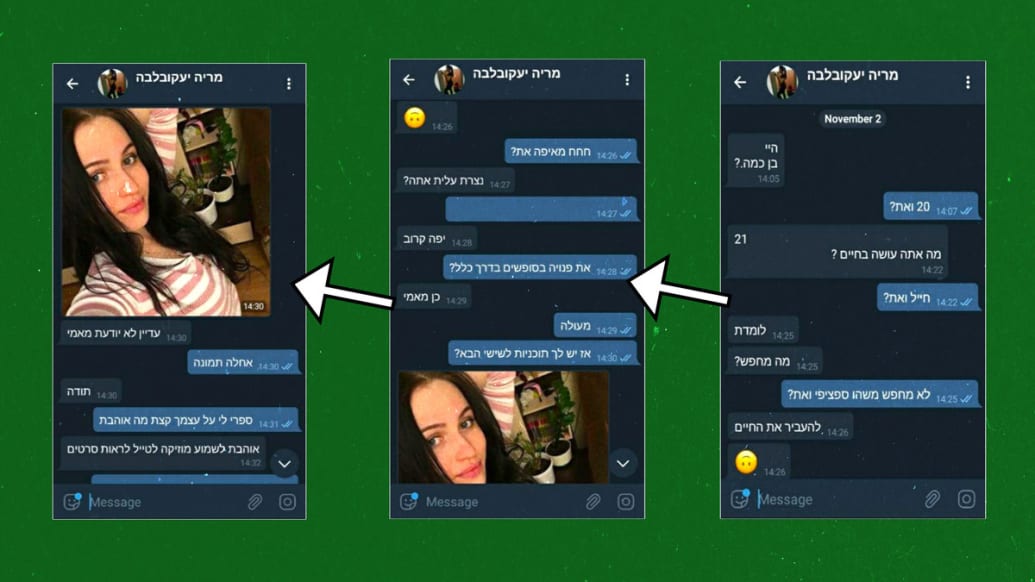

TEL AVIV—The 20-year-old Israeli soldier couldn’t believe his luck. Out of nowhere, a pretty brunette named Maria Yakovlevah messaged him on Telegram. She was a year older, originally from Odessa, but now living in northern Israel according to her Facebook profile, which had a post that read, in Hebrew: “A pretty woman isn’t always happy, but a happy woman is always pretty.”

The two got to chatting. Maria said she loved listening to music, traveling and watching movies. "What are you looking for?" the soldier inquired. “To go through life,” Maria replied with a coquettish upside-down smiley face emoji. The conversation turned more flirtatious; Maria pressed the soldier to download an app called “catchandsee” so they could exchange risqué pictures—which he did, or at least tried to.

As the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) revealed last week, “Maria Yakovlevah” wasn’t a real person, but rather an elaborate online cutout created by Hamas, the Palestinian Islamist group. And the link she sent for the “catchandsee” app, which was supposed to work like the popular Snapchat and erase all those racy images? Once clicked, it inserted powerful spyware into the soldier’s smartphone, allowing Hamas to take full control of the device—camera and GPS locator, contacts, files, images, and audio—and send all the data back to Hamas’ servers.

“According to the IDF, hundreds of soldiers were targeted.”

Honey traps have been laid for Israeli soldiers in many ways over many years, but in the past the aim was to lure the man into a vulnerable position. Now the target, pretty much from start to finish, is his phone.

According to the IDF, hundreds of soldiers were targeted, with “several dozen” non-officers potentially compromised. The Israeli military was at pains to stress that no classified information was leaked, yet in its scale and sophistication, even IDF spokesman Lt. Col. Jonathan Conricus admitted that Hamas’ cyber-unit was “upping its game."

Multiple fake online personas of attractive younger women with Israeli names, all writing in passable, slang-infused Hebrew, operating credible looking profiles across Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, and the aforementioned Telegram.

To throw suspicious targets further off the scent, the images used were slightly altered to make it harder to reverse-search for them online. To explain away certain language mistakes, the characters created often were portrayed as recent immigrants (like Maria), with some even claiming to be deaf or speech-impaired to keep the conversations text only. Yet female Hamas operatives on several occasions did respond with brief audio messages—again, in Hebrew.

The IDF, famously, is a conscript army with mandatory service beginning at 18; despite its reputation for dominance, the people on the ground are often teenagers, as preoccupied with games and memes, boys and girls, as their peers elsewhere. Smartphones are a constant presence on bases, used to while away the hours on guard duty, keep in touch with family, and set up romantic encounters. Through its cyber capabilities and elaborate social engineering, Hamas has attempted to exploit this all-too “human” breach to gather operational intelligence on the IDF.

“This time, their weapon isn’t a bomb, gun, or vehicle. It’s a simple friend request.”

— IDF spokesman on Hamas' use of social media in 2017

Despite the incongruity of pious Islamist militants pretending to be young women who throw around words like “honey” and “sweetheart,” Hamas operatives above all are innovators. In the organization's three-decade conflict with Israel, the group perfected the suicide bomb vest in the 1990s to bloody effect; turned rocket fire from its Gaza Strip stronghold into a normal occurrence (and was indeed the first since Saddam Hussein to shell Tel Aviv in 2012); and has developed extensive cross-border tunnel networks that would have been the envy of the Vietcong.

The latest creative dimension, apparently, is cyber—as a terror group that controls a slender, overcrowded piece of territory with an average of 11 hours of electricity a day does battle with the vaunted “Start-Up Nation.”

Arguably the first reported instance of a Palestinian cyber attack against Israel came in 2002. IDF reconnaissance drones flying high above Gaza were hacked by Palestinian Authority security officers, with the intercepted footage relayed to Hamas. “We shouldn’t underestimate them,” veteran Palestinian affairs correspondent Avi Issacharoff, who first reported the story a few years ago, told The Daily Beast. “The Palestinians, just like every enemy in every locale, are getting better in each level, and part of that is technology.”

“Young women targeted gullible Israeli soldiers and pressed them to install what was in fact a virus.”

In 2014, according to Israeli security sources, Hamas itself was able to beam its own television footage via terrestrial antenna into the homes of Bedouin Arabs in southern Israel during that summer’s Gaza war. Beginning around this time, actual cyber attacks on Israeli websites—usually simple denial of service (DoS) campaigns—became more common, although it’s unclear if these were Hamas orchestrated.

In early 2017, however, the IDF publicized for the first time Hamas efforts to use fake Facebook profiles of attractive younger women to gather information on soldiers and entice them to download a video chatting app that, similar to the recent campaign, was really spyware meant to take control of the smartphone. “This time, their weapon isn’t a bomb, gun, or vehicle. It’s a simple friend request,” the IDF said in reference to Hamas.

The following year Hamas’s cyber unit doubled down, launching two fake dating apps—called Glance Love and Wink Chat—that were openly available for download in the Google Play store.

Here again, young women targeted gullible Israeli soldiers and pressed them to install what was in fact a virus. By the IDF’s own count, hundreds of Israelis, including soldiers serving in frontline bases near the Israel-Gaza border, were targeted, and a dozen at least actually downloaded the apps. In a literary flourish, the IDF termed the campaign “Operation Broken Heart.”

The summer of 2018 also saw Hamas launch two standalone apps geared to an Israeli audience. The first was for real-time soccer updates from the ongoing World Cup; the second, ironically, was a rocket alert app meant to warn Israelis of incoming fire from Gaza. Both operated similarly to the other fake apps as “Trojan Horses” to implant spyware and take control of smartphones. A separate jogging app also reportedly was utilized by Hamas attackers to identify the phone numbers of Israeli soldiers serving near the Gaza frontier, allowing the group to bombard them with malware phishing requests.

“Hamas views young (male) IDF conscripts as the soft underbelly of the IDF’s defenses.”

To be sure, Israel hasn’t been Hamas’ only cyber target. For the last few years, Hamas’s (now) bitter rivals in the Palestinian Authority and Fatah party, who control the West Bank, also have fallen prey. In one case Fatah’s homepage was hacked, with the attackers embedding a “mirrored” link for the party’s app that downloaded the spyware (again allowing remote control over the entire phone).

Other phishing attacks targeting Palestinian Authority officials via email used official-looking Word documents as the entry vehicle for the malware. Earlier this year, an Israeli cybersecurity firm revealed new attacks against the PA—likely perpetrated by Hamas—that used email attachments purportedly relating to current events (the death of Qassem Soleimani, Jared Kushner) as the bait.

“I’m not going to say [these campaigns] are not powerful or weak,” Lt. Col. A, a senior officer in the IDF’s Cyber Directorate, told The Daily Beast as this phenomenon was developing in recent years. “They are interesting.”

The IDF maintains that the tangible damage in all these cases was limited and that the speed with which the attacks were identified and stopped shows the strength of Israel’s own capabilities. Moreover, both IDF and private cyber experts stress that Hamas’s cyber unit is nowhere near the level of state actors like, say, Iran, Russia or China.

Yet even Lt. Col. A, whose full name is being withheld per military protocol, allowed that the creation of these fake apps, and the social engineering behind them, “exhibits a sophistication way above the average.”

The question, though, is how difficult all of this is, actually, to pull off.

In the murky world of online warfare, drawing clear conclusions often is difficult. The easy proliferation of offensive cyber weapons in recent years has created a crowded battlefield where states, criminals, and non-state actors—like terror groups—meld together.

“The arms race is changing,” Lt. Col. A said. “Kinetic weapons cost a lot of money and are visible, unlike cyber-kinetic weapons. A small amount of money [in this space] in a short period of time” can have a major impact.

It’s difficult to overstate the low barrier to entry in cyber warfare. Fake Facebook accounts with a fleshed out history can run just a few dollars on the Dark Web. “Spoofed” phone numbers, to make it seem like a call is coming from, say, Israel, can run a few hundred dollars. Cyber tools are available for purchase, too, as are the services of freelance hackers. But this may not even be necessary, according to Ohad Zaidenberg, a researcher at ClearSky Cyber Security, an Israeli firm, who told The Daily Beast that some software can be found easily via a simple Google search.

“It’s not only an issue of pure technical sophistication that dictates effectiveness, there are multiple parameters,” Zaidenberg added, referring to Hamas’s cyber campaigns against Israel. While one group within the wider umbrella of Hamas’s cyber-unit is known to develop its own viruses, another group uses generic tools that can be found on the internet. The bottom line for any such “political attacker” (as opposed to simple criminals) is, according to Zaidenberg, “the need to understand the target, otherwise there would be no reason to go after it.”

Clearly Hamas views young (male) IDF conscripts as the soft underbelly of the IDF’s defenses, and has therefore poured time, resources, and energy into multiple “honeypot” efforts. To do this effectively, however, Hamas needed to develop operatives with good Hebrew language skills and Israeli cultural awareness. A fake rocket alert app could be technically perfect, but the timing of its launch into the world is arguably more crucial. It’s not a coincidence that Hamas chose an escalation in rocket fire from Gaza in mid-2018 as the moment to deploy it, knowing full well nervous Israelis would flock to the Google Store looking for such a product.

While it’s difficult to estimate how many personnel Hamas would need for these various cyber operations, it’s almost a certainty they didn’t all materialize from Gaza. “You can send someone to study basic computing skills at, for example, the American University of Beirut or a Western university, and they can work from there. This is the huge difference with cyber, you don’t need to sit in Gaza,” Lt. Col. A said. Referring to your faithful correspondent, he observed: “You sit in Tel Aviv and write for the U.S., right?”

As if to prove this last point regarding the diffusion of the cyber threat, last May the IDF for the first time used jet fighters to attack the Hamas cyber headquarters in Gaza after an attempted cyber attack on what Israel said was part of its “civilian infrastructure.”

“Hamas no longer has cyber capabilities after our strike,” IDF spokesperson Ronen Manelis told reporters. Yet the latest Hamas cyber campaign revealed by the IDF last week is known to have started only a few months later.

“There will be no immunity,” said Lt. Col. Conricus, the IDF spokesman. “Hostile actions by Hamas in the virtual world will have consequences in the real world.”

The cat and mouse game between Hamas and Israel in the cyber realm undoubtedly will continue—and escalate. Cyberwarfare "is easy, available and cheap. Not for nothing is Hamas investing so many resources into it,” Lt. Col. A told The Daily Beast. “The threat is growing. We won’t be going back.”

No comments:

Post a Comment