By VAIHAYASI PANDE DANIEL

When Rediff.com spoke to several general practitioners, who have clinics near Mumbai's slum localities, or whose patients come from the lower economic classes, they didn't have answers on how social distancing could be effected in the slums.

When Rediff.com spoke to several general practitioners, who have clinics near Mumbai's slum localities, or whose patients come from the lower economic classes, they didn't have answers on how social distancing could be effected in the slums.

Says Dr Vivek Korde, a GP from Sewri, south central Mumbai, with a laugh: "How it can work? We cannot just think of it!"

General practitioner Dr Prakash Tathed has a clinic in the Grant road area of south Mumbai and sees patients from all backgrounds.

"Social distancing in Mumbai is very difficult, because you may stop the vehicles, you may stop the local trains, But what about those places where people live in a jhoppadpattis (shanties)?" asks Dr Tathed.

"They are so close together, you can't have a ten-inch distance also," adds Dr Tathed. "That's very difficult. Thankfully, still, it has not gone in that area. But when it will go, we cannot know. It will be seen after 15 days or so."

*IMAGE: Migrant workers rest inside their one room dwelling in Mumbai. Photograph: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters

A doctor working at suburban government hospital, who did not wish to be named, says: "Social distancing I don't think at a lower middle-class level will have much effect. For example, my domestic worker, her two sons are not going to work. She lives in a single room ten by ten. They have no choice but to be close to each other."

"Social distancing can't be done. It is mainly meant for the middle or upper middle class."

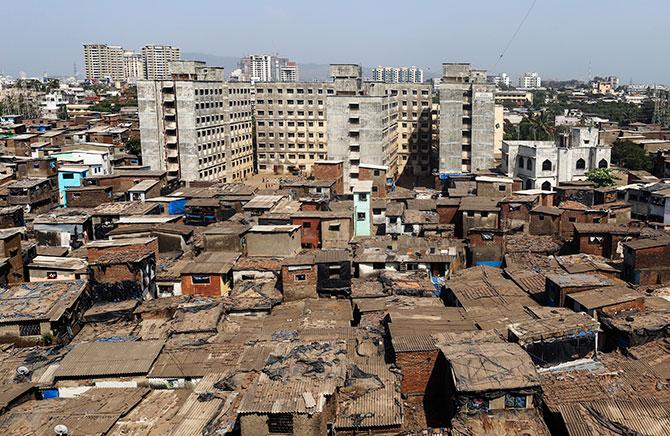

IMAGE: Multi-storey slums in Mumbai. Photograph: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters

Dr Sanjay (named changed), a former BMC doctor, says that in many municipal wards the lanes are very narrow and allow the passage of one person at a time.

"They throw everything into the galli and someone has to go and remove the garbage. And there's old drainage. Now you will find multi-storey slums. One, second, third floor. It's really difficult in multi-storey slums."

As per recent estimations, Mumbai now has a population of 22 million* and about 41 per cent of that live in slums.

Hence, approximately 9 million people in Mumbai live in areas where homes are hardly two metres apart.

And water may be scarce.

And isolation close to impossible.

IMAGE: People gather to fill drinking water from a common municipal tap at a slum area in Mumbai. Photograph: Punit Paranjpe/Reuters

But Dr Deven Naik, who has a practice in the Parel area, south central Mumbai, did have a thought on how social distancing might be achieved.

"The thing is that the people are living in such proximity that it is hard to isolate then at their place. What we are talking about is quarantining them at their home. That won't be possible in slums, or small chawls, where nine to 10 people live in one 10 by 10 room," explains Dr Nairk.

"So the government should think of taking the suspected cases (from the slums) and isolate them elsewhere. I don't have any idea how it can be done. But they can take the schools or grounds," Dr Naik adds.

"They have to make some makeshift arrangements for people living in such proximity like chawls and slums and all that. They can't be relied upon to isolate themselves in their homes, where basic facilities like toilets are not in their homes," says Dr Naik.

"They have to go somewhere outside for that. The concept of quarantine will not work there in those areas."

IMAGE: A child takes a bath in a slum in Mumbai. Photograph: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters

While speaking about this problem, which is not just specific to Mumbai, Dr Roopa Mankaikar, who also practices in Parel, tentatively offers the hope that people living in close, crowded, quarters may have stronger immunity in any case.

Says Dr Mankaikar: "They may be already having immunity against bad viruses because already they are living in such a poor hygienic condition. That may help us or not. I don't know. Might be possible."

She is also concerned about the doctor dispensaries inside these packed areas.

"Clinics are also very small in slums. Hardly four feet area around. Very difficult... For them to go to the hospital and check for this swab, it is not possible for everybody."

Dr Korde adds, with a touch of grim humour: "We can only pray to god and god is not there. We are helpless people. We cannot take any measure which China could take. Italy can take. We cannot take in our metro city. This is a mega city, something more than mega city."

In addition to social distancing, the other government directives are about containment and isolation of those with travel history and tips on washing hands.

For those living in slums is the use of a sanitiser or multiple washing of hands feasible?

The verdict on this is mixed.

The government hospital doctor says her domestic help, and the people who she sees from poorer areas, had sanitiser before she did.

"All my three bais are using sanitiser and they are using masks. They are doing it because all the time it is coming on the television. Television is a strong influencer."

These doctors say too that most slums have enough water available.

Dr Sanjay, the former BMC doctor, confirms: "Mumbai has a good supply of water."

Dr Tathed is of the opinion that it's more about explaining how to wash hands.

"Practically everybody is having phones. Everybody has mobile phones. Even those working as housemaids they also have WhatsApp and all this info is being disseminated to them. About washing hands and wearing masks."

IMAGE: High-rise residential buildings are seen behind a slum in Mumbai. Photograph: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters

But Dr Korde, who now works as an activist, says he won't say it's not possible, but has more to add: "We are very irresponsible people. (Thursday) I went to a stationery store to buy a pen refill. That fellow was literally wiping his nose with his hand and with those hands he gave me the refills. I scolded him."

But people are hygienically not literate.

"You ask them to wash their hands. They will wash their hands for five seconds. They should understand that this is necessary for their life! The overall view is that nothing will happen to us."

IMAGE: Residents fill water in a Mumbai slum. Photograph: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters

Dr Naik has another take.

According to him, since water is stored in drums in slum homes, water can easily get contaminated and washing of hands not a workable or fool-proof solution.

"Water is a very big problem. They don't have water. They just fill up some water in drums and all that. You can't expect them to wash hands frequently."

"Washing your hands at a tap (is different from) washing your hands from a drum; it can contaminate the whole source of water... And water scarcity also an issue in these areas."

Dr Sanjay had a concern about washing of masks as opposed to hands.

"People don't know how to decontaminate the mask or the cloth masks. They don't understand what is the protocol for decontaminating this mask or the cloths they are using for protection... Most people are using the mask and throwing it."

And the accumulation of discarded masks, all over the place, could be an additional health hazard in Mumbai, he points out.

A certain degree of segregation of the people of the slums from wealthier classes, for their own safety, is considered another more radical but safer option.

Covid-19 is a disease that is travelling from higher economic stratas to lower ones, where folks are less equipped to deal with it.

Creating a distance for the poor from this "imported" disease is suggested.

Or as Dr Tathed puts it: "We should restrict people to their locality only."

IMAGE: Residents in Dharavi, north central Mumbai, one of Asia's largest slums. Photograph: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters

Dr Roopa has noticed that city residents are giving their domestic help a break: "Near my clinic there are many high rises. People (in those buildings) have told their maids don't come."

Says Dr Korde: "We always blame poor people that they bring TB (tuberculosis) and this and that. And that because of them we are suffering. Now the rich people are giving suffering to the poor."

"The best thing the government can do for the poor and people living in slum areas, they should provide them adequate rations, all required things, the government should take care of all those families for a month and lock them to their home only," says Dr Korde.

"At the same time all other people should be locked in their houses for at least for three weeks. That's the only way!"

IMAGE: A municipal worker fumigates a slum area to prevent the spread of dengue fever and other mosquito-borne diseases in Mumbai. Photograph: Shailesh Andrade/Reuters

Dr Naik concurs: "You have to supply them with their essentials. They are daily wagers. So if they are not going to work, they are not going to earn."

"They should be) provided with one month rations. Supplies kept near their homes so they won't have to come out."

After quarantining these areas, Dr Naik suggests daily checks.

Municipal workers, he says, are anyway going to homes in slums checking if there are cases to be isolated.

"Workers are going to homes and asking whether you have cold or cough. They are doing it on a daily basis now."

IMAGE: A girl jumps rope in Dharavi. Photograph: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters

The former BMC doctor says surveillance is something the municipal corporation is very good at and "locking people into their domain" is a step that should be considered.

"We can track any patient at any moment. We have a massive infrastructure and massive outreach. We have a very good slum-based networking," he adds.

Dr Naik -- who is thinking of giving separate timings in his clinic for those with cough, cold and fever -- believes that that his patients from poorer backgrounds have quite clearly understood how serious the disease.

But that is not necessarily an ideal situation.

Often confusion follows.

"There is confusion in everybody's mind, like including me, about what the government is doing and how it is going to stop it and what is the future of these people," says Dr Naik.

"The amount of information being bombarding on the people is leading to panic. And we don't have anything to do for this panic. That that can lead (for those living in the slums) to a lethargy of: What will happen, will happen, if you don't have a measure of control for a thing."

"Bhagwan dekh lega kya karna. Jo sabka hoga humara hoga. Kya karein? (God will look after us, what happens to everyone will happen to me too, so why worry?)"

The fatalism arises, says Dr Naik, because of their situation, especially among daily-wage earners.

More prosperous people have all kinds of facilities available to them and the ability to stockpile groceries and lockdown.

"They don't have the facilities to lock themselves in their houses," says Dr Naik.

"They are totally dependent on the government. And (their) god."

No comments:

Post a Comment