by Mary K. Feeney

All of the 2019 Nobel Prizes in science were awarded to men.

That’s a return to business as usual, after biochemical engineer Frances Arnold won in 2018, for chemistry, and Donna Strickland received the 2018 Nobel Prize in physics.

Strickland was only the third female physicist to get a Nobel, following Marie Curie in 1903 and Maria Goeppert-Mayer 60 years later. When asked how that felt, she noted that at first it was surprising to realize so few women had won the award: “But, I mean, I do live in a world of mostly men, so seeing mostly men doesn’t really ever surprise me either."

After 117 years, a third woman won a physics Nobel. Alexander Mahmoud, © Nobel Media AB 2018, Author provided (No reuse)

The rarity of female Nobel laureates raises questions about women’s exclusion from education and careers in science. Female researchers have come a long way over the past century. But there’s overwhelming evidence that women remain underrepresented in the STEM fields of science, technology, engineering and math.

Studies have shown those who persist in these careers face explicit and implicit barriers to advancement. Bias is most intense in fields that are predominantly male, where women lack a critical mass of representation and are often viewed as tokens or outsiders.

When women achieve at the highest levels of sports, politics, medicine and science, they serve as role models for everyone - especially for girls and other women.

As things are getting better in terms of equal representation, what still holds women back in the lab, in leadership and as award winners?

Good news at the start of the pipeline

Traditional stereotypes hold that women “don’t like math" and “aren’t good at science." Both men and women report these viewpoints, but researchers have empirically disputed them. Studies show that girls and women avoid STEM education not because of cognitive inability, but because of early exposure and experience with STEM, educational policy, cultural context, stereotypes and a lack of exposure to role models.

For the past several decades, efforts to improve the representation of women in STEM fields have focused on countering these stereotypes with educational reforms and individual programs that can increase the number of girls entering and staying in what’s been called the STEM pipeline - the path from K-12 to college to postgraduate training.

These approaches are working. Women are increasingly likely to express an interest in STEM careers and pursue STEM majors in college. Women now make up half or more of workers in psychology and social sciences and are increasingly represented in the scientific workforce, though computer and mathematical sciences are an exception.

According to the American Institute of Physics, women earn about 20% of bachelor’s degrees and 18% of Ph.D.s in physics, an increase from 1975 when women earned 10% of bachelor’s degrees and 5% of Ph.D.s in physics.

More women are graduating with STEM Ph.D.s and earning faculty positions. But they encounter glass cliffs and ceilings as they advance through their academic careers.

What’s not working for women

Women face a number of structural and institutional barriers in academic STEM careers.

In addition to issues related to the gender pay gap, the structure of academic science often makes it difficult for women to get ahead in the workplace and to balance work and life commitments. Bench science can require years of dedicated time in a laboratory. The strictures of the tenure-track process can make maintaining work-life balance, responding to family obligations and having children or taking family leave difficult, if not impossible.

Additionally, working in male-dominated workplaces can leave women feeling isolated, perceived as tokens and susceptible to harassment. Women often are excluded from networking opportunities and social events, left to feel they’re outside the culture of the lab, the academic department and the field.

When women lack a critical mass in a workplace - making up about 15% or more of workers - they are less empowered to advocate for themselves and more likely to be perceived as a minority group and an exception. When in this minority position, women are more likely to be pressured to take on extra service as tokens on committees or mentors to female graduate students.

With fewer female colleagues, women are less likely to build relationships with female collaborators and support and advice networks. This isolation can be exacerbated when women are unable to participate in work events or attend conferences because of family or child care responsibilities and an inability to use research funds to reimburse child care.

Universities, professional associations and federal funders have worked to address a variety of these structural barriers. Efforts include creating family-friendly policies, increasing transparency in salary reporting, enforcing Title IX protections, providing mentoring and support programs for women scientists, protecting research time for women scientists and targeting women for hiring, research support and advancement. These programs have mixed results.

For example, research indicates that family-friendly policies such as leave and onsite child care can exacerbate gender inequity, resulting in increased research productivity for men and increased teaching and service obligations for women.

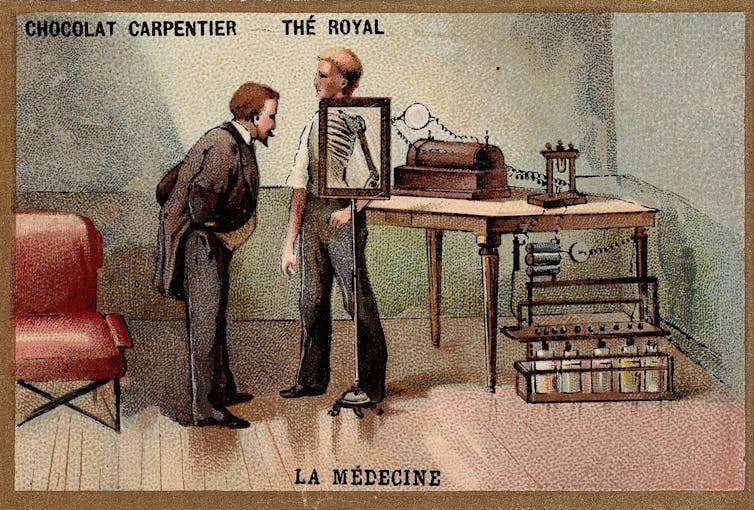

People haven’t really updated their mental images of what a scientist looks like since Wilhelm Roentgen won the first physics Nobel in 1901. Wellcome Collection, CC BY

Implicit biases about who does science

All of us - the general public, the media, university employees, students and professors - have ideas of what a scientist and a Nobel Prize winner looks like. That image is predominantly male, white and older - which makes sense given 97% of the science Nobel Prize winners have been men.

This is an example of an implicit bias: one of the unconscious, involuntary, natural, unavoidable assumptions that all of us - men and women - form about the world. People make decisions based on subconscious assumptions, preferences and stereotypes - sometimes even when they are counter to their explicitly held beliefs.

Research shows that an implicit bias against women as experts and academic scientists is pervasive. It manifests itself by valuing, acknowledging and rewarding men’s scholarship over women’s scholarship.

Implicit bias can work against women’s hiring, advancement and recognition of their work. For instance, women seeking academic jobs are more likely to be viewed and judged based on personal information and physical appearance. Letters of recommendation for women are more likely to raise doubts and use language that results in negative career outcomes.

Implicit bias can affect women’s ability to publish research findings and gain recognition for that work. Men cite their own papers 56% more than women do. Known as the “Matilda Effect," there is a gender gap in recognition, award-winning and citations.

Women’s research is less likely to be cited by others, and their ideas are more likely to be attributed to men. Women’s solo-authored research takes twice as long to move through the review process. Women are underrepresented in journal editorships, as senior scholars and lead authors and as peer reviewers. This marginalization in research gatekeeping positions works against the promotion of women’s research.

When a woman becomes a world-class scientist, implicit bias works against the likelihood that she will be invited as a keynote or guest speaker to share her research findings, thus lowering her visibility in the field and the likelihood that she will be nominated for awards. This gender imbalance is notable in how infrequently women experts are quoted in news stories on most topics.

Donna Strickland, outside her lab at the University of Waterloo, won her Nobel in 2018 as an associate professor. Reuters/Peter Power

Women scientists are afforded less of the respect and recognition that should come with their accomplishments. Research shows that when people talk about male scientists and experts, they’re more likely to use their surnames and more likely to refer to women by their first names.

Why does this matter? Because experiments show that individuals referred to by their surnames are more likely to be viewed as famous and eminent. In fact, one study found that calling scientists by their last names led people to consider them 14% more deserving of a National Science Foundation career award.

Seeing mostly men has been the history of science. Addressing structural and implicit bias in STEM will hopefully prevent another half-century wait before the next woman is acknowledged with a Nobel Prize for her contribution to physics. I look forward to the day when a woman receiving the most prestigious award in science is newsworthy only for her science and not her gender.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on Oct. 5, 2018.

Mary K. Feeney, Professor and Lincoln Professor of Ethics in Public Affairs and Associate Director of the Center for Science, Technology and Environmental Policy Studies, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment