The MOD’s Defence and Security Accelerator (DASA) was set up in 2016 to "to help UK military and security users access innovative ideas, equipment and services more quickly".

The MOD’s Defence and Security Accelerator (DASA) was set up in 2016 to "to help UK military and security users access innovative ideas, equipment and services more quickly".

As part of their strategy, DASA established Open Calls for Innovation and a series of themed competitions, which are designed to encourage the private sector, and specifically SMEs, start-ups and non-traditional defence companies, to be part of the MOD’s problem-solving eco-system and submit ideas to tackle some of the UK’s most pressing challenges.

One such competition, launched earlier this year, focuses on Countering Hostile Drones. DASA received 90 bids from industry, and on 5 November they announced £2 million worth of contracts to 18 companies to develop "robust and cost-effective next-generation solutions to the risks posed by hostile UAS”.

To find out more about the competition, Defence iQ spoke to Ben Cook, founder of Airspeed Electronics, one of the SMEs involved in the competition. We discuss DASA competitions, the difference between SMEs and primes when it comes to innovating, and the wider benefits SMEs offer the defence community.

A threat to critical national infrastructure: the emergence of drones. (Shutterstock)

Could you tell me about the history of Airspeed Electronics and, specifically, the design, development, and delivery of MANTIS? What kind of capability does it offer to the military?

Airspeed was incorporated in 2018. I created the company to provide agile R&D services to larger process-oriented engineering organisations.

Our Counter-Drone offering is a sensor system called MANTIS (MAchine learNing acousTIc Surveillance). The MANTIS concept employs a system of distributed intelligent acoustic sensors, which use Artificial Intelligence algorithms to detect and track UAS purely by their acoustic signature.

Whilst there are range limitations with acoustic sensors, MANTIS overcomes these by physically distributing many sensor units, which are connected to a central server via a radio datalink. In this way, MANTIS would be able to provide wide-area coverage within a radius of several kilometres of a central hub.

MANTIS offers a standalone surveillance capability, however it could also be integrated with more complex layered counter-UAS systems. For example, an acoustic ‘early-warning’ sensor network has potential to augment the capabilities of traditional RADAR systems in tracking drones flying at very low altitude, or through ‘urban canyons’. By extension, a combined multi-mode system employing acoustic, RF and electro-optic cameras has formidable potential in the counter-UAS space.

DASA recently awarded Airspeed Electronics, along with a number of other SMEs and start-ups, with funding Under Phase I of its Countering Hostile Drones competition. This is another great example of how defence is extending its engagement to innovators outside of the traditional defence industrial base, both in terms of funding to support proof of concept development, and open competitions which are more user-oriented.

Could you talk about your experience working through the DASA/MOD framework? Did you confront any significant challenges i.e. technical, legal or perhaps need support with particular aspects of the competition?

We are in the early stages of this DASA project, so I can’t comment on the end-to-end DASA experience. So far it has been a positive. If a proposal is selected for funding, the supplier maintains full ownership of the project Intellectual Property. Projects are also 100% funded by MoD, so unlike some other funding initiatives, additional investment is not usually required. It's also a fantastic opportunity to build industrial partnerships, so, fFrom a business perspective, there’s not a lot to dislike.

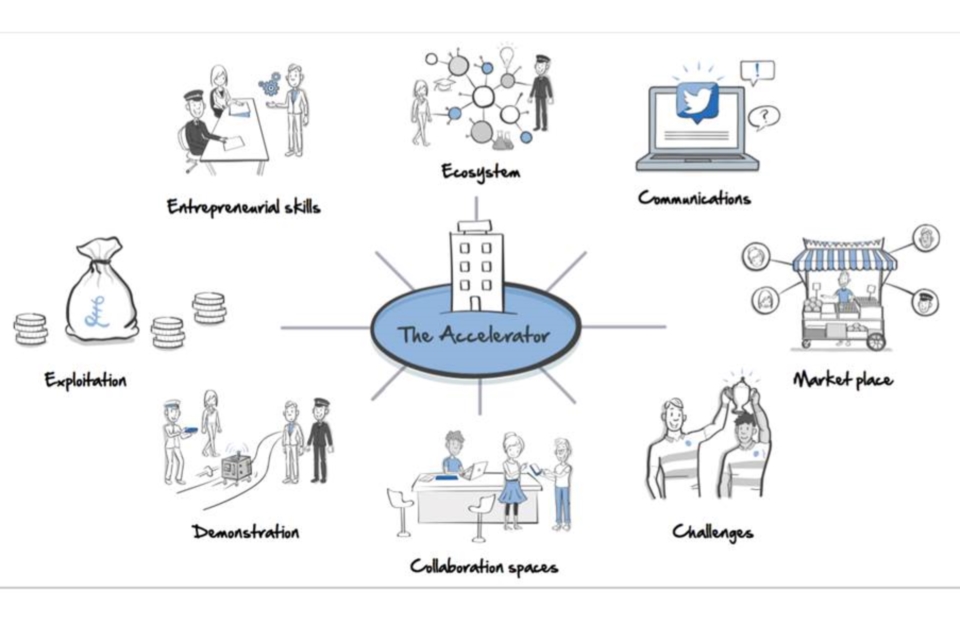

The DASA concept outlined in 2016. Two years later, the organisation was set up. UK MOD.

In addition to established defence suppliers, an increasing number of SMEs and startups are appearing on the back-catalogue of projects funded by DASA. To me, this indicates the UK’s desire to build diversity in the Defence and Security supply-chain, by promoting small businesses, universities and other institutions.

DASA also runs themed competitions, in which technology concepts are ‘pulled’ from the supply chain, and an ‘open call’, where suppliers can instead ‘push’ concepts which they think might be of value to UK Defence and Security. The level of competition is high, so it pays for the supplier to invest time in the preparation of the proposal. The requirements for proposals cover many aspects of technical and commercial viability, so writing the proposal is a good test of the concept.

You’ve had experience working for major defence contractors in the past, and made significant contributions to major platform programmes. How does your experience working on these projects compare to what you do now? Do you have any feedback to share about how the defence community (prime contractors and/or government) could further improve their engagement with SMEs?

What many SMEs and start-ups may lack in resources, they make up for in speed and agility. I find that I am able to progress projects much faster than I could when working for a ‘typical’ defence company. There are a number of reasons for this. Firstly, defence primes are required to follow complex quality processes, which are essential in ensuring product reliability and quality in their production standards. Secondly, these are usually large and complex organisations which, by necessity, attract and promote risk-averse managers. Their attitudes become a cultural norm within the business. These are the perfect conditions for building more of the same thing to a high standard, but if you’re trying to invent something new which might not work, it’s not always a sympathetic environment.

Predictably, there is a lot of talk about the importance of innovation from defence company directors, but my experience of attempting to innovate inside big defence companies was invariably like wading through treacle. It’s very difficult; regulated industries really dislike disruption.

A well-trodden workaround employed by many defence firms is to create an internal business unit that behaves like a small, lightweight R&D company. Lockheed Martin’s ‘Skunkworks’ model has been emulated by many, with varying degrees of success. Some are ineffective because, over time, the culture and practices of the parent company bleed across into the R&D organisation by osmosis.

I believe that to establish effective R&D teams requires a degree of isolation from conventional production operations and the people who run them. This can of course be achieved under the same roof. Alternatively, one could create an independent R&D company. Last year I founded Airspeed Electronics with this business model in mind.

I have put my money (literally) behind the idea that large defence organisations and governments will in future become increasingly reliant on SME’s, academic institutions and freelance innovators as a source of technology innovation and R&D activity. I believe they will be left with no other choice. Whilst the prime contractors continue to coalesce into even larger, increasingly unwieldy multi-national business structures, the competitive need for rapid technology development is accelerating at a remarkable pace.

It’s easy to forget that the first commercial quadrotor ‘drone’ was introduced to the market as recently as 2010. Today, less than a decade later, the burgeoning drone business is already a global, multi-billion dollar industry. Today’s commercial drones should no longer be thought of as toys. They are sophisticated air platforms being pressed into service for critical industrial, humanitarian and military roles.

This disruption has happened precisely because a handful of agile and energetic SME’s, inventors and hobbyists had the imagination to experiment with new types of flying machines by re-purposing sensor, microprocessor and battery technology developed for the mobile phone industry. I see no evidence that the established aerospace companies were involved in this. You can start to see traditional industrial lines being blurred in the space-launch sector too.

The proof of concepts under the Counter Hostile Drones programme will be demonstrated in mid-2020. What are your priorities leading up to that, and, outside of the competition, what are your ambitions for Airspeed Electronics? Are there other opportunities in the defence and security sector which are of interest?

My immediate priority is to service the plan agreed with MoD to deliver a demonstration system for MANTIS. I have an incremental proving plan which concludes in July 2020. Secondly, I’d like to raise the profile of my company and our capabilities inside the wider defence community. Within one to two years I aspire to scale-up the business in order to take on larger projects.

I am interested in using my company to develop new technology in autonomous systems, AI, unmanned aircraft, mobile robotics and advanced sensing systems. I have some ideas for new technologies which could aid landmine clearance for example, and strong views about improving the integrity of commercial drone systems to facilitate operation in commercial airspace.

I have also identified some overlap between the requirements applied to military systems design and those emerging in other industrial sectors. For example, drive-by-wire cars with high levels of autonomy require safety-critical aerospace grade electronic systems. The skill-set required to develop these types of systems is not present in great numbers in the automotive industry because their safety-case has always assumed man-in-the-loop control with very low levels of autonomy.

In the defence sector, we’ve been designing autonomous safety critical systems for UAVs and guided weapons for decades. I predict that we will start to see greater levels of cross-fertilization between these two traditionally stove-piped industrial sectors.

No comments:

Post a Comment