With the year 2019 coming to a close, the world is poised to enter a brand new decade of promise, opportunity, and unpredictability. None of us have a crystal ball; we can only hope that the next stretch of time is peaceful and prosperous, devoid of the kind of superpower conflagrations that defined the Cold War period.

Progress over the next decade will depend in large measure on our ability to avoid the kinds of self-inflicted wounds that can make our lives hell. For the men and women who have the privilege and weighty responsibility of running U.S. foreign policy in the future, avoiding mistakes means looking back in time and recognizing when judgment was poor and when policy errors were made. There is no better time to perform this exercise than at the end of a calendar year.

So as we say goodbye to the 2010’s, here are three of the worst foreign policy mistakes the United States made over the last decade.

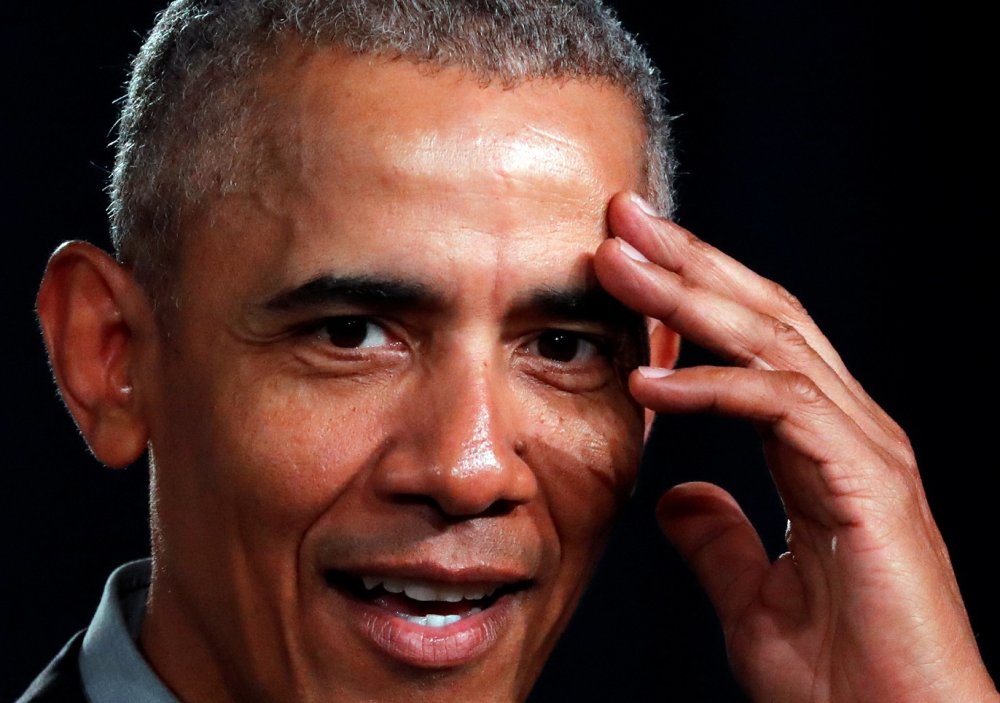

1. Regime-change in Libya: The U.S. and NATO-led military operation against Libyan dictator Muammar al-Qaddafi was packaged by the Obama administration as an urgent mission to save innocent lives who would have otherwise been slaughtered by Libyan forces. With the exception of Afghanistan, a war inherited from the previous White House, the air campaign in Libya was President Obama’s first overseas military engagement.

Not to put too fine a point on it, the intervention ended up being a colossal disaster. As President Obama admitted himself to the Atlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg in a 2016 interview, “it didn’t work.” Obama would later label the Libya intervention and the failure to prepare for the post-conflict phase the worst mistake of his presidency.

United States Navy SEALs established.

Ellis Island opens to begin processing immigrants into the United States.

It’s difficult to disagree with Obama’s categorization. Nearly nine years after the operation, Libya has descended into a real-life Mad Max. The North African oil producer can best be described as anarchic, with foreign mercenaries pouring into the country at the urging of the combatants, drones from multiple countries firing missiles on various targets (many of them civilian), and Islamic extremists taking advantage of the chaos by carving out their own fiefdoms. Libya is no longer a sovereign nation, but rather a wide-open arena for regional powerhouses like Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, and Russia to fight one another through their respective Libyan proxies. The 2011 intervention also proved to be a major push factor for tens of thousands of people who would rather embark on a risky journey to Europe across the Mediterranean than stay in a war-pocketed hell hole. The ensuing refugee crisis in Europe would go on to contribute to the rise of far-right populist politicians across the continent, shaking the European Union to its foundations.

2. Withdrawing from the Iran nuclear deal: The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action wasn’t the perfect accord, but it served a valuable purpose: rolling back Iran’s uranium enrichment activities to the root and providing the international community with its first, in-depth look at the nuts-and-bolts of Tehran’s nuclear program. The Arak nuclear reactor was filled with cement and rendered inoperable; thousands of centrifuges were ripped out and placed in storage under International Atomic Energy Agency seal; Iranian officials were forced to divulge information about their past nuclear work; and IAEA inspectors were granted continuous access to a range of facilities on Iranian soil, monitoring every step of the enrichment process.

And then it all came tumbling down.

For reasons still not entirely clear—President Donald Trump’s aversion to anything Obama did; a belief that he could get a bigger and better deal from Tehran at a lower cost; the tenacity of his hawkish national security advisers; or perhaps all of the above—the Trump administration threw it all away by withdrawing from the agreement and reimposing the very sanctions regime that was lifted years before. Far from dragging Iranian leaders back to the negotiating table and putting the regime in a more desperate position, Trump’s decision to squeeze the Iranian economy to the point of bankruptcy was met with a fierce Iranian response. Civilian cargo ships have been sabotaged. Cruise missiles have struck Saudi Arabia’s oil facilities. A U.S. reconnaissance drone was shot down. Crew traveling through the Persian Gulf were detained. And Iran’s nuclear engineers started enriching uranium in more places, in higher grades, and with more advanced machines.

3. Giving Saudi Arabia a pass: The decade has been very kind to the Saudi Royal Family, both in terms of the amount of political capital they have acquired in Washington and in the quantity and quality of the weapons systems they have purchased. The Congressional Research Service pegs the U.S.-Saudi arms trade from 2010-2019 at nearly $140 billion, making Riyadh the biggest buyer of American defense equipment in the region by far. Some of those weapons, from the combat jets to the precision-guided munitions, have been used over the last four years to pummel Yemen—already the poorest country in the Arab world—into the stone age. Riyadh’s air campaign against the Houthis, designed to last a few months at the most, long ago turned into the world’s ugliest humanitarian catastrophe. More than half of the country’s health facilities are shut down, more than two-thirds of Yemenis need humanitarian assistance, 7.4 million are at risk of famine, and 4.3 million have evacuated their homes.

The Saudi intervention in Yemen—made worse by Washington’s military and political support of Riyadh—convinced Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman that nothing the kingdom did would have negative repercussions. In Mohammed’s mind, the United States needs Saudi Arabia more than the other way around. This sense of impunity, along with MBS’s extreme paranoia, helps explain why he would be so reckless since he ascended to the position of the crown prince. From boycotting Qatar and kidnapping the Lebanese prime minister to dispatching operatives to murder a Washington Post columnist, the 30-something crown prince has acted like a hell-raising child without adult supervision. By giving Saudi Arabia the benefit of the doubt and treating the country as the golden boy in the Middle East, two successive U.S. administrations have managed to create a monster.

Welcome to 2020!

Will Washington be able to dodge similar mistakes in the 2020’s? This is certainly the hope. But if U.S. officials are too afraid to come to terms with their own-goals over the last decade, they are flirting dangerously with failure.

No comments:

Post a Comment