspended constitutional protections and consolidated political power. For the next twenty-six years, opposition parties ceased to operate and the media was strictly controlled.

Only the religious establishment enjoyed relative freedom of speech and assembly. Its discontent culminated with the 1979 Islamic Revolution by the exiled preacher Ruhollah Khomeini.12 These revolutionaries framed their movement as a successful resistance to Western neocolonialism. Iran began to cultivate ties with other Islamic or anti-Western revolutionary movements—in Saudi Arabia, in Egypt, and (most successfully) in Lebanon, as well as farther afield in nations like Bolivia and Venezuela. Iran also came to despise Israel, which it saw as a Western imperial project.

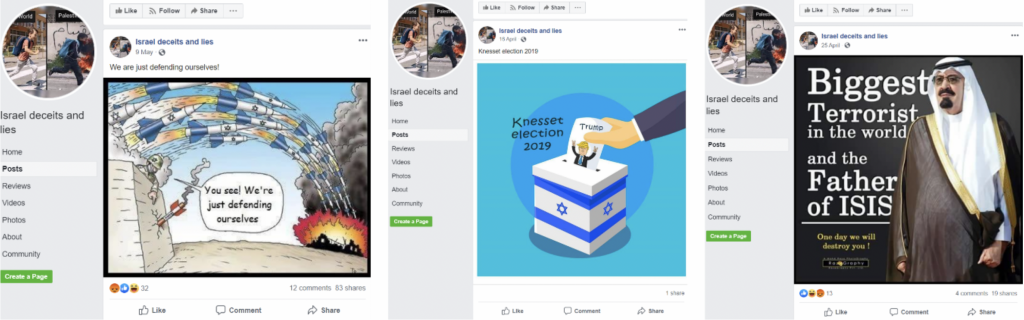

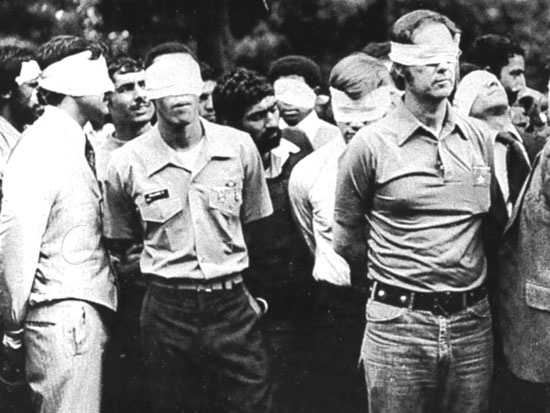

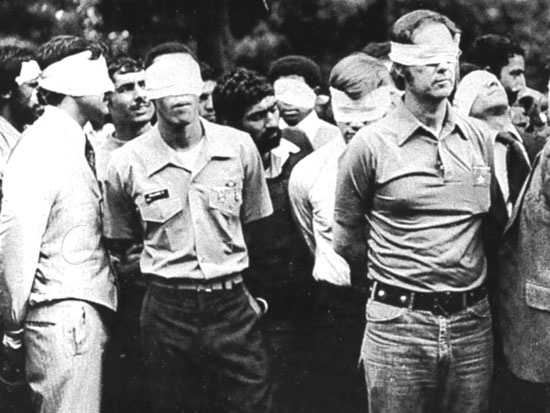

The 1979-81 hostage crisis, in which Iranian revolutionaries imprisoned fifty-two US diplomats and citizens at gunpoint, marked a decisive moment in both Iranian and US history. Images of blindfolded US officials, their hands tied behind their backs, were carried by television broadcasts around the world. For Iran, these images demonstrated the strength of the revolution. For the United States, they sowed anger and humiliation in a generation of policy makers.  Iranian government proxies operated Facebook pages intended to demean Israel and Saudi Arabia. This particular network was removed in October 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

Iranian government proxies operated Facebook pages intended to demean Israel and Saudi Arabia. This particular network was removed in October 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

Iranian government proxies operated Facebook pages intended to demean Israel and Saudi Arabia. This particular network was removed in October 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

Iranian government proxies operated Facebook pages intended to demean Israel and Saudi Arabia. This particular network was removed in October 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

Although US-Iranian relations waxed and waned in the decades following the 1979 revolution and subsequent hostage crisis, they entered steep decline in the early 2000s. Following the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Iran initially found itself on the same side of the United States against the Afghanistan Taliban, which had lent support to al-Qaeda and which had marginalized non-Pashtun ethnic groups. But as the United States prepared to invade Iraq, some voices within the George W. Bush Administration lobbied for a subsequent attack on Iran. This culminated in President Bush’s 2002 State of the Union address that named Iran to the “Axis of Evil” alongside Iraq and North Korea. The Iranian government, freshly remembering the devastating 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War, was shocked.

When the United States invaded Iraq in 2003, Iran maneuvered to ensure its agents of influence would be included in the Iraqi opposition that the United States would rely upon to form a new Iraqi government. As post-invasion US troop levels soared and US rhetoric grew more bellicose, Iran feared a prelude to direct attack. Accordingly, Iran provided arms and training to Shia militias fighting the US occupation, accounting for the deaths of at least six hundred US military personnel.13 Concurrently, the United States expanded economic sanctions and invested hundreds of millions of dollars to support Iranian dissidents and opposition groups.14

The diplomatic efforts under President Barack Obama that led to the negotiation of the 2015 Iran nuclear deal, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), saw a softening of rhetoric from both nations. Cyberattacks from Iran appeared to decrease when the JCPOA was in force.15

However, US-Iranian tensions increased sharply again under President Donald Trump, following his May 2018 decision to withdraw the United States from the JCPOA. Iran further dismissed new US sanctions, applied as part of a “maximum pressure” strategy, as tantamount to economic terrorism.16

With the US assassination of General Soleimani in January 2020 and Iranian military retaliation, the two countries have edged closer than ever to open military conflict. Blindfolded U.S. hostages and their Iranian captors outside the U.S. embassy in Tehran, Iran, 1979. US Army/Handout via REUTERS

Blindfolded U.S. hostages and their Iranian captors outside the U.S. embassy in Tehran, Iran, 1979. US Army/Handout via REUTERS

Blindfolded U.S. hostages and their Iranian captors outside the U.S. embassy in Tehran, Iran, 1979. US Army/Handout via REUTERS

Blindfolded U.S. hostages and their Iranian captors outside the U.S. embassy in Tehran, Iran, 1979. US Army/Handout via REUTERS

This US-Iran cold war has left many Iranian policymakers with a siege mentality in which the government lies under constant threat. One solution has been to invest heavily in a national narrative and share it with the world—to portray Iran as a religious beacon, as an anti-imperialist stalwart, and as a perennial underdog vis-à-vis the United States. In turn, this has necessitated that Iran maintain a strong propaganda apparatus for both domestic control and foreign influence. Doing so is not simply a “want,” but is considered integral to the state’s survival. US students protest in Washington DC during the 1979-81 Iran hostage crisis. Source: Marion Trikosko/Wikimedia

US students protest in Washington DC during the 1979-81 Iran hostage crisis. Source: Marion Trikosko/Wikimedia

US students protest in Washington DC during the 1979-81 Iran hostage crisis. Source: Marion Trikosko/Wikimedia

US students protest in Washington DC during the 1979-81 Iran hostage crisis. Source: Marion Trikosko/Wikimedia

Accordingly, state monopoly over television and radio broadcasting is mandated by Article 44 of the Iranian Constitution.17

The head of Iran’s state propaganda agency, Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB), is appointed by the theocratic supreme leader rather than Iran’s elected president or parliament.18

Despite growing economic turbulence and the mounting effects of US sanctions, the IRIB maintains an annual budget of approximately $750 million.19 This is roughly equivalent to the budget of the United States Agency for Global Media (USAGM, known as the Broadcasting Board of Governors until 2018).20 As a proportion of total government spending, however, Iran invests about fifty times as much in the IRIB as the United States does in the USAGM.21 The IRIB claims more than thirteen thousand employees in more than twenty countries.22 In 2013, the United States formally sanctioned the IRIB, citing its campaigns of censorship and distortion.23

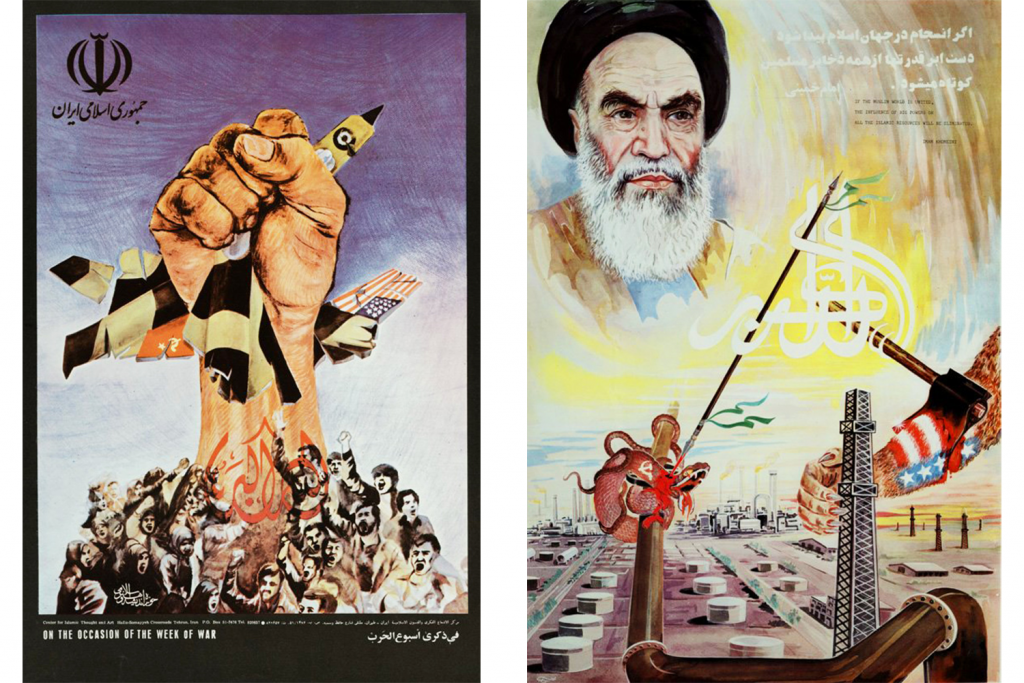

Within Iran, the IRIB operates twelve radio channels and forty-seven regional and national television channels; it also owns the Jam-e Jam newspaper, one of Iran’s largest print publications. Yet, the IRIB represents just one instrument of domestic influence. Other state institutions, like the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, administer their own newspapers and control the systems of funding and licensing that dictate the editorial positions of Iran’s quasi-independent press. The Office of the Supreme Leader runs another major newspaper and oversees a network of conservative publications that are answerable only to the religious authorities. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) has its own affiliated press operations, as does Iran’s major labor union, which itself exists under the government’s watchful eye.24 Although these news organizations offer competing views of the world, the spectrum of “acceptable” beliefs is dictated by state censors.  Iranian propaganda has long been suffused with a resistance to neocolonialism, evidenced by these 1980s posters. In the first (left), an Iranian fist crushes an Iraqi jet emblazoned with the flags of the United States and Soviet Union. In the second (right), radiant weapons attack embodiments of the United States and Soviet Union, which seek Iran’s natural resources. Source: University of Chicago Library

Iranian propaganda has long been suffused with a resistance to neocolonialism, evidenced by these 1980s posters. In the first (left), an Iranian fist crushes an Iraqi jet emblazoned with the flags of the United States and Soviet Union. In the second (right), radiant weapons attack embodiments of the United States and Soviet Union, which seek Iran’s natural resources. Source: University of Chicago Library

Iranian propaganda has long been suffused with a resistance to neocolonialism, evidenced by these 1980s posters. In the first (left), an Iranian fist crushes an Iraqi jet emblazoned with the flags of the United States and Soviet Union. In the second (right), radiant weapons attack embodiments of the United States and Soviet Union, which seek Iran’s natural resources. Source: University of Chicago Library

Iranian propaganda has long been suffused with a resistance to neocolonialism, evidenced by these 1980s posters. In the first (left), an Iranian fist crushes an Iraqi jet emblazoned with the flags of the United States and Soviet Union. In the second (right), radiant weapons attack embodiments of the United States and Soviet Union, which seek Iran’s natural resources. Source: University of Chicago Library

Internationally, the IRIB operates thirty radio channels and nine television networks.25 This scale of foreign broadcasting significantly increased following the US invasion of Iraq.26 Today, some of IRIB’s most prominent foreign-facing initiatives are: Al Alam, an Arabic-language station launched in 2003; PressTV, an English-language station launched in 2007; and Hispan TV, a Spanish-language station launched in 2011 and focused on Latin America. In 2016, the IRIB launched Pars Today, a consolidated news agency for IRIB’s international broadcasting efforts that offered programming in thirty-two languages.27 “Islamic Iran is facing a broad media war and the IRIB is at the forefront of this new war,” said the IRIB president of the venture.28

This conception of “media war” is owed to the international broadcasts that have long composed a significant part of Iran’s media environment. The oldest of these is Radio BBC, which began its Farsi programming in 1940 and exerted significant political and cultural influence over the Iranian elite, especially prior to the 1979 revolution.29 Other foreign radio stations include: Radio Zamaneh, based in the Netherlands; Deutsche Welle, based in Germany; Radio France Internationale; and Voice of Israel. With the advent of cheap satellite dishes in the mid-1990s, foreign television broadcasts became widely popular, despite a ban on home satellite use. The first targeted television broadcast was Voice of America-Persian News Network, launched in 1996. BBC Persian launched in 2009, drawing a regular audience of more than ten million. According to a 2010 survey by BBC Monitoring, 40 percent of Iranians were watching foreign satellite broadcasts.30

Since 9/11, and with an increasing military presence in the Middle East, the United States has sought to expand its Iran-focused broadcasting. In 2002, the then-Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG) launched Radio Farda, intended to strengthen its previous radio efforts.31 Throughout the 2000s, the BBG reduced or eliminated programs in other regions (notably Eastern Europe), while expanding funding for Iranian content.32 In 2006, the Bush Administration and the US Congress authorized the Iran Democracy Fund, which would allocate tens of millions of dollars to BBG broadcasts, as well as to Iranian opposition groups, many of which had media outlets of their own.33 Although this effort was softened under the Obama Administration, it has further escalated under the “maximum pressure” strategy of President Donald Trump. The fiscal year 2019 appropriations bill for the US Department of State expressly directed Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to consult with the USAGM to coordinate “counterinfluence programs” against Iran.34 A collage of IRIB-branded television channels and other media properties. Proportional to its national budget, Iran spends roughly fifty times as much as the United States on such broadcasting initiatives.

A collage of IRIB-branded television channels and other media properties. Proportional to its national budget, Iran spends roughly fifty times as much as the United States on such broadcasting initiatives.

A collage of IRIB-branded television channels and other media properties. Proportional to its national budget, Iran spends roughly fifty times as much as the United States on such broadcasting initiatives.

A collage of IRIB-branded television channels and other media properties. Proportional to its national budget, Iran spends roughly fifty times as much as the United States on such broadcasting initiatives.

These foreign broadcasting efforts are perceived as a grave threat by the Iranian government. Since the mid-2000s and the “color revolutions” that swept Georgia, Ukraine, and Lebanon, IRGC indoctrination has instilled fear within Iran of a similar revolution fomented by a US-led coalition.35 With the 2009 Green Movement and the amplification of pro-democracy activists by Western media, Iranian officials saw their worst fears realized. They called it “soft war.”36 The Islamic Development Organization, a supervisory religious and cultural body created by the supreme leader shortly after the 1979 revolution, described the conduct of soft war as follows:

[E]conomic malady, creation of discontent in the society, establishment of non-governmental organizations, war of media, and psychological operation in order to show government as a weak state…The elements of subversion use the present arenas in the society in order to reach their purposes; also, they try to create discord among the public opinion.”37

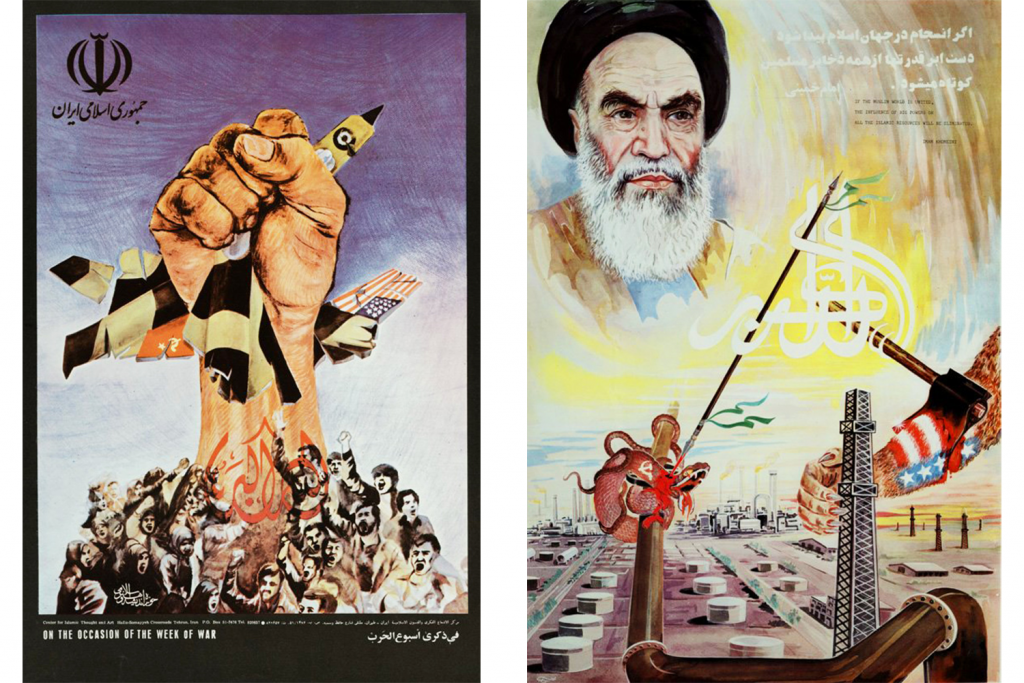

Countering soft war became an all-consuming task. In 2010, Iran labeled sixty media and international organizations as “soft war agents,” prohibiting their operations within the country.38 The Iranian Ministry of Defense authorized a dedicated soft-war military force, devoted to cultural preservation and psychological operations, in which even Iranian elementary schools were conceived as potential battlefields.39 In 2015, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei warned an assembled group of IRGC commanders that “economic and security infiltration” was less a threat than “intellectual, cultural, and political infiltration.”40 The control and manipulation of information was inextricably linked to national security.  This cartoon portrays an Iranian citizen protesting Iran’s presence in Gaza and Lebanon. Although he holds an Iranian flag, he has been radicalized by the Voice of America, BBC, and Gulf state media and is secretly controlled by Israel. The cartoon was shared by an unlabeled Iranian propaganda network on Instagram, removed in March 2019. Source: Facebook/Instagram

This cartoon portrays an Iranian citizen protesting Iran’s presence in Gaza and Lebanon. Although he holds an Iranian flag, he has been radicalized by the Voice of America, BBC, and Gulf state media and is secretly controlled by Israel. The cartoon was shared by an unlabeled Iranian propaganda network on Instagram, removed in March 2019. Source: Facebook/Instagram

This cartoon portrays an Iranian citizen protesting Iran’s presence in Gaza and Lebanon. Although he holds an Iranian flag, he has been radicalized by the Voice of America, BBC, and Gulf state media and is secretly controlled by Israel. The cartoon was shared by an unlabeled Iranian propaganda network on Instagram, removed in March 2019. Source: Facebook/Instagram

This cartoon portrays an Iranian citizen protesting Iran’s presence in Gaza and Lebanon. Although he holds an Iranian flag, he has been radicalized by the Voice of America, BBC, and Gulf state media and is secretly controlled by Israel. The cartoon was shared by an unlabeled Iranian propaganda network on Instagram, removed in March 2019. Source: Facebook/Instagram

Accordingly, Iran’s conventional military and IRGC planning emphasize informational control for both defense and offense. Iranian strategists see a conflict in which Iran is continually on the defensive: against hostile US, British, and Saudi broadcasters; against Israeli and Iranian opposition lobbying in the United States; and against a global information environment from which Iran is largely excluded due to accumulating sanctions.

As Iranian policymakers sought new ways to defend against foreign influence and shift to the information offensive, their attention would inevitably turn to the Internet.

Iran and the internet

Iran embraced the Internet early and aggressively, recognizing it as a new medium by which the state could strengthen its hand at home and improve broadcasting overseas. Iran’s universities joined the global network in 1993, following behind only Israel as the second Middle East nation to embrace the digital age.41 Initially, the Iranian government did not impose any censorship restrictions. It was thought that a free, unfettered Internet would serve the dual purposes of advancing scientific research and spreading Islamic scripture.42 Gradually, however, Iran would impose severe limitations on digital communications. With time, the Iranian Internet would become increasingly paradoxical: a rich digital culture increasingly beset by religious authorities who seek to turn it to their own ends.

By the early 2000s, the Internet seemed poised to reshape Iranian society. Although the web offered a new platform to spread Islamic teachings, it also offered a refuge where forbidden ideas could be discussed freely. Many young Iranians took full advantage of the opportunity. In 2001, there were 1,500 Internet cafes in Tehran alone.43 Blogging became a popular pastime; after the creation of the first Farsi-language blog in 2001, tens of thousands would shortly follow.44 These politically engaged online communities joined with reform-minded politicians and clerics, creating a push for liberalization that touched most aspects of Iranian society.45 For a theocratic state ruled by deeply suspicious religious scholars, a conservative backlash was inevitable.

The first major act of digital censorship came in 2001, when Iranian courts asserted control over Internet service providers (ISPs) and subjected them to strict monitoring and censorship standards. This was an extension of a general suppression of opposition media that began in 2000.46 Following the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, censorship enforcement became stricter and Iranian authorities began the first widespread arrest and torture of dissident bloggers.47 Yet, the pattern of repression was still uneven. When the conservative Mahmoud Ahmadinejad ran for president in 2005, for example, he did so promising to roll back restrictions on digital speech. At voting booths in Tehran, Iranians talked excitedly of this modern candidate, in a suit as opposed to clerical garb, promising to open the window to a digital world from which they had been increasingly isolated.

As Iranian authorities were coming to see the Internet as a threat, foreign broadcasters saw new opportunity. BBCPersian.com, which launched in 2001, soon became the BBC’s most popular non-English website (it would be blocked by Iran in 2006, although many visitors would find ways to circumvent the ban).48 In 2003, the BBG created a free proxy service that enabled Iranians to continue to visit the websites of Radio Farda and Voice of America, despite mounting censorship efforts.49By the mid-2000s, the US government was investing significant resources in Iran-targeted websites and Internet programming, while young Iranians gravitated to new Western social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter.50 At the same time, the Iranian government increasingly identified the Internet as the vector through which the United States and its allies were most likely to wage their “soft war.”51

What remained of the free Iranian Internet was dealt a crippling blow in the aftermath of the 2009 Green Movement. Dozens of bloggers were arrested and detained indefinitely. Facebook and Twitter were blocked. That same year, the IRGC bought a controlling stake in the Telecommunication Company of Iran, the state’s principal ISP, bringing Iranian Internet users under tighter surveillance.52 In 2011, Iran created a “cyber police” unit, which quickly became infamous for detaining a thirty-five-year-old blogger and torturing him to death.53 In 2012, Iran announced a Supreme Council of Cyberspace, which placed Internet regulation more directly in the hands of religious—not secular—authorities.54 In recent years, Iran has sought ever more control of online spaces, following government consensus that the Internet has become an information battleground, a tool of soft war, to be harnessed by the state and rationed to the people.  Tens of thousands of Iranians took to the streets to protest irregularities in the 2009 Iranian presidential election. These protests soon became known as the “Green Movement.” In their aftermath, Iranian authorities began to infiltrate and co-opt the digital platforms used by democratic activists. Source: Milad Avazbeigi/Wikimedia

Tens of thousands of Iranians took to the streets to protest irregularities in the 2009 Iranian presidential election. These protests soon became known as the “Green Movement.” In their aftermath, Iranian authorities began to infiltrate and co-opt the digital platforms used by democratic activists. Source: Milad Avazbeigi/Wikimedia

Tens of thousands of Iranians took to the streets to protest irregularities in the 2009 Iranian presidential election. These protests soon became known as the “Green Movement.” In their aftermath, Iranian authorities began to infiltrate and co-opt the digital platforms used by democratic activists. Source: Milad Avazbeigi/Wikimedia

Tens of thousands of Iranians took to the streets to protest irregularities in the 2009 Iranian presidential election. These protests soon became known as the “Green Movement.” In their aftermath, Iranian authorities began to infiltrate and co-opt the digital platforms used by democratic activists. Source: Milad Avazbeigi/Wikimedia

More sophisticated surveillance, coupled with regular arrest and imprisonment for “propaganda against the state,” has strangled Iran’s independent journalistic community, even under the watch of the ostensibly moderate President Hassan Rouhani.55 The government has also begun to crowdsource censorship to thousands of volunteers, who report speech violations to judicial authorities.56 All the while, Iran continues its slow work on the so-called “National Internet Project,” initiated in 2011, which envisions the creation of a wholly separate Internet.57 This “halal” digital ecosystem, free from foreign websites and influence, would allow complete awareness of all Internet traffic in the country—and total control over user data and speech. In May 2019, Iran announced that this system was 80 percent complete, although many questions remain regarding the effectiveness and feasibility of its implementation.58

The most significant test of Iran’s new Internet controls came in November 2019, when the government raised fuel prices by 50 percent overnight, sparking widely attended protests in at least one hundred cities.59 Iranian censors sprang into action, eliminating Internet access in the country for ninety hours—and slowing it to a crawl for days thereafter.60 By measure of scale and effectiveness, it was the largest Internet shutdown in history.61 Over that period, police and security officials responded with violence, killing as many as 1,500 unarmed protestors over the course of a month.62 Despite the staggering death toll, however, the communications blackout effectively starved the protestors of contemporaneous international support.

Mr. @realDonaldTrump In my opinion everyone especially a President should love all,and not differentiate between them. I love @KingJames #MichaelJordan @RaufMahmoud and all athletes, and wish them all the best.

In recent years, both Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and former Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad have launched popular English-language Twitter feeds in a bid to communicate with the wider digital public. This occurs even as Twitter remains forbidden to the Iranian people. Source: Twitter

Yet, even with these tightening government controls, some fifty-six million Iranians—70 percent of the population—are now regular Internet users.63 Many banned services, like Facebook, still enjoy widespread domestic popularity, thanks to the evasion of Internet filters and toleration by some state enforcers (in 2017, there were still as many as forty million Iranian Facebook users).64 Today, the locus of Iranian digital life is the fashion-friendly Instagram (at least twenty-four million users) and the encrypted Telegram (at least forty million users, despite a limited ban).65 Yet, as the Iranian people have found new online refuges, authorities follow close behind. On Instagram, state-aligned trolls harass and threaten users, particularly women, who are perceived to act in an “un-Islamic” fashion.66 On Telegram, the administrators of popular discussion groups have been regularly summoned by the IRGC, which reminds them that they are being watched.67

Congratulations to the @Raptors on winning the #NBAFinals @kawhileonaed on becoming #MVP and to the city of #Toronto. By having a strong work ethic you were able to show all athletes how to win. If I were president, I would definitely invite you all to Iran.

Ironically, as Iran has curtailed Internet freedom for its own citizens, the state has greatly expanded its use of social media platforms for diplomacy and propaganda abroad. These public-facing activities have been most prominent on Twitter. In 2013, President Rouhani famously shared his desire for rapprochement with the United States via his English-language Twitter account.68 Soon thereafter, Ayatollah Khamenei—who had registered a Twitter account shortly after the 2009 Green Revolution—also began to regularly tweet in English, commenting on issues like the 2014 Black Lives Matter protests in Ferguson, Missouri.69 Even former President Ahmadinejad, who himself oversaw the banning of Twitter in 2009, joined the platform in 2018 to build his foreign following. His seemingly innocuous sports commentary briefly made him a US social media celebrity.70

Yet, the increasing Twitter activity of Iranian politicians represents just the most visible piece of a much broader digital influence campaign.71 In the last five years, the major foreign broadcasting initiatives of the IRIB—Al Alam, PressTV, Hispan TV, and Pars Today—have all established significant web presences. At the same time, Iran has seeded a vast network of social media sockpuppets and fabricated websites, forging a new kind of propaganda apparatus in the process.

Iran’s digital influence efforts

Iran operates an immense web of online personas and propaganda mills, virtually none of which disclose their affiliation with the Iranian government. The first major attribution of Iran’s foreign influence efforts was made in August 2018 by the cybersecurity company FireEye.72 In the eighteen months since, disclosures by social media platforms and journalists have shed light on operations that began as early as 2008. These operations have targeted dozens of nations with tens of millions of pieces of content, varying widely in their message and intent. By studying these known influence campaigns in aggregate, one can infer much about the diverse actors that spread propaganda on behalf of the Iranian government, as well as the different objectives that Iran intends to accomplish by targeting its efforts across so many nations and regions.

First, it is useful to review the social media assets that have been definitively attributed to Iran. As of January 2020, Facebook has publicly identified: 766 pages followed by 5.4 million users; fifty-five groups joined by 143,000 users; 1,114 Facebook accounts; and 344 Instagram accounts followed by 439,000 users. Facebook has further attributed forty-three Facebook events and $57,000 in advertising to Iranian actors. Twitter has identified 7,896 accounts responsible for approximately 8.5 million messages. Reddit has identified forty-three accounts. There can be no guarantee that this represents the sum of Iranian efforts on these platforms.

Broadly, Iran’s foreign influence efforts evidence a level of routinization that distinguish it from Russia, China, Saudi Arabia, or any other nation that has built a digital influence apparatus. This is a result of the early integration of digital manipulation into Iranian government and military functions. In 2009, Ayatollah Khamenei stated that “content promotion” was “the most effective international weapon” against foreign adversaries.73 In 2011, the head of the IRIB bragged that he had developed seven cyber battalions of “media experts and specialists,” supposedly consisting of 8,400 members.74 Tehran’s IRGC headquarters has trained thousands of recruits in “content production,” teaching them social media strategy and graphic design.75 Given this heavy and longstanding emphasis, it is likely that many elements of the Iranian state—the IRIB, the office of the supreme leader, the intelligence services, the IRGC and associated militias, and the regular Iranian military—each employ their own Internet operatives.  Logos of the International Union of Digital Medium (IUVM), a cluster of ostensibly independent websites that aggressively repackaged and re-broadcast Iranian state media. The cluster operated, undetected, for five years before being identified in August 2018. Source: DFRLab/ivumnews.com

Logos of the International Union of Digital Medium (IUVM), a cluster of ostensibly independent websites that aggressively repackaged and re-broadcast Iranian state media. The cluster operated, undetected, for five years before being identified in August 2018. Source: DFRLab/ivumnews.com

Logos of the International Union of Digital Medium (IUVM), a cluster of ostensibly independent websites that aggressively repackaged and re-broadcast Iranian state media. The cluster operated, undetected, for five years before being identified in August 2018. Source: DFRLab/ivumnews.com

Logos of the International Union of Digital Medium (IUVM), a cluster of ostensibly independent websites that aggressively repackaged and re-broadcast Iranian state media. The cluster operated, undetected, for five years before being identified in August 2018. Source: DFRLab/ivumnews.com

Many Iranian influence efforts are intended to launder Iranian state media through seemingly unconnected sources. To this end, Iranian proxies operate a dizzying number of “independent” news outlets. These websites regularly copy the source material of Pars Today and other IRIB broadcasters, as well as official Iranian government press releases. In a bid for more content, they also plagiarize from wire services like Reuters and the Associated Press, as well as from Russian, Venezuelan, and Syrian state media.76 Dozens of such low-effort, high-output websites have been launched by Iranian proxies, beginning as early as 2012.77 In contrast to similarly structured commercial content mills, none of these websites feature advertising.

An example of this phenomenon can be seen in the International Union of Virtual Media (IUVM), a cluster of ostensibly independent news outlets that began operations in 2013 and continued until its discovery in 2018. The IUVM’s main website declared its intention “to become the largest virtual media network across the globe, in line with our steadfast determination to defend the oppressed peoples of the world.”78 It offered a line of associated properties: IUVMPress and IUVMTV, which functioned as news and video aggregators; IUVMApp, which offered “halal” smartphone games and Quranic education; and even IUVMPixel, which featured a range of anti-Saudi and anti-US comic strips. The IUVM also offered links to dozens of “member” websites, all of which were clearing houses for Iranian propaganda.79In a “digital flex,” Iranians spammed the Instagram account of Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in January 2019. Source: DFRLab/Instagram

In practice, the IUVM demonstrated the sheer size and complexity of Iran’s information-laundering apparatus. The IUVM regularly tweaked and republished official IRIB stories, only to have its articles republished, in turn, by other Iranian propaganda mills. In one case, the IUVM reproduced a message to pilgrims by Ayatollah Khamenei, taken from his personal website. The same day, a wholly different Iran-linked website (“britishleft.com”) reproduced the story and shared it with its own audience.80 In this fashion, a single piece of content could be passed from one website to the next, each with a different readership and editorial style.

A significant portion of Iran-attributed Twitter activity has sought to drive social media users to this underground propaganda network. In 2014, for instance, an Iranian botnet bombarded French journalists and commentators with twenty-three thousand links to a story that promised to reveal, “What they will never tell you about Christmas.”81 Other botnets turned the headlines of Iranian state media reports into seemingly original tweets: “U.S. has wiped Raqqah off the face of the earth” or “[ISIS]…Fails to Prevail over Syrian Army Positions in Eastern Deir Ezzur.”82

Although Iranians masqueraded as any number of different Twitter users—an unemployed French journalist, or a Venezuelan football commentator—they put little effort into establishing convincing identities or infiltrating the wider political dialogue. Instead, they relentlessly promoted their own material, willing to rapidly switch from one persona to another if it could improve their chances of engagement. In one case, an account that was called “Liberty Front Press” (named after an Iranian propaganda front) abruptly changed its username to “Berniecrats.” Even with the sudden identity switch, however, the account’s content remained the same.83

Sometimes, such Iranian spam tactics proudly broadcast their origin. In January 2019, following Secretary of State Pompeo’s announcement of a summit on Iran and Middle East security, his official Instagram page was bombarded by thousands of mostly identical anti-American comments, many garnished with Iranian flags.84 In January 2020, following the US assassination of General Soleimani, Iranian Instagram accounts tagged the White House and members of the Trump family with thousands of graphic, anti-American images and memes.85 Analyst Cindy Otis described this as a “digital flex,” intended to demonstrate the strength and volume of Iran’s digital communications apparatus.86

“Pars Today Hausa” shared content related to Sudanese politics, Nigeria’s All Progressive Congress, crises in Mozambique, and conflicts in the Central African Republic between armed groups and political leaders. It was removed in April 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

“Pars Today Hausa” shared content related to Sudanese politics, Nigeria’s All Progressive Congress, crises in Mozambique, and conflicts in the Central African Republic between armed groups and political leaders. It was removed in April 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

Atop this network of propaganda mills and Twitter boosters, Iranian proxies operate a vast network of content-focused Facebook and Instagram pages. Some of these seek to drive traffic to Iranian state media or associated websites; others act as standalone news outlets, laundering Iranian propaganda through yet another seemingly unconnected source. Through Facebook especially, Iran has built hundreds of region-specific pages that have reached millions of users in every corner of the world.

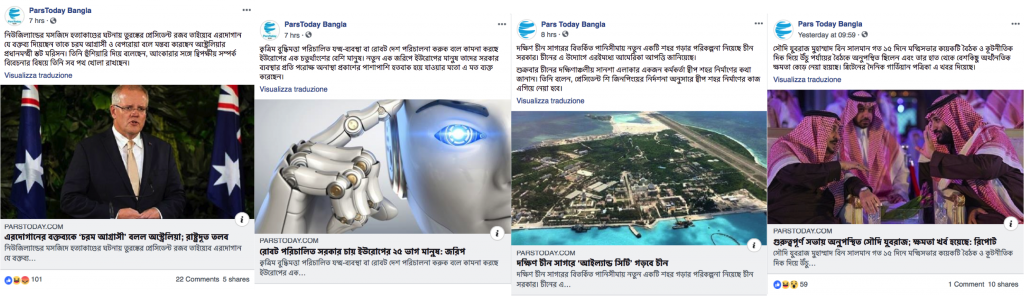

Some of these pages make little effort to disguise their identities. In March 2019, for instance, Facebook removed a network of pages with names like “Pars Today Hausa” (which translated Iranian broadcasts into Hausa) and “Pars Today Bangla” (which did the same for Bengali).87 This network targeted Facebook users in Nigeria, Bangladesh, India, and Kazakhstan. In case there was any doubt as to the operation’s origins, its administrators listed their location as Iran—and their employer as the IRIB.88 “Pars Today Bangla” shared content related to Turkish and Australian politicians, European wariness of artificial intelligence advancements, Chinese innovations, and Saudi Arabian leadership. It was removed in April 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

“Pars Today Bangla” shared content related to Turkish and Australian politicians, European wariness of artificial intelligence advancements, Chinese innovations, and Saudi Arabian leadership. It was removed in April 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

“Pars Today Bangla” shared content related to Turkish and Australian politicians, European wariness of artificial intelligence advancements, Chinese innovations, and Saudi Arabian leadership. It was removed in April 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

“Pars Today Bangla” shared content related to Turkish and Australian politicians, European wariness of artificial intelligence advancements, Chinese innovations, and Saudi Arabian leadership. It was removed in April 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

Other pages go to considerable lengths to cover their tracks. A massive Arabic and English-language influence network, removed by Facebook in January 2019, managed to operate since 2010 while offering few clues about its origins.89 Instead, the pages (with names like “Stop Killing Palestinian Children” and “Yemen Not Alone”) managed to blend into a broader community of anti-Israeli, anti-Saudi activists.90 Few Facebook users inclined to share the content of such pages would be disposed to check—or care—if the same content had been previously shared by Iranian state propagandists.

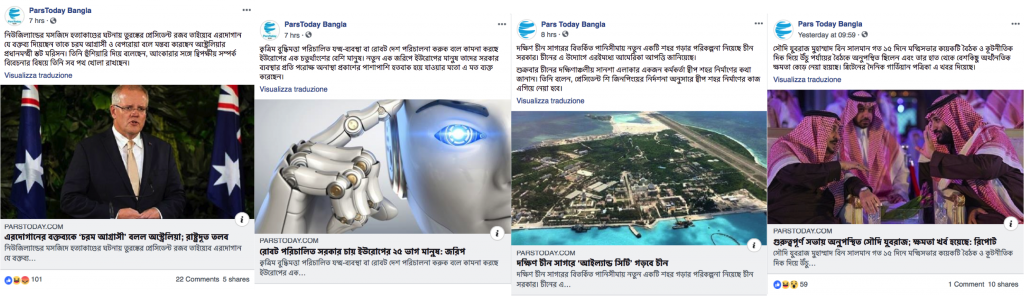

Recently, Iranian proxies have grown bolder in their attempts to undermine or co-opt foreign media outlets. Sometimes, it is as straightforward as a misleading domain name (“tel-avivtimes.com”), intended to disguise an offshoot propaganda website as a credible local news source.91 Other times, it involves a mix of plagiarism and creative misspellings, like appending the BBC logo to an Instagram page called “bbcgraphy,” or stealing the Radio Farda logo for an Instagram page called “radiofardaaaaaa.” One cleverly mislabeled Facebook page, “AlArabyi” (similar to the name of a major Saudi-funded broadcaster) accumulated five thousand followers while sharing ardently pro-Iranian material and claiming the real “AlArabiya.net” as its homepage.92 Comparison of an Iranian Facebook facsimile, @AlArabyi (top) with the verified version, @AlArabiya (bottom). Although the two pages appeared identical, they broadcast diametrically opposed messages. The Iranian lookalike was removed in May 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

Comparison of an Iranian Facebook facsimile, @AlArabyi (top) with the verified version, @AlArabiya (bottom). Although the two pages appeared identical, they broadcast diametrically opposed messages. The Iranian lookalike was removed in May 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

Comparison of an Iranian Facebook facsimile, @AlArabyi (top) with the verified version, @AlArabiya (bottom). Although the two pages appeared identical, they broadcast diametrically opposed messages. The Iranian lookalike was removed in May 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

Comparison of an Iranian Facebook facsimile, @AlArabyi (top) with the verified version, @AlArabiya (bottom). Although the two pages appeared identical, they broadcast diametrically opposed messages. The Iranian lookalike was removed in May 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

A tiny portion of Iranian influence activities demonstrate a level of sophistication that differs markedly from other efforts. These suggest the work of a military organization or intelligence agency rather than that of an IRIB civil servant or patriotic troll farm. In May 2019, Citizen Lab uncovered an advanced network of social media personas and look-alike websites that sought to target and launder content through individual Western journalists.93 These Iranian proxies showed familiarity with the major actors and influencers within the US Middle East policy community. They also proved adept at social engineering, often masquerading as young women and engaging in extended conversations to cultivate trust in their targets.

In one case, an Iranian sockpuppet pressured a US-based journalist to amplify a false story that claimed a former Israeli defense minister had been dismissed for being a Russian agent. The story was wrapped in a picture-perfect copy of the website of Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. The only indication was the domain name: “belfercenter.net” instead of “belfercenter.org.”94 All told, Citizen Lab counted one hundred and thirty-five articles, seventy-two domains, eleven social media personas, and one hundred and sixty persona-authored stories that composed the operation.95 This was testament to just how far Iran’s digital influence efforts have evolved in the past decade—and how they might develop in the years ahead.

Iran’s digital influence efforts in context

Iran has built a prolific online influence apparatus. Over time, the Iranian government has realigned its propaganda efforts to meet evolving foreign policy goals. It has also been forced to adapt by events beyond its control, often battling its own clumsiness along the way. By considering the general content and context of Iranian influence operations, it is possible to distinguish them from the disinformation campaigns of Russia and other US adversaries.

As a whole, Iran’s digital influence operations represent a continuation of public diplomacy, albeit conducted through misleading websites and social media sockpuppets. Iran invests significant energy injecting pro-Iranian content into the information environments of countries that offer little direct strategic utility. For instance, Iranian proxies have built numerous websites and Facebook pages targeting audiences in Indonesia, which boasts the largest Muslim population in the world.96 They have done the same for Nigeria, which has the largest Muslim population in Africa, and which includes a restive Shia minority.97 The primary aim of these efforts is to simply “tell Iran’s story,” the same as any Western government broadcaster might strive to do. The difference is that, as an international pariah, Iran must pursue this work through more clandestine means. Global observers have long learned to doubt the truthfulness and sincerity of Iranian-branded media.

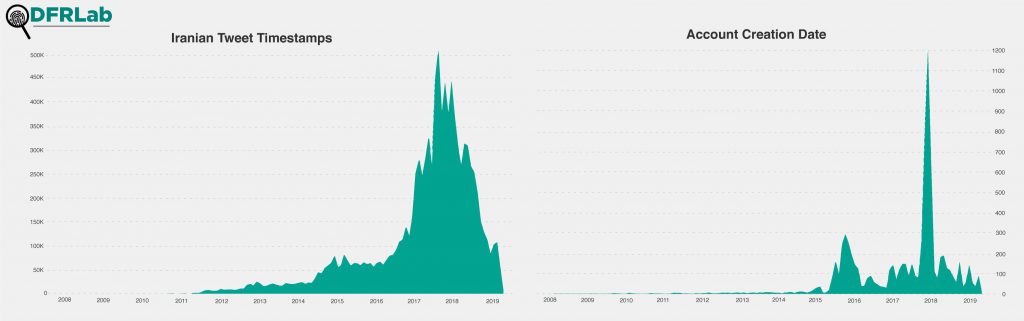

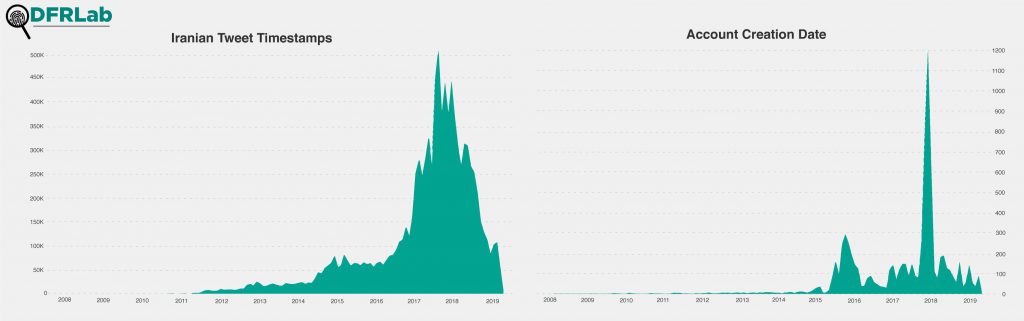

Where Iran turns this apparatus against the United States and its allies, it is often to achieve definable foreign policy objectives. In 2014, for example, Iran helped amplify a Lebanese conspiracy theory that the United States had created the self-declared Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS).98 The clear objective was to blunt US soft-power efforts in Lebanon and to strengthen the relative position of the Iranian-backed Hezbollah, which was engaged in its own propaganda battle. Iran exhibits similar behavior in its routine amplification of Palestinian civilian deaths at the hands of the Israeli Defense Forces, the killing of Yemeni civilians by the Saudi-led coalition, or its focus on the toll of US air strikes in Iraq and Syria. Each is intended to diminish the image of US-aligned powers, while masking Iran’s role in these and other proxy conflicts.  Graph of the timestamps and account creation dates of roughly 8.5 million tweets by 8,000 Iranian government-linked accounts, operating between 2008 and 2019. Note activity spikes during mid-2015 and mid-2018. These correspond with the US accession to and subsequent withdrawal from the JCPOA. Source: Kanishk Karan/DFRLab

Graph of the timestamps and account creation dates of roughly 8.5 million tweets by 8,000 Iranian government-linked accounts, operating between 2008 and 2019. Note activity spikes during mid-2015 and mid-2018. These correspond with the US accession to and subsequent withdrawal from the JCPOA. Source: Kanishk Karan/DFRLab

Graph of the timestamps and account creation dates of roughly 8.5 million tweets by 8,000 Iranian government-linked accounts, operating between 2008 and 2019. Note activity spikes during mid-2015 and mid-2018. These correspond with the US accession to and subsequent withdrawal from the JCPOA. Source: Kanishk Karan/DFRLab

Graph of the timestamps and account creation dates of roughly 8.5 million tweets by 8,000 Iranian government-linked accounts, operating between 2008 and 2019. Note activity spikes during mid-2015 and mid-2018. These correspond with the US accession to and subsequent withdrawal from the JCPOA. Source: Kanishk Karan/DFRLab

More broadly, it is no coincidence that Iranian-attributed Twitter activity saw its most significant spikes in mid-2015 and mid-2018. The first spike aligned with the contentious US domestic debate regarding adoption of the JCPOA, which set limits on Iranian nuclear development; the second aligned with the unilateral US withdrawal from that same agreement. For Iran, this digital influence apparatus represents a natural and potent tool to achieve its geopolitical ends.

Critically, Iran has so far demonstrated little interest in directly affecting US elections. In 2016, Iranian proxies briefly operated a Facebook page that sought to boost the candidacy of Senator Bernie Sanders (D-VT) in the Democratic presidential primary. The effort gained little engagement, however, and lasted only a month before going dormant.99 It appears that this was an experiment by Iranian propagandists, who subsequently abandoned it for other influence efforts less focused on direct foreign electioneering. More recently, Iranian proxies have sought to compromise email accounts linked to the Trump re-election campaign, although the objectives and extent of this effort remain unknown.100 “Free Iran” was one of several anti-Iranian Facebook pages, ostensibly operated by Iranian democratic activists. In reality, it was administered by Saudi government proxies and was part of a large influence network removed in August 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

“Free Iran” was one of several anti-Iranian Facebook pages, ostensibly operated by Iranian democratic activists. In reality, it was administered by Saudi government proxies and was part of a large influence network removed in August 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

“Free Iran” was one of several anti-Iranian Facebook pages, ostensibly operated by Iranian democratic activists. In reality, it was administered by Saudi government proxies and was part of a large influence network removed in August 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

“Free Iran” was one of several anti-Iranian Facebook pages, ostensibly operated by Iranian democratic activists. In reality, it was administered by Saudi government proxies and was part of a large influence network removed in August 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

Instead, Iranian interference in US politics has almost exclusively taken the form of websites, Facebook pages, and Twitter accounts that seek to redirect left-leaning causes to their own ends. An example can be seen in “BLMNews.com,” a relatively popular US outlet identified as an Iranian asset by Facebook in October 2019, which used the language and iconography of the Black Lives Matter movement to launder Iranian state propaganda to progressive activists.101 The expected stories about US race relations were intermingled with a surprisingly heavy focus on US sanctions policy and the humanitarian work of Lebanon’s Hezbollah. When Iranian propagandists produce material that glorifies particular Western politicians or social movements, it is almost exclusively in the context of advancing a clear Iranian foreign policy objective.

In this way, Iran’s approach to digital influence operations differs sharply from that of Russia. Where Russian sockpuppets may infiltrate either side of a political debate—and often both sides at once—Iranian proxies are fairly consistent in their positions. Where Russia routinely disseminates false stories with the aim of polluting the information environment, Iran makes less use of obvious disinformation (although its messaging is still obviously biased). Where the Russian approach is essentially nihilistic, intended to erode the very nature of “truth,” Iran advances a distorted truth that exaggerates Iran’s moral authority, while minimizing Iran’s repression of its citizens and the steep human cost of its own imperial adventures in the wider Middle East.

Yet, for all the investment that Iran has made in digital influence, it is still the underdog in the broader information struggle. As Iran has developed its social media manipulation capabilities, so have committed Iranian adversaries like Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Israel.102 In August 2019, for instance, Facebook identified a series of Saudi propaganda assets that sought to undermine Iran’s reputation. With names like “Free Iran,” the pages shared glitzy infographics that highlighted Iran’s high levels of drug addiction or its historic massacre of political prisoners.

This digital landscape is further complicated by the presence of Iranian opposition groups, which have invested heavily in influence capabilities of their own.103 In particular, the Mojahedin-e Khalq (MEK), an exiled Islamo-socialist militant organization, has purportedly built an “online social media factory” in its 2,500-member-strong Albanian compound.104 A DFRLab analysis of popular anti-Iran Twitter hashtags—#IslamicRegimeMustGo or #IRGCTerrorists—found significant evidence of inauthentic coordination and amplification.105 Such hashtag campaigns have been used to lobby US officials for direct military action against Iran.

At the same time, the United States has sought to box Iran out of as much of the global media environment as possible. In November 2018, the US Department of the Treasury fully re-imposed sanctions on seven hundred Iranian entities and individuals, including the entirety of the IRIB.106 In April 2019, the United States took the unprecedented step of designating the IRGC as a Foreign Terrorist Organization, severely restricting its international activities.107 In January 2020, Facebook cited this US designation as justification for removing content by Iranian users that “commended” the IRGC or deceased Major General Soleimani.108 Stories shared by “BLM News” focused disproportionately on Israel, Lebanon, Yemen, and US sanctions policy. The website was revealed to be an Iranian propaganda front and its assets removed in October 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

Stories shared by “BLM News” focused disproportionately on Israel, Lebanon, Yemen, and US sanctions policy. The website was revealed to be an Iranian propaganda front and its assets removed in October 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

Stories shared by “BLM News” focused disproportionately on Israel, Lebanon, Yemen, and US sanctions policy. The website was revealed to be an Iranian propaganda front and its assets removed in October 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

Stories shared by “BLM News” focused disproportionately on Israel, Lebanon, Yemen, and US sanctions policy. The website was revealed to be an Iranian propaganda front and its assets removed in October 2019. Source: DFRLab/Facebook

By necessity, therefore, Iran has turned increasingly to clandestine digital influence activities as its public-facing broadcasts face more challenges in reaching an audience. The result is a new kind of guerrilla broadcasting, calibrated for the social media age.

Conclusions and recommendations

Iran’s digital influence operations are best understood as a form of public diplomacy under duress. Because the IRIB has been sanctioned and the IRGC classified as a terrorist group, Iranian messaging is most effective if it appears to come from a neutral third party. But, whereas Russia’s ongoing disinformation campaigns are intended to obfuscate truth and discredit Western institutions, Iran’s efforts exemplify the art of indirect “Persian persuasion” and deflection. Iran seeks to elevate itself as an alternate leader of the Muslim world, while presenting itself as a bulwark against the perceived forces of neocolonialism and US interventionism. It seeks to do so through a messaging apparatus that its adversaries cannot easily inhibit or destroy.

As the United States considers policies to safeguard its elections and confront Iranian influence activities, three conclusions can be drawn about the nature of Iran’s modern propaganda apparatus.

Iran’s digital influence efforts involve centralized goals and disparate agents. Ayatollah Khamenei himself has emphasized the importance of digital influence operations to Iran’s survival. Accordingly, the government has invested heavily in such capabilities. Yet, different elements of Iran’s digital propaganda apparatus evidence the involvement of different agencies, from the mass dissemination of IRIB content (likely conducted by the IRIB itself) to the targeting of individual Western journalists (likely conducted by the IRGC). It is not clear how, or if, these agencies coordinate their operations.

These goals are closely tied to Iran’s geopolitical interests. Nearly all content spread by Iran’s digital influence efforts relates directly to its worldview or specific foreign policy objectives. Consequently, it is easier to identify the operations of Iran than those of other actors like Russia, whose content is more likely to be politically agnostic. With regard to the United States, these goals are clear. The first goal is the elimination of US military presence in the Middle East. The second goal, at least until Soleimani’s January 2020 killing, has been preservation of the JCPOA and ensuring that the US returns to compliance with the agreement.

Iran may attempt direct electoral interference in 2020 and beyond. To date, there is little evidence that Iran has sought to affect the outcome of a US election. This does not, however, preclude future such campaigns. Iran is certainly aware of Russia’s successful interference in the 2016 US election and how a small investiture of resources had such an outsize impact on US political discourse. If a determination is made that Iran’s foreign policy goals can be better achieved by President Trump’s electoral defeat, Iranian proxies are likely to mount efforts to that end.

Additionally, five steps can be taken to better prepare the United States to meet this threat.

The US Global Engagement Center (GEC) should invest resources in identifying and neutralizing—but not editorializing about—Iran’s digital influence networks. Through its funding of the Iran Disinformation Project, an independent organization that launched vociferous attacks (without evidence) on allegedly “pro-Iranian” US journalists, the GEC inadvertently damaged the credibility of US efforts to counter Iranian influence.109 A more effective approach will be to invest US resources in organizations that track and identify Iran’s digital influence networks without over-editorializing their findings. Basic technological innovations, like automated search and text-matching of Iranian state propaganda products, could greatly assist in this effort. In order to maintain the credibility of their findings, the organizations that unspool these networks should be as objective and transparent as possible in their work. To this end, the GEC should avoid contracting longstanding Iranian opposition groups for such efforts.

The US Department of State should address regular press briefings to the Iranian people. Official US press briefings addressed to the Iranian people have traditionally been widely disseminated and received. By using such a megaphone, the United States could push back against Iran’s propaganda apparatus in a strong, cost-effective manner. The one-sided claims and attacks by Iran’s digital influence apparatus work best when they go unanswered. Currently, most of them do.

The US Agency for Global Media (USAGM) should not engage in overt pro-US influence operations. Iranians are savvy media consumers who have traditionally sought out diverse points of view—something that explains the enduring popularity of BBC Persian in the country. They are less inclined to embrace obvious pro-Western propaganda. By tasking USAGM with “counterinfluence programs” against Iran in the fiscal year 2019 appropriations bill for the Department of State, Congress endangers both the editorial independence and effectiveness of the USAGM. An ostensibly independent media broadcaster is not the appropriate entity to conduct such programs.

The Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) should independently attribute foreign influence operations. In January 2017, the ODNI attributed a significant foreign influence operation to Russia.110 In nearly three years since, dozens more disinformation campaigns have been publicly identified and attributed—but only by corporations like Facebook, Google, and Twitter. It is inappropriate that such politically consequential work be conducted entirely by private enterprise. US intelligence services should work with social media companies to attribute future foreign influence operations. This is relevant against state actors like Iran. It is also relevant against organized non-state entities like the MEK, which habitually target the American people, but which have received comparatively little intelligence focus.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) should create an appropriate intergovernmental entity to publicize foreign influence operations. Although the US intelligence services should work to defend the American people against foreign disinformation campaigns, they are not the entities that should publicize these operations on a regular basis. Instead, that job should fall to an organization modeled on the National Cyber Awareness System of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) and under the purview of DHS, which can communicate regular advisories across US government and to the population at large. A similar nonpartisan organization already exists in the Critical Election Incident Public Protocol of the Canadian government.111

In 2011, former Iranian Intelligence Minister Heidar Moslehi remarked that, “We do not have a physical war with the enemy, but we are engaged in heavy information [warfare].”112 At the time of Moslehi’s speech, Iran had just begun to seed the digital landscape with fabricated websites and social media personas. Today, it commands tens of thousands of them, waging an information war that shows no sign of ending.

No comments:

Post a Comment