By: John Calabrese

Introduction

Over the years, unremitting hostility between the United States and the Islamic Republic of Iran has created opportunities as well as dilemmas for the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The Trump administration’s unilateral withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in May 2018, and the subsequent adoption of a “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran, presented mixed challenges and opportunities for the PRC. Beijing has sought to exploit the rift between Washington and Tehran without further fueling Sino-American tensions.

For the past year, Washington and Tehran have been locked in an action-reaction cycle of escalation. This dangerous spiral reached new heights with the January 2 U.S. drone strike that killed Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Quds Force commander General Qasem Soleimani, which was followed by retaliatory Iranian missile attacks on two coalition bases in Iraq that injured dozens of American troops. Although both sides managed to pull back from the brink of war in early January, underlying tensions remain—as does the possibility of a more direct military confrontation.

In what manner and to what extent has the current unstable situation affected China’s interests in, and relationship with, Iran? What is the likelihood that, as this latest round of high-stakes poker between Washington and Tehran continues to unfold, Beijing will seize it as yet another opportunity to profit from America’s entanglements in the wider Middle East?

China’s Not-So-Special “Special Relationship” with Iran

During the 1990s, China’s growing energy needs, and Iran’s abundant oil and gas resources, formed the basis of a partnership that has since broadened and deepened. In the early 2000s, China’s relations with Iran began to mature, thanks largely to U.S. pressure on Europe, Japan, and Russia to reduce their trade with (and investments in) Iran. Cut off from the West, Iran adopted a “Look East” economic strategy of which China became the principal beneficiary, emerging as Iran’s most important economic partner (Radio Farda, August 3, 2019). Chinese companies tapped into the underserved Iranian market and played key roles in expanding Iran’s refining capacity, injecting capital into its extractive industries, and developing its transportation infrastructure.

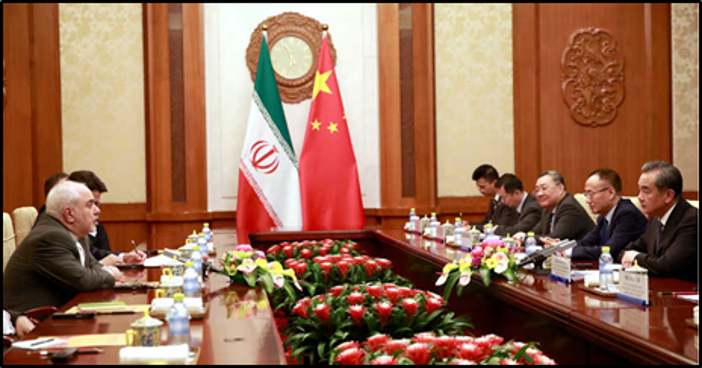

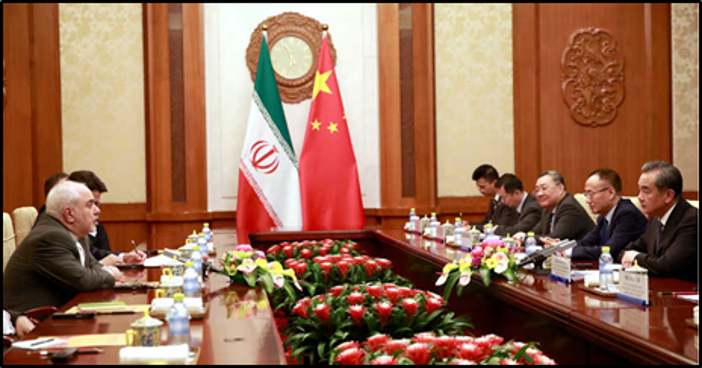

The launch of President Xi Jinping’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has boosted Iran’s potential value to China as a critical nodal point in an evolving regional transport network. As a Caspian Sea littoral state whose southern flank lies at the narrowest point of the Persian Gulf, connecting the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean, Iran is poised to become a link in a contiguous China–Europe rail route that bypasses Russian territory. Iran is also situated to become the hub of the International North–South Transit Corridor (INSTC) (China Brief, December 10, 2019). In the wake of Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif’s August visit to Beijing, one petroleum industry publication characterized the September 2019 revision of the Sino-Iranian strategic partnership as “a possible seismic shift in the global hydrocarbons sector” (Petroleum Economist, September 3, 2019).

For these reasons, and because Iran has also served as a point of leverage against the United States—the principal geopolitical and military competitor for both Iran and China—some Western commentators have accorded the country an outsized importance in PRC foreign policy. [1] However, these claims seem misplaced. To be sure, Beijing has come to regard the Middle East as part of its extended periphery—for better and for worse—and no doubt considers Iran as a valuable regional partner. Nevertheless, the Western Pacific and China’s immediate neighbors remain its highest priorities. Furthermore, China’s relationship with the United States, though fraught, far surpasses in significance its partnership with Iran. The United States’ concurrent pressure on China and Iran can be said to have supplied Beijing with an opportunity to cooperate with Tehran in countering the United States—though not at the risk of countenancing a confrontation that could prove disastrous for China’s global interests, which extend far beyond its relationship with Iran (Al-Monitor, May 13, 2019).

China’s “special relationship” with Iran is actually not so special. Its “comprehensive strategic partnership” agreement with Iran parallels similar agreements with many other countries—to include Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), states with which Iran is sharply at odds (Project on Middle East Political Science, March 2019; CNTV, January 20, 2016; SCMP, July 21, 2018). Moreover, there is no evidence that China privileges its relations with Iran over those with the Gulf Arab states. In economic terms, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries are arguably more attractive trading partners for China than a revisionist Iran. [2] Saudi Arabia is now China’s top oil supplier, and Chinese firms have committed $123 billion in investments and construction contracts to the Gulf Arab countries since 2013 (Foreign Policy, May 16, 2019). China has a large expatriate population in the UAE, further increasing the costs of a potential conflict (The National (UAE) , July 31, 2019). Furthermore, the PRC’s investments in Iran pale in comparison to those made in Pakistan, which hosts the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), arguably the crown jewel of China’s entire BRI program (China Brief, July 31, 2015; China Brief, January 17).

Although some of the grand strategic interests of China and Iran overlap, they have divergent ideological orientations and approaches to regional and international issues. Iran’s repeated threats to close the Strait of Hormuz have sounded alarms in Beijing. Iran’s support for religious insurgencies is also a source of consternation for Chinese leaders—who claim to face Muslim terrorist threats within their own borders, and cite alleged Islamic militancy as the justification for repressive “de-extremification” measures in the PRC’s western province of Xinjiang (China Brief, April 24, 2019). Iran’s possible development of nuclear weapons capability—even if it were to act as a check on U.S. influence—is also sharply at odds with the PRC’s official non-proliferation stance and overriding interest in regional stability. Finally, Iran’s regional ambitions seem to stretch beyond simply advancing Silk Road integration, and may not necessarily be congruent with Chinese aims in the long-term. Image: Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif (left) and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi (far right) conduct discussions at the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse in Beijing (August 26, 2019). Zarif’s visit produced pledges to upgrade the “comprehensive strategic relationship” between the two countries. (Image source: Al-Monitor)

Image: Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif (left) and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi (far right) conduct discussions at the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse in Beijing (August 26, 2019). Zarif’s visit produced pledges to upgrade the “comprehensive strategic relationship” between the two countries. (Image source: Al-Monitor)

Image: Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif (left) and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi (far right) conduct discussions at the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse in Beijing (August 26, 2019). Zarif’s visit produced pledges to upgrade the “comprehensive strategic relationship” between the two countries. (Image source: Al-Monitor)

Image: Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif (left) and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi (far right) conduct discussions at the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse in Beijing (August 26, 2019). Zarif’s visit produced pledges to upgrade the “comprehensive strategic relationship” between the two countries. (Image source: Al-Monitor)

Dividends Deferred

The fact that China has never acceded to U.S. pressure to “isolate” Iran reflects an overriding concern in Beijing to avert a situation in which either Iran implodes, or in which the current regime is rendered so desperate that it lashes out. Both scenarios would destabilize the Middle East and obstruct China’s access to regional energy markets. On past occasions when Iran’s relations with the U.S. sharply deteriorated, Beijing showed itself willing to assume a modest level of risk. During the period 2010-2016 (i.e., prior to the signing of the JCPOA), China did not ban all energy trade with Iran (Congressional Research Service, November 29, 2017). When Iran was blocked by sanctions from accessing foreign exchange, China settled the trade balance in goods rather than hard currency (Middle East Institute, May 9, 2018).

When the JCPOA was implemented, the PRC was the least hesitant of Iran’s foreign economic suitors to restart trade relations (SCMP, December 1, 2017). During a January 2016 visit to Tehran, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary and PRC President Xi Jinping sketched out a plan with his counterpart, President Hassan Rouhani, to broaden relations and increase bilateral trade to $600 billion within a decade (China Brief, March 7, 2016). The next month, following the old Silk Road trading route, the first container train of commercial goods from China entered Iran through the border town of Sarakhs. Iran’s future and that of China-Iran relations looked more promising than they had in decades.

However, two years can make a dramatic difference. With President Trump’s May 2018 announcement of U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA, China-Iran relations reverted to a familiar pattern. China continued to buy crude oil from the Islamic Republic even after the Trump administration ended sanctions waivers for all Iranian customers, although Chinese purchases were sharply reduced (SP Global, January 10). Sanctions have taken a toll on China-Iran commercial relations. Trade between both nations plummeted by 34.3 percent between 2018 and 2019 (Financial Tribune (Iran), January 26). Key Chinese state-owned enterprises have pulled backed from their investments in Iran (MarketWatch, October 6, 2019). Meanwhile, Chinese companies have hedged against the dangers of overreliance on Iranian oil shipments by expanding their partnerships with other suppliers within and beyond the Middle East. In 2019, China’s purchases from Saudi Arabia and Russia, its top two oil suppliers, rose by 4 percent and 9 percent, respectively (Reuters, January 30).

Following an August 2019 visit to Beijing by Foreign Minister Zarif, the two countries reportedly agreed to update the “comprehensive strategic partnership” to include an unprecedented $400 billion of investment in the Iranian economy, in return for Chinese firms maintaining first right of refusal to participate in any and all petrochemical projects in Iran (Tasnim News, September 17, 2019; China Brief, November 1, 2019). However, this reported $400 billion bonanza has yet to materialize.

The Trump administration has not yet penalized the People’s Bank of China or energy giant Sinopec for doing business with Iran—presumably to retain some leverage over Beijing, or to avoid a further deterioration of the bilateral relationship. Nevertheless, Washington’s crackdown on Chinese tankers carrying Iranian oil (as well as other entities found to have breached U.S. sanctions) has continued apace (SCMP, July 23, 2019; SCMP, September 26, 2019). It is perhaps telling that the recently concluded Phase 1 U.S.-China trade agreement contains a Chinese pledge to buy over $50 billion more in U.S. oil and related products (SCMP, January 14).

The war of words between Washington and Beijing has continued unabated in the wake of the signing of the Phase 1 trade deal. China slammed the latest sanctions against Iran and called for the United States to “immediately correct the wrong approach” (VOA (Iran), September 26, 2019). For its part, the United States accused China of siding with Russia to block a U.N. Security Council resolution condemning an attack by pro-Iranian militia groups on the American Embassy in Baghdad in December (Reuters, January 6). In a 25 January interview, U.S. Special Representative on Iran Brian Hook charged China with “funding Iran’s terrorism through oil purchases” (SCMP, January 25).

During a meeting with Iranian Foreign Minister Zarif in Beijing last May, Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi (王毅) stated that China “supports the Iranian side to safeguard its legitimate rights and interests” (China Daily, May 18, 2019; PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs, May 17, 2019). However, since then Beijing’s actual support has not amounted to much. Amid heightened tensions between the United States and Iran, the PRC made a point of downplaying the significance of its participation in December 2019 joint naval drills with Russia and Iran in the Gulf of Oman —as if to underscore its determination not to be drawn into Middle East conflicts (Xinhua, December 26, 2019; China Brief, January 17). Foreign Minister Wang Yi criticized the U.S. strike that killed General Soleimani as a “military adventurist act”—and later, meeting with his Iranian counterpart in Beijing, Wang called for the two countries to “stand together against unilateralism and bullying.” However, Wang accorded top priority to the nuclear issue, strongly urging Iran to remain in the nuclear deal (SCMP, January 1).

Conclusion

While China’s engagement with Iran has become more extensive over the past two decades, the relationship has been continually tested. The two sides have alternated between reaping the rewards of their burgeoning partnership, and finding themselves in the crosshairs of U.S. policy. When U.S.-Iran tensions briefly ebbed, Western companies were reluctant to rush back to Iran—which left their Chinese counterparts in an advantageous position. However, for the most part the chronically embattled Islamic Republic has been a troublesome partner for Beijing. China’s recent efforts in regards to Iran can be summed up as consisting mainly of: providing assurances of its continued commitment to strengthening the relationship with Iran; urging both the United States and Iran to remain calm and exercise restraint; and vowing to support diplomatic initiatives aimed at preventing conflict. Amid all of this, Beijing has encouraged efforts, however unlikely, to rescue the remnants of the 2015 Iran nuclear deal to which China was a co-signatory (SCMP, January 8).

For Beijing, the task of balancing competing interests has become ever more complex: its relationship with the United States has grown more contentious, and in the Gulf Region the Saudi-Iran rivalry has become more toxic. Beginning in the period prior to the signing of the JCPOA (and continuing since the deal began to unravel), Beijing has offered both diplomatic support and an economic lifeline to Tehran. However, China is not, and nor does it aspire to be, Iran’s security guarantor—a fact that Iranian leaders perforce are keenly aware of, and which could partly explain Tehran’s cultivation of a network of regional proxies and partners.

The 2017 U.S. National Security Strategy designates China as one of two “revisionist powers,” and identifies “strategic competition” with China in all domains as a driving factor of American foreign policy. The same document refers to Iran as a “menace” to the region it inhabits, and asserts that a core objective of the Trump administration’s Middle East strategy is “systemic change in the Islamic Republic’s hostile and destabilizing actions” (NSS, 2017). These two separate strands of U.S. policy are inextricably intertwined. Whatever the outcome of the November 2020 American presidential election, a U.S. policy reversal in either case is implausible. Absent a fundamental change in Iranian foreign policy behavior or in the regime itself, Sino-Iranian relations will continue to be conditioned by U.S. policy—and constrained by it.

Dr. John Calabrese teaches U.S. foreign policy at American University in Washington, DC. He also serves as a Scholar in Residence at the Middle East Institute, where he directs the Middle East-Asia Project (MAP). He is the Book Review Editor of The Middle East Journal and previously served as General Series Editor of MEI Viewpoints. He is the author of China’s Changing Relations with the Middle East and Revolutionary Horizons: Iran’s Regional Foreign Policy. He has edited several books and written numerous articles on the international relations of the Middle East, especially on the cross-regional ties between the Middle East and Asia.

No comments:

Post a Comment