Clifton Parker

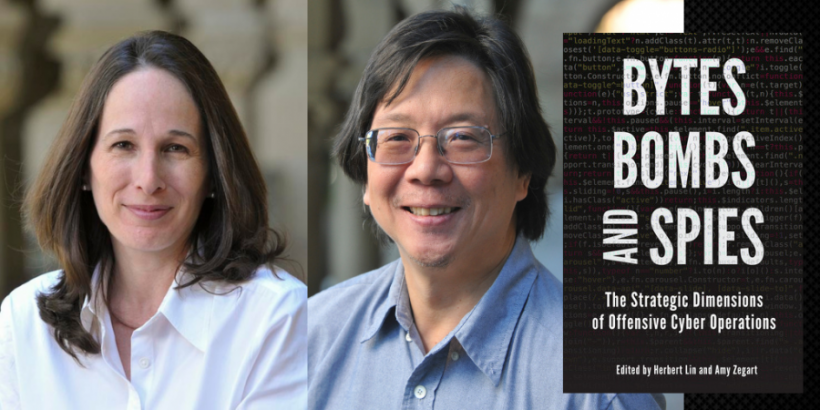

When and how that’s done is the subject of a new book, Bytes, Bombs and Spies: The Strategic Dimensions of Offensive Cyber Capabilities, edited by Herb Lin and Amy Zegart at the Center for International Security and Cooperation and the Hoover Institution.

US military doctrine defines offensive cyber operations as operations intended to project power by the application of force in and through cyberspace. This is defined as actions that disrupt or destroy intended targets.

At a time when US cyber policy is taking a new direction, Bytes, Bombs and Spies is one of the first books to examine strategic dimensions of using offensive cyber operations. With chapters by leading scholars, topics include US cyber policy, deterrence and escalation dynamics, among other issues. Many of the experts conclude that research, scholarship, and more open discussion needs to take place on the topics and concerns involved.

Lin and Zegart are senior research scholar and senior fellow, respectively, at Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation. Max Smeets, a CISAC cybersecurity postdoctoral fellow, is also a contributor to the book.

Offensive cyber rising

Examples in recent years of offensive cyber usage include the Stuxnet computer virus that destroyed centrifuges in Iran and slowed that country’s attempt to build a nuclear weapon; cyber weapons employed against ISIS and its network-based command and control systems; and reported cyber incursions against North Korea’s ballistic missiles system that caused launch failures.

“If recent history is any guide, the interest in using offensive cyber operations is likely to grow,” wrote Lin and Zegart.

One key issue is how to best respond to cyberattacks from abroad, such as the 2015 theft of millions of records from the Office of Personnel Management, the 2016 U.S. election hacking, and the 2017 WannaCry ransomware attack that affected computers worldwide, to name but a few. Those incidents have “provided strong signals to policymakers that offensive cyber operations are powerful instruments of statecraft for adversaries as well as for the United States,” Zegart and Lin wrote.

In September 2018, the White House reportedly issued a directive taking a more aggressive posture toward cyber deterrence. This measure allows the military to engage, without a lengthy approval process, in actions that fall below the “use of force” or a level that would cause death, destruction or significant economic effects. Also, US Cyber Command was elevated to an independent unified command, giving it more independence in conducting offensive cyber operations.

These new policy directions make it all the more imperative that offensive cyber weapons be researched, analyzed and better understood, wrote Lin and Zegart.

Conceptual thinking lags

The 438-page Bytes, Bombs and Spies includes 16 chapters by different authors. Topics include the role and nature of military intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance in cyberspace; how should the United States respond if an adversary employs cyberattacks to damage the U.S. homeland or weaken its military capabilities; a strategic assessment of the U.S. Cyber Command vision; and operational considerations for strategic offensive cyber planning; among others.

“Conceptual thinking,” Lin and Zegart noted, lags behind the technical development of cyber weapons. Some issues examined include:

• How might offensive cyber operations be used in coercion or conflict?

• What strategic considerations should guide their development and use?

• What intelligence capabilities are required for cyber weapons to be effective?

• How do escalation dynamics and deterrence work in cyberspace?

• What role does the private sector play?

Scholars at universities and think tanks need to conduct research on such topics, Zegart said. “Independent perspectives contribute to the overall body of useful knowledge on which policymakers can draw.”

In the chapter Lin wrote on “hacking a nation’s missile development program,” he noted that cyber sabotage relies on electronic access to various points in the life cycle of a missile, from its construction to ultimate use.

“For some points, access is really hard to obtain; in other points, it is easier. Access can be technical (what might be obtained by hacking into a network) or human (what might be obtained by bribing or blackmailing a technician into inserting a USB thumb drive),” he said.

One key, Lin said, is the availability of intelligence on the missile and the required infrastructure needed to fabricate, assemble, and launch the missile.

“Precisely targeted offensive cyber operations generally require a great deal of detailed technical information, and such information is usually hard to obtain, especially if the missile program is operated by a closed authoritarian government that does not make available much information on anything,” he said.

Origins in cyber workshop

The idea for Bytes, Bombs and Spies originated from a 2016 research workshop led by Lin and Zegart through the Stanford Cyber Policy Program. That event brought together researchers from academia and think tanks as well as current and former policymakers in the Department of Defense (DoD) and U.S. Cyber Command.

“We organized the workshop for two reasons,” wrote Lin and Zegart. “First, it was already evident then—and is even more so now—that offensive cyber operations were becoming increasingly prominent in U.S. policy and international security more broadly. Second, despite the rising importance of offensive cyber operations, academics and analysts were paying much greater attention to cyber defense than to cyber offense.”

Herb Lin is the Hank J. Holland Fellow in Cyber Policy and Security at the Hoover Institution and senior research scholar for cyber policy and security at the Center for International Security and Cooperation, a center of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies.

Amy Zegart is the Davies Family Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, where she directs the Robert and Marion Oster National Security Affairs Fellows program. She is founder and co-director of the Stanford Cyber Policy Program, and senior fellow at the Center for International Security and Cooperation, a center of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies.

No comments:

Post a Comment