From Albert Einstein letter, Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, December 1946

From Albert Einstein letter, Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, December 1946

We live in an increasingly dangerous nuclear world, a time at least as perilous as the worst years of the Cold War. The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists’ Doomsday Clock offers a clear representation of existential risk. In 1953, when first the United States and then the Soviet Union began testing thermonuclear weapons, the Bulletin Science and Security Board set the clock at two minutes to midnight. Over the intervening six decades the nuclear threat fell and rose, and fell again, but few would dispute that in recent years the alarm has been sounding for those who would hear it. Today, the Science and Security Board set the Doomsday Clock at 100 seconds to midnight—closer than it has ever been to catastrophe—warning that “any belief that the threat of nuclear war has been vanquished is a mirage.”

There is an urgent need to bring together expert voices and informed, mobilized public pressure that once proved so important as a source of demands and options to reduce nuclear threats. The physics community can be an influential advocate for this goal. With support from the American Physical Society (APS), physicists from a collection of universities have recently begun a project to recruit and organize physicists to take on this challenge. The Physicists Coalition for Nuclear Threat Reduction plans, through grassroots efforts, to establish a network of citizen-scientists committed to nuclear threat reduction. The participation of women, minority, and next-generation physicists—all currently underrepresented in nuclear policy debates, but whose voices must be part of such a new effort—will be a key ingredient.

The current crisis. Today, as before, it is mostly the nuclear-weapon states driving the geopolitics and technologies that underpin this increasing threat. The danger of the current moment is captured clearly in recent remarks by United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres: “Relations between nuclear-armed states are mired in mistrust. Dangerous rhetoric about the utility of nuclear weapons is on the rise. A qualitative nuclear arms race is underway. The painstakingly constructed arms control regime is fraying. Divisions over the pace and scale of disarmament are growing. I worry that we are slipping back into bad habits that will once again hold the entire world hostage to the threat of nuclear annihilation.”

The massive nuclear weapon system modernization being undertaken by the United States and Russia and, to a lesser extent, by China, France, and the United Kingdom constitutes a renewed century-scale commitment to nuclear weapons and includes the development of new offensive, defensive, and detection systems. These programs are accompanied by destabilizing technological developments, such as the development of antisatellite weapons that threaten early-warning and communication satellites, and the possibility of cyberattack against nuclear command and control systems. Cast aside is the obligation of these states since 1970 under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty “to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament.”

Once abandoned, arms control will be difficult to re-establish. The unraveling of the system of Cold War superpower treaties and agreements that kept a lid on US and Russian arms may be cause for the greatest concern. US refusal to ratify the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty in 1999 and its withdrawal in 2002 from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABM) and in 2019 from the Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty set the stage for the current predicament. The destabilizing effect of abandoning the ABM Treaty is already evident in Russia’s development of new offensive weapons, subsequent counter-moves by the United States, and China’s buildup of its strategic nuclear forces. New intermediate range weapons, which can be armed with both conventional and nuclear warheads, are being pursued both by Russia and the United States. Their last remaining bilateral nuclear arms control treaty—New START—is scheduled to expire on February 5, 2021. If the Treaty is allowed to expire without renewal, for which there are indicators, then for the first time in 50 years Russian and US arsenals will be unconstrained by any treaty. Mutual on-site inspections and data exchanges, which have served as major confidence-building measures, would end along with the treaty, fueling worst-case assessments of the capabilities of the other side.

The Cold War was punctuated by nuclear crises and close calls—at least one each decade, it seems. This was with only two players: the superpowers. While Russia and the United States still possess the vast majority of nuclear weapons, the increased influence of the other seven nuclear weapon states, with a complex web of relationships and dependence, provides more scenarios that can lead to nuclear conflict. Even a regional conflict might lead to global catastrophe through climate cooling effects from carbon soot arising from the urban firestorms ignited by nuclear weapons.

The above incomplete litany of increasing dangers is well-known and well-articulated within the arms control community. But it is not well-appreciated within the public or the larger scientific community. This disconnect is most unfortunate. The governments of nuclear weapon states are not solving the problem; rather, they are enhancing the threats. Thus, attainment of a safer world demands additional external pressure on these governments.

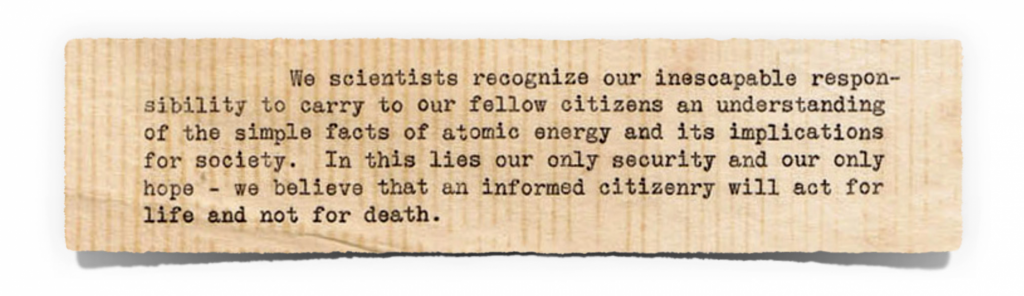

Unto the breach. In the early years of the nuclear age, physicists warned of the danger of nuclear weapons. As early as 1946, the comprehensive, yet stunningly succinct statement of six facts by the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, chaired by Albert Einstein, captured presciently the looming nuclear threat:

Atomic bombs can now be made cheaply and in large number. They will become more destructive.

There is no military defense against atomic bombs, and none is to be expected.

Other nations can rediscover our secret processes by themselves.

Preparedness against atomic war is futile and, if attempted, will ruin the structure of our social order.

If war breaks out, atomic bombs will be used, and they will surely destroy our civilization.

There is no solution to this problem except international control of atomic energy and the elimination of war.

Throughout the decades to follow, many physicists worked to advance arms control, a struggle documented in Matthew Evangelista’s path-breaking Unarmed Forces: The Transnational Movement to End the Cold War. Organized action by physicists has been effective. For example, in the 1970s physicists played a key role in making the case for limitations on ballistic missile defenses because they could be defeated with countermeasures and would stimulate offensive buildups and, in the 1980s, physicists came to the defense of the ABM Treaty, contributing to the curtailment of the Strategic Defense Initiative.

As David Meyer observed in his study A Winter of Discontent: The Nuclear Freeze and American Politics, “scientists have been among the most active and credible spokespeople” for movements in the United States against nuclear threats. Many leading physicists, including figures such as Hans Bethe, Philip Morrison, and Bernard Feld (an editor-in-chief of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists) joined with the public in supporting the Nuclear Freeze movement of the 1980s, which brought 1 million supporters to New York’s Central Park and reportedly helped propel President Reagan to open negotiations for the massive nuclear arms reductions that followed.

Today, however, the threat posed by nuclear weapons is off the radar of the physics community in the United States and the other nuclear weapon states. This reflects to some extent the overall post-Cold War reduction in concern among the general public about potentially civilization-shattering nuclear wars. Some may be lulled into false comfort by the 70-year absence of a nuclear detonation during conflict; others may feel powerless in the face of a nuclear weapons enterprise that survived the end of the Cold War and seems resistant to all efforts to end it, and many have turned their attention to more visible dangers such as those posed by climate change, and to economic and social injustice issues. However, if re-engaged and activated, the physics community can again be an influential voice in informing the public, Congress, and other key stakeholders of the necessity of restraint and the path toward nuclear risk reduction.

A new physicists coalition. We have joined with other concerned physicists from a handful of universities across the country (the University of California, Berkeley, the University of Illinois, the University of Maryland, MIT, Princeton University, and Stanford University) to begin to build a Physicists Coalition for Nuclear Threat Reduction. The key goal of this project over the next two years is to establish a network of citizen-scientists committed to understanding, explaining and advocating for nuclear threat reduction. We believe that there is a latent interest in nuclear arms issues among physicists that can be sparked by the new project. And here we define “physicists” broadly, to include all physical scientists, including those in engineering science.

This multi-institutional effort is supported by the American Physical Society (APS) through its Innovation Fund and is partnered with its Office of Government Affairs. The APS is a membership organization representing more than 55,000 physicists in the United States and throughout the world and its mission includes advancing the use of physics for the benefit of humanity. The project is managed through the Program on Science and Global Security at Princeton University.

We will use a grassroots approach to inform US physicists on nuclear threats and possible threat-reduction measures, recruit interested scientists to the coalition, and connect those scientists to the public debate and policy process. As a first step, the project will enlist experts in nuclear arms issues to carry the messages directly to physicists in universities, at professional meetings and conferences, in national laboratories, and in industry. For those physicists who are interested in becoming active, we will facilitate partnerships with community-based citizen groups already working on this agenda, merging technical knowledge with organizational capabilities. Together they can educate members of Congress and the media on nuclear policy issues.

There are numerous concrete policy measures the United States can implement to reduce the nuclear threat and which are possible advocacy positions for the coalition. These include extending the New START Treaty, adopting a no-first-use policy, abandoning the launch-on-warning option, abandoning the destabilizing intercontinental ballistic missile leg of the US nuclear triad, and re-establishing limits on missile defense systems,.

We are at a potentially ominous turning point in the nuclear world order. It calls for collective and organized engagement by the US physics community. The coalition can encourage a more informed and active national debate on nuclear weapon policies and, we hope, serve as an example for similar actions in other professional communities and in other nations.

No comments:

Post a Comment