Matt Clark

If ever we’re asked to do anything in the future, whatever it is . . . you can requisition whatever you need. If you need tents, I’ll get you tents. If you need canteens, I’ll get you canteens. If you need more rifles, I can get you more rifles. Or shovels, vehicles. You can requisition that. You can’t requisition, when the moment comes, trust, discipline, and fitness.

If ever we’re asked to do anything in the future, whatever it is . . . you can requisition whatever you need. If you need tents, I’ll get you tents. If you need canteens, I’ll get you canteens. If you need more rifles, I can get you more rifles. Or shovels, vehicles. You can requisition that. You can’t requisition, when the moment comes, trust, discipline, and fitness.

— Gen. Martin Dempsey

The US Army is a force with extraordinary expeditionary capabilities. We send our soldiers around the world with remarkable regularity to fulfill a range of vital missions. But when we deploy units globally—whether to the ongoing mission in Afghanistan, to work with partners to defeat ISIS, or to reassure allies and conduct combined exercises in Europe or the Pacific—a big problem arises, one that we unfortunately don’t talk about. The Army routinely deploys its soldiers when they are at their lowest level of physical fitness.

This needs to be fixed. It is not only unacceptable but also entirely preventable. The Army’s replacement of the Army Physical Fitness Test with the more wholistic Army Combat Fitness Test is designed to “transform the Army’s fitness culture” and improve readiness for ground combat. This goal is laudable and the new test does signal a shift in the Army’s focus to a more functional form of fitness. However, this effort will fail to maximize combat readiness without addressing a deeper cultural issue that is largely ignored. It is not enough to train on the right tasks; that training must be maintained through consistency.

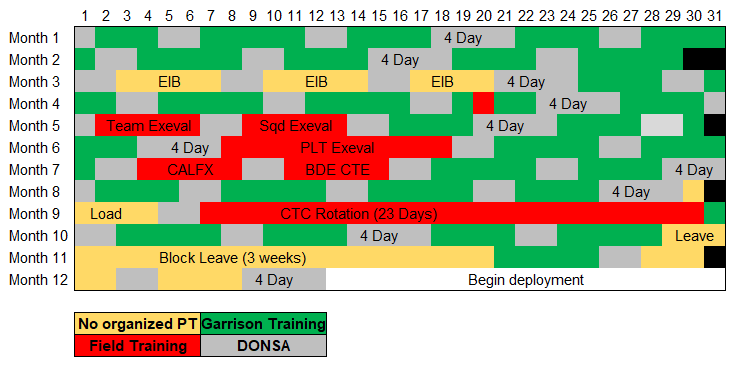

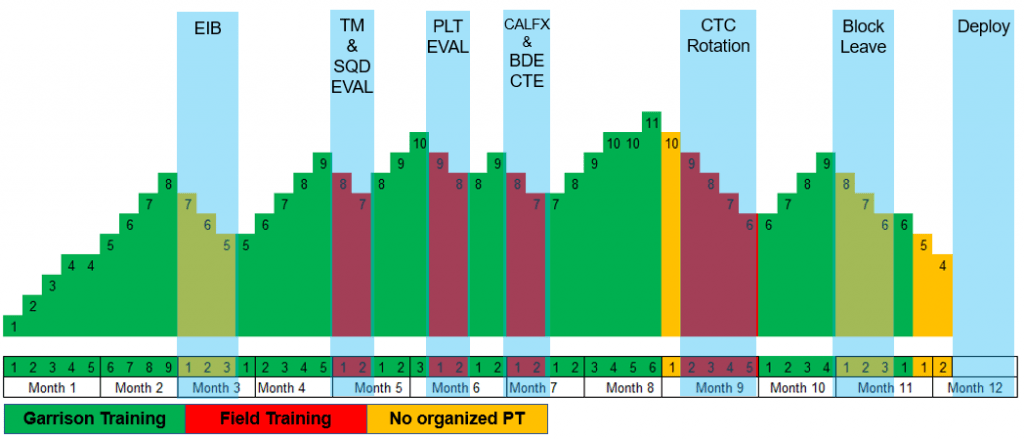

Most soldiers spend three to four months of the year conducting field training and other events that interfere with organized physical training, as shown in figure 1, and most units do not conduct deliberate, consistent physical training in the field. This inconsistent training leads to a “seesaw” effect where soldiers are continually losing and rebuilding fitness. The overall impact on readiness is compounded by the fact that units spend increasingly more time in the field as they progress through their collective training cycle. Figure 2 overlays a typical training schedule with a simplified model that assumes one unit of fitness gain for each consistent week of training, and one unit of loss for each week of poor training or no training. The result: a unit’s lowest dip in physical readiness coincides with its peak in tactical readiness. Maximum combat readiness—a combination of both—is never achieved.

Figure 1: Generic twelve-month battalion training plan.

Figure 2: Fitness gains and losses in standard unit training cycle.

These “field losses” in fitness are so normalized in Army culture, most leaders never give them a second thought. Further, the model in figure 2 is overly generous in depicting fitness gains for the average soldier. Even in “garrison” training, an array of things interfere with consistent fitness, including early departures for ranges, preparation for line haul, individual appointments, and various unit taskings.

This recurring loss of fitness is unnecessary and occurs when leaders at all levels view physical training and tactical training as incompatible. This tradeoff paradigm falsely assumes that fitness must be sacrificed to achieve tactical competence, and vice versa. It is supported by a series of widely accepted myths related to physical training in the field environment. To maximize soldier and unit combat readiness, leaders at all levels must adopt a new paradigm that integrates tactical and physical training to improve overall combat readiness.

The Eight Myths that Fuel the Tradeoff Paradigm

This failure to follow the basic fitness principle of consistency is not due to a lack of knowledge. The principles of physical training, to include the required frequency, as well as the full breadth of physical fitness components, are well documented in the Army’s most recent physical fitness manual. The manual even provides recommendations on the conduct of physical training in the field.

With this knowledge readily available, why do leaders who routinely emphasize the importance of physical fitness compromise the principal of consistency so frequently? Conversations with dozens of soldiers, noncommissioned officers, cadets, and officers suggest eight common myths that reinforce the tradeoff paradigm.

1. The “Zero Sum Game” Myth. One common reason provided by leaders for not conducting physical training in the field is that there is just not enough time. Any time devoted to physical training is believed to detract from tactical training. This is a short-sighted perspective. It takes more time to regain lost fitness than it does to maintain existing fitness, not to mention training time lost to injuries caused by lack of soldier fitness. This is no different than any other leader challenge in which there are inherently more tasks to complete than time in which to complete them. Leaders set priorities and schedule these priorities into available training time.

2. The “No Time Outs” Myth. This is the belief that in order to conduct the tough, realistic training necessary to get ready for combat, units must be immersed in a wartime scenario 24/7. Short “admin” halts to perform physical fitness will not significantly disrupt combat training. These halts are already incorporated into most training events to verify accountability of personnel and equipment and conduct after-action reviews—because losing equipment in a training environment is unacceptable and after-action reviews add immense training value. Leaders must be just as diligent in safeguarding fitness and recognize the value it adds to training and long-term readiness.

3. The “Mission Impossible” Myth. Too many people feel that it is impossible to conduct good physical training in the field due to a lack of resources. Therefore, it is believed that any attempt at field physical training is a waste of time, a check-the-block activity. This belief is fueled by two things: leaders with a lack of knowledge on how to plan and manage physical training in the field and soldiers with cynical attitudes based on poorly run “field PT” sessions in the past. The truth is that effective physical training can still be conducted, even with limited resources. It simply requires deliberate planning and some creativity.

4. The “All or Nothing” Myth. This is the belief that if physical training cannot be conducted to the same quality in the field that it can in garrison, then soldiers might as well not do any physical training at all. The truth is that more consistency leads to better performance outcomes. Some studies have shown that reduced volume of training can be offset with increased intensity. But in any case, something is always better than nothing. Seek gains, maintain fitness, or at a minimum, fight the losses.

5. The “Everything I Do is PT” Myth. Some soldiers have said that physical training is unnecessary in the field because “we are doing PT in the field, all day.” Some field activities are indeed physically strenuous—ruck marching or conducting react-to-contact, for example. And overtraining is a legitimate concern, especially in hot climates. However, the truth is that most of the fitness spectrum—to include muscular strength, anaerobic endurance, power, speed and other aspects of mobility—are often neglected in the field, as shown in figure 3. Marching with gear on primarily works only a narrow band of fitness—muscular endurance of the back, shoulders, and leg muscles and sometimes cardiovascular endurance. And brief spurts of intense activity, such as sprinting for cover, do not naturally occur at the consistency required to achieve fitness gains related to speed or anaerobic endurance. Proper planning that factors in the tactical training schedule can prevent overtraining while exercising areas that are typically neglected.

Figure 3: Components of fitness exercised naturally in typical field training exercise.

6. The “Surge on Fitness” Myth. This is the mistaken belief that by working out harder after coming out of the field and specifically in the weeks immediately before a physical fitness test, soldiers can build good fitness. This is similar to students who delude themselves into thinking they are learning when they cram the night before a test. The surge approach does not sustain the high levels of fitness expected for units that must be ready to deploy on short notice. Further, frequently taking time off and then pushing hard is more likely to cause overtraining injuries. Most trainers recommend following the 10 percent rule to incrementally increase intensity and avoid injuries, but gaps in training require falling back to a lower level.

7. The “PT is an Individual Responsibility” Myth. This myth is actually reinforced in the Army’s physical fitness manual, which states that “all soldiers must understand that it is their personal responsibility to achieve and sustain a high level of physical readiness and resilience.” Given the demands leaders place on soldiers in the field and various other events, this is unrealistic and unfair to the soldiers. While individuals are responsible to do their share, leaders make decisions that set the conditions for success or failure. If fitness is a priority, leaders must allocate and protect time for their soldiers to conduct physical training consistently.

8. The “Fit Enough” Myth. This is the belief that a soldier who can meet the minimum requirements on a fitness test is “fit enough.” Fit enough for what? Accepting mediocrity is not a strategy adopted by any winning team. Minimum standards exist to certify a baseline, entry-level capability, not as a guarantee of victory. The very nature of our profession demands excellence. We prepare to fight enemies that are committed, smart, and adaptive. If we want to win, we must do everything possible to maximize our performance. We are never “good enough.” Winners pursue excellence.

Further, it is important to keep in mind that improving physical capacity is not the only reason to conduct physical training. Among other things, physical training builds self-confidence, self-discipline, and resilience. As President John F. Kennedy once famously remarked, “physical fitness is the basis for all other forms of excellence.”

“Train as you Fight”: The One Time it May be Good to Skip Field PT

While none of these myths are valid reasons to skip physical training in the field, there is one good reason leaders must keep in mind—inadequate rest and recovery due to simulating combat conditions. To truly maximize combat readiness, this justification must be used deliberately and much less frequently than it currently is.

A well-known principle of Army training is to “train as you fight.” Assessing the requirements of future war, Gen. Mark Milley remarked that soldiers must learn to “embrace the suck,” to be miserable and constantly on the move. For soldiers, adhering to the “train as you fight” principle requires simulating the stress and misery of combat. A common way that leaders add this stress is to train at a high operational tempo, reducing the amount of time for food or sleep that soldiers get. This does effectively add stress, and it may even build mental toughness and unit cohesion through the shared suffering. However, the idea that “sleep deprivation makes us better” warrants scrutiny. A more accurate statement might be that such misery makes soldiers mentally tough and physically weak.

Multiple research studies suggest that good sleep enhances muscular recovery in a variety of ways, while lack of adequate sleep prevents recovery. Sleep significantly impacts athletic performance. While the exact amount of sleep necessary to recover physically varies by individual, a general rule of thumb is that seven to nine hours of rest supports optimal performance. Anything less than this leads to suboptimal recovery and performance. Lack of adequate recovery, rest, or nutrient intake can lead to symptoms of overtraining syndrome, to include stress fractures, heat injury, and rhabdomyolysis—the breakdown of skeletal muscle. Without adequate sleep, physical training may further degrade rather than build physical readiness.

This leads to two considerations for leaders. First, leaders should consider how often soldiers need a “crucible” experience that degrades physical readiness through loss of sleep and nutrition in order to prepare for combat. There are other ways to make training tough and realistic, to include time constraints and grueling physical events. Second, if soldiers do experience significant sleep loss over consecutive nights, leaders may determine that physical training focused on strength or endurance may do more harm than good. Mobility exercises can still be performed, but exercises that further break down muscles that are unable to rebuild themselves will not lead to fitness gains.

Achieving Sustainable Combat Readiness

The more you sweat in peace, the less you bleed in war.

Leaders can and should seek to maximize both tactical and physical readiness simultaneously. This requires dropping the tradeoff paradigm and pursuing an integrative solution to building and maintaining combat readiness.

Sustaining maximum combat readiness within a “band of excellence” is, after all, the purpose of the Army’s new Sustainable Readiness Model, avoiding the sharp fluctuations experienced under the previous Army Force Generation framework.

Figure 4: The “band of excellence” for physical training.

Institutional-level changes related to how the Army mans, equips, and trains units have put the Army on a glide path toward achieving this goal for tactical readiness. However, to sustain a “band of excellence” for physical readiness requires more consistent physical training. Physical training must be integrated into field training exercises, and leaders must be deliberate and judicious in choosing when to incorporate sleep deprivation as a means of simulating combat stress.

The arrival of the Army Combat Fitness Test is a positive change, returning soldiers to a focus on the full spectrum of combat fitness. In the Cold War era many civilian and military leaders believed ground warfare to be obsolete, which factored in the decision to replace the previous combat-focused fitness test with the Army Physical Fitness Test in 1980 as a measure of general “physical fitness and health.” The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq proved this to be false, and Gen. H. R. McMaster has since emphasized that believing the United States can opt out of land conflict is an enduring fallacy. Looking forward, the Army’s developing Multi-Domain Operations concept identifies the need for physically fit soldiers to be prepared to fight in highly contested domains, including readiness to fight in uniquely challenging environments like dense urban terrain. Both tactical and physical readiness will remain key components of combat readiness.

The tradeoff paradigm and the eight myths that support it are deeply ingrained in the Army culture, presenting a significant challenge to reaching this goal. But the second piece in this two-part series will show that it is possible. Change will require leaders at all levels to actively resist these myths, seek better understanding of how to plan and execute physical training in austere and time-constrained environments, and fight through the friction to integrate tactical and physical training. The result will be a more combat-ready US Army.

Maj. Matt Clark is an Army Special Forces officer and instructor at the United States Military Academy’s Simon Center for the Professional Military Ethic. He holds a master of arts in social-organizational psychology from Teachers College, Columbia University and a bachelor of arts in psychology from Cedarville University.

No comments:

Post a Comment