Dr. Mohammed Cherkaoui

During the month of January 2020, most world capitals, diplomats, and think tanks sought to evaluate the status of the already-fragile balance of power in the Gulf. The U.S. President Donald Trump’s decision to assassinate the Iranian general Qassem Soleimani in Baghdad has triggered the most acute escalation between Washington and Tehran since 1979. The White House’s pursuit of neutralizing the second most important figure in Iran, after the spiritual leader Ayatollah Khamenei, has shifted the US-Iranian rivalry into a fierce confrontation between Washington’s “maximum pressure” and Tehran’s “maximum resistance”. There have been several interpretations and predictions of Iran’s possible direct or indirect acts of retaliation vis-à-vis Trump’s threats of targeting 52 sites, which have political and cultural significance for the Iranians.

Some Washington-based analysts have been wary that “the U.S. and Iran are now in a traditional escalatory slope, and although neither side wants war, there is a real risk that it might happen.”(1) Anthony H. Cordesman, leading analyst at Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, has cautioned that the new US-Iran crisis “has now led to consistent failures in the U.S. strategy when dealing with Iraq and the Middle East for the last two decades – and has already turned two apparent ‘victories’ into real world defeats.”(2)

In Doha, two research institutions, Aljazeera Centre for Studies and Qatar University’s Gulf Studies Centre, hosted a two-day conference, “Toward a New Gulf Security Order: Abandoning Zero-sum Approaches” at Qatar University January 19 and 20, to formulate new perspectives of the waning regional security order, and explore how to construct an alternative paradigm. As a point of entry, the Conference concept highlighted two manifestations of the failure of the existing security order, formally adopted by all Gulf States, since the establishment of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) May 25, 1981: First, to prevent the invasion, and later liberation, of Kuwait in the early 1990s. GCC established a coalition land force, “the Peninsular Shield Force”, with the objective of defending the six nation states, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Second, the decision of three member states - Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain - to impose a blockade on Qatar, a founding member of GCC since June 2017.(3)

In this turbulent part of the world, Iran’s pursuit of creating a regional security order, but on the parsuit of the withdrawal of U.S. troops from the region—a condition rejected by Gulf states, which see the United States as the principal guarantor of their national security. Moreover, Iran still considers its own foreign interventions in the Gulf and Arab region as part of its revolutionary identity, to which it has devoted resources and agencies.(4) This paper “Seven Ironies of Reconstructing a New Security Paradigm in the Gulf” is a summary of the presentation I delivered at the Conference’s fifth panel “The Gulf and the US-Gulf Conflict”. It probes into several challenges of deconstructing the status quo, before envisioning an alternative framework of mutual security cooperation among several actors in the Gulf and the Middle East.

There has been a correlation between the transformative Gulf security arrangements and the US strategic interests in the region. For instance in the late 1970s, then-US president Jimmy Carter told Congress an attempt by any outside force to gain control of the Gulf region “will be regarded as an assault on the vital interests of the United States of America, and such an assault will be repelled by any means necessary, including military force.”(5) Since 1984, The GCC member states have renewed their collective security mechanism at several intervals. For example in early 2000, they signed a “joint defense pact”, whose details were not publicly released. Still, the GCC members pledged to increase the existing Peninsula Shield Force from 5,000 to 25,000, and develop a shared early warning system; and that the pact’s language states, “An attack on one member is an attack on all GCC states.”(6)

The scope of the Gulf security, its military prerequisites, and the super powers’ role have been a debatable issue between Gulf and Western capitals. Sheikh bin Jassim bin Jabr al-Thani, then-foreign minister of Qatar, stated in an off-the-record session of The Washington Institute's Policy Forum, in January 1994, “The Gulf countries' level of armaments ought to be determined by their defensive needs. When one nation expands its military capabilities beyond its defensive requirements, it diminishes regional security as a whole. The driving principle behind regional security for both large and small nations in the Gulf should be mutual cooperation and respect for each nation's sovereignty and culture.”(7)

At the turn of the new century, the GCC military pact represented the highest level of grouping between the six nations with similar strategic nuances of its trajectory. Several observers expressed optimism about the Peninsula Shield Force as a potential nucleus of a grandiose Gulf security mechanism. For instance, Ray Takeyh and Steven Cook advocated the idea of building a new security network that “could evolve gradually, beginning with confidence-building measures and arms-control compacts and, eventually, lead to a full security system that resembles institutions such as the Organization for Security Cooperation in Europe [OSCE].”(8)

However, the renewed Arab uprisings between 2011 and 2019 as well as the embargo of Qatar in mid-2017 have curtailed the hopes of inclusive security cooperation. They have also contested most of the presumptions of ‘collective security’. Security studies scholars have maintained, “In the most prolific example of a collective security arrangement, nations send their forces to defend or liberate an invaded nation, in situations where they normally would have acted in their own national interest.” (9) Trump’s tendency towards political isolationism and economic nationalism have contested such a deep involvement in securing or defending the Gulf states. He deplored the cost of the US military presence in the region; “I say it so much and it’s so sad, but we have $7 trillion in the Middle East. You might as well throw it out the window. Seven trillion dollars.” (10) This US expenditure on its military presence in the region represents less than 1 percent of the 2019 budget of the Pentagon.

By 2020, the Gulf security has reached a stage of nihilism of any current Gulf doctrine, and has implied emerging concerns among a divergence of existentialism between two-camps: the Saudi-UAE-Bahraini offensive camp versus the Qatar-Kuwait-Oman resilience camp, which is aware of their status as small states. In a nervous post-Soleimani assassination Gulf, a number of political ironies have come to the surface.

1. The From-back-to Dilemma of Zero-sum Approaches

The AJCS-Qatar University Conference opted for probing into possible approaches to depart from the de facto zero-sum assumptions in addressing emerging dynamics in the region in 2020 and beyond. It affirmed the rejection of the status quo; “the failure of prevailing security approaches and the persistence and exacerbation of conflicts make it urgent to find new security approaches that can meet existing threats and prevent or preempt nascent ones. This system should accommodate the concerns and interests of Gulf states - perhaps security orders with proven effectiveness, such as the European order, can be a guide - while also allowing for the differences between the two regions and political and ideological particularities.” (11)

However, most analysts including the panelists at the Conference still rely on several frameworks and assumptions of International Relations (IR), namely Offensive and Defensive Realism theories and Balance of Power theory, as shaped by Herbert Butterfield, John Herz, and Robert Jervis, more that the propositions of Strategic Studies or Conflict Resolution. Most panelists explained how Arab and Persian Gulf states seek “not to maximize power but to maintain their position in the system,” as leading realism theorist Kenneth Waltz would argue.(12) It was not expected to witness such a U-turn to political realism. The security dilemma remains the theoretical linchpin of defensive realism, and “makes possible genuine cooperation between states—beyond a fleeting alliance in the face of a common foe.”(13) There is also the factor of uncertainty in conjunction with the fluidity of the current situation.

Robert Jervis, one of the IR most celebrated theorists, defines the security dilemma as “the unintended and undesired consequences of actions meant to be defensive.”(14) Herbert Butterflied has proposed six propositions: 1) its ultimate source is fear, which is derived from the “universal sin of humanity”; 2) it requires uncertainty over others' intentions; 3) it is unintentional in origin; 4) it produces tragic results; 5) it can be exacerbated by psychological factors; and 6) it is the fundamental cause of all human conflicts. (15)

There was also dominant advocacy of the need for integrating hard security and soft security, including military technology and efficient tools of combatting cyber terrorism. This is not an easy task now for local policy makers in the Gulf. As a result, the perceived threats, real or imagined, have barricaded the search for alternative approaches under the weight of those realist conceptualizations.

US aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln in the Arabian Sea, 7 June (Reuters)

US aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln in the Arabian Sea, 7 June (Reuters)

Inside the Beltway in Washington, most interlocutors and analysts have internalized a similar power-driven realist framework of analysis. For example, Ilan Goldenberg of the Center for a New American Security points out, “On the one hand, they are happy that Trump is willing to sanction and pressure and take Iran down a notch. But, on the other, They are nervous that he is unsteady and goes too far… No one really knows what Donald Trump will do.”(16) This is an open-ended query with several options of the US-Iran standoff. The parallel semi-militaristic media coverage in the United States and the Gulf has also deepened a groupthink-like dilemma, which still pivots around the very zero-sum framework. Any possible retaliation of Iran or its non-state actors allies, such as Hezbollah, remains a point of reference in predicting the future of the region. This is a pattern of recycling the zero-sum approaches par excellence.

2. Caught up in a Web of Foreign Military Bases

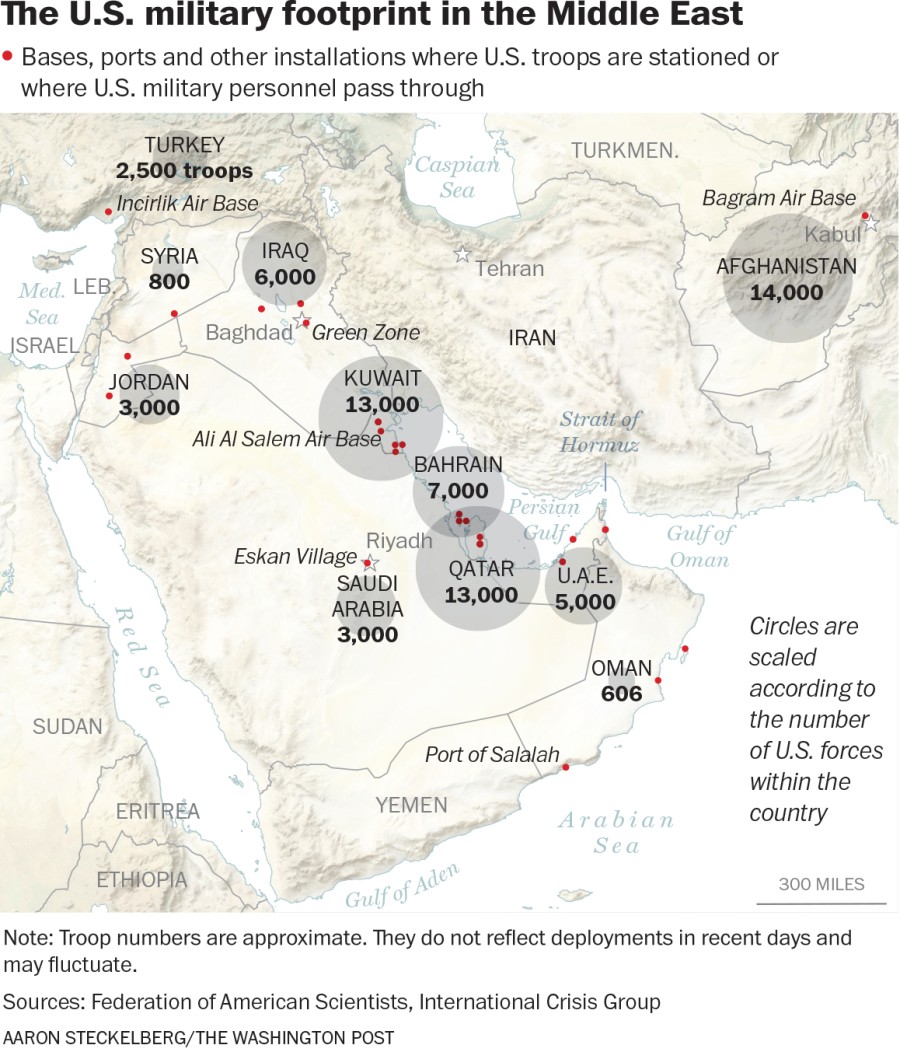

To design an alternative Gulf security framework would not occur in a vacuum, rather in the strategic setting shaped by the will of several powers through their mushrooming military bases in the region. There has been heavy militarization of the region with some 50 foreign bases including US, British, French, Italian, and most recently Chinese troops stationed in Djibouti. Twelve Arab countries such as UAE, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Bahrain, and Egypt host those foreign military bases. China has been steadily building its footprint in the region whereas Trump’s America has considered ways extricate itself from “forever wars” in the Middle East.

According to the most recent estimates of the Washington Post, about 14,000 US troops are deployed in Afghanistan, 13,000 in Kuwait, 13,000 in Qatar, 7000 in Bahrain, 6,000 in Iraq, 5000 in UAE, 3000 in Saudi Arabia, 3000 in Jordan, 2500 in Turkey, 800 in Syria, and around 600 in Oman.(17) In early January 2020, the Pentagon announced an additional 3,500 troops to the region, while troops in Italy were put on standby, according to defense officials in Washington.

The US presence remains a key factor in harmonizing the strategic competition over the Gulf. A recent Chatam House study has pointed out “the US has substantial influence in the Middle East and can project military power quickly. However, working with partners whose interests sometimes conflict with one another has occasionally harmed long-term US objectives.”(18) Despite Trump’s intention of political isolationism and military withdrawal, the Pentagon officials struggle to explain plans for Middle East deployments. Undersecretary of Defense for Policy John Rood has told the Senate Armed Services Committee “The secretary of Defense is consistently, and continues to evaluate, with the advice of others, what the appropriate number of forces to be deployed to the Middle East is… As necessary, the secretary of Defense has told me he intends to make changes to our force posture there.”(19)

The Gulf region has turned into a wait-and-see moment, while being frozen in an unsecure and suspicious mood. It is also a political jeopardy under the deepening US-Iranian cold war after the assassination of Soleimani. In their attempt to imagine a ‘new security order’ in the Gulf, Frederic Wehrey and Richard Sokolsky wrote, “At the heart of the current dilemma is a clash of visions between the two sides of the Gulf littoral: Iran seeks the departure of U.S. forces so it can exert what it regards as its rightful authority over the region. Meanwhile, the Gulf Arab states desire a continued American presence to balance what they see as Iran’s historical ambition of hegemony.”(20)

3. Dragonbear: A New Russian-Chinese Pendulum of Gulf Security

Following the attacks on one Saudi, one Norwegian, and four Emirati oil tankers near Fujairah emirate, outside the Strait of Hormuz in May 2019, Russia sought to capitalize on the fear factor and to reposition the security prerequisites in the region. In a letter to the UN Security Council and the UN General Assembly July 23, 2019, the Russian Mission presented what it termed “Russia’s Security Concept for the Gulf Area” as a ‘collective’ plan of action. Russia has argued that the idea of establishing a security system in the Gulf area “might be essential for consolidating political and diplomatic efforts in this region. It implies a long-term programme of action aimed at normalizing the situation, improving stability and security, resolving conflicts, identifying key benchmarks and parameters for a future post-crisis architecture, as well as ways to fulfill the related tasks.”(21) Accordingly, Moscow’s concept derives from several principles:

Consolidating, in a single counter-terrorism coalition, all stakeholders interested in eliminating the hotbed of extremism and terrorism in the Middle East and ensuring sustainable political settlement in Syria, Yemen, other countries of the region, is a priority.

There is a need for mobilizing public opinion across Islamic and other countries with a view to jointly countering the threat of terrorism, including through integrated efforts in media space.

All parties should adhere to international law, to the UN Charter and UN Security Council resolutions in the first place.

Peace-making operations can only be conducted on the basis of relevant resolutions of the UN Security Council or upon request of the legitimate authorities of the attacked state.

The security system in the Gulf area should be universal and comprehensive; it should be based on respect for the interests of all regional and other parties involved, in all spheres of security, including its military, economic and energy dimensions.

Multilateralism is considered to be a mechanism of participation of stakeholders in the joint assessment of the situation, decision-making process and implementation of decisions. Exclusion of any stakeholder for any reason is inadmissible.

Progress toward the establishment of a security system should be achieved on a step-by-step basis starting with most relevant and urgent problems. These concerns, first and foremost, combat against international terrorism, the settlement of the Iraqi, Yemeni and Syrian crises, and the implementation of all agreements reached on the Iranian nuclear programme.

This step-by-step approach is also applicable to the adoption by the Gulf states and international community of confidence-building measures and provision of mutual security guarantees in the region.

The establishment of a security system in the Gulf area is considered as part of the solution aimed at ensuring security in the Middle East as a whole. In this context, the principles of respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, settlement of issues of domestic politics through national dialogue, within the constitutional framework and without external interference, are crucial.(22)

Russia's Special Presidential Representative for the Middle East and Africa and Deputy Foreign Minister Mikhail Bogdanov present Russia’s Collective Security Concept for the Gulf Region

Russia's Special Presidential Representative for the Middle East and Africa and Deputy Foreign Minister Mikhail Bogdanov present Russia’s Collective Security Concept for the Gulf Region

These are new diplomatic variables at the United Nations designed to be political overtures with the Gulf capitals. Some analysts have perceived the Russian plan as “a radical overhaul of the security architecture in the area, which is home to massive oil and gas reserves and some of the world’s most strategic waterways.” (23) Three months later, China decided to support the Russian plan, and maximize its potential in replacing the Gulf’s US defense umbrella, and position Russia as “a power broker alongside the US”, and comes amid heightened tensions as a result of “tit-for-tat tanker seizures and a beefed-up US and British military presence in Gulf waters.”(24)

Velina Tchakarova of the Austrian Institute for European and Security Policy (AIES) in Vienna went back to her conceptualization of ‘Dragonbear’, which she coined in 2015 to describe the probability of an emergence of a highest-ranking systemic relationship and comprehensive rapprochement between China and Russia in various key fields, captures once again this Russian-Chinese strategy. As she explains, “The Dragonbear is neither an alliance nor a marriage of convenience, but rather a temporary asymmetric relationship, in which China is predominantly the agenda-maker, while Russia is mostly the agenda-taker. So long as the Dragonbear shares the common interest in opposing the US in every possible field, the systemic coordination of actions and measures between China and Russia will continue despite emerging bottom-up tensions in areas of intersection of their national interests.(25)

Harvard IR scholar Stephen Walt once said, “Instead of asking why Russia and China are collaborating, or pondering what has brought Iran together with its various Middle East partners, they assume it is the result of shared authoritarianism, reflexive anti-Americanism, or some other form of ideological solidarity. This act of collective amnesia encourages U.S. leaders to act in ways that unwittingly push foes closer together, and to miss promising opportunities to drive them apart.”(26)

Those diplomatic maneuverings at the UN and between Moscow and Beijing imply a silent shift from the Americanization to the internationalization of Gulf security in 2020 and beyond. They also raise the question whether there is organic concept or blueprint of a Gulf security paradigm built from within and according to local measures and nuances. Anthony Cordesman has highlighted the correlation between the failure of America’s Strategy in the Middle East and the loss of Iraq and the Gulf. My question, which begs for an immediate answer, is there a strategic Gulf/Arab mind capable exiting the US security trusteeship, or protectorate; and suppressing the emerging Russian, Chinese, and likewise plans of control. Such a strategic Gulf/Arab mind is required to shift from a typical reactive mode, as it has been the case since Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990, the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, and the Quartet’s blockade if Qatar in 2017.

U.S. Navy Vice Adm. James Malloy speaks during the International Maritime Security Construct opening ceremony in Manama, Bahrain, on Nov. 7, 2019 (Getty)

U.S. Navy Vice Adm. James Malloy speaks during the International Maritime Security Construct opening ceremony in Manama, Bahrain, on Nov. 7, 2019 (Getty)

The current situation in the region calls for a pro-active and critical-thinking approach to designing an avant-garde formula for the protection the Gulf and its oil and gas resources. It also warrants an early warning system outside the scope of the US, British, Russian, or Chinese guardianship, through the development of an inside-out vision of assessing existing threats and formulating adequate strategies of prevention and containment. The design of any alternative security paradigm should depart from the competition of the five main strategies of the United Sates, Israel, Russia, Iran, and Turkey. What is unfortunate is that most of the Gulf states have alienated themselves with one of those nexuses with varied dimensions of dependency.

4. Security of One Gulf or Multiple Gulfs?

Since the summer of 2017, there have two interpretations of the Gulf security: one normative that presupposes the Qatar question is a political haphazard that can be fixed soon, while the GCC remains intact. The other interpretation is real in detecting the depth of the Gulf fragmentation, not into two Gulfs: one Arab versus one Persian. From a conflict analysis perspective, I argue there are three Gulfs with different trajectories; one defensive Gulf including Qatar, Kuwait, and Oman; one offensive Gulf, which has regrouped Bahrain, UAE and Saudi Arabia, and one Persian Gulf with a mixed strategy of repositioning Iran, as a force of resilience against America’s position and a source influence vis-à-vis the Arab neighbors.

Iran has acted as the custodian of the Gulf security, and has turned the attacks on the oil tankers in 2019 into an opportunity of realist nationalism. Ali Shamkhani the secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council stated, “We have always said we guarantee the security of the Persian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz… We repeat our stance and call on U.S. forces to finish their presence in the region as they are the main source of crisis and instability.”(27) By September 2019, President Hassan Rouhani made plans to “present to the world the Hormuz Peace Initiative — the gist of which is love and hope — with the slogan ‘The coalition of hope.’”(28) He also vowed his Armed Forces would stand “by the side of the people of Iraq, Syria, Palestine, and Lebanon”, and asserted, “they brought security to those lands and managed to root out savage terrorists in the region. That is how we are different from the enemy.”(29)

5. Trump’s ‘Strategy’ or Political ‘Miscalculation’?

Trump's statements and the Pentagon’s position on a would-be military withdrawal from the Middle East have become a misnomer in Washington. The decision to eliminate Gen. Soleimani in the mix of several-open crises in Syria, Yemen, Libya, other hot spots leaves Trump’s Middle East strategy in tatters. One of the first tests now is Iraq the United States and Iran will seek to extradite each other from a country, which remains split between Iran’s growing influence and America’s loosening grip. Middle East politics observer Randa Slim notices Iraq is entering 2020 in “a situation it has long sought to avoid: stuck in the middle of an U.S.-Iran military escalation… Regionally, Iraq’s outreach to its Arab Gulf neighbors will also be seriously affected. Arab Gulf countries have been trying to distance themselves from the U.S. decision to kill Soleimani and are increasingly concerned about the lack of a post-kill U.S. strategy and the potential impact from an all-out regional war.” (30)

Trump considers Iraq as the home base for operations against the Islamic State, and insists the U.S. would not leave Iraq unless it gets paid back for the “billions” spent on an air base there. He told reporters on Air Force One “If they do ask us to leave, if we don’t do it in a very friendly basis, we will charge them sanctions like they’ve never seen before ever,” he said. “It’ll make Iranian sanctions look somewhat tame.”(31) His Secretary of State Mike Pompeo feels confident the United States has the upper hand vis-à-vis Iran. He said in a speech at Stanford University the same week, “We now enjoy a great position of strength regarding Iran. It is as good as it has ever been, and Iran has never been in the place that it is today… We have reestablished deterrence, but we know it is not everlasting, that risk remains. We are determined not to lose that deterrence.” (32)

The line remains blurry whether Washington can withdraw, or at least minimize ,its troops in the region or be in need for a redeployment as the map of geopolitical threats shifts from one crisis to another. David Frum a former speech writer at the White House believes “the policy is not working. Yet recurring failure is taken by Pompeo and other Iran hawks as an invitation to keep pressing. Meanwhile, Trump continues to regard Iran policy as an opportunity to extract political and personal advantages for himself.”(33)

In the latest deployment, Washington has sent additional 3,500 troops to Kuwait, and Trump has bolstered American forces by about 17,000 personnel since May 2019, a decision that raises eyebrows about his electoral vow to get the United States out of “endless wars.” As Aaron David Miller, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace asserts “Rarely has any single tactical move, untethered from any long-range thinking, produced so many potential strategically negative consequences for the United States… In one single decision you’ve undermined 17 years of a U.S. mission, fraught though it may be.”

Iraqi Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi in Baghdad as Iraq’s parliament called on U.S. troops to withdraw from the country (Getty)

Iraqi Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi in Baghdad as Iraq’s parliament called on U.S. troops to withdraw from the country (Getty)

6. Gulf Security à la Carte!

Trump maintains his position on avoiding any additional cost, besides the $7 billion already spent in the Middle East. In mid-2019, he signaled his intention not to provide US protection for the Gulf states in the aftermath of the attacks on Saudi and Emirati tankers near the strategic Strait of Hormuz and also against Aramco facilities in Saudi Arabia, saying that US troops do not "even need to be" in the Gulf. He also wrote on Twitter, "Why are we protecting the shipping lanes for other countries (many years) for zero compensation. All of these countries should be protecting their own ships on what has always been a dangerous journey." He made these remarks come a few days after he called off military strikes against Iranian targets amid increased tensions between Washington and Tehran.

Trump has made direct hints to dissolve any US strategic or moral responsibility to protect the Gulf states, and contested any expectation Washington would come to their rescue. As he stated, “All of these countries should be protecting their own ships on what has always been a dangerous journey. We don’t even need to be there in that the U.S. has just become (by far) the largest producer of Energy anywhere in the world! The U.S. request for Iran is very simple - No Nuclear Weapons and No Further Sponsoring of Terror!”(34)

There is growing belief in most Gulf capitals that Trump’s good intentions or promises are short lived. After the assassination of Gen. Soleimani, Saudi deputy defence minister Prince Khalid bin Salman rushed to Washington and London to deliver a message that Riyadh wanted to see a de-escalation of the United States’ struggle with Iran. This response was seen as a sign that Saudi is nervous about its vulnerability to Iranian missile strikes – and still uncertain about the reliability of Trump’s long-term commitment to his Gulf allies. Meanwhile as Patrick Wintour wrote, “global think-tanks are littered with reports setting out the path to a Saudi-Iran rapprochement, and perhaps the best that can be secured in the foreseeable future is a limited non-aggression pact. That would be an advance on all-out war.”(35)

Flight deck of the U.S aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN 72) in Arabian Sea, May 19, 2019 (Reuters)

Flight deck of the U.S aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN 72) in Arabian Sea, May 19, 2019 (Reuters)

In an interview with NBC News the same week, Trump explained he was not looking for war, “if there is, it will be obliteration like you've never seen before.” He also revealed that he called Saudi Arabia's Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, asking him to pay for the "very expensive operation" to protect the Gulf from Iran. As the situation may shift a more escalatory mode later in the year, Gulf capitals may find themselves in an unusual setting of negotiations with the White House over the requested financial cost toward a US per-piecemeal protection. Trump will usher them to his well-packaged menu to select what need they need and for what price they can afford. Welcome to a new age of Trumpian shopping mall for security services!

7. End of “Gulf Exceptionalism” in US Politics

After establishing full diplomatic relations between Washington and Riyadh under the Mutual Defense Assistance Agreement signed in 1951, Saudi Arabia has positioned itself as ‘special state’ with some ‘deep influence’ in US politics, especially with the Republican Party. Its source of influence derived from America’s need for oil. The bilateral relations have benefited from an exchange of Saudi oil for American security, and encompassed economic, political, and military spheres. However, Trump’s presidency has pushed those relations into a forced realignment.

In recent years, the United Arab Emirates has sought to come closer to the Saudi clout in Washington with its willingness to pour astronomical sums of money into improving its public standing in the United States. UAE has made sizeable donations to a wide range of think tanks and policy centers, including the Center for American Progress, the Aspen Institute, the East West Institute, the Center for Strategic and International Studies, and the Middle East Institute in Washington.

Emirati ambassador Yousef Al Otaiba, once described as “the most charming man in Washington” has brought his country to the limelight of Washington and promoted the MBZ-MBS connection. He has also triggered some comparison between his skills and those of Prince Bandar bin Sultan, who reigned as Saudi Arabia's ambassador to Washington for decades, forging a bond between Gulf and Washington elites.(36) Matt Spence, who was the top Defense Department adviser on Middle East policy, explained, “He's been remarkably effective for two reasons: it's clear he's speaking on behalf of the government when he's talking and he's very accessible.”(37)

Still, the US-Gulf relations are now on a shaky foundation under Trump’s presidency. He has reversed two historic trends: his withdrawal from any commitment to provide security, unless for a high price, and his rejection of US addiction to the Gulf oil. During the heightened tensions with Iran, Trump stated, "We are independent, and we do not need Middle East oil.” Indicators have shown a sharp decrease of Gulf oil impost to the United States, which bought 56771 barrels in 1994, 63490 barrels in 2000 before lowering to 22965 barrels in 2020. As the Trump White House has opted for those two ‘no-security’ and ‘less-Gulf oil export’ strategies, the U.S.-Gulf relations seem to be shifting into an unprecedented era of trust deficit and end of Gulf exceptionalism in Washington.

No comments:

Post a Comment