By: Willy Wo-Lap Lam

Introduction

In his telephone conversation with President Trump on February 6, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary Xi Jinping expressed confidence that Beijing can beat the coronavirus outbreak, and asserted that “the fact that China’s economy will be better in the long run will not change.” But at a meeting of the Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC) a few days earlier, Xi expressed fears about the adverse impact that the Wuhan pneumonia epidemic could have on China’s reform and open door policy (RTHK.hk, February 7; HK01.com, February 6; Ming Pao, February 4). Of even greater concern to the CCP leadership, however, is the sustainability of state power and Beijing’s ability to “uphold stability” (维稳, weiwen) in Chinese society. Much of this hinges on the performance of Xi—who is also state president, commander-in-chief of the armed forces, and the “life-long core” of the party leadership. That Beijing has failed to contain the alarming spread of the virus, however, demonstrates that Xi is facing the gravest crisis since he came to power in late 2012.

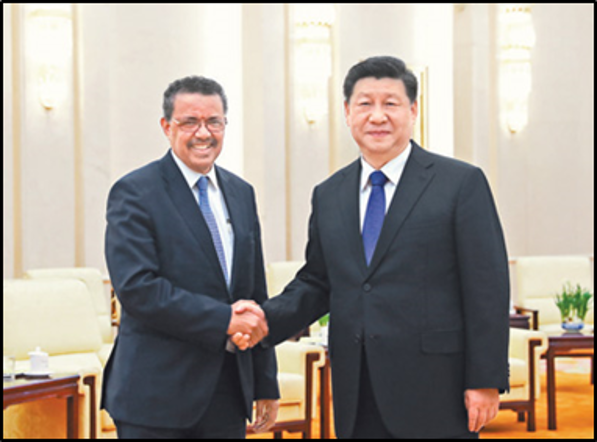

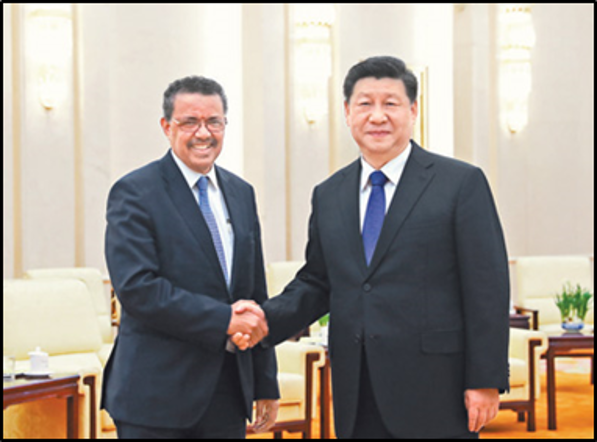

It is clear that Xi is still in solid control of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the People’s Armed Police (PAP), the regular police, and the police state surveillance apparatus. Both central CCP officials and supportive foreign dignitaries are projecting confidence. While visiting Beijing in late January, Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO) Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus praised China’s efforts against the coronavirus disaster, saying that Chinese authorities had displayed “Chinese speed and Chinese efficiency” (People’s Daily, January 29). After an unusual period of public absence in late January and early February, Xi has reappeared to assert his leadership and to declare a “people’s war” against the epidemic (Xinhua, February 11).

Cracks in the CCP Governance Model

Despite such statements, the overwhelming response from officials and commentators around the world is that China’s party-state apparatus seems to lack efficacious means to contain the virus. As a result, Xi’s authority and prestige have taken a body blow. Medicines and medical equipment are in short supply in Hubei and other regions. As of the end of the first week of February, the number of infected patients and deaths had already exceeded those caused by SARS in 2003: by February 11, official figures indicated 42,644 confirmed cases in China and 1,016 fatalities, with most of these occurring in the epidemic’s epicenter of Hubei Province and its capital Wuhan (Radio French International, February 11).

Beijing has not absorbed the lessons of the SARS outbreak in 2003: both Wuhan and Hubei officials, as well as the central CCP authorities, have been accused of understating and misreporting statistics about the number of afflicted persons and fatalities, as well as downplaying the general severity of the situation. For example, a team led by researchers at the University of Hong Kong wrote in the February 1 issue of the British journal Lancet that there were an estimated 75,000 coronavirus victims in Wuhan, a figure much larger than the national toll admitted by Beijing as of early February (South China Morning Post, February 1; Radio French International, February 1; Chinapeace.gov.cn, January 24).

Apart from apparently not divulging the truth to the public and the international community, Xi has allowed traditional factional politics to adversely affect efforts to counter what many have called the first great plague of 21st century. It was not until after Lunar New Year Day (January 25) that Xi set up the Central Leading Small Group to Counter the Coronavirus Epidemic (中央应对新型冠状病毒感染肺炎疫情工作领导小组, Zhongyang Yingdui Xin Guanzhuang Bingdu Ganran Feiyan Yiqing Gongzuo Lingdao Xiaozu) (CLSGCCE). It was announced a day later that Premier Li Keqiang, not Xi, would head up the group (China Brief, February 5).

It seems obvious that if progress is made in containing the SARS-like outbreak, Xi will take credit; however, if the epidemic remains out of control, the responsibility will lie with Li—a long-time political foe of the supreme leader. Moreover, Vice-Premier Sun Chunlan, a Xi protégé, has been dispatched multiple times to Hubei and Wuhan to oversee ground-level operations in her capacity as the leader of a “central government guidance group” (中央指導組, zhongyang zhidao zu) for epidemic control work (Businessinsider.sg, February 8; Xinhua, February 6; CNTV News, January 31; CCTV.com, January 27).

The Personal Position of Xi Jinping

In any event, Xi has made it clear that he alone has the power to oversee the national mobilization against the coronavirus crisis. It was Xi, and not Li Keqiang, who met with visiting WHO Director-General Ghebreyesus in late January. Xi told Ghebreyesus that he had “always been personally in command” and always “personally organizing deployments” in China’s effort to contain the Wuhan disaster (Xinhua, January 28). In a speech given at a PBSC meeting on February 3, Xi praised the work of both Li and Sun—with Sun apparently getting more credit. Thus, Li’s CLSGCCE was cited for “organizing many meetings to study how to deploy work on controlling the epidemic” (多次開會研究部署疫情防控工作, duoci kaihui yanjiu bushu yiqing fangkong gongzuo), while Sun was eulogized for “enthusiastically going about work” (積極開展工作, jiji kaizhan gongzuo) in stemming the outbreak (CNTV Net, February 5; Ming Pao, February 5). Image: CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping meeting with World Health Organization Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus in Beijing, January 28. Xi used the occasion to tell Ghebreyesus that he had “always been personally in command” of efforts to combat the ongoing 2019-nCov virus epidemic. (Source: CCP News, January 29)

Image: CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping meeting with World Health Organization Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus in Beijing, January 28. Xi used the occasion to tell Ghebreyesus that he had “always been personally in command” of efforts to combat the ongoing 2019-nCov virus epidemic. (Source: CCP News, January 29)

Image: CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping meeting with World Health Organization Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus in Beijing, January 28. Xi used the occasion to tell Ghebreyesus that he had “always been personally in command” of efforts to combat the ongoing 2019-nCov virus epidemic. (Source: CCP News, January 29)

Image: CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping meeting with World Health Organization Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus in Beijing, January 28. Xi used the occasion to tell Ghebreyesus that he had “always been personally in command” of efforts to combat the ongoing 2019-nCov virus epidemic. (Source: CCP News, January 29)

Hubei authorities have seemed to give top priority to following the orders of Xi and Sun. Thus, in a provincial party committee meeting, Hubei Party Secretary Jiang Chaoliang said he and his colleagues would “deeply substantiate and materialize” the spirit of Xi’s talks on the epidemic, as well as the “demands made by Vice-Premier Sun Chunlun” while she was inspecting different units in the province. The lack of any mention of Li, who paid a visit to Wuhan in late January, has remained puzzling (Ming Pao, February 6; Xiaoxiang Morning Paper, February 4).

There is also evidence that Xi is taking advantage of national mobilization efforts to double down on the imperative for all aspects of Chinese society to adhere to the zhongyang (中央), or central party authorities—as well as to the position of Xi himself as the “core” (核心, hexin) of that leadership. In the early February PBSC meeting, Xi underscored the imperative of the zhongyang’s “unified directives, unified coordination and unified deployment.” Xi also raised the spirit of the “fourfold consciousness” (四个意识, sige yishi) which includes consciousness of seeing eye to eye with the party’s core. Emphasis was also given to “the twofold safeguard” (两个维护, liangge weihu), which is a reference to safeguarding the authority of the zhongyang and its core (Xinhua, February 4). [1] It is ironic, however, that as of this writing, Xi has not gone on a single inspection trip to disaster zones such as Hubei, Guangdong and Zhejiang Province. The only epidemic-related visit he has made was to the Chaoyang District in the capital (see accompanying image).

The PLA and the People’s Armed Police have played a pivotal role in fighting the epidemic—for example, by distributing medical supplies and even building a brand-new hospital in Wuhan (Xinhua, February 3). These activities illustrate that only one man, Chairman of the Central Military Commission and commander-in-chief Xi Jinping, has the ability to call the shots among the men and women in uniform. In an order to the PLA and PAP on January 29, Xi asked the forces to “take action according to instructions, be brave in taking heavy burden and be daring in fighting the harsh battle.” PLA and PAP forces are instrumental in carrying out the quarantine of Wuhan and other cities. It is also believed that PAP units in particular have been reinforced to “protect” the zhongyang in key cities such as Beijing and Shanghai (Apple Daily, February 6; People’s Daily, January 30; HK01.com, January 29).

Impacts of the Epidemic Crisis on CCP Policy Goals

The epidemic has threatened to dent the ambitions of Xi to secure a legacy as the second-most powerful figure in Chinese Communist Party history. Internally, the Xi administration has boasted about a steady economic growth of at least 6 percent, which it achieved in 2019. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has indicated that it is too early to assess the exact damage that the epidemic will inflict on China’s GDP this year (Straits Times, January 31). The official New Beijing Post cited Xu Gao, a top economist at the Bank of China, as saying that if the epidemic showed signs of receding by February, the crisis would shave merely 0.1 percent to 0.2 percent off this year’s GDP (New Beijing Post, January 30).

However, it seems that Beijing’s financial authorities are less sanguine than official and pro-government economists. The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has injected liquidity into the market to help both giant state-owned enterprise (SOE) conglomerates and small-and medium-sized enterprises. The PBOC said in a public note on February 1 that “a number of policy tools would be used to ensure liquidity in financial markets and prevent volatility in money markets.” Individual banks and financial institutions were encouraged to boost lending to support the real economy, the note added (Deutche Welle Chinese Service, February 3; South China Morning Post, February 1). In general, the optimistic spirit emanating from the Phase One trade agreement with the U.S. on January 15 has been all but dissipated by this plague of the new century.

Xi has also repeatedly made pledges to boost the “patriotic” feelings of Taiwanese and Hong Kong compatriots towards the People’s Republic of China (PRC). However, the results of Taiwan’s January elections (China Brief, January 17) and the anti-Extradition Bill movement in Hong Kong (China Brief, June 26, 2019) have both demonstrated that the majority of Taiwanese and Hong Kong residents resent PRC rule (or the prospect of future rule). Animosity toward time-tested CCP tactics such as suppressing the truth—as demonstrated by the Wunan coronavirus case—has further alienated China from ordinary citizens of Taiwan and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (Theinitium.com [Hong Kong], February 10; HK01.com, January 21).

Conclusion

The Wuhan 2019-nCov virus epidemic, which has hit some 30 countries and regions, has dealt the most severe blow to China’s soft power since the beginning of the Reform and Open Door Policy more than 40 years ago. Through generous loans offered via the Belt and Road Initiative—as well as donations to politicians and academics in wealthy countries—Beijing has bought itself a share of international goodwill over the past several years. However, the coronavirus threat has brought back the specter of the “yellow peril” and the “China threat” (Radio French International Chinese Service, February 5; BBC News Chinese Service, January 30), damaging the PRC’s foreign relations. The potentially precipitous fall in China’s ability to do business with the outside world—coupled with at least short-term cessation of high-level academic and other research projects with leading Western nations—could in turn affect China’s hard power. Supreme leader Xi Jinping is facing his most momentous test since taking power nine years ago.

Dr. Willy Wo-Lap Lam is a Senior Fellow at The Jamestown Foundation and a regular contributor to China Brief. He is an Adjunct Professor at the Center for China Studies, the History Department, and the Master’s Program in Global Political Economy at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He is the author of five books on China, including Chinese Politics in the Era of Xi Jinping (2015). His latest book, The Fight for China’s Future, was released by Routledge Publishing in July 2019.

No comments:

Post a Comment