By Caroline Rose

This week, the United Kingdom departs the European Union. For nearly three years the world has watched London exhaust itself over the political deadlock, delayed departure timelines, referendum propositions, and changes of political leadership. The world is well aware of what Brexit could mean for the U.K. and international markets, yet less has been said about what it will mean for the geopolitics of Europe.

The U.K., the EU’s second-largest economy, will withdraw from the region’s largest economic and political institution. Moments like these in history are bound to carry heavy, lasting geopolitical consequences with them, and this is especially the case in a post-Brexit Europe. As the Union Jack is lowered from flagpoles outside EU buildings this Friday, cracks in the EU’s institutional unity will be exposed, further throwing off the political balance between various regional blocs over matters like the eurozone, migration and regulatory policies, and reactivating the fault lines of one of Europe’s most historical competitions between Germany and France.

Economic Impact and the Regional Divide

When it comes to financial growing pains post-Brexit, the EU won’t go unscathed. While the political distraction of Brexit will fade, the EU will be forced to replace the U.K.’s contributions to its budget and navigate deeper, looming financial questions. Divergences will deepen between net contributors (mostly northern European states) and net recipients (southern and newer EU members to the east) over budget size, regional spending, integration, and of course, the eurozone. Brexit’s greatest economic impact will be on the EU’s inner workings, in the absence of one of the union’s largest budgetary contributors.

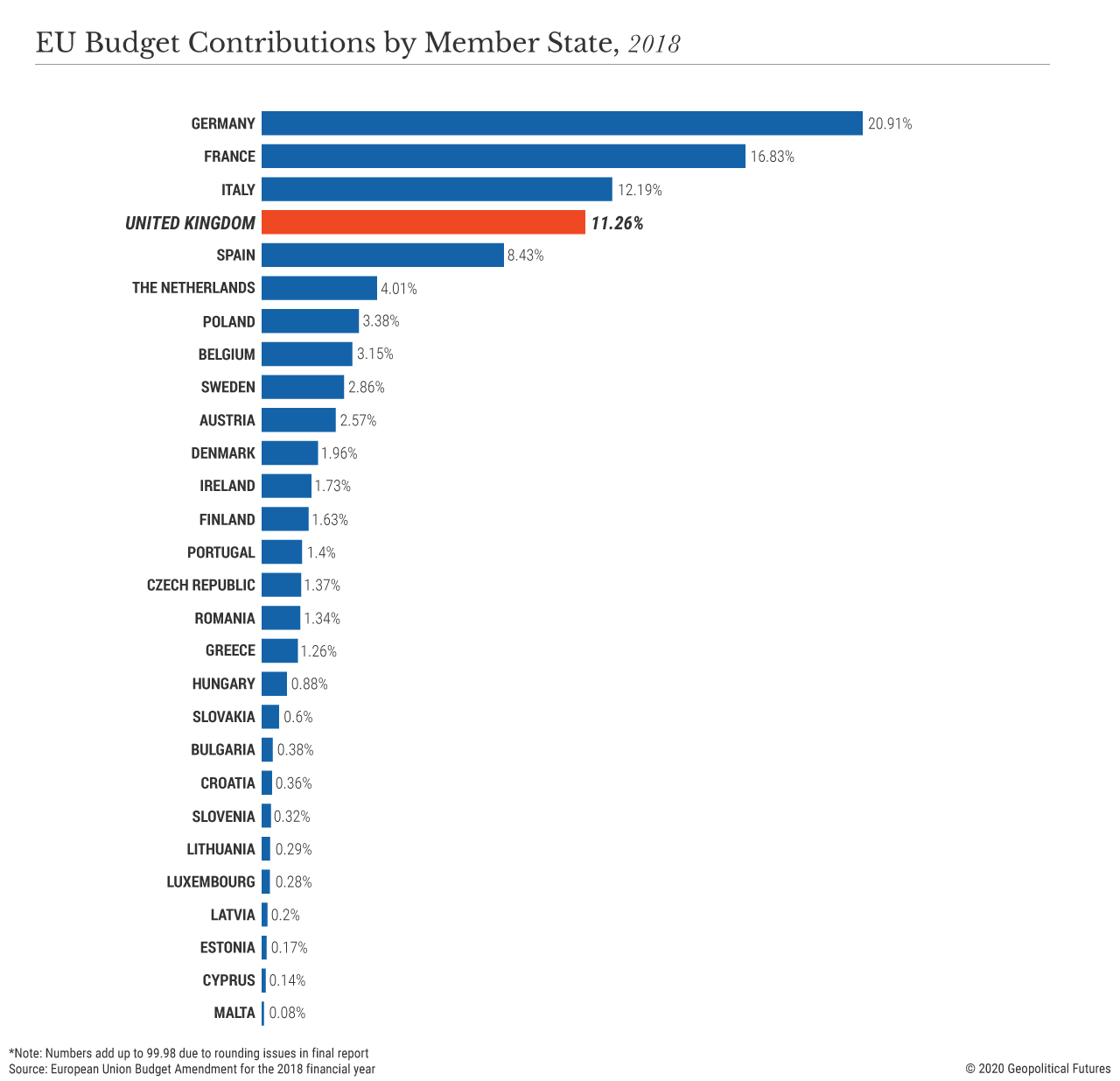

One of the largest sources of European tension will feature the EU budget, 11.26 percent of whose contributions in 2018 came from the U.K., the fourth-largest net contributor after France and Germany. Brexit is a large budgetary loss for the EU, an institution that has struggled with increasing financial contributions among newer, eastern European members. To make up for it, the EU has promised to reduce regional spending with the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and European Social Fund (ESF), and has pressured its wealthier, northern members to bump up budget contributions each year. (Germany will fill most of the gap, providing the largest share of upward of 33 billion euros by 2027.)

And these financial adjustments will not come without political tension. Brussels’ call to increase net budget contributions from wealthier northern states and keep the budget close to 1 percent of gross national income has indicated the growing influence of Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark, Austria and Sweden, the so-called “frugal five,” to maintain a more conservative budget that restricts regional spending. Most southern and eastern members are more dependent on the union’s regional spending and have begun to protest further cuts. This divergence over spending will inevitably spill over into the EU’s fundamental debate over prized farm subsidies, rebates and how to narrow the growing gap between net recipients and net contributors.

Northern, southern and eastern states also diverge on post-Brexit economic priorities — lingering differences that could aggravate European political disunity. While the EU’s northern members seek to co-opt the UK’s financial industry and preserve free trade, Brussels faces conflicting interests among its southern and eastern members that seek out agreements that can improve their own domestic financial situations, particularly the protection of agricultural cultivation and fisheries.

EU members also disagree over the scope of the union. Brexit will intensify the ongoing debate between EU members that wish to expand the EU with more accessions, and members that seek to conserve the size of the union and deepen integration among existing members, placing a greater emphasis on institutional reform. This divergence is the crux of the EU’s disunity, an imbalance that will become more volatile once the UK withdraws.

Politics, Defense and Foreign Policy

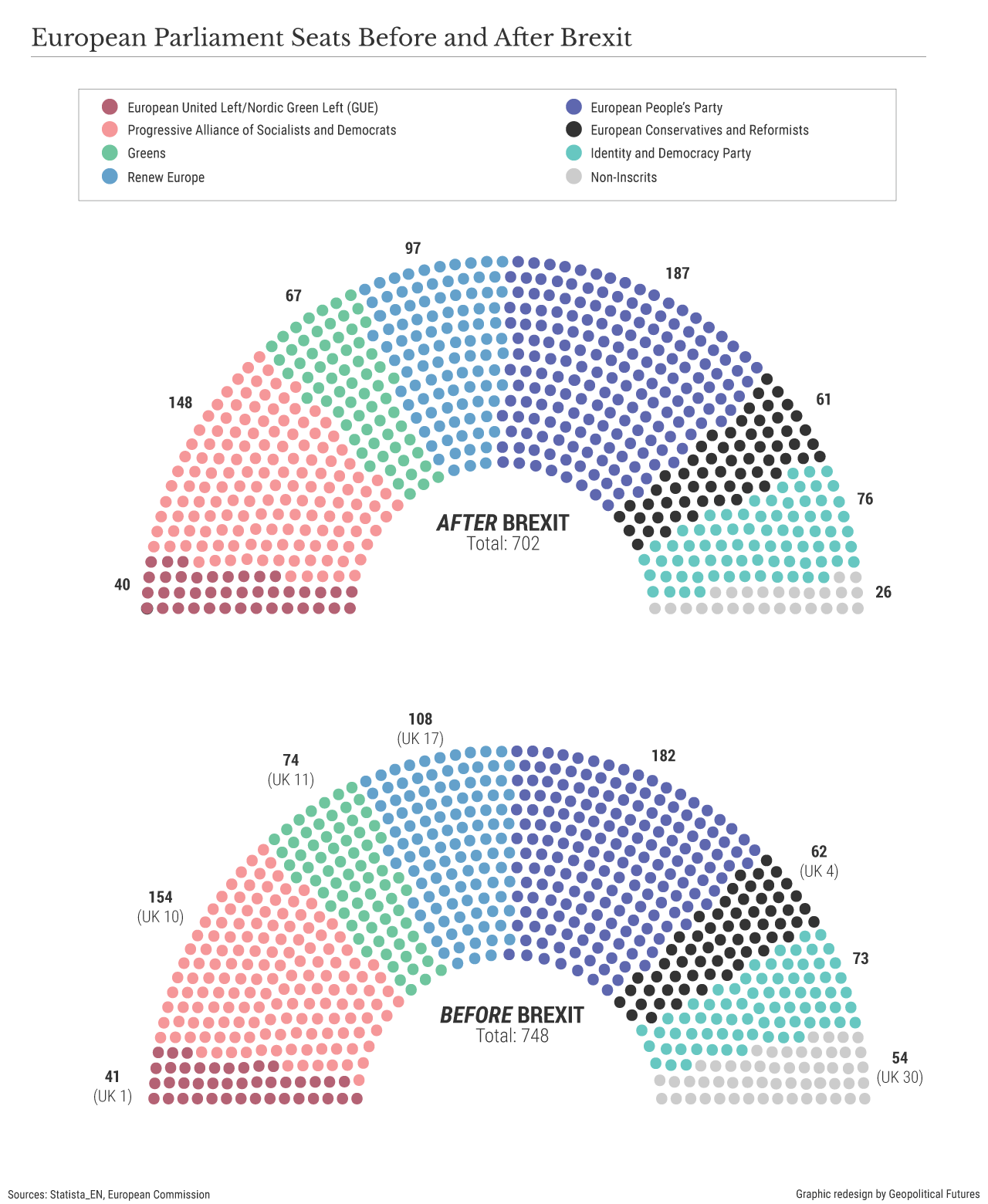

Before Brexit, the EU was already divided. There have been many concerns that Brexit will boost populist, euroskeptic movements that could further jeopardize the EU’s political and economic unity. France’s far-right leader, Marine Le Pen, said after the 2016 Brexit referendum that “The UK has begun a movement that will not be stopped.” However, these fears are exaggerated. Brexit has actually rallied pro-EU sentiment across the continent, with 61 percent of respondents in member states (excluding the U.K.) saying their country’s membership in the union was a good thing, according to a European Commission survey this year, up 8 percent from results shortly after the Brexit vote in 2016. The same survey reported that trust in the EU has increased in all member states, reaching its highest level since 2014. The institution is as popular as it was after the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, making any campaign for Swexit, Italexit, Nexit — really, any movement ending in “exit” — a risky venture. Britain’s costly Brexit saga has caused anti-EU parties in Italy, France, Germany, Austria and the Netherlands to dial back calls to depart the EU, refashioning their campaigns to focus on “reform” and “institutional change.”

The loss of the U.K. will send shockwaves through the bloc over foreign affairs and security. Brexit is a key influencer in the EU’s increasing experimentation with regional defense frameworks. Already, we have begun to see EU lawmakers attempt to recalibrate Europe’s defense structure, with calls to bolster its Common Security and Defense Policy and create a European Defense Fund. The loss of the U.K. is a loss of the EU’s largest defense budget contributor and second-largest armed force (right behind France), as well as the potential to weaken relations with the U.S. The U.K. contributed approximately 328 million euros to the CSDP in 2018, although it contributed modestly to EU CSDP missions and operations. And the U.K. also lent greater weight to the EU’s foreign policy. The loss of the U.K., with its array of full-spectrum defense capabilities and its status as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council (that wielded veto power on decisions involving sanctions, multilateral intervention, and security crises), is a blow to the EU’s foreign policy agenda.

Then there is issue of how the U.K. bridged transatlantic policies. The U.K.’s historical “special relationship” with the U.S. brought more clout to the EU, giving Brussels assurance that Washington was (somewhat) on the same page regarding defense, foreign policy and free trade. With the U.K. departing and a more hostile U.S. changing its relationship with the EU (threatening tariffs, troop withdrawal from Germany), Europe has been forced to seek new defensive alternatives. Certainly, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization is alive and well, but if the tensions over the 70th anniversary NATO summit tell us anything, it is that many EU members remain nervous about a lack of European military independence. EU members have begun to mold Europe as an autonomous actor in security and defense. The EU has begun to establish defense initiatives that run parallel to and compliment the NATO framework, endorsing measures that increase intra-EU defense cooperation such as the European Defense Fund, the Permanent Structured Cooperation, and the Coordinated Annual Review on Defense. While Europe has been strategizing for a more autonomous defense structure before the Brexit referendum took place, the U.K.’s withdrawal plays European anxieties over its lack of regional defense capabilities and will accelerate the EU’s efforts to increase cooperation.

An Age-Old Rivalry

Perhaps the greatest geopolitical consequence of Brexit is the reactivation of German-French power competition for EU leadership. The absence of the U.K. will allow Germany and France to rise to the occasion as mediating powers and policy leaders in the EU. However, this does not come without tension. Germany and France have historically been competitors in Europe, and as the German economy began to slow down and France sought a greater role in the EU, competition intensified. Ironically, the U.K. felt shut out of a French-German “romance” that dominated EU decision-making on certain issues, despite the U.K. not being a eurozone member (many Brexiteers cited this exclusivity as a reason to withdraw). Yet, the U.K.’s departure demonstrates how a perceived bilateral relationship was truly trilateral before Brexit — the U.K. held considerable weight in balancing out French-German tensions.

France is in a slightly more advantageous position than Germany post-Brexit. Germany, already on the precipice of a recession, faces a series of financial constraints, as it is expected to step up its financial contributions to replace the U.K. And because of these financial constraints, Germany must lead the charge in shrinking regional spending and slowing integration to where the budget does not exceed 1 percent of GNI. Germany sees this measure as a necessary policy, a way to smooth over wrinkles in the EU’s institutional framework before deepening integration, a policy that Berlin sees as a risk for further fragmentation. The U.K. was Germany’s ally in reigning in budgetary expansion and helped create a united front against the EU’s southern bloc. However, now Germany remains the sole enforcer, earning the reputation of “bad cop” among newer, eastern EU members that rely on these funds. France has already begun to seize on this opportunity and carve out a new leadership role, establishing itself as the “anti-expansionist, pro-integrationist” alternative to Germany.

It has harnessed southern and eastern members’ frustration with a hesitant, introspective Germany and has branded itself as Europe’s “change-maker” through a series of ambitious, expansionary policy proposals that Paris likens to an EU “renaissance.” France has led the call for quick-paced integration, deepening the relations among existing states as a way to combat disunity. France has also advocated a larger budget as an economic and social model for Europe, remedying southern members’ systemic financial issues and combating rising populism that could undermine the EU. And despite Germany’s calls to quicken accession, France has publicly opposed accession talks with Albania and Northern Macedonia, to Berlin’s chagrin.

This inevitable tug-of-war between Paris and Berlin has already begun to play out, with France contradicting German intentions by calling for military self-reliance, undercutting Germany’s bid for support of the Nord Stream II pipeline, flirting with the prospect of improving relations with Russia, and attempting to undermine Germany’s negotiating status at the Berlin Conference on Libya — just to name a few. However, we should not expect any resurrection of the Maginot Line anytime soon. In the face of nationalist movements and disunity in Europe, France and Germany understand that they have to show a united front. While both powers will take advantage of this new power vacuum left by Brexit, their EU leadership statuses demand limited cooperation. It is not a happy marriage, but divorce is not in the cards.

As the U.K. enters its transition period with the EU, the distraction that Brexit once occupied in Europe will begin to slowly subside, giving way to the structural issues that weighed down EU unity long before Brexit. In Brexit’s wake are a series of geopolitical shifts leading to the rebalancing of Europe. Lingering debates over the eurozone, the budget and spending, and expansion and integration will spark a crisis over securing European legitimacy and unity. And taking center stage in this crisis will be the German-French balance of power, experimenting with strengthened leadership roles to mold a new EU agenda and a remodeled Europe. While this Friday will mark a new chapter for the U.K. as a nation, it will mark a new era for continental Europe.

No comments:

Post a Comment