ZEYNEP TUFEKCI

You may be wondering if the Iowa caucus chaos is a hit job by election-meddling Russians. The morning after caucus-goers filed into high-school gyms across Iowa, the state’s Democratic Party is still unable to produce results. The app it developed for precisely this purpose seems to have crashed. The party was questioned before by experts about the wisdom of using a secretive app that would be deployed at a crucial juncture, but the concerns were brushed away. Troy Price, the state party’s chairman, claimed that if anything went wrong with the app, staffers would be ready “with a backup and a backup to that backup and a backup to the backup to the backup.” And yet, more than 12 hours after the end of the caucus, they are unable to produce results. Last night, some precinct officials even waited on hold for an hour to report the results—and got hung up on.

You may be wondering if the Iowa caucus chaos is a hit job by election-meddling Russians. The morning after caucus-goers filed into high-school gyms across Iowa, the state’s Democratic Party is still unable to produce results. The app it developed for precisely this purpose seems to have crashed. The party was questioned before by experts about the wisdom of using a secretive app that would be deployed at a crucial juncture, but the concerns were brushed away. Troy Price, the state party’s chairman, claimed that if anything went wrong with the app, staffers would be ready “with a backup and a backup to that backup and a backup to the backup to the backup.” And yet, more than 12 hours after the end of the caucus, they are unable to produce results. Last night, some precinct officials even waited on hold for an hour to report the results—and got hung up on.

If the Russians were responsible for this confusion and disarray, that might be a relatively easy problem to fix. This is worse.

It appears that the Iowa Democrats nixed the plan to have precincts call in their results, and instead hired a for-profit tech firm, aptly named Shadow, to tally the caucus results. (As if the name weren’t enough to fuel conspiracies, the firm is run by an alum of Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign.) The party paid Shadow $60,000 to develop an app that would tally the results, but gave the company only two months to do it. Worried about Russian hacking, the party addressed security in all the wrong ways: It did not open up the app to outside testing or challenge by independent security experts.

This method is sometimes dubbed “security through obscurity,” and while there are instances for which it might be appropriate, it is a fragile method, especially unsuited to anything public on the internet that might invite an attack. For example, putting a spare key in a secret place in your backyard isn’t a terrible practice, because the odds are low that someone will be highly motivated to break into any given house and manage to look exactly in the right place (well, unless you put it under the mat). But when there are more significant incentives and the system is open to challenge by anyone in the world, as with anything on the internet, someone will likely find a way to get the keys, as the Motion Picture Association of America found out when its supposedly obscure digital keys, meant to prevent copyright infringement, quickly leaked. Shadow’s app was going to be used widely on caucus day, and independent security experts warned that this method wasn’t going to work. The company didn’t listen.

If Shadow had opened up the app to experts, they likely would have found many bugs, and the app would have been much stronger as a result. But even that process would not have made the app secure. An app that is downloaded onto the phones of thousands of precinct officials across Iowa—with varying degrees of phone security and different operating systems—cannot be fully protected against Russian or any other hackers. Underground “hacks” for sale allow remote attackers to infiltrate phones, especially ones without the latest system updates, as is the case for many Android phones. Creating a more hardened phone network is possible, but that would require issuing secure phones to every official, and providing training and technical support. There is no indication that any of that was done here.

But why bother hacking the system? Anything developed this rapidly that has not been properly stress-tested—and is being used in the wild by thousands of people at the same time—is likely to crash the first time it is deployed. This has happened before, to Orca, Mitt Romney’s Election Day app, which was supposed to help volunteers get voters to the polls, but instead was overwhelmed by traffic and stopped working, leaving thousands of fuming voters without rides. It happened in 2008 to Barack Obama’s app, dubbed Houdini, which also crashed on Election Day. It happened to HealthCare.gov—the website that was launched to help people find coverage under the Affordable Care Act, but that failed so badly, it took a team of people from Silicon Valley who quickly and voluntarily left their much cushier jobs and worked seven-day weeks for months to fix it.

Immediately after it became clear that the Iowa Democratic Party was unable to produce results and, worse, was talking about “inconsistencies” in results, Donald Trump surrogates started talking up how this must have been a fix perpetrated by the Democratic National Committee, perhaps in hopes of riling up supporters of Senator Bernie Sanders who were already suspicious of the party establishment. Some Sanders supporters, wary after a last-minute poll widely expected to show a Sanders surge was scrapped due to errors, needed no such encouragement, and suspected that this was designed to trip up the momentum their candidate expected from his anticipated win. (To which I can only say: The DNC isn’t competent enough to pull off such a plot.) Chaos reigned last night, as campaigns struggled to figure out what to do. Some started hinting that their candidate had won or done very well. Senator Amy Klobuchar showed real political talent and quickly gave a cheery “we outperformed expectations” victory speech early in the night. Being out in front of the other candidates gave her a chance to demonstrate a calm demeanor to a national audience. Other campaigns quickly followed suit, giving hasty overlapping speeches. The campaign of former Vice President Joe Biden, who seems to have performed poorly, has lawyered up. (Biden may want the Iowa results to remain questionable until he can get to states where he is expected to perform better.) The result of this collective chaos will be more mistrust at a time when mistrust in America’s political system is rampant.

There never should have been an app. There are officials responsible for precinct results, but there are also representatives of campaigns on the ground in every precinct. Even without a more substantial reform of the complex and demanding caucus process, a simple adversarial confirmation system (a process used by many countries) would have worked well.

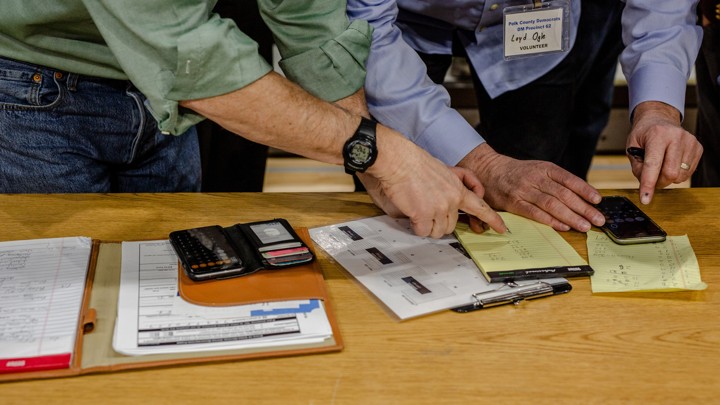

Here’s how it might go: Once the results are known in each precinct, representatives designated by the campaigns get together and sign copies of the results. Each campaign gets a copy of the results signed by everyone else, as does the precinct official. The official phones in the results and texts a photo to a designated number. The integrity is guaranteed by the fact that every campaign can also tally its own results, tracking official precinct announcements as they come in. Such a system would be immensely difficult to meddle with at scale, as designated representatives from every campaign (who are adversarial and have no incentive to cooperate) would have to fully collude and keep it all secret at thousands of locations, under the watchful eyes of the citizens there. Everything is checked twice, and no paper trail is discarded until the results are finalized. Results would be known within the hour, with very little reason to worry about hacking or meddling.

America already knows how to do election integrity. The National Academy of Sciences released a lengthy report about it last year, complete with evidence-based recommendations for every step of the electoral process. I wrote a summary of that report, but the full thing is available online. It tells us why optical paper-scan systems offer us the best mix of convenience and security, and advises us how to keep a proper paper trail. Experts and civil-society organizations have been advocating for these changes for years. It would take just a bit of money and political will to fix much of this, and fairly quickly. Instead, we’ve kicked off a 2020 election season that promises to be fraught in any number of ways. Several campaigns have reported that the same app is due to be used in Nevada in just three weeks.

No comments:

Post a Comment