By: Sagatom Saha

Editor’s Note: This is the second part of a two-part article that addresses the ways in which the evolution of China’s internationally-focused economic policies are likely to impact—and in many instances, to clash with—the economic policies and interests of the United States. The first part, which appeared in our previous issue (The Future of Chinese Foreign Economic Policy Will Challenge U.S. Interests, Part 1: The Belt-and-Road Initiative and the Middle Income Trap, January 29), discussed two primary issues: the policies surrounding the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s worldwide program of infrastructure construction; and the policies that Chinese leaders are likely to adopt as they seek to avoid the “middle-income trap” of stagnating economic growth. This second part examines China’s efforts to advance usage of the renminbi as an international currency, and to seek a greater role in economic institutions traditionally led by the United States and its European allies.

Introduction: China’s Economic Progress—and Lack of International Influence

Complications surrounding the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and the dangers of the “middle-income trap,” are not the only factors impacting the international economic policies of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Furthermore, poor capital efficiency is not the only feature of the Chinese economy that frustrates the country’s policymakers. China’s gross domestic product (GDP) has roughly doubled in the last decade, but Beijing’s pull in the international monetary and financial system remains lackluster. This lack of progress stems in part from the dollar’s centrality around the world, as well as U.S. dominance in international economic institutions. Beijing’s economic planners have long advocated against the dollar while attempting to increase the global role of the PRC’s own renminbi (RMB) currency. While past efforts stumbled, RMB internationalization and increased Chinese influence will directly confront U.S. economic and geopolitical interests.

Renminbi Internationalization

First, Beijing intends to displace the dollar as the dominant international currency and inherit the longstanding advantages the United States has long enjoyed. The United States benefits from low borrowing costs because of high global dollar demand, and U.S. returns on overseas investments outpace interest on U.S. debt by roughly 1 percent annually.[1] Further, internationalizing one’s own currency makes trade cheaper by lowering hedging and transaction costs. In contrast, China’s dollar-denominated contracts create exchange rate risk, which China manages at the expense of monetary policy autonomy. China is particularly exposed to exchange rate risk as the world’s largest importer of oil, which is a dollar-denominated commodity (EIA, February 5, 2018). Most importantly, the dominant dollar confers influence in international institutions, which China lacks despite its economic size. [2] Further, Washington can enact potent sanctions because of the dollar’s central role in the global banking system, and Beijing sees itself as a potential sanctions target (SCMP, April 16, 2018). Overall, internationalizing the RMB would increase Chinese capital efficiency by lowering RMB-associated costs and giving Beijing a powerful tool in the global monetary and financial system.

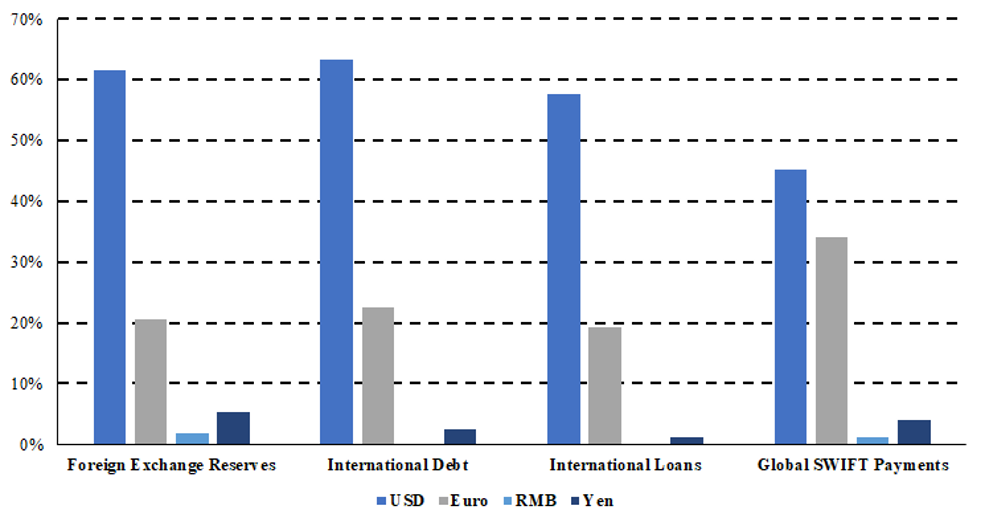

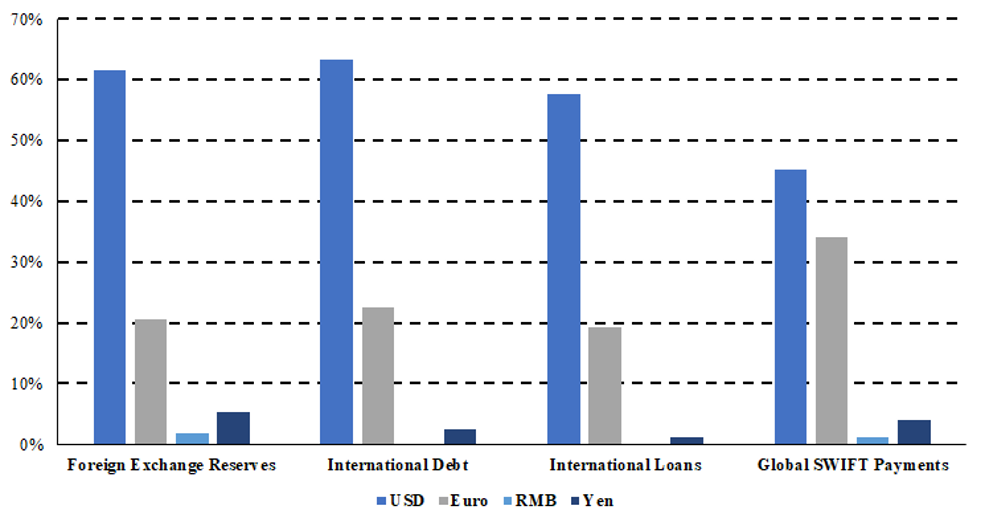

China has attempted to internationalize the RMB by gradually liberalizing its capital accounts, but to little avail. In 2016, China scored a long-desired win when the International Monetary Fund (IMF) included the RMB in its Special Drawing Rights (SDR)—an asset built from a basket of currencies, which is intended to help countries diversify their reserves (IMF, March 4, 2016). Nevertheless, even optimistic scenarios see the RMB making up no more than 4.5 percent of global reserves by 2025, below where the Japanese yen stands today (MarketWatch, January 17, 2018). No other currency, including the RMB, is close to the dollar’s dominance in foreign exchange reserves, international lending, and global payments (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Snapshot of the International Financial and Monetary System

China still lacks free capital flows. Beijing has made some moves in the past to widen the band that the RMB floats in, to sell RMB-denominated offshore bonds, and to allow some cross-border trade in RMB. Despite these limited steps, the government still controls most cross-border capital flows, and the trade war has forced Beijing to tighten its grip. The issue of RMB internationalization did not feature in the 19th Party Congress, which in 2017 set the national political agenda for the next five years. Beijing instead shifted focus to preventing capital flight and bolstering currency stability, at the expense of RMB internationalization. [3] RMB internationalization has taken a backseat for the time being—but the trade war cannot last forever, especially if the United States and China finalize an interim trade deal.

Global confidence in the U.S. dollar is not guaranteed. The overuse of sanctions by the United States already irritates U.S. allies and adversaries alike. Continued heavy use of sanctions could push both groups together in questioning the wisdom of the dollar’s centrality. In 2018 Russia, one of the world’s largest holders of foreign exchange reserves, decided in the face of U.S. sanctions to dump $100 billion worth of dollar-denominated reserves, replacing them with Euro and RMB (Bloomberg, January 9, 2019). Sanctions have also unsettled some aspects of the transatlantic relationship: partially as a result of the U.S. sanctions regime against Iran, European central bankers in 2018 began replacing dollars with RMB in their reserves (Quartz, January 16, 2018).

Moreover, the U.S. faces debt-ceiling crises that continually risk, at best, lapses in U.S. debt payments—and defaults, at worst. A U.S. default could result in a credit rating downgrade, which would push investors and central banks to search for new sources of stability. In 2016, President Trump even suggested that the United States should strategically default (before walking his comments back later). Congress in July 2019 lifted the debt ceiling for two years, but the same underlying political dynamics remain. U.S. debt default is unlikely but certainly not impossible, and Beijing would benefit if it were to occur. [4]

China’s trade surplus makes it difficult for Beijing to get large amounts of RMB into global circulation. However, that situation could change if the Chinese current account falls into deficit (Morgan Stanley, March 13, 2019). BRI could also serve as a vehicle to circulate Chinese currency abroad with RMB-denominated loans. The dollar has never faced a challenger like the RMB before. Investors and central banks lost confidence in the Euro—the only serious competitor the dollar faced—after the Eurozone Crisis left them uncertain whether the currency would survive, let alone how many countries would continue using it. That uncertainty persists today. Yen internationalization faced resistance from Japanese financial institutions and its business community, which have profited from currency hedging and denominated sales in dollars, given that the United States remained Japan’s premier export market (Foreign Affairs, January 1, 2018). In contrast, Chairman Xi’s brand of authoritarian capitalism is well-suited to avoid these issues.

The RMB faces a narrow path in displacing the dollar, but Beijing could find a way to loosen capital controls without foregoing state-managed capitalism and industrial policies, especially if nationalists advocating China’s global prestige and financial reformers both rally around the project. Washington should expect Beijing to pivot back to RMB internationalization once trade matters are settled. An international RMB would directly supplant the benefits that the dominant dollar yields to the United States. U.S. officials would not take RMB internationalization lightly if it gained momentum. Image: Zhou Xiaochuan, then-Governor of the People’s Bank of China, holds a discussion with IMF Managing Director Christine LaGarde following a lecture that Zhou presented to the IMF, June 24, 2016. (Source: IMF)

Image: Zhou Xiaochuan, then-Governor of the People’s Bank of China, holds a discussion with IMF Managing Director Christine LaGarde following a lecture that Zhou presented to the IMF, June 24, 2016. (Source: IMF)

Image: Zhou Xiaochuan, then-Governor of the People’s Bank of China, holds a discussion with IMF Managing Director Christine LaGarde following a lecture that Zhou presented to the IMF, June 24, 2016. (Source: IMF)

Image: Zhou Xiaochuan, then-Governor of the People’s Bank of China, holds a discussion with IMF Managing Director Christine LaGarde following a lecture that Zhou presented to the IMF, June 24, 2016. (Source: IMF)

International Institutions

RMB internationalization would also boost China’s global economic influence—in a way that trade and foreign investment have not—by bolstering Beijing’s case for greater sway at the World Bank and IMF. Chinese policymakers, such as former Governor of the People’s Bank of China Zhou Xiaochuan (周小川), have long criticized the Fund and the Bank as crisis-prone because of their reliance on the dollar (BIS, March 23, 2009). These Bretton-Woods institutions offer potent foreign policy tools to Washington, which Beijing hopes to inherit. The IMF allows its leaders to institutionalize desired financial and monetary policies, and to induce cash-strapped countries to adopt them. The World Bank similarly allows the United States to shape norms for global development assistance and prioritize certain projects. For example, World Bank loans disburse faster to countries that align closely with U.S. interests at the United Nations (UN). Even Japan, nearly one-third the economic size of China, has successfully leveraged leadership within multilateral institutions into strategic gains in ways that China has not. [5]

In contrast, China’s status as the world’s second-largest economy, and largest trading partner for much of the world, has not translated into influence within these institutions. China’s vote shares stand at roughly one-third that of the United States within both institutions, lagging far behind its economic size (IMF, February 7; World Bank, undated). Beijing ironically has found it easier to gain influence at the World Trade Organization and the UN, in which economic power does not translate into direct control. In addition to sitting on the Security Council, Beijing benefits from the UN’s “one country, one vote” system, which allows it to exchange foreign aid for support in its efforts to elect Chinese officials to the top posts within the UN’s standards-setting specialized agencies (Foreign Policy, September 24, 2019).

Similarly, the United States is bound to the same slow-moving arbitration system under the WTO as any other country, including China, even though it wins most of its cases (PIIE, November 22, 2019). However, the IMF and World Bank function differently. The United States retains veto powers in both institutions, a benefit no other country enjoys (World Bank, February 10, 2017; Congressional Research Service, August 30, 2019). The PRC leadership has pushed the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and BRI as an alternative to the World Bank, but Beijing would undoubtedly prefer to influence the bank’s loan disbursements and development standards. The IMF still faces little competition as a lender of last resort and standard-setter for global monetary policy, despite its unpopularity among developing countries.

Beijing gained some vote shares after the global financial crisis, but the increase was largely symbolic as it did not erode U.S. veto power. RMB internationalization strengthens Beijing’s bid for increased influence at the Bretton-Woods institutions. Washington could encounter escalating pushback against its veto powers if the RMB displaced the dollar’s dominance in global payments, lending, and reserves. While Beijing’s abuse of WTO rules led to the current trade war, increased Chinese sway at the World Bank and IMF would be far more contrary to U.S. interests. Past negotiations suggest that Washington is unwilling to meaningfully reform the international monetary system. If RMB internationalization parlays into influence with global economic institutions, it would threaten not only the direct benefits the United States enjoys (such as low borrowing costs), but also the ability to oversee multilateral development assistance and global monetary norms.

Conclusion: A Likely Future of Sharpened U.S.-China Economic Tensions

Few matters of foreign policy draw bipartisan consensus, but the need to forcefully tackle China is one exception. Ironically, the export-led model that until recently fueled Chinese economic growth was far more compatible with U.S. foreign policy: it facilitated cheap manufactured-goods imports and low U.S. borrowing costs through China’s massive accumulation of dollars in its foreign reserves. Beijing’s new foreign economic policies will entrench widespread opposition to China within U.S. policymaking circles. China need not fully transition to a market economy to avoid collision with the United States, but Beijing’s current trajectory falls on the wrong side of U.S. interests. Beijing’s charted path portends sustained U.S.-China tensions for the foreseeable future.

Sagatom Saha is an independent energy policy analyst based in Washington, D.C. His writing has appeared in Foreign Policy, Foreign Affairs, Defense One, Fortune, Scientific American, and other publications. He is on Twitter @sagatomsaha.

No comments:

Post a Comment