Hussein Ibish

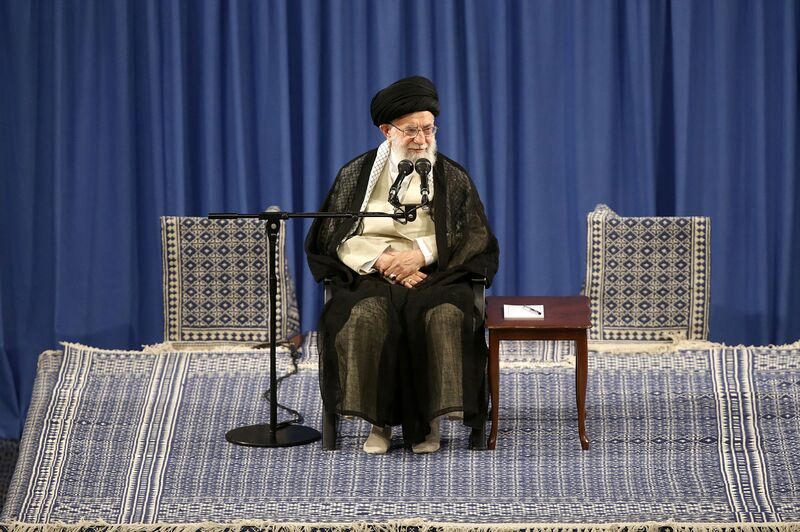

Now that the U.S. has taken out Qassem Soleimani, arguably the most important military figure in the 40-year history of the Islamic Republic, conventional wisdom holds that Tehran must respond with extreme prejudice. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has promised “severe retaliation,” and his regime is putting out videos of thousands of Iranian mourners demanding vengeance.

What might that mean? Many commentators—and not only in Iran or the U.S—are suggesting that a new war in the Middle East is inevitable. Some liken Soleimani’s killing to the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and on Twitter the hashtag #WWIII has been trending.

Not so fast. Iran may have many options for unleashing mayhem against American interests and allies in the Middle East, and plenty of allies and proxies through which to do so. But it also has a powerful reason to stop and reconsider. Beyond the expressions of outrage in Tehran—and alarm elsewhere—lies the cold reality that Iran cannot afford a war with a far more powerful opponent.

Any retaliation that leads to war will wreak enormous damage on the Islamic Republic. Even if costs more American blood and treasure than President Trump imagines, the toll on the Iranian nation will be many magnitudes greater. That is an outcome the regime in Tehran has consciously been trying to avoid.

The leaders of the Islamic Republic like to think of themselves as strategic thinkers, with a keen understanding of their opponents and a knack for anticipating their next moves. But they clearly misjudged Donald Trump. Convinced the American president would do anything to avoid a war, they have for months been provoking the U.S. with progressively more intense provocations.

Their goal all along has been to force the U.S. to ease the economic sanctions Trump imposed after he withdrew from the nuclear deal in May 2018. The regime Tehran initially tried to wait out the sanctions, but discovered they were more painful than expected.

A year later, by May 2019, they began a campaign of intimidation by attacking commercial shipping in international waters, but were careful not to actually sink ships or kill anybody.

Tehran was counting on provoking disproportionate U.S. response, short of actual war but enough to create a crisis and prompt international diplomatic intervention to get both sides to back down. In this scenario, Iran would be “persuaded” to stop its attacks, and the U.S. to ease the sanctions.

When the first round of provocations didn’t get a response, the Iranians shot down an American military drone. Trump called off a retaliatory strike at the last minute, but he announced a “red line”: the death of any American at Iranian hands would mandate a military response.

So, Iran raised the stakes by unleashing a major attack on Saudi oil installations. The U.S. moved troops to Saudi Arabia, but again did not respond kinetically.

At that point, Iran’s proxy militias in Iraq, especially Kata’ib Hezbollah, launched a series of rocket attacks against U.S.-related facilities in Iraq. This campaign culminated last week with an attack that killed an American contractor, several Iraqi police and soldiers, and wounded four American troops.

Throughout this calibrated testing of the limits of American patience, the regime in Tehran was certain that Trump didn’t want a war. When his red line was crossed, however, they discovered he wasn’t quite as conflict-adverse as they assumed.

First, U.S. strikes on Kata’ib Hezbollah bases killed at least 24 militia cadres. Then, after the group’s members violently besieged and damaged the U.S. Embassy compound in Baghdad, the Trump administration claims it picked up credible intelligence that Soleimani was plotting further attacks on American interests and personnel in Iraq.

Evidence for this has not been provided, but such behavior is consistent with Iran’s escalating provocations. Soleimani’s presence in Iraq, where he was traveling with Kata’ib Hezbollah leader Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis will have hardened suspicions. Both were killed in the U.S. drone attack, and several more pro-Iranian Iraqi militia leaders may have been killed in a subsequent strike last night.

What now? The Iranians can no longer be under any illusions about Trump’s appetite to answer provocations with disproportionate force. The killing of Soleimani was the most severe attack on the Iranian political apparatus the U.S. could have inflicted outside of Iran. Khamenei must know now “severe retaliation” by Iran could be met with an even more devastating American response. He might still calculate that Trump doesn’t want all-out war, but that gamble is much riskier than it was last week, last month, or last year.

The smarter option for Iran would be to take Secretary of State Mike Pompeo seriously when he says the U.S. is now looking for de-escalation, and restrict their retaliations to thundering threats. The regime might, instead, harvest some international sympathy, however undeserving, for Soleimani’s killing. And the outpouring of national grief could distract Iranians from the recent slaughter of hundreds of their countrymen, ordered by Khamenei and executed by Soleimani and other commanders.

If the regime is driven by ideology and emotions, it will live up to Khamenei’s word and retaliate harshly—at great cost to Iran and the whole region. But if it is rational, as it tends to be in a crisis, it will take the opportunity for a long pause in the pattern of escalation with the U.S., and find a new strategy that does not drag everyone towards a devastating conflict.

No comments:

Post a Comment