By SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR

Russian and Chinese jammers could cripple US radio, radar, and GPS. The Pentagon's still wrestling with who should fix that, let alone how.

Russian and Chinese jammers could cripple US radio, radar, and GPS. The Pentagon's still wrestling with who should fix that, let alone how.

ARLINGTON: Five years ago, Pentagon research & engineering chief Alan Shaffer warned that “we have lost the electromagnetic spectrum.” Today, after the Russians have jammed US and allied radio, radar, and GPS from Syria to Ukraine to Norway, are we doing better?

“I’m going to characterize it this way….I want to be careful,” Maj. Gen. Lance Landrum told reporters at an Association of Old Crows roundtable this morning: “I can very firmly say we’re challenged in the electromagnetic spectrum.”

Landrum, an Air Force fighter pilot on the Joint Staff, leads the group Congress ordered the Pentagon to create, the Electromagnetic Spectrum Operations Cross Functional Team. (Officially, the Vice-Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Gen. John Hyten, is the task force’s director, but Landrum runs things day to day as deputy director).

The team is tiny – just 13 government personnel, all borrowed from other organizations, plus some contractors – but it represents 11 organizations across the Defense Department. That’s all four armed services, the joint staff, the Pentagon CIO, the undersecretariats for acquisition, research, and intelligence, Cyber Command, and Strategic Command, which historically had responsibility for electronic warfare but very little authority or funding to do anything about it.

The problem is that literally everyone in the Defense Department – for that matter, everyone reading this article – depends on the spectrum to do their job. Who doesn’t need to be at the table, when the spectrum is essential to every walkie-talkie and cellphone, to every radar, radio, jamming pod, and GPS on every plane, helicopter, ship, tank, and truck? Who gets to be in charge of something that affects everybody?

“I think that’s the big question,” Landrum said to a ripple of nervous laughter around the table. “We need improvement on how we have unity of effort…and that’s why we’re focused on governance.

“We have great offices and great people in the department all trying to do the right thing in different areas,” he went on. “Who is the single accountable, empowered, and authorized person that brings all this together? That’s where we see an opportunity for improvement, and that’s why we’re having these discussions right now that are predecisional,” he said. “We need to put some options on the table.”

The CFT believes the Defense Department needs an “organization that champions EMSO and has the level of rank and visibility [to work] with the highest levels of our department, like the Deputy Secretary of Defense and the Secretary,” Landrum said.

“How is that organization resourced, how is that organization staffed, etc.? We don’t have any conclusions right now,” he admitted. “However, we are moving forward with ideas and we are working through the offices and our chains to present some of those ideas here in the future.”

“Governance is our No. 1 line of effort,” added the task force chief of staff, Navy Cdr. Scott Oliver. “Those are some very tough conversations that we are having within the department about who is responsible and accountable.”

US Air Force F-35A

Jammers, Analysts, & Coders

While the Defense Department is still debating organization, it is taking action to shore up the spectrum. That includes an array of new equipment across the services, most notably

The Navy’s Next Generation Jammer for its EA-18G Growler jet and the Surface Electronic Warfare Improvement Program (SEWIP) for Navy warships;

The Army’s ground-based jammer, the Terrestrial Layer System (TLS), and the drone-borne Multi-Function Electronic Warfare (MFEW) Air program;

The Air Force’s upgrade of its Compass Call EW aircraft from the aging EC-130 turboprop to the EC-37B jet; and

The highly classified but allegedly awesome cyber/electronic warfare capabilities of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter.

Landrum and the Cross Functional Team, for their part, are working on cross-cutting issues (hence the name) that affect all four services and the Intelligence Community.

For example, every combat aircraft has electronic protection systems to detect and jam incoming anti-aircraft missiles. Every time a potential adversary upgrades their radar, all those countermeasures need to know how to recognize the new threat. But the laborious process the Defense Department uses to do this – from detecting enemy radar signals, to analyzing them, to issuing updated threat data across its fleets of aircraft – struggles to keep up with rapid advances in enemy electronics. While the F-35 program’s struggles with its mission data files have been the best publicized problems of this sort, it’s an issue across the force.

“What’s the process by which we characterize and validate that information?” Landrum said. How does it move from the collectors of the intelligence to the analysts to the program managers and coders who have to make specific updates to specific weapons systems?

“From the moment a new signal is detected until the time it is reprogrammed into a weapon or platform… that’s the enterprise process that we’re looking at, to streamline that and make it go a lot quicker,” said Oliver.

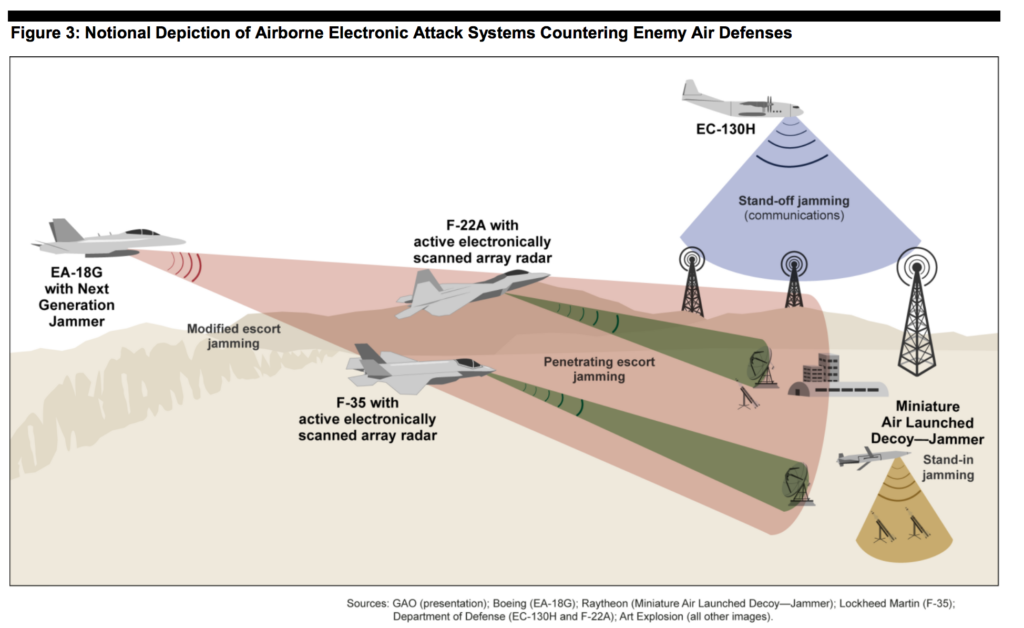

While older aircraft like the EA-18G and EC-130H jam enemy systems from a distance, stealthy F-22s and F-35s can slip through air defenses to conduct electronic warfare at close range.

“The work that we envision will inform not just the F-35 process but also all the other weapon systems that need to understand the characterization of signals,” Landrum said. The ultimate goal is to have at least some of this detection-analysis-countermeasure cycle happen nigh-instantaneously on individual aircraft and vehicles, so-called cognitive electronic warfare using artificial intelligence to figure out what’s happening and how to respond faster than any human mind.

The Cross Functional Team is not only looking at technology, but at the human dimension as well. “We’re a couple of months into what we anticipate to be a year-long work force study,” Landrum said. The goal is to identify everyone across the Defense Department – uniformed military and civilian – who works on some aspect of the spectrum – from allocation frequency and bandwidth in conjunction with the FAA, to jamming enemy systems in combat – and figure out better ways to develop them as professionals from recruitment to retirement.

Army Tactical Electronic Warfare System (TEWS) at the National Training Center on Fort Irwin, California.

Command & Management

The military is already moving more experts into selected theater commands. European Command (which deals with Russia), Central Command (ditto), Indo-Pacific Command (China), and (surprisingly, given its second-string status) Africa Command are all building up what Landrum called “nascent” Joint Electromagnetic Spectrum Operations Cells. Different commands are experimenting with different ways to organize their JEMSOCs, which in turn reach back to the Joint Electromagnetic Warfare Center (JEWC) in San Antonio for heavy-duty analysis.

For the first two years, the cells will rely on support from contractors, Oliver said, but there’s a formal Joint Manpower Validation Study underway to get them completely staffed by Defense Department personnel.

“They are intended to be a ground zero of subject matter expertise for the commander,” Landrum said. “A commander and a commander’s staff need to have an understanding and a view of the electromagnetic environment in order to plan… and to understand the risks associated with operational decisions.”

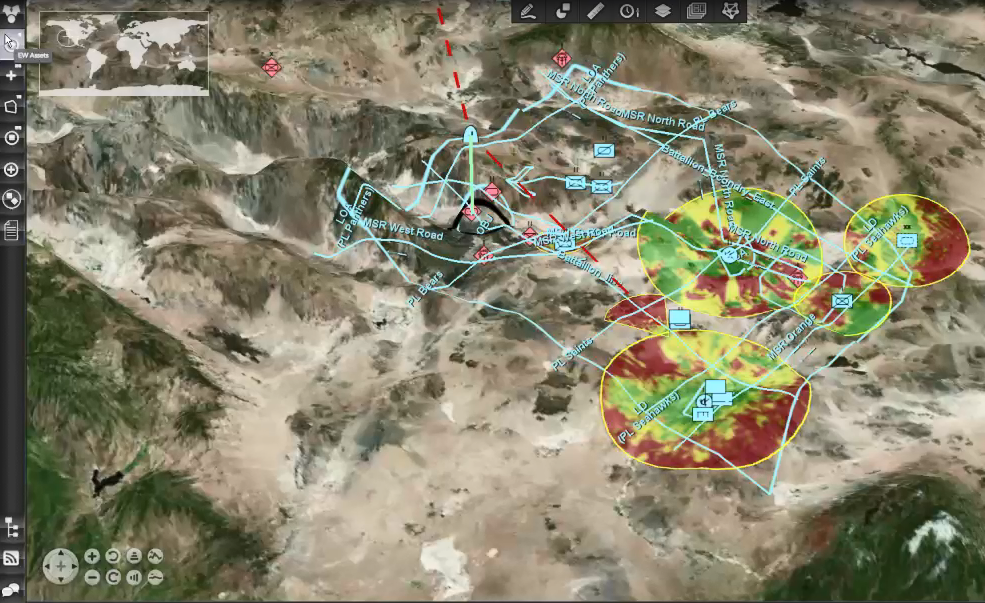

Screenshot from an early version of Raytheon’s Electronic Warfare Planning & Management Tool

Planning, however, requires not just expertise but data. Today, spectrum managers and electronic warriors often rely on Excel tables and sticky notes to track the different systems on the battlefield and what frequencies they’re using. What the military really wants is a live display that maps out where emitters are and what forces – friendly and enemy – they can affect, in real time, so commanders can see the situation at a glance and make quick, informed decisions.

So, Landrum said, “one area that we are focused on is electromagnetic battle management, EMBM, [a] picture of the electromagnetic operating environment for our commanders.”

So, Landrum said, “one area that we are focused on is electromagnetic battle management, EMBM, [a] picture of the electromagnetic operating environment for our commanders.”

A soldier gets help with VMAX portable jamming system

“We feel it needs improving,” he said frankly. Just getting a clear picture of where different friendly emitters are and how they might interfere with each other – let alone enemy and neutral ones – is a major challenge that will take “at least a couple of years,” he said.

Meanwhile the Cross Functional Team is working on a comprehensive electromagnetic spectrum operations strategy for the department – currently there are separate strategies for electronic warfare and spectrum management, the latter six years old – and on regular Section 1053 reports to Congress every six months.

One thing Landrum and the team are not working on: getting the electromagnetic spectrum formally elevated to the status of a doctrinally recognized “domain,” co-equal to land, air, sea, space, and cyberspace. The spectrum touches on all those domains and connects them, Landrum said, but whether it’s a domain in its own right is a more tangled question than he wants to wrestle with right now.

“The domain thing comes up all the time,” he said. “We would have to ask: for what purpose do we want to declare the EMS as a domain…. Does that or does that not help us? Because there can be arguments in both ways.”

“The electromagnetic spectrum is a physical maneuver space, it’s a physical battlespace that is ubiquitous, it’s present at all times,” Landrum said, “and our air, land, sea, and space forces need to win in the electromagnetic spectrum in order for them to win in the air, land, sea, and space.” (This synergy of effort is known as Multi-Domain Operations).

“It is that important,” he said, adding with a laugh: “How’s that for painful wordsmithing?”

No comments:

Post a Comment