By: Adnan Aamir

Introduction

Leaders in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan were stunned in late November when a senior U.S. government official issued a strong verbal attack on the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). On November 21 in Washington, D.C., U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for the Bureau of South and Central Asia Affairs Alice Wells spoke at length about the CPEC at a public event, criticizing multiple elements of the $62 billion flagship component of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Ambassador Wells cast doubt upon claims that CPEC will generate sustainable economic development in Pakistan and criticized the project’s cost escalations and non-transparent processes of awarding CPEC contracts to Chinese firms. She appealed to Pakistan’s citizens to ask tough questions of the PRC regarding the CPEC and China’s related projects in Pakistan (U.S. State Department, November 21, 2019).

In the past, the U.S. government had raised concerns over CPEC and China’s “debt-trap diplomacy,” but it had never presented such a direct and detailed set of criticisms. Ambassador Wells crossed that line—bringing the notoriously stalled out CPEC back under international scrutiny just after Chinese and Pakistani leaders had brokered a cautiously optimistic set of funding deals to jumpstart progress a month before (Ministry of Foreign Affairs (PRC), October 9, 2019). Chinese representatives were quick to respond to Ambassador Wells’s criticisms. The next day, PRC Ambassador to Islamabad Yao Jing(姚敬) said that he had been “shocked and surprised to see the remarks of Alice,” and that Ambassador Wells lacked accurate knowledge and had relied on “Western media ‘propaganda’” for her accusations. He called on the U.S. to “show your evidence, give me evidence” of specific cases of corruption related to the CPEC, and questioned whether Wells was taking potshots at the CPEC to score political points. Ambassador Yao challenged the U.S. to suit its actions to its words: “If there is any sincerity… [the U.S. should] come forward to invest in Pakistan. We [China] welcome U.S. investment in Pakistan.” (INP (Pakistan), November 22, 2019; VOA, November 22, 2019).

In addition to refocusing negative attention on the CPEC, Assistant Secretary of State Wells’ speech drew a reluctant Pakistan further into the tumultuous U.S.-China political rivalry. Pakistan faces a balance of payments crisis and a severely weakened currency, which has led it to grow increasingly dependent on economic ties with China. At the same time, the Pakistani leadership has navigated a complex and multifaceted historic security and political partnership with the U.S. If, as Ambassador Wells’ statement seems to imply, Pakistan’s engagement with China is seen to come at the expense of its bilateral relationship with the U.S. – or vice-versa – then Pakistan’s delicate power balancing diplomacy will soon become even more tenuous.

The Chinese Response

As mentioned, the sudden attack on the CPEC generated a rapid and strong reaction by the diplomats of the PRC. Ambassador Yao took the opportunity of responding to Ambassador Wells to also issue his own verbal attacks on U.S. foreign policy. Responding to the allegation that CPEC will be a debt trap for Pakistan, Jing said that China will never ask Pakistan to repay its loans if it is having financial difficulties. He alleged that the U.S.-controlled International Monetary Fund (IMF) would not give such a relaxation to Pakistan for its debts. He further stated that U.S. assistance had been unavailable in 2013 for Pakistan’s energy sector, but that China had provided needed investment through CPEC (Business Recorder, November 23). Image: PRC Foreign Ministry Spokesman Geng Shuang at a November 25, 2019 press briefing, in which he referred to the comments of Ambassador Wells as a “repetition of old slanders against China.” (Source: PRC Foreign Ministry)

Image: PRC Foreign Ministry Spokesman Geng Shuang at a November 25, 2019 press briefing, in which he referred to the comments of Ambassador Wells as a “repetition of old slanders against China.” (Source: PRC Foreign Ministry)

Image: PRC Foreign Ministry Spokesman Geng Shuang at a November 25, 2019 press briefing, in which he referred to the comments of Ambassador Wells as a “repetition of old slanders against China.” (Source: PRC Foreign Ministry)

Image: PRC Foreign Ministry Spokesman Geng Shuang at a November 25, 2019 press briefing, in which he referred to the comments of Ambassador Wells as a “repetition of old slanders against China.” (Source: PRC Foreign Ministry)

PRC Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Geng Shuang also responded to Ambassador Wells four days later in his official weekly press briefing. He described her comments as a “repetition of old slanders against China,” and claimed that U.S. officials had “fabricated [the] ‘debt issue’ with the true aim to disrupt CPEC development and sow discord in China-Pakistan relations with malicious calculations.” He said that if the U.S. government is really interested in assisting Pakistan, then it should “honor its commitments instead of always paying lip service and being the spoiler” (PRC Foreign Ministry, November 25).

These comments by a senior U.S. State Department official, and the harsh reaction by PRC officials, have put Pakistan in a tight spot. Since Pakistan is a partner of China in CPEC, it had to deny the claims made by Ambassador Wells. The Planning Commission of Pakistan—the body tasked with managing CPEC—responded to the assertions of Ambassador Wells by labeling them as incorrect assessments based on flawed analysis (Planning Commission of Pakistan, November 24). However, Pakistan’s ministers were careful not to directly criticize the United States on this matter. Asad Umer, Pakistan’s Minister in charge of CPEC, said that cooperation between Pakistan and China [in CPEC] is not directed against the United States. In the same press conference, he welcomed U.S. firms to invest in Pakistan, just as Chinese firms are making investments (Express Tribune, November 23). This measured statement by Umer reflects Pakistan’s policy of attempting, as far as is possible, to stay out of the China-U.S. rivalry.

CPEC: The Next Battleground for U.S.-China Rivalry?

CPEC has become engulfed in the U.S-China rivalry, and the comments of Ambassador Wells were the first shots fired. The United States has been generally critical of the BRI project of President Xi Jinping, but until recently CPEC was not directly criticized. Now, the equation seems to have changed. U.S. officials may have selected the current time to make this call because people in Pakistan are suffering economically: four years since its inception, CPEC has not proved to be the economic savior for Pakistan that some had expected, and many people in Pakistan have been disappointed. Hence, the time was opportune to highlight certain shady practices in CPEC so that it gets further attention among the Pakistani public. There is a group of people in Pakistan who have been warning the government against over-reliance on China, and the claims of Ambassador Wells provided further support for their arguments. [1]

Another way of analyzing the critique of Ambassador Wells is to interpret it as an attack on the debt-driven development model of BRI. Ever since the inception of BRI in 2013, the U.S. government has expressed concerns regarding the development model of BRI: it has been criticized as a non-sustainable debt-driven model, which helps China build influence in the host countries (China Brief, January 5, 2019).The U.S. government fears that through this model China will increase its strategic influence in Asia and Africa, and might replace the United States as the leading power in those regions. Therefore, Washington is repeatedly calling for a sustainable economic development strategy that can contribute to the development of under-developed countries—and allow them to maintain their sovereignty at the same time. Since CPEC is the flagship project of BRI, it has become the main target of U.S. criticism. [2]

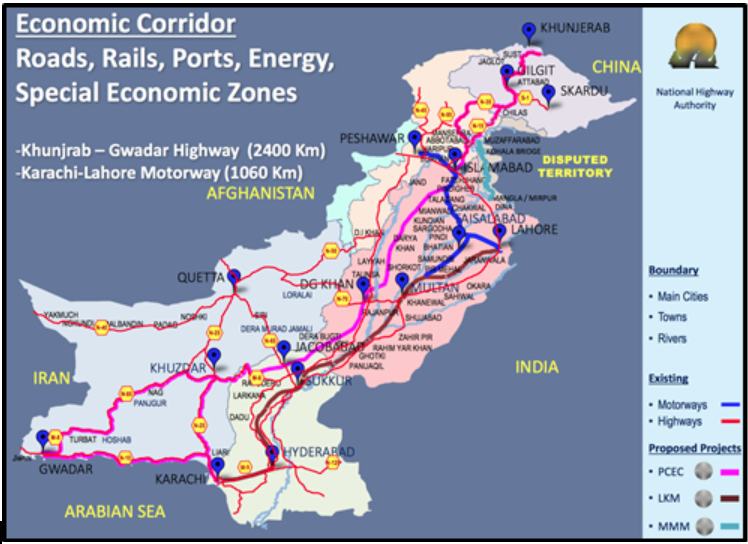

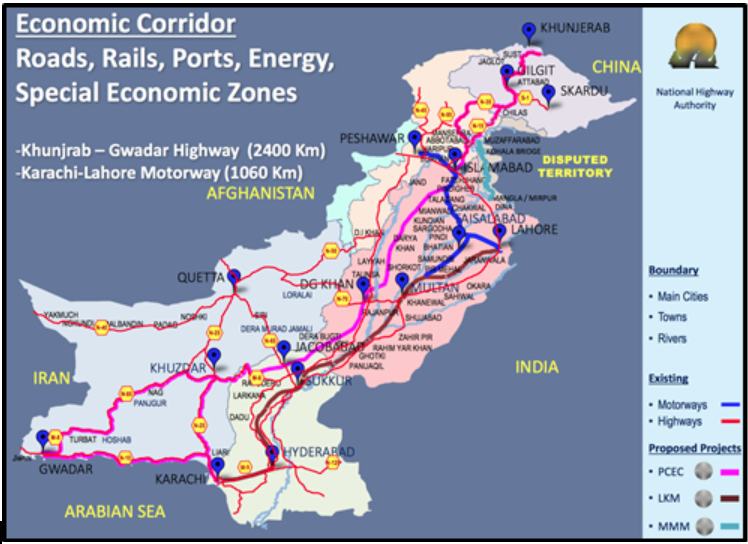

Pakistan still needs CPEC for its economic development. Even now, CPEC is the largest source of foreign development funding to Pakistan—notwithstanding the debate whether the funding represents beneficial foreign direct investment, or predatory loans. Pakistan’s government expects CPEC to build a large railway artery connecting Karachi in the south to Peshawar in the north. It also hopes to develop the port of Gwadar into a major commercial hub in the near future (China Brief, July 31, 2015; China Brief, February 15, 2019; China Brief, December 10, 2019). In addition, Pakistan is also relying on CPEC to generate jobs for its ailing economy. Therefore, CPEC continues to be a dominating factor in the economic paradigm of Pakistan—and many political and business leaders support it, irrespective of any criticism launched against it by the United States. Image: A map of the proposed “China-Pakistan Economic Corridor” of transportation infrastructure projects. (Source: Pakistan National Highway Authority)

Image: A map of the proposed “China-Pakistan Economic Corridor” of transportation infrastructure projects. (Source: Pakistan National Highway Authority)

Image: A map of the proposed “China-Pakistan Economic Corridor” of transportation infrastructure projects. (Source: Pakistan National Highway Authority)

Image: A map of the proposed “China-Pakistan Economic Corridor” of transportation infrastructure projects. (Source: Pakistan National Highway Authority)

Pakistan also needs the support of the United States. There have been strains in the relations of both countries in the last few years, but things changed after Prime Minister Imran Khan paid a visit to the White House in July 2019. The U.S. government has indicated that it would give Pakistan greater help in the Afghan peace process. More recently, the U.S. approved the participation of Pakistan in the International Military Education and Training Program (Dawn, December 20). This indicates that the U.S. has mended fences with Islamabad for the sake of its interests in Afghanistan. At a time when Pakistan has succeeded in rapprochement with the United States, the last thing it wants is to alienate Washington over the CPEC.

The Implications for Pakistan

The first implication for Pakistan is that it risks drawing the ire of Beijing on this matter. Pakistan responded to the comments on Ambassador Wells—but it was a muted response, similar to the way that Pakistan responds to similar criticism from India. Beijing will likely feel that Pakistan is trying to appease both China and the United States, while China is the only one pumping money into Pakistan. Therefore, Pakistan will be pressed by China to take sides—at least on the issue of CPEC—and to clearly denounce the U.S. government on this matter. Pakistan will find this difficult to do given its recent restoration of good relations with Washington. China could take steps of its own to pressure Pakistan, such as not extending non-CPEC loans if Pakistan needs them in the near future.

These provocative comments from Ambassador Wells have also increased the internal pressure on the government of Pakistan vis-à-vis CPEC. Ambassador Wells asked Pakistanis to ask tough questions on CPEC—a process that had already started. Her criticisms are being used as a proof of flaws in CPEC by internal critics in Pakistan, who have increased their demands to make CPEC agreements public and to make the decision-making processes surrounding these mega projects more transparent. Therefore, it will be a challenge for Islamabad to control the internal criticism on CPEC, because China reportedly does not want CPEC agreements and the discussions surrounding them to be made public.

If Pakistan and China want to prove Ambassador Wells wrong, they will have to show successful results for CPEC. This will be hard to achieve, because so far the performance of CPEC has been less than satisfactory. Therefore, it is unlikely that CPEC can deliver any miracle in the recent future: it is not going to control inflation, fix unemployment, or resolve the foreign currency exchange crisis in Pakistan anytime soon. In such a case, the criticism of CPEC becomes more credible and harder for Pakistan and China to defend. Therefore, both Islamabad and Beijing want CPEC to succeed—and this will put immense pressure on those in charge of CPEC projects to deliver tangible benefits.

Ambassador Wells’s meticulous attack on the CPEC has come at a bad time for Pakistan, which can’t afford to be further entangled in the wider U.S.-China rivalry. Pakistan would prefer to maintain a cautious approach in order to appease both powers. However, this is not going to work: China expects Pakistan’s unequivocal support on the CPEC, while U.S. criticism on the CPEC will not end until all of the program’s shortcomings have been addressed. This leaves the Pakistani leadership in the uncomfortable position of being caught between a rock and an increasingly hard place.

Adnan Aamir is a journalist and researcher based in Pakistan. He has written extensively on the Belt and Road Initiative for Nikkei Asian Review, Financial Times, South China Morning Post, Asia Times, the Lowy Institute, and CSIS, among others. He was a Chevening South Asian Journalism Fellow 2018 at the University of Westminster, London. Follow him on twitter at @iAdnanAamir

No comments:

Post a Comment