By Ibrahim Al-Marashi

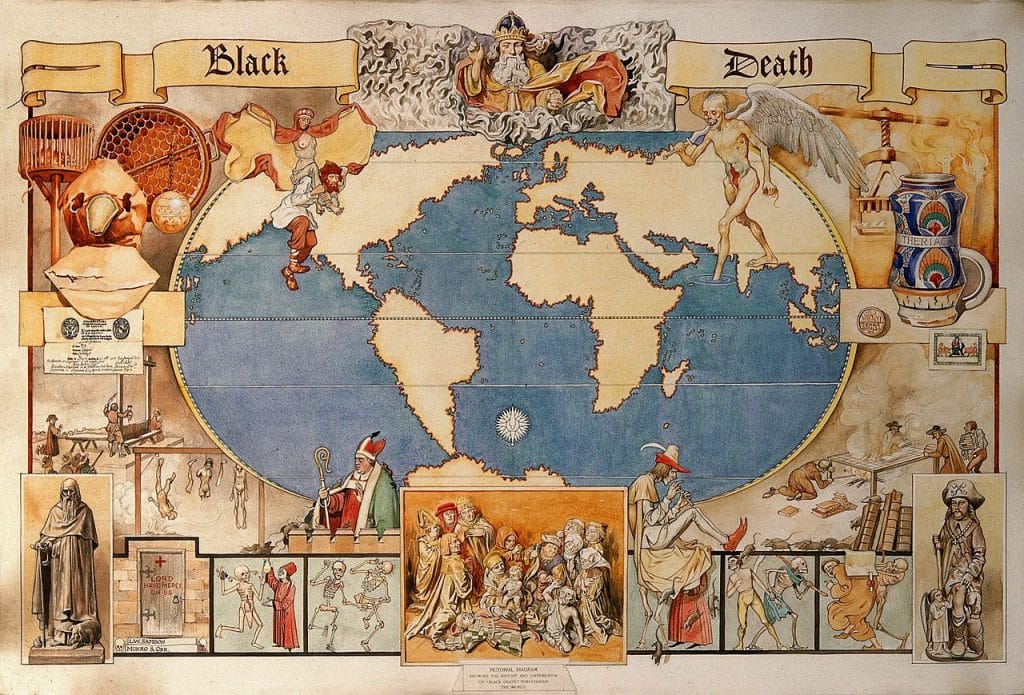

"The black death," a watercolor painting by Monro S. Orr. Credit: Creative Commons.

As the novel coronavirus has spread, so too have a flurry of myths and disinformation about it, often perpetuated by mainstream and social media. Many of these myths are medical. For example, although wearing a surgical mask will not protect you from contracting the illness—viruses are too small to be screened out—healthy people around the world have rushed to buy them.

But the myths are also social. A perfect example is the false assertion that the coronavirus emerged because a Chinese woman in Wuhan ate bat soup. (Though bats may have been the source of the virus, the video that purportedly substantiates the claim was filmed in the South Pacific island of Palau, not China, for the popular online travel show of a Chinese video blogger named Wang Mengyun.)

Although public health experts have worked hard to debunk many of these myths, popular history can also be a valuable tool for putting the outbreak in context, dispelling untruths, and allaying fears among a wider public. The history of the Black Death, the Spanish flu, and smallpox all hold valuable lessons.

Coronavirus and zoonoses. The recent coronavirus is just another instance in the long history of zoonoses—diseases that jump from animals to humans. The domestication of the horse led to the virus responsible for the common cold in humans, while the domestication of chickens gave humans chickenpox, shingles, and various strains of the bird flu. Pigs were the source of influenza, and measles, smallpox, and tuberculosis emerged from cattle. When a virus successfully jumps species from an animal to a human (“patient zero”), and that version of the virus in turn succeeds in making the jump to a second human, those two people become the first two human vectors of human-to-human virus transmission.

Three-quarters of infectious diseases are the result of zoonotic spillovers, and the novel coronavirus is no exception. The term “coronavirus” refers to a family of viruses shaped like a crown, and it accounts for about 10 percent of common colds in humans. (Rhinoviruses are the predominant cause of the common cold.) Novel coronaviruses have made the jump into the human population on three occasions in the 21st century, each time causing a deadly pandemic: SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) in late 2002, MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome) in 2012, and COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) at the start of this winter.

Lessons from the Black Death. The other germ that has been part of humanity’s long history of disease outbreaks is not a virus but the bacterium Yersinia pestis, responsible for the mid-14th century epidemic of the bubonic plague, colloquially referred to as “the Black Death.” In popular historical memory, the origin of the Black Death is often associated with China, but other studies situate the origin in the interior of Central Asia—possibly southeastern Kazakhstan—from which it then spread to China and Europe. Pinpointing its exact origin is not merely an academic exercise; it has implications for the xenophobia that sometimes accompanies with disease outbreaks.

While the origin of the Black Death is often associated with rats and fleas, the original vector was most likely a mammal such as the marmot or the great gerbil. Both of these species are social rodents, with marmots being one to two feet tall and great gerbils about eight inches; marmots in particular are so ubiquitous that Marco Polo referred to them as “Pharaoh’s rats.” A marmot or great gerbil may have been bitten by a flea that then carried the bacterium to a human.

Another pandemic of the bubonic plague emerged in the southwestern Chinese province of Yunnan in 1894, spread to Canton and Hong Kong, and reached Bombay by 1896. By 1900 it had reached ports on every continent, carried by infected rats travelling the international trade routes on steamships. Over a 30-year period this outbreak killed 12 million people in India alone.

Xenophobic tropes became commonplace; political cartoons and newspaper covers in California depicted Chinese-Americans eating rats in crowded, unclean living spaces. As Jessica Hauger recently wrote in the Washington Post, “The idea that Chinese-Americans were a threat to public health also motivated San Francisco’s authorities to quarantine Chinatown and carry out unconstitutional searches and evictions during an outbreak of plague in 1900.” Similarly, Honolulu’s Board of Health quarantined that city’s Chinatown, incinerating garbage and sparking a fire that burned 4,000 homes.

The COVID-19 outbreak has sparked renewed interest in the Black Death. One Washington Post article warns that treating the coronavirus like the Black Death is “dangerous,” arguing that it perpetuates a false “outbreak narrative” that depicts disease outbreaks as always following the same trajectory and having the same level of severity. Indeed, comparing COVID-19 with the Black Death only exacerbates fears among the public even though today’s pathogen is by no means as fatal as the medieval pandemic.

Lessons from the Spanish flu. The Spanish flu holds key lessons concerning the need for transparency as well as the effectiveness of quarantines. The Spanish flu pandemic, which was most likely avian in origin, infected one-fifth of the world’s population and killed 50 million people—much more than the World War that preceded it. World War I itself, involving the mass movement of soldiers and war materiel, was partially responsible for the spread of the virus around the world.

On the issue of transparency, the story of the disease’s name is revealing. It was called “Spanish” flu not because it originated in Spain, but because Spain was the first country to widely publicize the outbreak. Since Spain was not a belligerent in World War I, it did not have wartime censorship in place, while other nations censored the news of the pandemic. Because of the headlines and coverage in the Spanish press, many people simply assumed that’s where the outbreak started. (For their part, Spaniards assumed it came from France and called it the French flu.)

The latest outbreak is also the result of a lack of transparency by officials in Wuhan who ignored and suppressed initial warnings. This resulted in little critical information being released in a timely manner, depriving national leaders in Beijing the opportunity to implement informed decisions.

Transparency is essential for the public trust that is needed to control the epidemic. Trust determines whether the public has confidence in government action and listens to their advice. Trust is also necessary for people to believe the public education announcements about how to avoid infection. China and Iran, for example, broadcast public health information via state-run television, and these measures are essential to dispel rumors and prevent the public from turning to ill-suited folk remedies, a battle for credibility both states might have lost in light of the initial coverup in China and the failure to acknowledge the accidental downing of a civilian airliner in early January by Iran.

The Spanish flu provides valuable historical context when it comes to quarantines too. The quarantine, coming from the Italian “quaranta giorni,” meaning 40 days, was first implemented in the mid-14th century to keep the bubonic plague from spreading from incoming ships. Researchers led by Howard Merkel published a study evaluating the effectiveness of isolating the sick in this manner, drawing on data from the 1918 Spanish flu outbreak. They found that stopping an outbreak requires early action that uses a combination of non-pharmaceutical measures such as closing schools and banning public gatherings. Quarantines alone, they found, are too draconian and unlikely to be effective.

But in the case of the coronavirus, China’s authorities placed Wuhan and more than a dozen other cities under lockdown, completely isolating an estimated 50 million people from the rest of the world, and penning the sick in with the uninfected—the largest such effort in human history. (One medical historian labeled it “the mother of all quarantines.”) There were concerns about how to supply those within the quarantine zone with food, water, and other supplies, and other practical considerations: How would people get to work? Would families be separated? Would every road be blocked?

Making matters worse, local officials in Wuhan did not act early enough—all-too-typical of what happens between the first indications of an epidemic and solid confirmation. They first ignored the scientific findings and allowed large public gatherings to take place, and then enacted the quarantine eight hours after announcing it—allowing perhaps five million people to leave the city after the beginning of the outbreak and before the lockdown. Merkel, writing for the New York Times, called China’s draconian quarantine “too much too late.”

Lessons from smallpox. While an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal invoked an unfortunate historical trope in referring to China as “the Sick Man of Asia” (echoing descriptions of the Ottoman Empire as “the Sick Man of Europe”), one of that publication’s popular history articles on zoonoses offers valuable lessons from smallpox—as well as cause for optimism from the past.

The article points out that smallpox may have been the cause of a plague that killed 20 percent of the population of ancient Athens in 430 BCE, an event that the historian Thucydides survived and later described. Over the course of the 20th century, smallpox is estimated to be responsible for 300 million deaths.

Yet from 1966 to 1977, the World Health Organization initiated an international vaccination campaign that successfully eradicated the disease, representing one of the most substantial successes in global public health of the 20th century. The eradication program worked due to the improvised and unorthodox way in which the WHO team worked around extraordinary physical, technical, and bureaucratic obstacles. Articles by the WHO published in the Journal of Clinical Pathology in 1975 describe smallpox health workers in remote parts of the world being kidnapped, held for ransom, threatened with execution, or walking hundreds of miles to check out reported cases of the disease—but refusing to leave their assigned areas.

Global cooperation today to contain coronavirus will require efforts on a similar scale. Like with climate change, world-historical threats call for world-historical levels of cooperation. China and the United States will have to work closely together, in tandem with subnational governments, private companies, and nongovernmental organizations, to stop the virus’s spread.

History repeats itself. If there is a lesson from the recent past, be it SARS, MERS, or COVID-19, it is that these outbreaks need to be dealt with proactively, with a heavier emphasis on prevention, says disease ecologist Peter Daszak in a recent New York Times article. Modern societies treat pandemics as a disaster-response issue, waiting for them to happen and then reacting and hoping to quickly find a vaccine. This, Daszak argues, is a poor approach, and more could be done to prepare for outbreaks in advance.

In terms of what individuals can do in the face of the current outbreak, the best measures include maintaining good hand hygiene and not touching one’s own face. This is not only what public health experts have recommended, it is also what history has proven effective. During the Crimean War, Florence Nightingale believed the main problems were diet, dirt, and drains—she brought food from England, and cleaned up the kitchens and hospital wards. At her behest, a Sanitary Commission, sent by the British government, arrived to flush out the sewers and improve ventilation. Invoking Nightingale’s precedent is a reminder, then as now, about the unsung heroes, the medical professionals on the front lines of containing this pathogen.

The other heroes are those who were quick to seek medical advice and voluntarily quarantine themselves. In this regard, taking the measure of quarantining oneself, even if to prevent the spread of the flu or any other respiratory virus, will relieve the burden on overextended public health institutions.

Finally, during the Black Death, fake news then included attributing the disease to bad air and miasmas, as well as to Jewish communities. Today, coronavirus has been falsely attributed to biological weapons labs and the Gates Foundation. As an individual, one can fight this virus by debunking the viral myths that spread today, as they did centuries ago.

No comments:

Post a Comment