Wang Xiangwei

Back on January 21 last year, Chinese President Xi Jinping told a gathering of senior officials that they must be on guard against “black swans” and “grey rhinos” which could threaten the rule of the Communist Party amid a slowing economy.

At that time, Xi’s use of animal metaphors sparked discussions among observers who generally interpreted his warnings as being related to different kinds of economic risks. “Black swans” are events that cannot be predicted but have a profound impact on markets, while “grey rhinos” are known risks that have the potential to cause great harm but which people choose to ignore.

One year later, Xi’s wildlife metaphors about the dangers facing the country have proved prophetic on a more literal level.

Scientists and medical experts have pinned down bats as the probable source of the

coronavirus outbreak originating from a wet market which has stalls for trading wildlife animals in Wuhan of Hubei province. The bats are believed to have infected other animals which transmitted the virus to humans.

Medical staff working on the coronavirus outbreak hug each other at the Bingzhou hospital in Shandong province of China. Photo:

Banning the sale of all wild animals is the least of the concerns facing Chinese leaders. How to contain the spread of the coronavirus is their top priority.

There are good reasons why Xi said on Monday that epidemic prevention and control would not only affect people’s lives and health but also China’s social and economic stability and its opening up to the outside world.

In other words, the country’s current public health crisis could threaten the party’s rule and erode the people’s trust in the authoritarian centralised system which the Chinese leaders have been plugging as the be all and end all for building up the country into the second-largest economy in the world.

Xi presided over the Monday meeting of the party’s Politburo Standing Committee, the country’s highest governing council, to discuss the epidemic control and a statement released by Xinhua said the leaders acknowledged the epidemic posed “a major test of China’s system and capacity for governance, and we must sum up the experience and learn from it”.

After a slow start, with mounting evidence pointing to an initial cover-up by the local Hubei provincial and Wuhan city officials along with some national health officials early last month, the Chinese government has since taken increasingly forceful or even draconian measures to contain the spread of the disease. A number of cities in Hubei, including Wuhan – the epicentre of the outbreak which has a population of 10 million – are under lockdown and now an increasing number of cities in other provinces, including Zhejiang, have followed suit.

China scrambles to deliver food to coronavirus epicentre Wuhan amid lockdown

By Friday, the number of confirmed deaths from the virus had risen to at least 636 and the number of confirmed infections stood at more than 30,000, far outpacing the number of infections during the Sars outbreak in 2002 to 2003, which killed nearly 800 worldwide.

While the new virus has spread much more rapidly than Sars, it appears to be less deadly. Compared to a mortality rate of about 10 per cent for Sars patients, about 2 per cent of the people infected with the new coronavirus have died. The latest figures also show that the number of patients recovering from the illness is rising rapidly.

More importantly, as experience from the Sars outbreak shows, the severity and transmissibility of the virus are expected to lessen as the weather gets warmer in the coming months.

But the Chinese government is still facing an epic battle against the spread of the virus in the short term. As the authorities have not fully grasped how the virus is transmitted and have not yet developed vaccines against the disease, encouraging people to stay at home and avoid crowds has become the most effective approach.

But that has proved very difficult as tens of millions of people are expected to return to the major cities after the Lunar New Year holiday, which had already been extended for one week.

In Beijing alone, local officials expect about 8 million residents will have returned to the city between this past week and the next few weeks. Already there have been reports that the returning residents have been barred from their own apartments, causing resentment and anger.

In addition, a shortage of surgical masks and daily necessities such as vegetables and meats in many parts of the county has also caused widespread discontent.

As the government has encouraged people to work from home and factories to delay operations, serious concerns have been raised about the impact on the

Chinese economy and its implications for the global economy. In 2018, China contributed about 28 per cent of the global economic growth, according to official data.

‘Please take my daughter’, pleads mother of cancer patient at coronavirus blockade in China

But the adverse economic impact is mainly to be felt in the first quarter if China’s forceful measures succeed in containing the spread of the virus in the next two months. Traditionally, the country’s first-quarter economic growth rate is always the lowest of the year because of the Lunar New Year holiday, to be followed by a rebound in subsequent quarters. Beijing has already started to pump more money into the economy and more stimulus programmes are expected to follow.

However, as the virus has spread to more than 20 countries and many of them have effectively put China under quarantine by cancelling flights to the country and barred travellers from China, the country’s role in international trade and as a key player in the global supply chain have also been put to an acute test.

Hyundai, the world’s fifth-largest car maker, announced its decision on Tuesday to suspend production lines at its factories in South Korea as it relies on auto parts from China.

Many companies have started to relocate their operations from China, the world’s factory, to other countries because of the trade war between China and US. If the outbreak is not contained soon enough, it could accelerate the trend.

As a number of countries, including the United States and Australia, have started to evacuate their citizens stranded in Hubei, Britain and France have advised their citizens to leave the country altogether to reduce the risk of infections.

But what worries Chinese leaders most is that the epidemic and the initial cover-up by the local officials could prompt mainland citizens to direct their anger towards the party’s authoritarian centralised system. Since Xi came to power in late 2012, the country’s massive propaganda apparatus has ramped up rhetoric that the party’s dictatorship has made the country strong economically, militarily and technologically, making a grand showcase of China’s high-speed trains, cutting-edge AI applications, space ambitions, and new aircraft carriers as well as its Belt and Road initiative promising trillions of yuan for infrastructure developments from Asia to Africa.

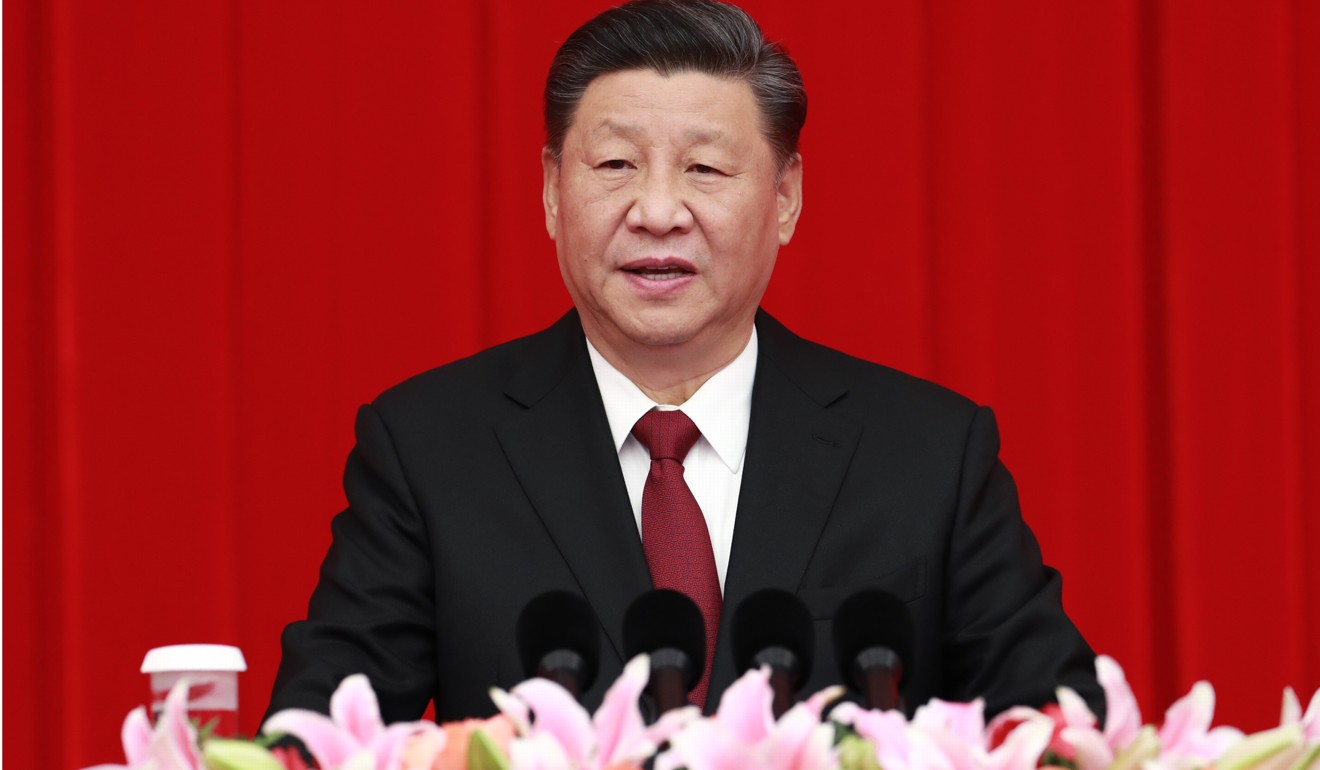

Chinese President Xi Jinping. Photo: Xinhua

But the epidemic has highlighted a woefully inadequate public health system and its emergency response mechanism. Until recently, doctors and nurses working in Wuhan and other cities in Hubei province where the most infections and deaths have occurred had experienced an acute shortage of medical-grade masks and protective clothes.

Thursday’s sad news about the death of Li Wenliang, a doctor in Wuhan who was cautioned by the police for sounding the alarm over the virus before he was sickened by it, has become a rallying cry on social media.

Having realised the bubbling public anger, the Chinese leaders have now promised to address “shortcomings and mistakes” in their response to the epidemic, promising to put the people’s lives and health as the top priority.

It is not hard to imagine that when the outbreak is contained, the Chinese leadership will again hail the wisdom of the authoritarian model as the key to mobilising national resources to defeat the “devil” virus. Local officials in Hubei would take the blame and be punished for their slow response to the outbreak and failure to implement measures by the central government in Beijing. Just like what happened in the aftermath of the Sars outbreak more than 17 years ago.

But this time round, restoring people’s trust and confidence in the party’s “system and capacity for governance” will be a lot harder. ■

No comments:

Post a Comment